University of Cape Town (UCT) in Terms of the Non-Exclusive License Granted to UCT by the Author

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

(Special Trip) XXXX WER Yes AANDRUS, Bloemfontein 9300

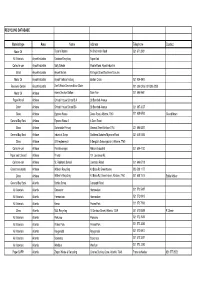

Place Name Code Hub Surch Regional A KRIEK (special trip) XXXX WER Yes AANDRUS, Bloemfontein 9300 BFN No AANHOU WEN, Stellenbosch 7600 SSS No ABBOTSDALE 7600 SSS No ABBOTSFORD, East London 5241 ELS No ABBOTSFORD, Johannesburg 2192 JNB No ABBOTSPOORT 0608 PTR Yes ABERDEEN (48 hrs) 6270 PLR Yes ABORETUM 3900 RCB Town Ships No ACACIA PARK 7405 CPT No ACACIAVILLE 3370 LDY Town Ships No ACKERVILLE, Witbank 1035 WIR Town Ships Yes ACORNHOEK 1 3 5 1360 NLR Town Ships Yes ACTIVIA PARK, Elandsfontein 1406 JNB No ACTONVILLE & Ext 2 - Benoni 1501 JNB No ADAMAYVIEW, Klerksdorp 2571 RAN No ADAMS MISSION 4100 DUR No ADCOCK VALE Ext/Uit, Port Elizabeth 6045 PLZ No ADCOCK VALE, Port Elizabeth 6001 PLZ No ADDINGTON, Durban 4001 DUR No ADDNEY 0712 PTR Yes ADDO 2 5 6105 PLR Yes ADELAIDE ( Daily 48 Hrs ) 5760 PLR Yes ADENDORP 6282 PLR Yes AERORAND, Middelburg (Tvl) 1050 WIR Yes AEROTON, Johannesburg 2013 JNB No AFGHANI 2 4 XXXX BTL Town Ships Yes AFGUNS ( Special Trip ) 0534 NYL Town Ships Yes AFRIKASKOP 3 9860 HAR Yes AGAVIA, Krugersdorp 1739 JNB No AGGENEYS (Special trip) 8893 UPI Town Ships Yes AGINCOURT, Nelspruit (Special Trip) 1368 NLR Yes AGISANANG 3 2760 VRR Town Ships Yes AGULHAS (2 4) 7287 OVB Town Ships Yes AHRENS 3507 DBR No AIRDLIN, Sunninghill 2157 JNB No AIRFIELD, Benoni 1501 JNB No AIRFORCE BASE MAKHADO (special trip) 0955 PTR Yes AIRLIE, Constantia Cape Town 7945 CPT No AIRPORT INDUSTRIA, Cape Town 7525 CPT No AKASIA, Potgietersrus 0600 PTR Yes AKASIA, Pretoria 0182 JNB No AKASIAPARK Boxes 7415 CPT No AKASIAPARK, Goodwood 7460 CPT No AKASIAPARKKAMP, -

Applications

APPLICATIONS PUBLICATIONS AREAS BUSINESS NAMES AUGUST 2021 02 09 16 23 30 INC Observatory, Rondebosch East, Lansdowne, Newlands, Rondebosch, Rosebank, Mowbray, Bishopscourt, Southern Suburbs Tatler Claremont, Sybrand Park, Kenilworth, Pinelands, Kenwyn, BP Rosemead / PnP Express Rosemead Grocer's Wine 26 Salt River, Woodstock, University Estate, Walmer Estate, Fernwood, Harfield, Black River Park Hazendal, Kewtown, Bridgetown, Silvertown, Rylands, Newfields, Gatesville, Primrose Park, Surrey Estate, Heideveld, Athlone News Shoprite Liquorshop Vangate 25 Pinati, Athlone, Bonteheuwel, Lansdowne, Crawford, Sherwood Park, Bokmakierie, Manenberg, Hanover Park, Vanguard Deloitte Cape Town Bantry Bay, Camps Bay, Clifton, De Waterkant, Gardens, Green Point, Mouille Point, Oranjezicht, Schotsche Kloof, Cape Town Wine & Spirits Emporium Atlantic Sun 26 Sea Point, Tamboerskloof, Three Anchor Bay, Vredehoek, V & A Marina Accommodation Devilspeak, Zonnebloem, Fresnaye, Bakoven Truman and Orange Bergvliet, Diep River, Tokai, Meadowridge, Frogmore Estate, Southfield, Flintdale Estate, Plumstead, Constantia, Wynberg, Kirstenhof, Westlake, Steenberg Golf Estate, Constantia Village, Checkers Liquorshop Westlake Constantiaberg Bulletin 26 Silverhurst, Nova Constantia, Dreyersdal, Tussendal, John Collins Wines Kreupelbosch, Walloon Estate, Retreat, Orchard Village, Golf Links Estate Blouberg, Table View, Milnerton, Edgemead, Bothasig, Tygerhof, Sanddrift, Richwood, Blouberg Strand, Milnerton Ridge, Summer Greens, Melkbosstrand, Flamingo Vlei, TableTalk Duynefontein, -

South Africa) Over a Two-Year Period

Retrospective analysis of blunt force trauma associated with fatal road traffic accidents in Cape Town (South Africa) over a two-year period. by T. A Tiffany Majero (MJRTIN002) Town SUBMITTED TO THE UNIVERSITYCape OF CAPE TOWN In partial fulfilment of the requirements for the degree of MPhil (Biomedical Forensic Science) Faculty of Health Sciences UNIVERSITY OF CAPE TOWN University November 2017 Supervisors: Calvin Mole Department of Pathology Division of Forensic Medicine and Toxicology University of Cape Town The copyright of this thesis vests in the author. No quotation from it or information derived from it is to be published without full acknowledgementTown of the source. The thesis is to be used for private study or non- commercial research purposes only. Cape Published by the University ofof Cape Town (UCT) in terms of the non-exclusive license granted to UCT by the author. University TURNIT IN REPORT ii | P a g e DECLARATION I, T. A. Tiffany Majero, hereby declare that the work on which this dissertation/thesis is based is my original work (except where acknowledgements indicate otherwise) and that neither the whole work nor any part of it has been, is being, or is to be submitted for another degree in this or any other university. I empower the university to reproduce for the purpose of research either the whole or any portion of the contents in any manner whatsoever. Signature : Date : February 2018 iii | P a g e ABSTRACT Road transportation systems are a global developmental achievement. However, with them comes increased morbidity and mortality rates in the form of road traffic accidents. -

Reflections on Identity in Four African Cities

Reflections on Identity in Four African Cities Lome Edited by Libreville Simon Bekker & Anne Leildé Johannesburg Cape Town Simon Bekker and Anne Leildé (eds.) First published in 2006 by African Minds. www.africanminds.co.za (c) 2006 Simon Bekker & Anne Leildé All rights reserved. ISBN: 1-920051-40-6 Edited, designed and typeset by Compress www.compress.co.za Distributed by Oneworldbooks [email protected] www.oneworldbooks.com Contents Preface and acknowledgements v 1. Introduction 1 Simon Bekker Part 1: Social identity: Construction, research and analysis 2. Identity studies in Africa: Notes on theory and method 11 Charles Puttergill & Anne Leildé Part 2: Profiles of four cities 3. Cape Town and Johannesburg 25 Izak van der Merwe & Arlene Davids 4. Demographic profiles of Libreville and Lomé 45 Hugues Steve Ndinga-Koumba Binza Part 3: Space and identity 5. Space and identity: Thinking through some South African examples 53 Philippe Gervais-Lambony 6. Domestic workers, job access, and work identities in Cape Town and Johannesburg 97 Claire Bénit & Marianne Morange 7. When shacks ain’t chic! Planning for ‘difference’ in post-apartheid Cape Town 97 Steven Robins Part 4: Class, race, language and identity 8. Discourses on a changing urban environment: Reflections of middle-class white people in Johannesburg 121 Charles Puttergill 9. Class, race, and language in Cape Town and Johannesburg 145 Simon Bekker & Anne Leildé 10. The importance of language identities to black residents of Cape Town and Johannesburg 171 Robert Mongwe 11. The importance of language identities in Lomé and Libreville 189 Simon Bekker & Anne Leildé Part 5: The African continent 12. -

A People's Led Approach to Informal Settlement

Exploring partnerships with local government A PEOPLE’S LED APPROACH TO INFORMAL SETTLEMENT UPGRADING Published by CORC, November 2018 © Community Organisation Resource Centre (CORC) Hendler, Y. & Fieuw, W. 2018. Exploring partnerships with local government: A people’s led approach to informal settlement upgrading. CORC, Cape Town. This publication was authored by Yolande Hendler (CORC) and Walter Fieuw (Making of Cities). Bunita Kohler (CORC) played an important role in content conceptualisation and editing. The publication was designed by arqino.com This publication is dedicated to FEDUP and ISN. Special acknowledgement and thanks to the communities of: Joe Slovo, Langa Sheffield Road, Philippi Mtshini Wam, Joe Slovo Park, Milnerton Flamingo Crescent, Lansdowne California, Mfuleni Exploring partnerships with local government Foreword A people’s led approach to informal settlement upgrading Upgrading informal settlements is now widely accepted by governments and international David Satterthwaite agencies as the most effective way to improve conditions for their inhabitants. Such upgrading is endorsed by the Sustainable Development Goals along with a commitment to ensure access International Institute for all to adequate, safe and affordable housing and basic services by 2030. for Environment and Development (IIED) But citizen and community led upgrading was first recommended in the 1960s. Why has it taken 50 years to gain this acceptance? Why are there are still so many examples of bulldozing rather than upgrading informal settlements? Even where upgrading is accepted, there are still many challenges. Some upgrading schemes just provide such rudimentary improvements (e.g. communal water gaps and better drainage). Then there are the challenges for governments and community organisations to increase scale – going from one or two small successful upgrading initiatives to supporting initiatives in a much larger and more diverse range of settlements. -

Material Type Area Name Address Telephone Contact RECYCLING DATABASE

RECYCLING DATABASE Material type Area Name Address Telephone Contact Motor Oil - Taylor's Motors 14 Chichester Road 021 671 2931 All Materials Airport Industria Rainbow Recycling Airport Ind Collect-a-can Airport Industria Solly Sebola Mobile Road, Airpot industria Metal Airport Industria Airport Metals Michigan Street/'Northern Suburbs Motor Oil Airport Industria Airport Vehicle Testing Boston Circle 021 934 4900 Recovery Centre Airport Industria Don't Waste Services Brian Slater 021 386 0206 / 021 386 0208 Motor Oil Athlone Adens Service Station Eden Ave 021 696 9941 Paper-Mondi Athlone Christel House School S A 38 Bamford Avenue Other Athlone Christel House School SA 38 Bamford Avenue 021 697 3037 Glass Athlone Express Waste Desre Road, Athlone, 7760 021 638 6593 Gerard Moen General Buy Back Athlone Express Waste 2 5 Desri Road Glass Athlone Garlandale Primary General Street Athlone 7764 021 696 8327 General Buy Back Athlone Industrial Scrap Southern Suburbs/'Mymona Road 021 448 5395 Glass Athlone LR Heydenreych 5 Bergzich Schoongezicht, Athlone, 7760 Collect-a-can Athlone Pen Beverages Athlone Industrial 021 684 4130 Paper and C/board Athlone Private 151 Lawrence Rd, Collect-a-can Athlone St. Raphaels School Lawrence Road 021 696 6718 Glass/ tins/ plastic Athlone Walkers Recycling 43 Brian Rd Greenhaven 083 508 1177 Glass Athlone Walker's Recycling 43 Brian Rd, Greenhaven, Athlone, 7760 021 638 1515 Eddie Walker General Buy Back Atlantis Berties Scrap Conaught Road All Materials Atlantis Grosvenor Hermeslaan 021 572 5487 All Materials -

Supporting Reblocking and Community Development in Mtshini

Supporting Reblocking and Community Development in Mtshini Wam Abstract The South African government is currently facing immense pressure to provide all citizens with access to housing and basic services. In response to the historically slow and unsustainable sys- tem of housing and service delivery for informal communities across South Africa, a process called reblocking was created. The informal settlement community of Mtshini Wam and our sponsor, Community Organisation Resource Centre (CORC), invited us to observe the first re- blocking project undertaken in partnership with the City of Cape Town and the Informal Settle- ment Network (ISN). Our project goal was to support this reblocking process as well as communi- ty development. At the partnership’s request, we created a guidebook to help streamline this process as the new standard of informal settlement improvement. We also utilised momentum from the reblocking process to implement community driven initiatives addressing issues of food security, entrepreneurial job opportunities, and quality and safety of shack dwelling. For our full project report: http://wp.wpi.edu/capetown/homepage/projects/p2012/mtshini-wam For more about the Cape Town Project Centre: http://wp.wpi.edu/capetown/ Authors Project Advisors Sponsors An Interactive Qualifying Project to be submitted to the faculty of Worcester Polytechnic Zachary Hennings Professors Robert Hersh Community Organisation Rachel Mollard Resource Centre Institute in partial fulfillment of the requirements for the Degree of Bachelor Science. and Scott Jiusto Adam Moreschi Sarah Sawatzki Stephen Young were unable or unwilling to pay for their Understand the process Background formal services and either sold their houses of reblocking, the reasons or rented their backyards to shack dwellers. -

C . __ P Ar T 1 0 F 2 ...,.)

March Vol. 669 12 2021 No. 44262 Maart C..... __ P_AR_T_1_0_F_2_....,.) 2 No. 44262 GOVERNMENT GAZETTE, 12 MARCH 2021 Contents Page No. Transport, Department of / Vervoer, Departement van Cross Border Road Transport Agency: Applications for Permits Menlyn ............................................................................................................................... 3 Applications Concerning Operating Licences Goodwood ......................................................................................................................... 7 Goodwood ......................................................................................................................... 23 Goodwood ......................................................................................................................... 76 Johannesburg – GPGTSHW968 ....................................................................................... 119 STAATSKOERANT, 12 Maart 2021 No. 44262 3 CROSS-BORDER ROAD TRANSPORT AGENCY APPLICATIONS FOR PERMITS Particulars in respect of applications for permits as submitted to the Cross-Border Road Transport Agency, indicating, firstly, the reference number, and then- (i) the name of the applicant and the name of the applicant's representative, if applicable. (ii) the country of departure, destination and, where applicable, transit. (iii) the applicant's postal address or, in the case of a representative applying on behalf of the applicant, the representative's postal address. (iv) the number and type of vehicles, -

January 2020 Removal Applications.Pdf

South African Police Name under which Services designated liquor Full name of applicant business will be Address of the proposed premises Kind of licence applied for officer office where the Newspaper Publication Date Distribution Area Circulation conducted application has been lodged Firgrove Business Park, Unit C5, 9 1 Eurolane CC Eurolane Quantum Road, Firgrove, Somerset Off-Consumption Somerset West Bolander 29/01/2020 Strand, Somerset West, Franschhoek, Paarl, Stellenbosch, Gordon's Bay, Wellington. 31,150 West Blouberg, Table View, Milnerton, Edgemead, Bothasig, Tygerhof, Sanddrift, Richwood, Blouberg Strand, Milnerton Creation Park, Unit 37 & 38, 2 Ridge, Summer Greens, Melkbosstrand, Sunridge, Flamingo Vlei, West Riding, Duynefontein, Van Riebeeckstrand, Milnerton 2 Anchor Chandling (Pty) Ltd Anchor Chandling Computer Road, Marconi Beam, Off-Consumption TableTalk 29/01/2020 Sunset Beach, West Beach, Parklands, Phoenix, Sunningdale, Blouberg Sands, Killarney Gardens, Montague Gardens, 67,673 Maitland Milnerton Sunset Village, Sunset Links, Big Bay, Joe Slovo Park, Century City Residential, De Noon, Royal Ascot, Brooklyn, Rugby, Paarden Eiland. Woodstock People's Post - Salt River, University Estate, Walmer Estate, Woodstock, Observatory, Paardeneiland, Factreton, Kensington, 3 Rocket Trading 103 CC Honestar Asia Supermarket 359 Albert Road, Woodstock Off-Consumption 28/01/2020 14,825 Gordon’s Bay Woodstock/Maitland Maitland, Maitland Garden Village Crazy Horse Investment (Pty) Shop 37, Mountain Mill Shopping Worcester, Touwsrivier, -

Sub Place Health Education Income HDI Atlantis 0.612 0.88 0.88 0.79

HDIs FOR CAPE TOWN AREAS (alphabetical by area) Sub Place Health Education Income HDI Atlantis 0.612 0.88 0.88 0.79 Bellville 0.692 0.93 0.95 0.86 Blue Downs 0.472 0.86 0.79 0.71 Brackenfell 0.692 0.89 0.88 0.82 Briza 0.692 0.95 0.99 0.88 Cape Town 0.667 0.88 0.91 0.82 Crossroads 0.472 0.89 0.67 0.68 Du Noon 0.472 0.78 0.65 0.63 Durbanville 0.692 0.95 1.00 0.88 Eerste River 0.692 0.90 0.84 0.81 Elsies River 0.472 0.82 0.79 0.70 Excelsior 0.692 0.89 0.83 0.80 Fisantekraal 0.472 0.79 0.66 0.64 Fish Hoek 0.658 0.96 0.95 0.85 Goodwood 0.613 0.95 0.94 0.84 Gordon’s Bay 0.692 0.95 0.94 0.86 Gugulethu 0.472 0.93 0.74 0.71 Hottentotsholland 0.692 1.00 0.65 0.78 Nature Reserve Hout Bay 0.612 0.89 1.00 0.83 Imizamo Yethu 0.472 0.84 0.67 0.66 Joe Slovo Park 0.472 0.99 0.68 0.71 Khayelitsha 0.472 0.90 0.69 0.69 Kraaifontein 0.472 0.88 0.85 0.73 Kuils River 0.612 0.90 0.91 0.81 Langa 0.472 0.92 0.70 0.70 Lekkerwater 0.472 0.79 0.60 0.62 Lwandle 0.472 0.87 0.64 0.66 Mamre 0.417 0.85 0.79 0.69 Masiphumelele 0.472 0.84 0.65 0.65 Melkbosstrand 0.692 0.95 1.01 0.89 continued overleaf.. -

Integrated Rapid Transport: Is the City of Cape Town Utilising Its Full Potential?

Integrated Rapid Transport: Is the City of Cape Town utilising its full potential? M. STRYDOM 20063016 Dissertation submitted in fulfilment of the requirements for the degree Master of Arts and Science (Planning) in Town and Regional Planning at the (Potchefstroom Campus) of the North-West University Supervisor: Prof. C.B. Schoeman November 2010 ACKNOWLEDGEMENTS He gives power to the weak and strength to the powerless. Even youths will become weak and tired, and young men will fall in exhaustion. But those who trust in the LORD will find new strength. They will soar high on wings like eagles. They will run and not grow weary. They will walk and not faint. Isaiah 40:29-31 It’s all for You Father. I have truly been blessed with the world’s greatest family and no words can even nearly express how much I love you all. I want to thank my Daddy, you have always wanted only the best for me and have always been behind me pushing me to succeed. Without your love, faith and support none of this would have been possible. I could not have asked for a better dad! My Mami, the person on the other side of 99.9% of all my conversations. You are my best friend. You have taught me countless priceless life lessons and I am honoured to call you my mom. Uncle, your faith, love and support has never gone unnoticed, thank you. My big sister Annemi, you are an inspiration to me in so many ways; I look up to you and are so proud to call you my sister. -

Xenophobia and the Role of Immigrant Organizations in the City of Cape Town

Xenophobia and the role of immigrant organizations in the city of Cape Town Denys UWIMPUHWE Student Number: 3209825 PhD THESIS SUBMITTED TO THE SCHOOL OF GOVERNMENT, FACULTY OF ECONOMIC AND MANAGEMENT SCIENCES, UNIVERSITY OF THE WESTERN CAPE In Fulfilment of the Requirements for the Degree, Doctor of Philosophy in Public Administration In the Faculty of Economic Management Science (EMS) At the University of Western Cape (UWC) Supervisor: Prof. Greg Ruiters December 2015 UWC copyright information The dissertation/thesis may not be published either in part (in scholarly, scientific or technical journals), or as a whole (as a monograph), unless permission has been obtained from the University ii DECLARATION I, Denys Uwimpuhwe, declare that the contents of this thesis represent my own unaided work, and that the dissertation/thesis has not previously been submitted for academic examination towards any qualification. Furthermore, it represents my own opinions and not necessarily those of the University. Signed Date iii ABSTRACT The aim of this study is to develop an understanding of Cape Town’s foreign African immigrants by looking at the profile, character and role of immigrant associations and how they shape survival strategies as well as possible paths to the integration of African immigrants. The thesis seeks to develop an understanding of the mediating role played by Cape Town’s African foreign immigrant organisations. I also look at the transnational activities of these organizations. I selected Cape Town because it prides itself on liberal values of toleration, diversity and non-racialism while at the same time branding itself as an African City. The City of Cape Town has no comprehensive policy that protects or promotes the immigrants’ interests.