Copyrighted Material

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

1 Assessment and Treatment of Sleep Disturbances Associated With

Dr. William Brim, Deputy Director, Center for Deployment Psychology Assessment and Treatment of Sleep Sleep and Insomnia Basics Disturbances Associated with Deployment Dr. William Brim “I’ll sleep when I’m dead Deputy DIrector ‐Warren Zevon 1 2 Why do we sleep? How is sleep regulated? Inactivity Theory • Also called an adaptive or evolutionary theory • Early scientists believed that gases rising • Sleep serves a survival function and has developed through natural selection • Animals that were able to stay out of harm’s way by being still and quiet during times of vulnerability, from the stomach during digestion brought usually at night…survived Energy Conservation on the transition to sleep. • Related to inactivity theory • Suggests primary function of sleep is to reduce energy demand and expenditure • Research has shown that energy metabolism is significantly reduced during sleep Restorative Aristotle (c350 B.C.) “We awaken when the • Sleep provides an opportunity for the body to repair and rejuvenate • Major restorative functions such as muscle growth, tissue repair, protein synthesis and growth hormone digestive process is complete” release occur mostly or exclusively during sleep Brain Plasticity • One of the most recent theories is based on findings that sleep is correlated to changes in the structure and organization of the brain. • Sleep plays a critical role in brain development with infants and children spending 12‐14 hours a day sleep and a link to adult brain plasticity is becoming clear as well 3 4 14-15 October 2014 1 How is sleep regulated? • Homeostatic sleep drive (Process S) – During wakefulness a drive for sleep builds up that is discharged primarily during sleep “Sleep is a dynamic behavior. -

Parasomnias: a Comprehensive Review

Open Access Review Article DOI: 10.7759/cureus.3807 Parasomnias: A Comprehensive Review Shantanu Singh 1 , Harleen Kaur 2 , Shivank Singh 3 , Imran Khawaja 1 1. Pulmonary Medicine, Marshall University School of Medicine, Huntington, USA 2. Neurology, Univeristy of Missouri, Columbia, USA 3. Internal Medicine, Maoming People's Hospital, Maoming, CHN Corresponding author: Harleen Kaur, [email protected] Abstract Parasomnias are a group of sleep disorders characterized by abnormal, unpleasant motor verbal or behavioral events that occur during sleep or wake to sleep transitions. Parasomnias can occur during non- rapid eye movement (NREM) and rapid eye movement (REM) stages of sleep and are more commonly seen in children than the adult population. Parasomnias can be distressful for the patient and their bed partners and most of the time, these complaints are brought up by their bed partners because of the possible disruption in their quality of sleep. As clinicians, it is crucial to understand the characteristics of various parasomnias and address them with detailed sleep history and essential diagnostic approach for proper evaluation. The review aims to highlight the epidemiology, pathophysiology and clinical features of various types of parasomnias along with the appropriate diagnostic and pharmacological approach. Categories: Internal Medicine, Neurology, Psychiatry Keywords: parasomnia, sleep walking, confusional arousals, sleep terror, nightmares, rem behavior disorder, sleep paralysis, rem parasomnias, nrem parasomnias Introduction And Background Parasomnias are a group of sleep disorders that are characterized by abnormal, unpleasant motor, verbal or behavioral events that occur during sleep or wake to sleep transitions [1]. The term ‘parasomnia’ was first coined by a French researcher Henri Roger in 1932 [2]. -

Sleep Disorders?”

Non-Respiratory Sleep Disorder Pearls Canadian Respiratory Conference April 16, 2016 Gosia Eve Phillips, MD Diplomate, American Board of Psychiatry and Neurology, Cert. Sleep Medicine Assistant Professor of Medicine, Division of Respirology, Dalhousie University Financial Interest Disclosure I have no conflict of interest. “I’m interested in breathing disorders… Why would I want to know about non-respiratory sleep disorders?” Why? Understand challenges in diagnosis and treatment of sleep apnea when comorbid sleep disorders are present Daytime symptoms may persist despite treatment of sleep apnea Identification and management of sleep disorders optimizes patient care Sleep Disorders Insomnia Circadian Rhythm Disorders Sleep Related Movement Disorders Hypersomnias of Central Origin Objectives Evaluation of sleep disorders Diagnostic tests Management of sleep disorders Evaluation Clinical History and Exam: Time course/ Precipitating factors Sleep-wake schedule Sleep-related phenomena, daytime symptoms Medical, psychiatric, substance history Sleep Studies Lab polysomnography Multiple Sleep Latency Test Ambulatory sleep study Insomnia Insomnia Sleep onset or maintenance insomnia Waking earlier than desired Despite adequate opportunity & circumstances for sleep Insomnia Symptoms fatigue or malaise attention, concentration, or memory impairment social or vocational dysfunction or poor school performance mood disturbance or irritability daytime sleepiness motivation, energy, or initiative reduction proneness for errors or accidents at work or while driving tension, headache, GI upset concerns about or dissatisfaction with sleep Insomnia - Tx Cognitive Behavioural Therapy (CBT) (standard): Cognitive: change pt’s beliefs & attitudes about insomnia e.g. attention shifting, decatastrophizing, reappraisal Behavioural: may include stimulus control tx, sleep restriction, relaxation training Sleep hygiene education: (insufficient evidence alone) health practices: diet, exercise, substance abuse environmental factors e.g. -

REM Sleep Behavior Disorder Dystonia Essential Tremor Isolated Sleep Paralysis Tourette Syndrome Hypnopompic Hallucinations Hemiballismus Complex Nocturnal Behaviors

Complex Nocturnal Behaviors Alon Y. Avidan MD, MPH Professor & Vice Chair, UCLA Department of Neurology Director, UCLA Sleep Disorders Center Michigan Academy Sleep Medicine (MASM) October 8th, 2016 FACULTY DISCLOSURES: In compliance with ACCME Standards for Commercial Support of CME activities… Alon Y. Avidan I have these relevant financial relationships to disclose: • Merck, Arbor Pharmaceuticals, Pernix: Consulting Fees, Honoraria. • AAN, AASM, CHEST, ACCP, ATS- Educational stipends. • Elsevier, LWW- Book Royalties. Complex Behaviors Around the 24 Clock Restless Legs Syndrome (RLS) Rhythmic Movement Disorders Hypnogogic Hallucinations Disorders of Seizures & RLS Arousal Cataplexy, (Non REM Psychogenic Spells Parasomnias) Nocturnal Seizures PRIMARILY IN WAKEFULNESS REM Nightmares & REDUCED IN REM-related Sleep apnea SLEEP Parkinson’s Disease (“PseudoRBD) Huntington’s Disease Myoclonus Ataxia REM Sleep Behavior Disorder Dystonia Essential Tremor Isolated Sleep Paralysis Tourette Syndrome Hypnopompic Hallucinations Hemiballismus Complex Nocturnal Behaviors Restless Legs Rhythmic Syndrome (RLS) Movement Disorders Disorders of Arousal (Non REM Parasomnias) Nocturnal Seizures REM Nightmares REM-related Sleep apnea (“PseudoRBD) REM Sleep Behavior Disorder Isolated Sleep Paralysis Parasomnias Disorders of Arousal (Non REM Parasomnias) [DDx Nocturnal Seizures] REM Nightmares REM Sleep Behavior Disorder Isolated Sleep Paralysis Sleep Related Movement Disorder Restless Legs Syndrome (RLS) Sleep Starts (Hypnic JerKs) Rhythmic Movement Disorders -

Sleep Disorders As Outlined by Outlined As Disorders Sleep of Classification N the Ribe the Features and Symptoms of Each Disorder

CHAPTER © Jones & Bartlett Learning, LLC © Jones & Bartlett Learning, LLC NOT FOR SALE OR DISTRIBUTION 2NOT FOR SALE OR DISTRIBUTION © Jones & Bartlett Learning, LLC © Jones & Bartlett Learning, LLC NOT FORSleep SALE OR DISTRIBUTION Disorders NOT FOR SALE OR DISTRIBUTION © Jones & Bartlett Learning, LLC © Jones & Bartlett Learning, LLC NOT FOR SALE OR DISTRIBUTION NOT FOR SALE OR DISTRIBUTION © Agsandrew/Shutterstock © Jones & Bartlett Learning, LLC © Jones & Bartlett Learning, LLC NOT FOR SALE OR DISTRIBUTION NOT FOR SALE OR DISTRIBUTION CHAPTER OUTLINE EEG arousal alveolar hypoventilation paradoxical breathing idiopathic central alveolar History of Sleep Disorders© Jones & Bartlett Learning, LLCmicrognathia © Joneshypoventilation & Bartlett Learning, LLC Classification of Sleep DisordersNOT FOR SALE OR DISTRIBUTIONretrognathia NOTsnoring FOR SALE OR DISTRIBUTION Insomnia apnea–hypopnea primary snoring Sleep-Related Breathing Disorders index (AHI) sleep-related groaning Central Disorders of Hypersomnolence respiratory disturbance catathrenia Circadian Rhythm Sleep–Wake Disorders index (RDI) CPAP therapy Parasomnias respiratory effort–related positional therapy Sleep-Related© Jones Movement & Bartlett Disorders Learning, LLC arousal (RERA)© Jones & Bartletttonsillectomy Learning, LLC OtherNOT Sleep FOR Disorders SALE OR DISTRIBUTION upper-airwayNOT resistance FOR SALEadenoidectomy OR DISTRIBUTION Chapter Summary syndrome bi-level therapy excessive daytime multiple sleep latency LEARNING OBJECTIVES sleepiness (EDS) test (MSLT) sudden infant -

Assessment and Treatment Analysis of Automatically Reinforced Behaviors: Examining the Relationship Between Physiological Responses and Aberrant Behaviors

Assessment and Treatment Analysis of Automatically Reinforced Behaviors: Examining the Relationship between Physiological Responses and Aberrant Behaviors by Nancy I. Salinas, M.A., BCBA, LBA A Dissertation In Special Education Submitted to the Graduate Faculty of Texas Tech University Partial Fulfillment of the Requirements for the Degree of DOCTOR OF PHILOSOPHY Approved Stacy L. Carter, Ph.D., BCBA-D Chair of Committee Robin H. Lock, Ph.D. Stephanie L. Hart, Ed.D., BCBA-D Mark Sheridan, Ph.D. Dean of Graduate School August, 2018 Copyright 2018 Nancy Salinas Texas Tech University, Nancy Salinas, August 2018 ACKNOWLEDGEMENTS I would like to thank Dr. Stacy Carter for his encouragement and support throughout the entire process of completing this dissertation. His keen advice helped to develop this study into a work that I can feel excited and proud of. I’m extremely grateful for having him as my committee chair and as someone I can always count on. I greatly appreciate the help from my thesis committee members, Dr. Robin Lock and Dr. Stephanie Hart. I am thankful to both of you for believing in my ability to accomplish this task. I also want to thank Erika Salinas, Claudia Goswitz, Jessica Matus, and Liz Tomko for facilitating various aspects of this study. Jacky and Angelique have been my inspiration and joy which has been instrumental for completing this endeavor. I am especially grateful to Shawn Happe for being the most patient and open-minded sounding board. Without his support, this project would not have come to fruition. Thank you! ii Texas Tech University, Nancy Salinas, August 2018 TABLE OF CONTENTS ACKNOWLEDGMENTS ........................................................................................................... -

Development and Evaluation of the Sleep Treatment and Education Program for Students (STEPS) Franklin Christian Brown

Louisiana Tech University Louisiana Tech Digital Commons Doctoral Dissertations Graduate School Fall 2002 Development and evaluation of the Sleep Treatment and Education Program for Students (STEPS) Franklin Christian Brown Follow this and additional works at: https://digitalcommons.latech.edu/dissertations Part of the Psychoanalysis and Psychotherapy Commons INFORMATION TO USERS This manuscript has been reproduced from the microfilm master. UMI films the text directly from the original or copy submitted. Thus, some thesis and dissertation copies are in typewriter face, while others may be from any type of computer printer. The quality of this reproduction is dependent upon the quality of the copy submitted.Broken or indistinct print, colored or poor quality illustrations and photographs, print bleedthrough, substandard margins, and improper alignment can adversely affect reproduction. In the unlikely event that the author did not send UMI a complete manuscript and there are missing pages, these will be noted. Also, if unauthorized copyright material had to be removed, a note will indicate the deletion. Oversize materials (e.g., maps, drawings, charts) are reproduced by sectioning the original, beginning at the upper left-hand comer and continuing from left to right in equal sections with small overlaps. ProQuest Information and Learning 300 North Zeeb Road, Ann Arbor, Ml 48106-1346 USA 800-521-0600 Reproduced with permission of the copyright owner. Further reproduction prohibited without permission. Reproduced with permission of the copyright owner. Further reproduction prohibited without permission. Development And Evaluation of the Sleep Treatment and Education Program for Students (STEPS) Franklin C. Brown, M.A. College of Education Louisiana Tech University A Dissertation Presented in Partial Fulfillment of the Requirements for the Degree Doctor of Philosophy November 2002 Reproduced with permission of the copyright owner. -

Clinician Guide — Narcolepsy in Pediatric Patients

CLINICIAN GUIDE Narcolepsy in Pediatric Patients A Practical Guide for Recognizing Narcolepsy Symptoms in Pediatric Patients 1 Narcolepsy Can Start in Childhood This brochure can help you: Table of Contents RECOGNIZE Narcolepsy in Pediatric Patients................................................... 4 Manifestations of the 5 main narcolepsy symptoms Narcolepsy Symptoms in Pediatric Patients............................. 5 in pediatric patients Recognizing Cataplexy...................................................................... 6 SCREEN Recognizing Hallucinations.............................................................. 8 Pediatric patients who present with excessive daytime sleepiness Recognizing Excessive Daytime Sleepiness.............................. 8 using a validated screening tool Recognizing Sleep Paralysis............................................................ 10 Recognizing Sleep Disruption........................................................ 10 Clinical Interview.............................................................................. 11 Clinical History and Symptom Assessment............................... 11 Questions to Ask During the Clinical Interview........................ 12 Differential Diagnosis...................................................................... 15 Distinguishing Narcolepsy From More Common Conditions... 15 Other Disorders............................................................................................. 18 Screening.......................................................................................... -

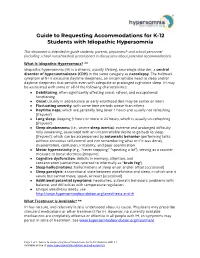

Guide to Requesting Accommodations for K-12 Students with Idiopathic Hypersomnia

Guide to Requesting Accommodations for K-12 Students with Idiopathic Hypersomnia This document is intended to guide students, parents, physicians* and school personnel (including school nurse/medical practitioner) in discussions about potential accommodations. What Is Idiopathic Hypersomnia? ** Idiopathic hypersomnia (IH) is a chronic, usually lifelong, neurologic disorder, a central disorder of hypersomnolence (CDH) in the same category as narcolepsy. The hallmark symptom of IH is excessive daytime sleepiness, an uncontrollable need to sleep and/or daytime sleepiness that persists even with adequate or prolonged nighttime sleep. IH may be associated with some or all of the following characteristics: ● Debilitating, often significantly affecting social, school, and occupational functioning ● Onset usually in adolescence or early adulthood (but may be earlier or later) ● Fluctuating severity, with some time periods worse than others ● Daytime naps, which are generally long (over 1 hour) and usually not refreshing [frequent] ● Long sleep: sleeping 9 hours or more in 24 hours, which is usually un-refreshing [frequent] ● Sleep drunkenness (i.e., severe sleep inertia): extreme and prolonged difficulty fully awakening, associated with an uncontrollable desire to go back to sleep [frequent], which can be accompanied by automatic behavior (performing tasks without conscious self-control and not remembering what or if it was done), disorientation, confusion, irritability, and poor coordination ● Motor hyperactivity (e.g., -

PE1281 Narcolepsy

Narcolepsy Narcolepsy appears to be a disorder of the part of the central nervous system that controls sleep and wakefulness. What is Narcolepsy is a chronic (lifelong) disorder that affects the brain and is narcolepsy? characterized by a permanent and overwhelming feeling of sleepiness. Narcolepsy affects many children, and most cases go undiagnosed and untreated. Although it is a relatively uncommon condition, its impact on a child’s life can be dramatic. It affects children of all genders equally, and symptoms usually develop after puberty, with most people reporting the first symptoms of narcolepsy between the ages of 15 and 30. What are the The symptoms of narcolepsy can appear all at once or they can develop symptoms of slowly over many years. The four most common symptoms are: narcolepsy? • Excessive daytime sleepiness. It is usually the first symptom of narcolepsy, Children with narcolepsy often report feeling tired all the time. They tend to fall asleep not only in situations in which many normal people feel sleepy (after meals or during a dull lecture), but also when most people would remain awake (while talking to someone or writing a letter). Individuals with narcolepsy may also fall asleep at dangerous times (like when driving a car). • Cataplexy. Cataplexy is the sudden, brief loss of muscle control triggered by a strong emotion, such as laughter, anger, or surprise. In children, cataplexy can also occur spontaneously. Cataplexy can range from subtle weakness in the face or slurred speech, to complete collapse. Cataplexy is sometimes the first symptom of narcolepsy but can also develop several years after daytime sleepiness. -

Automatic Behaviour in Individuals with Narcolepsy: a Qualitative Approach

AUTOMATIC BEHAVIOUR IN INDIVIDUALS WITH NARCOLEPSY: A QUALITATIVE APPROACH. By MICHELLE MORANDIN. Supervisor: Dorothy Bruck Submitted in partial fulfillment of the requirements for the degree of Doctor of Psychology (Clinical Neuropsychology) Victoria University Word count: 30, 095 words March, 2005. DECLARATION I certify that this thesis contains no material which has been accepted for the award of any other higher degree or graduate diploma in any university, and that to the best of my knowledge and belief the thesis contains no copy or paraphrase of material previously published or written by another person, except where due reference is made in the text of the thesis. Michelle Morandin ABSTRACT Narcolepsy is a debilitating sleep disorder, characterized by excessive daytime sleepiness, cataplexy, hypnogogic hallucinations, sleep paralysis and automatic behaviour. Automatic behaviour can be defined as “stereotyped and repetitive sequences of actions that are performed without awareness”, which usually occur during monotonous tasks (Zorick, Salis, Roth, & Kramer, 1979, p. 194). A classic example is reaching a destination without realizing how one got there. At present little is known about this complex phenomenon, and research in the area is minimal. The aim of the current study was to document the phenomenon of automatic behaviour in ten individuals with narcolepsy (selected on the basis of self-report of moderate to severe automatic behaviour), via phenomenological analysis and a series of case studies. Data was obtained through two structured interviews with each participant, an interview with a spouse or family member, a weekly journal and a daily journal (completed on minimal medication). Using qualitative methodology, a number of important features of automatic behaviour were identified. -

Daytime Sleepiness and Automatic Behavior Due to Severe

RESIDENT & FELLOW SECTION Teaching Video NeuroImages: Section Editor Daytime sleepiness and automatic behavior John J. Millichap, MD due to severe restless legs syndrome Anastasios Bonakis, MD A 76-year-old man complained of daytime sleepiness AUTHOR CONTRIBUTIONS Angeliki Konsta, MSci and frequent arousals from sleep due to a sense of Anastasios Bonakis: drafting the manuscript, study concept, analysis or Dimitris Dikeos, MD whole-body restlessness, followed by automatic fre- interpretation of data. Aggeliki Konsta: acquisition of data, interpretation of data. Dimitris Dikeos: drafting/revising the manuscript. quently injurious behavior. A video-polysomnography revealed periodic leg movements (figure) and arousal STUDY FUNDING Correspondence to followed by sleep episodes while standing, rhythmic No targeted funding reported. Dr. Bonakis: marching, and falling (videos 1 and 2 on the [email protected] DISCLOSURE Neurology® Web site at Neurology.org). A reevaluation The authors report no disclosures relevant to the manuscript. Go to of his history revealed symptoms compatible with rest- Neurology.org for full disclosures. less legs syndrome (RLS). Rotigotine1 proved very effec- tive, supporting the diagnosis of RLS. Periodic leg REFERENCES movement disorder leading to sleep-related rhythmic 1. Högl B, Oertel WH, Stiasny-Kolster K, et al. Treatment of movement disorder could also be considered. Auto- moderate to severe restless legs syndrome: 2-year safety and Supplemental data efficacy of rotigotine transdermal patch. BMC Neurol matic behavior denotes severe sleep deprivation2 and at Neurology.org 2010;10:86. may represent a non-REM parasomnia. Severe RLS 2. Guilleminault C, Billiard M, Montplaisir J, Dement WC. Download teaching slides: may present with automatic behavior complicating its Altered states of consciousness in disorders of daytime sleep- Neurology.org diagnosis.