Hearing National Defense Authorization Act For

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Ibew Local Union 26 2020 Election Endorsements

IBEW LOCAL UNION 26 2020 ELECTION ENDORSEMENTS The Local 26 staff and the many activist members of our Union have met, interviewed, and questioned nu- merous candidates on both sides of the ballot. We have offered an olive branch to all candidates, in all parties. In some election races, neither candidate received our support. Our endorsements went only to those candidates who best served the members of Local 26, our families, and our future. Please use this endorsement list as a guide when casting your ballot. If you have any questions about registering, voting, ballot initiatives, or candi- dates please contact Tom Clark at 301-459-2900 Ext. 8804 or [email protected] US President/Vice President Joe Biden and Kamala Harris Maryland US House District 2: Dutch Ruppersberger US House District 3: John Sarbanes US House District 4: Anthony Brown US House District 5: Steny Hoyer US House District 6: David Trone US House District 7: Kweisi Mfume US House District 8: Jamie Raskin Question 1: YES Montgomery County Question A: For Question B: Against District of Columbia US House: Eleanor Holmes Norton DC Council at-large: Ed Lazere DC Council at-large: Robert White DC Council Ward 2: Brooke Pinto DC Council Ward 4: Janeese Lewis George DC Council Ward 7: Vincent Gray DC Council Ward 8: Trayon “Ward Eight” White Virginia US House District 1: Qasim Rashid US House District 2: Elaine Luria US House District 3: Bobby Scott US House District 4: Donald McEachin US House District 5: Dr. Cameron Webb US House District 7: Abigail Spanberger US House District 8: Don Beyer US House District 10: Jennifer Wexton US House District 11: Gerald Connolly Arlington Co Board Supervisors: Libby Garvey House of Delegates District 29: Irina Khanin Frederick County Board of Supervisors, Shawnee District: Richard Kennedy Luray Town Council: Leah Pence. -

Congressional Directory MARYLAND

124 Congressional Directory MARYLAND Office Listings—Continued Chief of Staff.—Karen Robb. Legislative Director.—Sarah Schenning. Communications Director.—Bridgett Frey. State Director.—Joan Kleinman (301) 545–1500 111 Rockville Pike, Suite 960, Rockville, MD 20850 .............................................................. (301) 545–1500 32 West Washington Street, Suite 203, Hagerstown, MD 21740 ............................................. (301) 797–2826 REPRESENTATIVES FIRST DISTRICT ANDY HARRIS, Republican, of Cockeysville, MD; born in Brooklyn, NY, January 25, 1957; education: B.S., Johns Hopkins University, Baltimore, MD, 1977; M.D., Johns Hopkins Univer- sity, Baltimore, 1980; M.H.S., Johns Hopkins University, 1995; professional: anesthesiologist, as an associate professor of anesthesiology and critical care medicine; member of the Maryland State Senate, 1998–2010; Minority Whip, Maryland State Senate; military: Commander, Johns Hopkins Medical Naval Reserve Primus Unit P0605C; religion: Catholic; widowed; five chil- dren; four grandchildren; committees: Appropriations; elected to the 112th Congress on Novem- ber 2, 2010; reelected to each succeeding Congress. Office Listings http://harris.house.gov 1533 Longworth House Office Building, Washington, DC 20515 ........................................... (202) 225–5311 Chief of Staff.—John Dutton. FAX: 225–0254 Legislative Director.—Tim Daniels. Press Secretary.—Jacque Clark. Scheduler.—Charlotte Heyworth. 100 Olde Point Village, Suite 101, Chester, MD 21619 .......................................................... -

August 10, 2021 the Honorable Nancy Pelosi the Honorable Steny

August 10, 2021 The Honorable Nancy Pelosi The Honorable Steny Hoyer Speaker Majority Leader U.S. House of Representatives U.S. House of Representatives Washington, D.C. 20515 Washington, D.C. 20515 Dear Speaker Pelosi and Leader Hoyer, As we advance legislation to rebuild and renew America’s infrastructure, we encourage you to continue your commitment to combating the climate crisis by including critical clean energy, energy efficiency, and clean transportation tax incentives in the upcoming infrastructure package. These incentives will play a critical role in America’s economic recovery, alleviate some of the pollution impacts that have been borne by disadvantaged communities, and help the country build back better and cleaner. The clean energy sector was projected to add 175,000 jobs in 2020 but the COVID-19 pandemic upended the industry and roughly 300,000 clean energy workers were still out of work in the beginning of 2021.1 Clean energy, energy efficiency, and clean transportation tax incentives are an important part of bringing these workers back. It is critical that these policies support strong labor standards and domestic manufacturing. The importance of clean energy tax policy is made even more apparent and urgent with record- high temperatures in the Pacific Northwest, unprecedented drought across the West, and the impacts of tropical storms felt up and down the East Coast. We ask that the infrastructure package prioritize inclusion of a stable, predictable, and long-term tax platform that: Provides long-term extensions and expansions to the Production Tax Credit and Investment Tax Credit to meet President Biden’s goal of a carbon pollution-free power sector by 2035; Extends and modernizes tax incentives for commercial and residential energy efficiency improvements and residential electrification; Extends and modifies incentives for clean transportation options and alternative fuel infrastructure; and Supports domestic clean energy, energy efficiency, and clean transportation manufacturing. -

JOIN the Congressional Dietary Supplement Caucus

JOIN the Congressional Dietary Supplement Caucus The 116th Congressional Dietary Supplement Caucus (DSC) is a bipartisan forum for the exchange of ideas and information on dietary supplements in the U.S. House of Representatives and the Senate. Educational briefings are held throughout the year, with nationally recognized authors, speakers and authorities on nutrition, health and wellness brought in to expound on health models and provide tips and insights for better health and wellness, including the use of dietary supplements. With more than 170 million Americans taking dietary supplements annually, these briefings are designed to educate and provide more information to members of Congress and their staff about legislative and regulatory issues associated with dietary supplements. Dietary Supplement Caucus Members U.S. Senate: Rep. Brett Guthrie (KY-02) Sen. Marsha Blackburn, Tennessee Rep. Andy Harris (MD-01) Sen. John Boozman, Arkansas Rep. Bill Huizenga (MI-02) Sen. Tom Cotton, Arkansas Rep. Derek Kilmer (WA-06) Sen. Tammy Duckworth, Illinois Rep. Ron Kind (WI-03) Sen. Martin Heinrich, New Mexico Rep. Adam Kinzinger (IL-16) Sen. Mike Lee, Utah Rep. Raja Krishnamoorthi (IL-08) Sen. Tim Scott, South Carolina Rep. Ann McLane Kuster (NH-02) Sen. Kyrsten Sinema, Arizona Rep. Ted Lieu (CA-33) Rep. Ben Ray Luján (NM-03) U.S. House of Representatives: Rep. John Moolenaar (MI-04) Rep. Mark Amodei (NV-02) Rep. Alex Mooney (WV-02) Rep. Jack Bergman (MI-01) Rep. Ralph Norman (SC-05) Rep. Rob Bishop (UT-01) Rep. Frank Pallone (NJ-06) Rep. Anthony Brindisi (NY-22) Rep. Mike Rogers (AL-03) Rep. Julia Brownley (CA-26) Rep. -

1 April 2, 2020 the Honorable Nancy Pelosi Speaker, U.S. House Of

April 2, 2020 The Honorable Nancy Pelosi Speaker, U.S. House of Representatives H-232, United States Capitol Washington, DC 20515 Dear Speaker Pelosi: We are grateful for your tireless work to address the needs of all Americans struggling during the COVID-19 pandemic, and for your understanding of the tremendous burdens that have been borne by localities as they work to respond to this crisis and keep their populations safe. However, we are concerned that the COVID-19 relief packages considered thus far have not provided direct funding to stabilize smaller counties, cities, and towns—specifically, those with populations under 500,000. As such, we urge you to include direct stabilization funding to such localities in the next COVID-19 response bill, or to lower the threshold for direct funding through the Coronavirus Relief Fund to localities with smaller populations. Many of us represent districts containing no or few localities with populations above 500,000. Like their larger neighbors, though, these smaller counties, cities, and towns have faced enormous costs while responding to the COVID-19 pandemic. These costs include deploying timely public service announcements to keep Americans informed, rapidly activating emergency operations, readying employees for telework to keep services running, and more. This work is essential to keeping our constituents safe and mitigating the spread of the coronavirus as effectively as possible. We fear that, without targeted stabilization funding, smaller localities will be unable to continue providing these critical services to our constituents at the rate they are currently. We applaud you for including a $200 billion Coronavirus Relief Fund as part of H.R. -

May 11, 2020 the Honorable Gene L. Dodaro

May 11, 2020 The Honorable Gene L. Dodaro Comptroller General U.S. Government Accountability Office 441 G Street, NW Washington, D.C. 20416 Dear Comptroller General Dodaro: We write to request that the U.S. Government Accountability Office (GAO) investigate the allocation of loans under the Coronavirus Aid, Relief, and Economic Security (CARES) Act’s Paycheck Protection Program (PPP) to large, publicly traded companies.1 The PPP loans were created to help small businesses that have suffered financially as a result of the coronavirus outbreak because of stay-at-home orders. Businesses are eligible for PPP loans if they have 500 or fewer employees, or if the business meets applicable Small Business Association (SBA) employee-based size standards for that industry.2 For example, an oil and gas extraction company qualifies as a small business if at 1,250 employees or less. 3 A winery with 1,000 employees or less also constitutes a small business under SBA standards.4 An additional carve out in the statute also allows businesses that have more than one physical location, but do not employ more than 500 employees per physical location and are assigned a “North American Industry Classification code beginning with 72,” meaning the hotel and restaurant industry, to apply for the loans.5 There is no doubt that the many larger industries, including the hotel and restaurant industries, have taken a hard hit as a result of the coronavirus; however, larger companies often have greater access to cash and lines of credit. Yet, nearly 300 publicly traded companies, some with market values well over $100 million, received PPP loans.6 In fact, the largest known recipient of loans was a publicly traded firm, Ashford, Inc. -

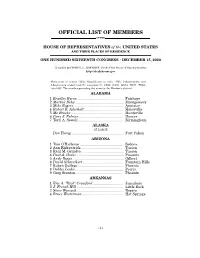

Official List of Members

OFFICIAL LIST OF MEMBERS OF THE HOUSE OF REPRESENTATIVES of the UNITED STATES AND THEIR PLACES OF RESIDENCE ONE HUNDRED SIXTEENTH CONGRESS • DECEMBER 15, 2020 Compiled by CHERYL L. JOHNSON, Clerk of the House of Representatives http://clerk.house.gov Democrats in roman (233); Republicans in italic (195); Independents and Libertarians underlined (2); vacancies (5) CA08, CA50, GA14, NC11, TX04; total 435. The number preceding the name is the Member's district. ALABAMA 1 Bradley Byrne .............................................. Fairhope 2 Martha Roby ................................................ Montgomery 3 Mike Rogers ................................................. Anniston 4 Robert B. Aderholt ....................................... Haleyville 5 Mo Brooks .................................................... Huntsville 6 Gary J. Palmer ............................................ Hoover 7 Terri A. Sewell ............................................. Birmingham ALASKA AT LARGE Don Young .................................................... Fort Yukon ARIZONA 1 Tom O'Halleran ........................................... Sedona 2 Ann Kirkpatrick .......................................... Tucson 3 Raúl M. Grijalva .......................................... Tucson 4 Paul A. Gosar ............................................... Prescott 5 Andy Biggs ................................................... Gilbert 6 David Schweikert ........................................ Fountain Hills 7 Ruben Gallego ............................................ -

Rivalidade Hegemônica E Sociedade Civil No Golfo Da Guiné No Século XXI

Rivalidade hegemônica e sociedade civil no Golfo da Guiné no século XXI HENRY KAM KAH Resumo: Este texto examina o envolvimento crucial das grandes potências na identificação e exploração de recursos naturais e humanos no estratégico Golfo da Guiné localizado na África. Por variadas razões, tal intervenção produziu esferas de influência hegemônica e confrontos neocoloniais de vários tipos. A guerra de palavras e outras práticas pouco ortodoxas iniciadas por esses poderes e apoiadas por alguns de seus representantes africanos desencadeou uma crescente mobilização de organizações da sociedade civil. Palavras-chave: África. Golfo da Guiné; Neocolonialismo; Sociedade Civil. Hegemonic rivalry and emerging civil society in the Gulf of Guinea in the 21st century Abstract: This paper examined the critical engagement of the major powers in the identification and exploitation of natural and human resources in the strategically located Gulf of Guinea, in Africa. For multifarious reasons, this intervention has produced spheres of hegemonic influence and neo-colonial clashes of various kinds. The war of words and other unorthodox practices initiated by these powers and supported by some African surrogates has unleashed a growing mobilisation of civil society organisations. Keywords: Africa; Gulf of Guinea; HENRY KAM KAH Neocolonialism; Civil Society. Professor da Universidade de Buea, Camarões. RECEBIDO EM: 05 DE AGOSTO DE 2015 [email protected] APROVADO EM: 10 DE SETEMBRO DE 2015 TENSÕES MUNDIAIS | 203 HENRY KAM KAH 1 INTRODUCTION: MOMENTOUS ISSUES AND ACTORS IN THE GULF OF GUINEA The greater Gulf of Guinea with an area of nearly 3500 miles of coastline is one of the strategic regions of Africa which is also blessed with a variety of natural resources such as oil, gas, diverse minerals and human resources. -

House Organic Caucus Members

HOUSE ORGANIC CAUCUS The House Organic Caucus is a bipartisan group of Representatives that supports organic farmers, ranchers, processors, distributors, retailers, and consumers. The Caucus informs Members of Congress about organic agriculture policy and opportunities to advance the sector. By joining the Caucus, you can play a pivotal role in rural development while voicing your community’s desires to advance organic agriculture in your district and across the country. WHY JOIN THE CAUCUS? Organic, a $55-billion-per-year industry, is the fastest-growing sector in U.S. agriculture. Growing consumer demand for organic offers a lucrative market for small, medium, and large-scale farms. Organic agriculture creates jobs in rural America. Currently, there are over 28,000 certified organic operations in the U.S. Organic agriculture provides healthy options for consumers. WHAT DOES THE EDUCATE MEMBERS AND THEIR STAFF ON: CAUCUS DO? Keeps Members Organic farming methods What “organic” really means informed about Organic programs at USDA opportunities to Issues facing the growing support organic. organic industry TO JOIN THE HOUSE ORGANIC CAUCUS, CONTACT: Kris Pratt ([email protected]) in Congressman Peter DeFazio’s office Ben Hutterer ([email protected]) in Congressman Ron Kind’s office Travis Martinez ([email protected]) in Congressman Dan Newhouse’s office Janie Costa ([email protected]) in Congressman Rodney Davis’s office Katie Bergh ([email protected]) in Congresswoman Chellie Pingree’s office 4 4 4 N . C a p i t o l S t . N W , S u i t e 4 4 5 A , W a s h i n g t o n D . -

A Bipartisan Letter to Speaker of the House Nancy Pelosi And

May 28, 2020 The Honorable Nancy Pelosi The Honorable Kevin McCarthy Speaker of the House Minority Leader U.S. House of Representatives U.S. House of Representatives H-232, U.S. Capitol H-204, U.S. Capitol Washington, D.C. 20515 Washington, D.C. 20515 Dear Speaker Pelosi and Leader McCarthy: Thank you for your swift action and continuing efforts as we grapple with the COVID-19 pandemic. The Coronavirus Aid, Relief, and Economic Security (CARES) Act (PL 116-136) provided our physical therapists, occupational therapists, and speech-language pathologists with much-needed and meaningful aid to continue patient care operations during this pandemic, the effects of which could be felt for years. However, while Congress is diligently working to protect these important medical practices, they are being targeted for a sizeable cut that is slated to be finalized within the next few weeks. The Centers for Medicare and Medicaid Services’ (CMS) final CY2020 Medicare Physician Fee Schedule rule published in November 2019 proposed increased rates for the office-based evaluation and management (E/M) code set in CY2021. Due to the requirement for budget neutrality, this would result in a projected eight percent cut for therapy services beginning on January 1, 2021. If these cuts are allowed to go into effect, they will be devasting and will limit access to care for patients, including seniors, who rely on these services. Ultimately, these cuts will force physical and occupational clinics to close, resulting in thousands of qualified professional clinicians, especially those in rural and urban areas in our districts, to lose their jobs. -

5442 Hon. C.A. Dutch Ruppersberger Hon

5442 EXTENSIONS OF REMARKS March 17, 2005 TRIBUTE TO PETTY OFFICER Rowland of Montross, Va., who died on March STATEMENT IN HONOR OF JUDI ANDREA BISIGNANI 6th at the Virginia Veterans Care Center in KANTER Roanoke at the age of 87. John’s daughter, HON. C.A. DUTCH RUPPERSBERGER Michelle served on my staff and Michelle often HON. ZOE LOFGREN OF MARYLAND spoke of her father and his commitment to his OF CALIFORNIA IN THE HOUSE OF REPRESENTATIVES country. IN THE HOUSE OF REPRESENTATIVES Thursday, March 17, 2005 Sgt. Rowland was born September 1, 1917 Thursday, March 17, 2005 Mr. RUPPERSBERGER. Mr. Speaker, I rise in Fayette, Alabama and spent most of his today to pay tribute to Petty Officer (FSO) An- childhood in Westbrook, Texas. After grad- Ms. ZOE LOFGREN of California. Mr. drea Bisignani. uating from Westbrook High School in 1934, Speaker, on behalf of the women of the Cali- FS2 Andrea Bisignani, a Food Service Spe- he worked the oil fields of Western Texas for fornia Democratic Congressional Delegation, I cialist on the Coast Guard Cutter James Standard Oil. am proud to pay tribute to our friend Judi Kanter on her retirement from EMILY’s List. It Rankin, is being honored as the 2005 Balti- John Rowland enlisted in the Army in 1940 more Area Coast Guard Person of the Year. is a pleasure and an honor to recognize Judi and served with the 36th ID, 142nd Infantry, FS2 Bisignani has consistently dem- Kanter for fifteen years of outstanding work Antitank Company (the T-Patchers) until June onstrated a high level of performance through- with EMILY’s List, where she has been a lead- 1945. -

Congress of the United States Washington D.C

Congress of the United States Washington D.C. 20515 April 29, 2020 The Honorable Nancy Pelosi The Honorable Kevin McCarthy Speaker of the House Minority Leader United States House of Representatives United States House of Representatives H-232, U.S. Capitol H-204, U.S. Capitol Washington, D.C. 20515 Washington, D.C. 20515 Dear Speaker Pelosi and Leader McCarthy: As Congress continues to work on economic relief legislation in response to the COVID-19 pandemic, we ask that you address the challenges faced by the U.S. scientific research workforce during this crisis. While COVID-19 related-research is now in overdrive, most other research has been slowed down or stopped due to pandemic-induced closures of campuses and laboratories. We are deeply concerned that the people who comprise the research workforce – graduate students, postdocs, principal investigators, and technical support staff – are at risk. While Federal rules have allowed researchers to continue to receive their salaries from federal grant funding, their work has been stopped due to shuttered laboratories and facilities and many researchers are currently unable to make progress on their grants. Additionally, researchers will need supplemental funding to support an additional four months’ salary, as many campuses will remain shuttered until the fall, at the earliest. Many core research facilities – typically funded by user fees – sit idle. Still, others have incurred significant costs for shutting down their labs, donating the personal protective equipment (PPE) to frontline health care workers, and cancelling planned experiments. Congress must act to preserve our current scientific workforce and ensure that the U.S.