Comment Bailey:Mastercomment.Qxd

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

An Estimate of the Number of Animals Used for Scientific Purposes

Research Article Alternatives to Laboratory Animals 1–18 ª The Author(s) 2020 An Estimate of the Number of Animals Article reuse guidelines: sagepub.com/journals-permissions Used for Scientific Purposes Worldwide DOI: 10.1177/0261192919899853 in 2015 journals.sagepub.com/home/atl Katy Taylor and Laura Rego Alvarez Abstract Few attempts have been made to estimate the global use of animals in experiments, since our own estimated figure of 115.2 million animals for the year 2005. Here, we provide an update for the year 2015. Data from 37 countries that publish national statistics were standardised against the definitions of ‘animals’ and ‘procedures’ used in the European Union (EU) Directive 2010/63/EU. We also applied a prediction model, based on publication rates, to estimate animal use in a further 142 countries. This yielded an overall estimate of global animal use in scientific procedures of 79.9 million animals, a 36.9% increase on the equivalent estimated figure for 2005, of 58.3 million animals. We further extrapolated this estimate to obtain a more comprehensive final global figure for the number of animals used for scientific purposes in 2015, of 192.1 million. This figure included animals killed for their tissues, normal and genetically modified (GM) animals without a harmful genetic mutation that are used to maintain GM strains and animals bred for laboratory use but not used. Since the 2005 study, there has been no evident increase in the number of countries publishing data on the numbers of animals used in experiments. Without regular, accurate statistics, the impact of efforts to replace, reduce and refine animal experiments cannot be effectively monitored. -

Derogatory Discourses of Veganism and the Reproduction of Speciesism in UK 1 National Newspapers Bjos 1348 134..152

The British Journal of Sociology 2011 Volume 62 Issue 1 Vegaphobia: derogatory discourses of veganism and the reproduction of speciesism in UK 1 national newspapers bjos_1348 134..152 Matthew Cole and Karen Morgan Abstract This paper critically examines discourses of veganism in UK national newspapers in 2007. In setting parameters for what can and cannot easily be discussed, domi- nant discourses also help frame understanding. Discourses relating to veganism are therefore presented as contravening commonsense, because they fall outside readily understood meat-eating discourses. Newspapers tend to discredit veganism through ridicule, or as being difficult or impossible to maintain in practice. Vegans are variously stereotyped as ascetics, faddists, sentimentalists, or in some cases, hostile extremists. The overall effect is of a derogatory portrayal of vegans and veganism that we interpret as ‘vegaphobia’. We interpret derogatory discourses of veganism in UK national newspapers as evidence of the cultural reproduction of speciesism, through which veganism is dissociated from its connection with debates concerning nonhuman animals’ rights or liberation. This is problematic in three, interrelated, respects. First, it empirically misrepresents the experience of veganism, and thereby marginalizes vegans. Second, it perpetuates a moral injury to omnivorous readers who are not presented with the opportunity to understand veganism and the challenge to speciesism that it contains. Third, and most seri- ously, it obscures and thereby reproduces -

Ar Calendar.P65

May 2012 Animal Rights Calendar Sat 12th . West Lancashire Vegan Fair Sat 12th . Global Boycott Procter & Gamble Day (TBC). Uncaged www.veggies.org.uk/arc.htm Sat 19th . Meat Free in Manchester : Vegetarian Society Sat 19th . Hugletts Wood Farm Animal Sanctuary Open Day Sun 20th . Horse and Pony Sanctuary Open Day March 2012 : Veggie Month : Animal Aid Mon 21st - Sun 27th . National Vegetarian Week Mon 5th . Sheffield Animal Friends meeting Fri 25th - Sun 27th . Bristol VegFestUK Mon 5th . Manchester Animal Action! 1st Monday monthly Sun 27th . GM Action Tue 6th . South East Animal Rights meeting. First Tuesday of each month. Tue 6th . Merseyside Animal Rights meeting. First Tuesday monthly June 2012 Sun 10th . Animals in Need Sponsored Walk Wed 7th . Live Exports - Ramsgate (every week) : Kent Action Against Live Exports (KAALE) Sun 10th . Nottingham Green Festival (T.B.C) Wed 7th . Derby Animal Rights. Every two weeks. Tue 19th . McLibel: Anniversary Day of Action Wed 7th . Southsea Animal Action meeting. First Wednesday monthly Wed 7th . Ethical Voice for Animals meeting. First Wednesday monthly July 2012 Wed 7th . Southampton Animal Action. First Wednesday monthly Thur 5th . Mel Broughton's Birthday : Vegan Prisoner Support Group Thur 8th . Nottingham Animal Rights Networking. Every two weeks Sat 7th . Animal Aid Sponsored Walk Fri 13th - Sun 15th . International Animal Rights Gathering, Poland Sat 10th . Demo against proposed cull Lake Windermere Canada Geese Mon 12th . Bath Animal Action / Hunt Sabs. 2nd Monday monthly August 2012 Wed 14th . Bournemouth Animal Aid Meeting. 2nd Wednesday monthly Wed 1st - Mon 6th . EF Summer Gathering, Shrewsbury Wed 14th . Taunton Vegans & Veggies. -

Veterinary Students' Perception and Understanding of Issues

animals Article Veterinary Students’ Perception and Understanding of Issues Surrounding the Slaughter of Animals According to the Rules of Halal: A Survey of Students from Four English Universities Awal Fuseini * , Andrew Grist and Toby G. Knowles School of Veterinary Science, University of Bristol, Langford, Bristol BS40 5DU, UK; [email protected] (A.G.); [email protected] (T.G.K.) * Correspondence: [email protected]; Tel.: +44-074-7419-2392 Received: 18 April 2019; Accepted: 27 May 2019; Published: 30 May 2019 Simple Summary: Veterinarians play a vital role in safeguarding the welfare of animals and protecting public health during the slaughter of farm animals for human consumption. With the continued increase in the number of animals slaughtered for religious communities in the UK, this study evaluates the perception and level of understanding of religious slaughter issues by veterinary students at various stages of their studies. The results showed a significant effect of the year of study on respondents’ understanding of the regulations governing Halal slaughter and other related issues. Whilst the prevalence of vegetarianism and veganism were higher than the general UK population, the majority of respondents were meat eaters who indicated that they prefer meat from humanely slaughtered (pre-stunned) animals, irrespective of whether slaughter was performed with an Islamic prayer (Halal) or not. Abstract: The objective of this study was to evaluate the perception and level of understanding of religious slaughter issues, and the regulations governing the process, amongst veterinary students in England. A total of 459 veterinary students in different levels, or years of study (years 1–5), were surveyed. -

About Animal Aid Animal Aid Is the Largest Animal Rights Pressure Group in the UK

About Animal Aid Animal Aid is the largest animal rights pressure group in the UK. The society campaigns against all forms of animal abuse and promotes a cruelty-free lifestyle. Animal Aid’s origins The story of Animal Aid began in 1977, when school teacher Jean Pink read a book by philosopher Peter Singer called ‘Animal Liberation’. This book exposed what was happening to animals in laboratories and factory farms. Jean couldn’t get the images of animal suffering out of her head and she decided she had to do something about it. She produced leaflets and petitions at home, and Target groups recruited a small group of supporters to hand them out The key target groups for Animal Aid’s campaigns are: to the public. The numbers of supporters grew, and Jean l the general public decided to give up teaching so that she could devote l politicians such as MPs, MEPs and government all her time to her campaigning work. She rented an l ministers. office in Tonbridge and established Animal Aid as a l the media, including TV, radio and newspapers pressure group. Animal Aid has grown today into the largest animal rights pressure group in the UK with many It is through the media, our website and special thousands of supporters. publications that we communicate our message to the public, who we hope will change their lifestyle and also lobby politicians to introduce laws to bring about change. As consumers, members of the public can also influence companies by, for example, buying cruelty-free products. Campaign methods Animal Aid’s main campaign methods include: l distributing films, leaflets, posters, factsheets, l l l postcards and reports l carrying out undercover investigations to expose l l l animal cruelty l e-campaigning via the internet and social media l lobbying politicians and businesses l organising demonstrations and publicity events l providing teaching resources free of charge to l l l schools Animal Aid’s campaigning policy is strictly peaceful. -

Promoting Local Philanthropy and Strengthening the Dear Neighbors and Friends, Nonprofit Organizations in Essex County, MA

Promoting local philanthropy and strengthening the Dear Neighbors and Friends, nonprofit organizations in Essex County, MA. If ever there were a time for a thriving Community Foundation, this is it. Charitable life in America has reached new levels of challenge and importance this year. When government is in difficult straits, when business is recovering, and when society’s Ayer Mill Clock Tower needs are growing, the nonprofit sector steps forward. Can charities become more effi- Turns 100! cient? Can donors give more effectively? Can they work together? Your Community Foundation is at the heart of the matter. This Report has news of ECCF’s October 3rd, 2010 marked the life in 2011: 100th Anniversary of the larg- est mill clock tower in the 2011 Record participation of leaders county-wide at the Institute for Trustees world. ECCF celebrated Significant increases in the breadth of grantmaking by ECCF Fund Holders the tower and its keeper, report A challenging fundraising year for ECCF and many other nonprofits Charlie Waites, with a A game-changing summit of nonprofit leaders in Lawrence reception at the Law- 6,800 Massachusetts nonprofits and 275,000 nationwide decertified by IRS as out rence History Center. ... Making a difference of business or out of compliance ECCF manages the maintenance of for those who make Record attendance at the Youth at Risk Conference in the face of major public the tower through a difference budget cuts an Endowment Wonderful new Trustees and staff helping ECCF expand its services and impact Fund established at the Foundation. Learn A year like 2011 shows just how essential it is for Essex County to have its Community more about the iconic Foundation. -

A Pocket Guide to Veganism

A Pocket Guide to Veganism What is veganism? Veganism is a way of living that seeks to exclude, as far as is possible and practicable, cruelty to and exploitation of animals. In dietary terms, this means avoiding eating animal products like meat, dairy, eggs and honey. Why Vegan? It’s better for animals! The majority of animals who are bred for consumption spend their short lives on a factory farm, before facing a terrifying death. Chickens like Bramble here spend their lives in tiny, windowless sheds. She had no access to natural light, fresh air, or even grass. Thankfully she was saved from slaughter. But many others aren’t as lucky. It helps the planet! Animal farming is responsible for more greenhouse gas emissions than all motorised transport combined. In addition, it is responsible for vast amounts of deforestation and water pollution around the world. The carbon footprint of a vegan diet is as much as 60% smaller than a meat-based one and 24% smaller than a vegetarian one. It’s healthy! You can obtain all of the nutrients your body needs from a vegan diet. As such, the British Dietetics Association and American Academy of Nutrition and Dietetics (along with many other similar organisations around the world) all support a well-planned vegan diet as being healthy and suitable for all age groups. Shopping It has never been easier to be vegan, with plant-based foods now available in every single supermarket. Thanks to Animal Aid’s #MarkItVegan campaign, the vast majority of supermarkets now clearly label their own-brand vegan products! Brands to look out for.. -

LJMU Research Online

LJMU Research Online Sparks, P and Brooman, SD Brexit: A New Dawn for Animals Used in Research, or a Threat to the ‘Most Stringent Regulatory System in the World’? A report on the development of a Brexit manifesto for Animals Used in Science. http://researchonline.ljmu.ac.uk/id/eprint/7632/ Article Citation (please note it is advisable to refer to the publisher’s version if you intend to cite from this work) Sparks, P and Brooman, SD (2017) Brexit: A New Dawn for Animals Used in Research, or a Threat to the ‘Most Stringent Regulatory System in the World’? A report on the development of a Brexit manifesto for Animals Used in Science. UK Journal of Animal Law, 1 (2). LJMU has developed LJMU Research Online for users to access the research output of the University more effectively. Copyright © and Moral Rights for the papers on this site are retained by the individual authors and/or other copyright owners. Users may download and/or print one copy of any article(s) in LJMU Research Online to facilitate their private study or for non-commercial research. You may not engage in further distribution of the material or use it for any profit-making activities or any commercial gain. The version presented here may differ from the published version or from the version of the record. Please see the repository URL above for details on accessing the published version and note that access may require a subscription. For more information please contact [email protected] http://researchonline.ljmu.ac.uk/ Brexit: A New Dawn for Animals Used in Research, or a Threat to the ‘Most Stringent Regulatory System in the World’? A report on the development of a Brexit manifesto for Animals Used in Science. -

![Henry Spira Papers [Finding Aid]. Library of Congress. [PDF Rendered](https://docslib.b-cdn.net/cover/0798/henry-spira-papers-finding-aid-library-of-congress-pdf-rendered-1020798.webp)

Henry Spira Papers [Finding Aid]. Library of Congress. [PDF Rendered

Henry Spira Papers A Finding Aid to the Collection in the Library of Congress Manuscript Division, Library of Congress Washington, D.C. 2017 Contact information: http://hdl.loc.gov/loc.mss/mss.contact Additional search options available at: http://hdl.loc.gov/loc.mss/eadmss.ms017017 LC Online Catalog record: http://lccn.loc.gov/mm00084743 Prepared by Colleen Benoit, Karen Linn Femia, Nate Scheible with the assistance of Jake Bozza Collection Summary Title: Henry Spira Papers Span Dates: 1906-2002 Bulk Dates: (bulk 1974-1998) ID No.: MSS84743 Creator: Spira, Henry, 1927-1998 Extent: 120,000 items; 340 containers plus 6 oversize ; 140 linear feet ; 114 digital files (3.838 GB) Language: Collection material in English Location: Manuscript Division, Library of Congress, Washington, D.C. Summary: Animal welfare advocate and political activist. Correspondence, writings, notes, newspaper clippings, advertisements, printed matter, and photographs, primarily relating to Spira's work in the animal welfare movement after 1974. Selected Search Terms The following terms have been used to index the description of this collection in the Library's online catalog. They are grouped by name of person or organization, by subject or location, and by occupation and listed alphabetically therein. People Douglas, William Henry James. Fitzgerald, Pegeen. Gitano, Henry, 1927-1998. Grandin, Temple. Kupferberg, Tuli. Rack, Leonard. Rowan, Andrew N. Singer, Peter, 1946- Singer, Peter, 1946- Ethics into action : Henry Spira and the animal rights movement. 1998. Spira, Henry, 1927-1998--Political and social views. Spira, Henry, 1927-1998. Trotsky, Leon, 1879-1940. Trull, Frankie. Trutt, Fran. Weiss, Myra Tanner. Organizations American Museum of Natural History. -

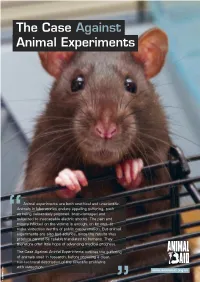

The Case Against Animal Experiments

The Case Against Animal Experiments Animal experiments are both unethical and unscientific. Animals in laboratories endure appalling suffering, such as being deliberately poisoned, brain-damaged and subjected to inescapable electric shocks. The pain and misery inflicted on the victims is enough, on its own, to make vivisection worthy of public condemnation. But animal “ “ experiments are also bad science, since the results they produce cannot be reliably translated to humans. They therefore offer little hope of advancing medical progress. The Case Against Animal Experiments outlines the suffering of animals used in research, before providing a clear, non-technical description of the scientific problems S E with vivisection. L I www.animalaid.org.uk C I N I M O D © How animals are used Contents Each year around four million How animals are used .......................... 1 animals are experimented on inside British laboratories. The suffering of animals in Dogs, cats, horses, monkeys, laboratories ........................................ 2 rats, rabbits and other animals Cruel experiments .................................... 2 are used, as well as hundreds A failing inspection regime ........................ 3 of thousands of genetically Secrecy and misinformation ...................... 4 modified mice. The most The GM mouse myth ................................ 4 common types of experiment The scientific case against either attempt to test how animal experiments .............................. 5 safe a substance is (toxicity Summary ............................................... -

31 March 2020 Vice-President Timmermans

. 31 March 2020 Vice-President Timmermans Please reply to: Commissioners Wojciechowski and Kyriakides European Commission Olga Kikou, B-1049 Brussels, Belgium Compassion in World Farming Place du Luxembourg 12, Marija Vučković Brussels B-1050, Belgium President of EU Agriculture Council Email: [email protected] Rue de la Loi 175 B-1048 Brussels, Belgium Dear President of the Agriculture Council, Commission Vice-President Timmermans, and Commissioners Kyriakides and Wojciechowski Export of live farm animals from EU to non-EU countries The letter sent to you on 19 March by 35 animal welfare organisations called, among other things, for the suspension of exports of live farm animals to non-EU countries. We are concerned that, despite this, these exports are continuing to take place. On 2 March the Croatian Presidency activated the EU Integrated Political Crisis Response Mechanism in full mode; since then at least 46 livestock vessels carrying EU animals have sailed to non-EU countries. Indeed, just since 27 March six livestock vessels have left EU ports for the Middle East and North Africa and another 17 are either inside EU ports or on their way to EU ports to load animals. As explained in the letter of 19 March, these journeys may contribute to the spread of COVID-19 among drivers, crew members, veterinarians, border officials, and port personnel loading and unloading animals. Crew members of ships arriving in the EU interact with EU port personnel during the loading of animals onto the ship; this can spread COVID-19 into the EU. Four livestock vessels have recently arrived in Romania from Saudi Arabia which has rising COVID-19 levels. -

Sorenson Interview with Ronnie

The Brock Review Volume 12 No. 1 (2011) © Brock University Interview with Ronnie Lee John Sorenson Ronnie Lee is widely-respected among activists as one of the founding members of the Animal Liberation Front (ALF) in the 1970s and for creating the now-discontinued magazine Arkangel in 1989. Lee joined the Hunt Saboteurs Association in the 1970s and in 1973 created another organization, the Band of Mercy (taking its name from the nineteenth-century anti-hunting youth groups organized by the RSPCA). The Band of Mercy was based on the idea of direct action, including the destruction of property used to harm animals, but its principles emphasized that no violence should be directed against humans. In 1974 Lee was sentenced to prison for rescuing animals from gruesome vivisection practices at the Oxford Animal Laboratory in Bicester; while in prison he was forced to go on a hunger strike to obtain vegan food. After being released from prison, Lee started the ALF, which operates under the following guidelines: • To liberate animals from places of abuse, i.e., laboratories, factory farms, fur farms, etc., and place them in good homes where they may live out their natural lives, free from suffering. • To inflict economic damage to those who profit from the misery and exploitation of animals. • To reveal the horror and atrocities committed against animals behind locked doors, by performing direct actions and liberations. • To take all necessary precautions against harming any animal, human and non-human. • Any group of people who are vegetarians or vegans and who carry out actions according to these guidelines have the right to regard themselves as part of the Animal Liberation Front.