PUBLIC BATH NO. 7, 227-231 Fourth Avenue, Borough of Brooklyn

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Installation of Trunk Water Mains Along Grand Street Project Phase I: Grand St

Manhattan September-October 2014 Installation of Trunk Water Mains Along Grand Street Project Phase I: Grand St. between Broadway and Bowery Phase II: Grand St. between Bowery and Essex St. Project # MED 609(606) The New York City Department of Design and Construction (NYCDDC) is managing a capital construction project MED609(606) along Grand Street between Broadway and Essex Street, including each intersection. DDC will install new trunk water mains, new traffic signs, street lighting, reconstruct distribution water mains, new roadway surface, curbs and sidewalks in certain locations, as well as, rehabilitate sewer, and upgrade private utilities. The entire project is anticipated to be completed by Spring 2017. Phase I of this project is scheduled to be completed by Fall 2014. Phase I final restoration has begun in April, 2014. Phase II is scheduled to begin in September, 2014. Work Completed to Date (Within Phase I Limits) 1. Curbs, Sidewalks & Roadway Have Been Replaced on Grand Street between Lafayette & Bowery 2. All Distribution Gas Mains Have Been Replaced (Over 2,000 feet) 3. All Distribution Water Mains Have Been Replaced (Over 2,000 feet) New Roadway with Street Markings on Grand Street between Centre Street & Centre Market Place 4. All 36” Trunk Water Main including Necessary Appurtenances Have Been Constructed (Over 2,000 feet) 5. Sewers in Need Have Been Rehabilitated or Replaced Special Needs (Approx. 500 feet) Individuals with special needs who may be uniquely impacted 6. Substandard Catch Basins (22) Have Been Replaced with by this project should contact the project’s Community Upgraded Structures for Improved Drainage Construction Liaison, as soon as possible, to make them 7. -

151 Canal Street, New York, NY

CHINATOWN NEW YORK NY 151 CANAL STREET AKA 75 BOWERY CONCEPTUAL RENDERING SPACE DETAILS LOCATION GROUND FLOOR Northeast corner of Bowery CANAL STREET SPACE 30 FT Ground Floor 2,600 SF Basement 2,600 SF 2,600 SF Sub-Basement 2,600 SF Total 7,800 SF Billboard Sign 400 SF FRONTAGE 30 FT on Canal Street POSSESSION BASEMENT Immediate SITE STATUS Formerly New York Music and Gifts NEIGHBORS 2,600 SF HSBC, First Republic Bank, TD Bank, Chase, AT&T, Citibank, East West Bank, Bank of America, Industrial and Commerce Bank of China, Chinatown Federal Bank, Abacus Federal Savings Bank, Dunkin’ Donuts, Subway and Capital One Bank COMMENTS Best available corner on Bowery in Chinatown Highest concentration of banks within 1/2 mile in North America, SUB-BASEMENT with billions of dollars in bank deposits New long-term stable ownership Space is in vanilla-box condition with an all-glass storefront 2,600 SF Highly visible billboard available above the building offered to the retail tenant at no additional charge Tremendous branding opportunity at the entrance to the Manhattan Bridge with over 75,000 vehicles per day All uses accepted Potential to combine Ground Floor with the Second Floor Ability to make the Basement a legal selling Lower Level 151151 C anCANALal Street STREET151 Canal Street NEW YORKNew Y |o rNYk, NY New York, NY August 2017 August 2017 AREA FINANCIAL INSTITUTIONS/BRANCH DEPOSITS SUFFOLK STREET CLINTON STREET ATTORNEY STREET NORFOLK STREET LUDLOW STREET ESSEX STREET SUFFOLK STREET CLINTON STREET ATTORNEY STREET NORFOLK STREET LEGEND LUDLOW -

NJDARM: Collection Guide

NJDARM: Collection Guide - NEW JERSEY STATE ARCHIVES COLLECTION GUIDE Record Group: Governor Franklin Murphy (1846-1920; served 1902-1905) Series: Correspondence, 1902-1905 Accession #: 1989.009, Unknown Series #: S3400001 Guide Date: 1987 (JK) Volume: 6 c.f. [12 boxes] Box 1 | Box 2 | Box 3 | Box 4 | Box 5 | Box 6 | Box 7 | Box 8 | Box 9 | Box 10 | Box 11 | Box 12 Contents Explanatory Note: All correspondence is either to or from the Governor's office unless otherwise stated. Box 1 1. Elections, 1901-1903. 2. Primary election reform, 1902-1903. 3. Requests for interviews, 1902-1904 (2 files). 4. Taxation, 1902-1904. 5. Miscellaneous bills before State Legislature and U.S. Congress, 1902 (2 files). 6. Letters of congratulation, 1902. 7. Acknowledgements to letters recommending government appointees, 1902. 8. Fish and game, 1902-1904 (3 files). 9. Tuberculosis Sanatorium Commission, 1902-1904. 10. Invitations to various functions, April - July 1904. 11. Requests for Governor's autograph and photograph, 1902-1904. 12. Princeton Battle Monument, 1902-1904. 13. Forestry, 1901-1905. 14. Estate of Imlay Clark(e), 1902. 15. Correspondence re: railroad passes & telegraph stamps, 1902-1903. 16. Delinquent Corporations, 1901-1905 (2 files). 17. Robert H. McCarter, Attorney General, 1903-1904. 18. New Jersey Reformatories, 1902-1904 (6 files). Box 2 19. Reappointment of Minister Powell to Haiti, 1901-1902. 20. Corporations and charters, 1902-1904. 21. Miscellaneous complaint letters, December 1901-1902. file:///M|/highpoint/webdocs/state/darm/darm2011/guides/guides%20for%20pdf/s3400001.html[5/16/2011 9:33:48 AM] NJDARM: Collection Guide - 22. Joshua E. -

GRADUATES of NACHES VALLEY HIGH SCHOOL Class of 1917 - 1924 Naches, Yakima County, Washington

GRADUATES OF NACHES VALLEY HIGH SCHOOL Class of 1917 - 1924 Naches, Yakima County, Washington Class of 1917 (First Graduating Class) Willard McKinley Sedge (15 February 1897 - 22 August 1972) Born and raised in Naches, after graduation he attended Washington State College. When he returned he married Marjorie A. Knickrehn (Lower Naches Class of 1919) on November 13, 1925. Willard was the youngest child of Henry and Sarah Elnore (Plumley) Sedge. He had six siblings, four sisters and two brothers. He and Marjorie had no children. Willard owned and operated a fruit ranch in Naches until the time of his death. Class of 1918 Harry Andrew Brown (10 May 1900 - 28 February 1998) Born in Genesee County, New York to Seth and Anna (Troseth) Brown, after graduation Harry attended Washington State College. He was the third son in a family of four boys and two girls. He and his family moved to Naches between 1905 and 1910. Harry married Elizabeth Ann McInnis on September 2, 1938. After her death in 1956 he met and married Lolita J. Lapp Saar on March 10, 1960. Marion Lewis Clark (15 November 1898 - 13 April 1979) Born and raised in Naches, Marion was the youngest son of William Samuel Clark and Elizabeth Ann Kincaid. He continued his education at Washington State College. Marion married Alice Frances Selde on June 5, 1927 in Lincoln County, Washington and together they built and developed an orchard home in the Naches Valley. Jean C. McIver (3 January 1901 - 27 January 1996) Jean taught one year in Naches, worked in a bank in Hoquiam and then, after marrying Roy M. -

Finding Aid for the Andrew Brown &

University of Mississippi eGrove Archives & Special Collections: Finding Aids Library November 2020 Finding Aid for the Andrew Brown & Son - R.F. Learned Lumber Company/Lumber Archives (MUM00046) Follow this and additional works at: https://egrove.olemiss.edu/finding_aids Recommended Citation Andrew Brown & Son - R.F. Learned Lumber Company/Lumber Archives (MUM00046). Archives and Special Collections, J.D. Williams Library, University of Mississippi. This Finding Aid is brought to you for free and open access by the Library at eGrove. It has been accepted for inclusion in Archives & Special Collections: Finding Aids by an authorized administrator of eGrove. For more information, please contact [email protected]. University of Mississippi Libraries Andrew Brown & Son - R.F. Learned Lumber Company/Lumber Archives MUM00046 TABLE OF CONTENTS ACCESS RESTRICTIONS Summary Information Open for research. This collection is stored at an off- site facility. Researchers interested in using this Historical Note collection must contact Archives and Special Collections at least five business days in advance of Scope and Contents Note their planned visit. Administrative Information Return to Table of Contents » Access Restrictions Collection Inventory Series 1: Brown SUMMARY INFORMATION Correspondence. Series 2: Brown Business Repository Records. University of Mississippi Libraries Series 3: Learned ID Correspondence. MUM00046 Series 4: Learned Business Records. Date 1837-1974 Series 5: Miscellaneous Series. Extent 117.0 boxes Series 6: Natchez Ice Company. Abstract Series 7: Learned Collection consists of correspondence, business Plantations records, various account books and journals, Correspondence. photographs, pamphlets, and reports related to the Andrew Brown (and Son), and its immediate successor Series 8: Learned company, R.F. -

Trinity College Bulletin, 1941-1942 (Necrology)

Trinity College Trinity College Digital Repository Trinity College Bulletins and Catalogues (1824 - Trinity Publications (Newspapers, Yearbooks, present) Catalogs, etc.) 7-1-1942 Trinity College Bulletin, 1941-1942 (Necrology) Trinity College Follow this and additional works at: https://digitalrepository.trincoll.edu/bulletin Recommended Citation Trinity College, "Trinity College Bulletin, 1941-1942 (Necrology)" (1942). Trinity College Bulletins and Catalogues (1824 - present). 126. https://digitalrepository.trincoll.edu/bulletin/126 This Book is brought to you for free and open access by the Trinity Publications (Newspapers, Yearbooks, Catalogs, etc.) at Trinity College Digital Repository. It has been accepted for inclusion in Trinity College Bulletins and Catalogues (1824 - present) by an authorized administrator of Trinity College Digital Repository. OLUME XXXIX NEW SERIES NUMBER 3 Wriutty <trnllrgr iullrtiu NECROLOGY Jlartforb, C!tounrdtrut July, 1942 Trinity College Bulletin Issued quarterly by the College. Entered January 12, 1904, at Hartford, Conn., as second class matter under the Act of Congress of July 16, 1894. Accepted for mailing at special rate of postage provided for in Section 1103, A ct of October 3, 1917, authorized March J, 1919. The Bulletin includes in its issues: The College Catalogue; Reports of the President. Treasurer. Dean. and Librarian; Announcements, Necrology, and Circulars of Information. NECROLOGY TRINITY MEN Whose deaths were reported during the year 1941-1942 Hartford, Connecticut July, 1942 PREFATORY NOTE This Obituary Record is the twenty-second issued, the plan of devoting the July issue of the Bulletin to this use having been adopted in 1918. The data here presented have ·been collected through the persistent efforts of the Treasurer's Office, _which makes every effort to secure and preserve as full a record as possible of the activities of Trinity men as well as anything else . -

The Development of Sanitation and Sanitary Engineering

Mcknight Development of Sanitation And Sanitary Engineering Mun. & San. Engineering B. | 1904 m * i 1 • • OTJVEKSVIT OF 11,1. LIBRAE* • * . * # ^ ^ ^ ^ UNIVERSITY OF ILLINOIS LIBRARY BOOK CLASS VOLUME * * * # f * # #1 bfc\Wkm\ * * # * 1 ir * * * * 4 m[\ * IK * * * + # * * f * * # * * . * * * * v ffS| * ^ X*- ^ * jfr P If* mm m m * * * mm * # * * * * * * * 16 m # * 4 # P * * # * * mm * ' * * * # * # * * * # * I # * # # & ^ * #- # * * # 4 m II ife 4 *' * * i ^ f * * 4 # ii # * # - # # n6 . # * ^ ^ . 4 # fc # # * ^ * # ^ ^ # 31 THE DEVELOPMENT OP SANITATION AND SANITARY ENGINEERING ...BY... William Asbury McKnight THESIS FOR THE DEGREE OF BACHELOR OF SCIENCE IN MUNICIPAL AND SANITARY ENGINEERING COLLEGE OF ENGINEERING UNIVERSITY OF ILLINOIS PRESENTED JUNE, 1904 . UNIVERSITY OH ILLINOIS May 27, 1904 I !H> THIS IS TO CERTIFY THAT THE THESIS PREPARED UNDER MY SUPERVISION BY william asbury Mcknight entitled THE MlEh Q.P.ME NT... - OF S.ANITAT ION and SANITARY. ENGI NEERI NG IS APPROVED BY MB AS FULFILLING THIS PART OF THE REQUIREMENTS FOR THE DEGREE OF Bachelor of Science in Municipal & Sanitary ring Enginee ; HEAD OF DEPARTMENT OF 66160 THE DEVELOPMENT OF SANITATION AND SANITARY ENGINEERING Sanitation and sanitary engineering involves the construc- tion and maintenance of works, methods of water and sewage purification, the improvement and control of conditions in cities, etc., by which the public health of communities and nations is promoted and disease prevented. The importance of the science is apparent. The truths which form the basis" of sanitary science have been discovered by the medical profes- sion, scientists, boards of health, and sanitary engineers. In almost all classes of society there is a great and growing interest in sanitation. -

A Big Bet on Game-Changing ADHD Treatment

20131202-NEWS--0001-NAT-CCI-CN_-- 11/27/2013 4:21 PM Page 1 CRAIN’S® NEW YORK BUSINESS VOL. XXIX, NO. 48 WWW.CRAINSNEWYORK.COM DECEMBER 2-8, 2013 PRICE: $3.00 Ice,Ice, ice,ice, maybemaybe Now-or-never vote on Bronx GOAL: Ice center CEO and hockey legend armory rink plan Mark Messier says the $275 million complex tests new norms will reap economic for development benefits for the Bronx. BY THORNTON MCENERY If there is one word in real estate circles that conveys the new poli- tics of commercial development in New York, it is Kingsbridge. The name of a long-shuttered Bronx armory, it connotes a semi- nal moment in the annals of city projects. Just as the failed Westway highway proposal of the 1970s and ’80s showed the power of environ- mentalism to kill a project, Kings- bridge did so for the cause of so- called living-wage jobs. In two weeks, almost four years to the day after a mall planned for the cavernous armory was defeat- ed by Bronx politicians, the final chapter in the Kingsbridge politi- cal saga is expected to be written. Having rejected the mall plan for See KINGSBRIDGE on Page 45 buck ennis A big bet on game-changing ADHD treatment deluxe version that will be released heart and lungs. the game,with a control group,is set Brain-to-computer interface tracks kids’ commercially for 8- to That,at least,is the idea.The chil- to begin on the Upper West Side focus; clinical study in city set to launch 12-year-olds next sum- dren, who play for 20 minutes with children at the Hallowell Cen- mer by Waltham,Mass.- three times a week,are part of ter, which specializes in treating at- based startup Atentiv. -

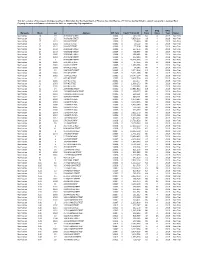

2019 Non Filers Manhattan

This list consists of income-producing properties in Manhattan that the Department of Finance has identified as of 7/1/20 as having failed to submit a properly completed Real Property Income and Expense statement for 2019 as required by City regulations. Tax Bldg. RPIE Borough Block Lot Address ZIP Code Final FY19/20 AV Class Class Year Status Manhattan 10 19 25 BRIDGE STREET 10004 $ 749,700 K2 4 2019 NonFiler Manhattan 11 15 70 BROAD STREET 10004 $ 4,859,100 O8 4 2019 NonFiler Manhattan 17 1213 50 WEST STREET 10006 $ 70,450 RB 4 2019 NonFiler Manhattan 17 1214 50 WEST STREET 10006 $ 59,550 RB 4 2019 NonFiler Manhattan 17 1215 50 WEST STREET 10006 $ 77,908 RB 4 2019 NonFiler Manhattan 24 1168 40 BROAD STREET 10004 $ 627,373 RB 4 2019 NonFiler Manhattan 24 1172 40 BROAD STREET 10004 $ 498,946 RB 4 2019 NonFiler Manhattan 25 1002 25 BROAD STREET 10004 $ 386,480 RK 4 2019 NonFiler Manhattan 25 1003 25 BROAD STREET 10004 $ 532,444 RK 4 2019 NonFiler Manhattan 29 1 85 BROAD STREET 10004 $ 98,500,050 O4 4 2019 NonFiler Manhattan 29 1301 54 STONE STREET 10004 $ 47,366 R8 2C 2019 NonFiler Manhattan 33 1001 99 WALL STREET 10005 $ 1,059,455 RK 4 2019 NonFiler Manhattan 33 1003 99 WALL STREET 10005 $ 64,346 RK 4 2019 NonFiler Manhattan 37 13 129 FRONT STREET 10005 $ 3,574,800 H3 4 2019 NonFiler Manhattan 40 1001 73 PINE STREET 10005 $ 5,371,786 RB 4 2019 NonFiler Manhattan 40 1002 72 WALL STREET 10005 $ 14,747,264 RB 4 2019 NonFiler Manhattan 41 15 60 PINE STREET 10005 $ 3,602,700 H5 4 2019 NonFiler Manhattan 41 1001 50 PINE STREET 10005 $ 233,177 -

Chinatown Little Italy Hd Nrn Final

NPS Form 10-900 OMB No. 10024-0018 (Oct. 1990) United States Department of the Interior National Park Service National Register of Historic Places Registration Form This form is for use in nominating or requesting determinations for individual properties and districts. See instructions in How to Complete the National Register of Historic Places Registration Form (National Register Bulletin 16A). Complete each item by marking “x” in the appropriate box or by entering the information requested. If an item does not apply to the property being documented, enter “N/A” for “not applicable.” For functions, architectural classification, materials, and areas of significance, enter only categories and subcategories from the instructions. Place additional entries and narrative items on continuation sheets (NPS Form 10-900a). Use a typewriter, word processor, or computer to complete all items. 1. Name of Property historic name Chinatown and Little Italy Historic District other names/site number 2. Location Roughly bounded by Baxter St., Centre St., Cleveland Pl. & Lafayette St. to the west; Jersey St. & street & number East Houston to the north; Elizabeth St. to the east; & Worth Street to the south. [ ] not for publication (see Bldg. List in Section 7 for specific addresses) city or town New York [ ] vicinity state New York code NY county New York code 061 zip code 10012 & 10013 3. State/Federal Agency Certification As the designated authority under the National Historic Preservation Act, as amended, I hereby certify that this [X] nomination [ ] request for determination of eligibility meets the documentation standards for registering properties in the National Register of Historic Places and meets the procedural and professional requirements as set forth in 36 CFR Part 60. -

Being Margaret Haley, Chicago, 1903

Being Margaret Haley, Chicago, 1903 By Kate Rousmaniere Key note address: International Standing Conference for the History of Education, July 12, 2001, Birmingham, England. To be published in Paedagogical Historica, (March, 2003). As I consider the question of “The City as a Light and Beacon?”—the leading question of this International Standing Conference on the History of Education in Birmingham—I keep wondering what it means to live in a city, both in my own experience, and in the experience of my biography subject, Margaret Haley, a woman teacher union leader who lived and worked in a great American city—Chicago—one hundred years ago.1 I am thinking partly about the material things that cities have always offered women – things like work, culture, anonymity and social freedom -- but I am also thinking about cities and how they can shape identity. Living in a city allows people to re-create themselves. The attraction of a city is not merely the physical experience, or the fact that there are quantitatively more things to do there than in a small village, but it is also the way that cities allow a change in a person’s way of being. In my own experience, city life has been like a particular relationship that I have had with another side of myself. I feel different when I’m in a city. My pulse 1 For help with this paper, I thank Marna Suarez, Tom Poetter, Wright Gwyn, John Bercaw, and Jessie Rousmaniere. I am grateful also to Ian Grosvenor and Ruth Watts for inviting me to present this keynote address. -

Former Police Headquarters Building Serves As an I Mp Ort Ant Reminder of the Police Department's Proud History

Landmarks Preservation Commission September 26, 1978, Designation List LP-0999 FORMER FOLIC E HEADQUARTERS BUILDING, 240 Centre Street, Borough of Manhattan. Built 1905-1909; architects Hoppin, Koen and Huntington~ Landmark Site: Borough of Manhattan Tax Map Block lt72, Lot 31. On July 11, 1978, the Landmarks Preservation Commission held a public hearing on the proposed designation as a Landmark of the Former Fblice Headquarters Building and the proposed designation of the related Landmark Site (Item No .3). The building had been hears previously in 1966, 1970 and 1974. The hearing had been duly advertised in accondance with the provisions of law. Seven witnesses spoke in favor of designation. There were no speakers in opposition to designation. DESCRIPI'ION .AND .ANALYSIS Designed by the architectural firm of Hoppin and Koen, the former New York City Fblice Headquarters building at 240 Centre Street was built between 1905 and 1909 and stands today as one of New York City's most important examples of the Edwardian Baroque style and of the Beaux-Arts principles of design. On May 6, 1905, Mayor George B. McClellan, amid the ceremony of a police band and mounted troops, wielded a silver trowel to lay the cornerstone of the building which was hailed by the press as the most up-to-date of its kind in the world. 1 Since the establishment of the first police office at City Hall in 1798 when "to facilitate the apprehension of criminals" an effort was made to supplement the traditional night watch, 2 the New York Fblice Department had witnessed the uneasy growth of the nation 's largest city.