(LIFT)/ UNOPS Dry Zone Program Inception Mission 14-30 October

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Annex 3 Public Map of Rakhine State

ICC-01/19-7-Anx3 04-07-2019 1/2 RH PT Annex 3 Public Map of Rakhine State (Source: Myanmar Information Management Unit) http://themimu.info/sites/themimu.info/files/documents/State_Map_D istrict_Rakhine_MIMU764v04_23Oct2017_A4.pdf ICC-01/19-7-Anx3 04-07-2019 2/2 RH PT Myanmar Information Management Unit District Map - Rakhine State 92° EBANGLADESH 93° E 94° E 95° E Pauk !( Kyaukhtu INDIA Mindat Pakokku Paletwa CHINA Maungdaw !( Samee Ü Taungpyoletwea Nyaung-U !( Kanpetlet Ngathayouk CHIN STATE Saw Bagan !( Buthidaung !( Maungdaw District 21° N THAILAND 21° N SeikphyuChauk Buthidaung Kyauktaw Kyauktaw Kyaukpadaung Maungdaw Mrauk-U Salin Rathedaung Mrauk-U Minbya Rathedaung Ponnagyun Mrauk-U District Sidoktaya Yenangyaung Minbya Pwintbyu Sittwe DistrictPonnagyun Pauktaw Sittwe Saku !( Minbu Pauktaw .! Ngape .! Sittwe Myebon Ann Magway Myebon 20° N RAKHINE STATE Minhla 20° N Ann MAGWAY REGION Sinbaungwe Kyaukpyu District Kyaukpyu Ma-Ei Kyaukpyu !( Mindon Ramree Toungup Ramree Kamma 19° N 19° N Bay of Bengal Munaung Toungup Munaung Padaung Thandwe District BAGO REGION Thandwe Thandwe Kyangin Legend .! State/Region Capital Main Town !( Other Town Kyeintali !( 18° N Coast Line 18° N Map ID: MIMU764v04 Township Boundary Creation Date: 23 October 2017.A4 State/Region Boundary Projection/Datum: Geographic/WGS84 International Boundary Data Sources: MIMU Gwa Base Map: MIMU Road Boundaries: MIMU/WFP Kyaukpyu Place Name: Ministry of Home Affairs (GAD) Gwa translated by MIMU Maungdaw Mrauk-U Email: [email protected] Website: www.themimu.info Sittwe Ngathaingchaung Copyright © Myanmar Information Management Unit Kilometers !( Thandwe 2017. May be used free of charge with attribution. 0 15 30 60 Yegyi 92° E 93° E 94° E 95° E Disclaimer: The names shown and the boundaries used on this map do not imply official endorsement or acceptance by the United Nations.. -

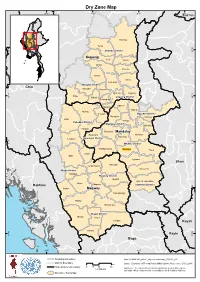

Dry Zone Map

Dry Zone Map 94°E 95°E 96°E Kachin97°E Kanbalu Ta S ei Shwebo District 23°N 23°N Sagaing Ye-U Khin-U Tabayin Shwebo Butalin Wetlet A Ya Daw Monywa District Chin Yinmabin Monywa Myin Mu Sagaing Palae 22°N Salingyi Sagaing District 22°N Chaung Oo Ngazun Myaung Tada-U Myaing Yesagyo Kyaukse District Myingyan Kyaukse Pauk Natogyi Pakokku District Myingyan District Myitthar Pakkoku Taungthar Mandalay Nyaung-U Wundwin Mahlaing Seikphyu Nyaung-U District 21°N Meiktila District 21°N Kyaukpadaung Meikhtila Tharzi Chauk Salin Pyawbwe Shan Natmauk Yenanchaung Yamaethin Minbu District Pwintbyu Magway District Myothit Nay Pyi Taw-Tatkon Minbu Rakhine Magway Yamethin District Ngape 20°N Magway 20°N Taungdwingyi Minhla Sinbaungwe Thayet District Mindon Thayet Aunglan Kayah Kanma Kayin 19°N 19°N Bago 94°E 95°E 96°E 97°E Township Boundary Map ID: MIMU163_ADPC_DryZoneTownships_090601_v02 District Boundary km Source: Boundary: WFP modified by MIMU (2008); Place name: GAD (2008) 0306015 State/Division Boundary Disclaimer: The names shown and designations used on this map do 1:2,300,000 not imply official endorsement or acceptance by the United Nations. Dry Zone Townships Myanmar Information Management Unit Meiktila Township - Mandalay Region 95°30'E 95°35'E 95°40'E 95°45'E 95°50'E 95°55'E 96°0'E 96°5'E TAUNGTHA Nyaung Zauk (193942) N WUNDWIN N ' ' 0 (Nyaung Zauk) 0 ° Shar Taw Ywar Thit (193950) ° 1 1 2 Nyaung Pin Thar (193943) (Nyaung Zauk) Nga Set Kan (193918) 2 BHUTAN (Nyaung Zauk) (Se Kone) Chon Sun (193917) (Se Kone) Taung Kone (193944) Se Kone (193916) -

Village Tracts of Saw Township Magway Region

Myanmar Information Management Unit Village Tracts of Saw Township Magway Region 94°0’E 94°10’E 94°20’E 94°30’E Pein Hne Kyee Ywar Thar 21°30’N 21°30’N Hnaw Ta Py in Mi Ae Ah Nyar Pan Pa Lun Pauk Nwar Thoe San Nga Lun Pin Taung Ta w Kh a L un Pan San Kyaukhtu Myauk Ma Kyin Ta y Min Kyi Ah Neint Man Kan Mindat Gyi Lay Yint Let Pan Yae Ye Pa Soke Shin Taunt Te t Yaw Kun Khin Kyan Taw 21°20’N Kyauk Leik 21°20’N Let Mun Kan Chaung Hnget Chaung Nyaung Gan Tha Lel Khwin Chaung Kyin Lein SAW Ah Nyar Ka Tin Kanpetlet Yaw Let Pan Lel Yin Kya Khat 21°10’N Saw 21°10’N Urban Kyauk Swea Thee Kone Lel Hpyu Hlaw Kar Yint Ye Chaung Taung Kyun Taw Boet Gyi Poke Pa Kaing Yin Ke Laung Shey In Bu Si Mee 21°0’N 21°0’N Swea Lwea Kyin Pein Chaung Nyaung Pin Pauk Pan Saing Kyein Gyi Sagaing Nga Lel Khon Tint Tu Chin Yan Shan Taung Nga Kut Hnget Mandalay Pyar Kyin Magway Bay of Bengal Rakhine Pale Bago Kilometers 0482 Ayeyarwady 20°50’N 20°50’N 94°0’E 94°10’E 94°20’E 94°30’E Map ID: MIMU575v01 Legend Data Sources : GLIDE Number: TC-2010-000211-MMR Cyclone BASE MAP - MIMU State Capital Road Village Tract Boundaries Creation Date: 6 December 2010. A3 Boundaries - WFP/MIMU/UNICEF Township Boundary Cyclone Path Projection/Datum: Geographic/WGS84 Main Town Place names - Ministry of Home Affair District Boundary Other Town (GAD) translated by MIMU State Boundary Map produced by the MIMU - [email protected] Website : http://www.themimu.info Disclaimer: The names shown and the boundaries used on this map do not imply official endorsement or acceptance by the United Nations.. -

Myanmar Myanma Economic Bank (MEB)

Maybank Money Express (MME) Agent - Myanmar Myanma Economic Bank (MEB) Branch Location Last Update: 08/10/2012 NO NAME OF AGENT City Region / Province Address Contact Number Operating Hour 067-421314 1 NAY PYI TAW NAYPYITAW NAYPYITAW 26,ThiraKyawswar Road, NAY PYI TAW. 9:30am-3:00pm 067-421532 067-22057 2 PYIN MA NAR PYINMANAR NAYPYITAW 10, (6) St, Shwe Chi Quarter,PYIN MA NAR. 9:30am-3:00pm 067-26830 3 TAT KONE TAT KONE NAYPYITAW SipinTharyaryay St,Myawaddy Quarter,Tatkone 067-71093 9:30am-3:00pm 4 LAWAY LAWAY NAYPYITAW Yone St, (6)Quarter, LAWAY 067-30348 9:30am-3:00pm 5 MAGWAY MAGWAY MAGWAY 9-E,Kanthar 14 St,Soe Kawmin Quarter,Magway 063-23311 9:30am-3:00pm Lanmataw St,Shwebonethar Yat,Thittapwe 6 YENANGYAUNG YENANGYAG MAGWAY 061-21709 9:30am-3:00pm Quarter, YENANGYAUNG 7 CHAUK CHAUK MAGWAY (15)Quarter,Myaynigone Yat, CHAUK. 061-200219 9:30am-3:00pm 8 TAUNGDWINGYI TGDWINGYI MAGWAY Bogyoke St,Taungpyin(2)Quarter,Taungdwinkyi 063-50276 9:30am-3:00pm 9 MYOTHIT MYOTHIT MAGWAY Min Quarter, MYOTHIT. 063-53002 9:30am-3:00pm Natmauk-Pyawbwe Road,Market Quarter, 10 NATMAUK NATMAUK MAGWAY 063-69691 9:30am-3:00pm NATMAUK 068-21434 11 THAYET THAYET MAGWAY 2,Corner of ThanKyo St & Merchant St,THAYET. 9:30am-3:00pm 068-21435 12 AUNG LAN AUNG LAN MAGWAY Aunglan-pyay Road,Satyone Quarter,AUNG LAN 069-201180 9:30am-3:00pm 13 MINHLA MINHLA MAGWAY Anawyahtar St,(5)Quarter,MINHLA 065-45424 9:30am-3:00pm 14 SINBAUNGWE SINBAUNGWE MAGWAY 238, (1)Quarter, SINBAUNGWE 069-40046 9:30am-3:00pm 068-50066 15 KANMA KANMA MAGWAY (3)Quarter, KANMA. -

Village Tracts of Thayet Township Magway Region

Myanmar Information Management Unit Village Tracts of Thayet Township Magway Region 94°54’E 95°0’E 95°6’E 95°12’E Nyaung Ywar Nge Ta t Moe Nat Kone Gon Ma Ni Shwe Pan Kaing Htee Yoe Baw Kyar Kan Inn Lel 19°30’N 19°30’N Tha Yet Myint Pauk Taw Ah Lat Lel Sin Thay Pun Gyi Myauk Kyut Yae Bwet Kya U Oke Shit Kone San Lel Kun Ohn Taw Myin Thar Mya Sa Kaing Ohn Mun Taw Ban Pyin Nyaung Zit Nga Hlaing Chon 19°24’N 19°24’N Pay Ka Tin Hman Din Gyi THAYET Let Pan Seik Pi Tauk Pin Yae Myet Yae Hpyu Kyauk Oe San Aint Koe Pin Inn Ma Nge Ta La Par Urban Thayet Yae Paw Ban Kone Pyin Htaung Kyun Min Te 19°18’N 19°18’N Htone Taung Twin Lel Pyin Aing Peik Tha Lein Pauk U Kar Sin Kaw To n Pon Nar Sagaing Pya Yae Gyoe Gyar Chin 19°12’N 19°12’N Shan Mandalay Ywar Ma Par Put Magway Bay of Bengal Rakhine Bago Kilometers 0241 Ayeyarwady 94°54’E 95°0’E 95°6’E 95°12’E Map ID: MIMU575v01 Legend Data Sources : GLIDE Number: TC-2010-000211-MMR Cyclone BASE MAP - MIMU State Capital Road Village Tract Boundaries Creation Date: 3 December 2010. A3 Boundaries - WFP/MIMU/UNICEF Township Boundary Cyclone Path Projection/Datum: Geographic/WGS84 Main Town Place names - Ministry of Home Affair District Boundary Other Town (GAD) translated by MIMU State Boundary Map produced by the MIMU - [email protected] Website : http://www.themimu.info Disclaimer: The names shown and the boundaries used on this map do not imply official endorsement or acceptance by the United Nations.. -

PACT Diesel Minigrid Study10

Enabling Electricity Access in Myanmar Diesel Mini Grid Assessment, november 2016 U Kyaw Thu comes home at 6pm a2er spending the day at his farm growing lenls and sesame. A diesel engine starts growling in the background and the street lamps light up. Some of his friends and neighbors switch on their television sets while the children open their books to make best use of these 2 hours before the village plunges into darkness. Aer 9pm, while the village prepares to sleep and the diesel engine stops, children light up candles in their homes to study for another few hours so that they do not have to spend their lives being farmers in this darkness of these villages in Myanmar. Through this assessment, Pact Myanmar seeks to understand the struggle, needs, ingenuity and outlook of villagers seeking to gain access to electricity in Myanmar and who have established diesel mini grids in their villages. We explore U Kyaw Thu’s village, Kone, which lies in Seikphyu Towhship and another 9 villages in Magway Region to understand how the village community has collaborated to establish basic electrifica:on and whether there could be ways to improve the systems and provide electricity for not only ligh:ng but also produc:ve use, which could accelerate the overall village development. Mandalay Yoma About Pact Myanmar Pact Myanmar’s programming aims to fundamentally improve people’s lives to affect positive material impact on Myanmar’s development. We do this by operating simultaneously at scale and at the village level to maximize impact. We believe passionately in community involvement in designing solutions to everyday problems. -

Administrative Map

Myanmar Information Management Unit Myanmar Administrative Map 94°E 96°E 98°E 100°E India China Bhutan Bangladesh Along India Vietnam KACHIN Myanmar Dong Laos South China Sea Bay of Bengal / Passighat China Thailand Daporija Masheng SAGAING 28°N Andaman Sea Philippines Tezu 28°N Cambodia Sea of the Philippine Gulf of Thailand Bangladesh Pannandin !( Gongshan CHIN NAWNGMUN Sulu Sea Namsai Township SHAN MANDALAY Brunei Malaysia Nawngmun MAGWAY Laos Tinsukia !( Dibrugarh NAY PYI TAW India Ocean RAKHINE Singapore Digboi Lamadi KAYAH o Taipi Duidam (! !( Machanbaw BAGO Margherita Puta-O !( Bomdi La !( PaPannssaauunngg North Lakhimpur KHAUNGLANHPU Weixi Bay of Bengal Township Itanagar PUTA-O MACHANBAW Indonesia Township Township Thailand YAN GON KAY IN r Khaunglanhpu e !( AYE YARWADY MON v Khonsa i Nanyun R Timor Sea (! Gulf of Sibsagar a Martaban k Fugong H i l NANYUN a Township Don Hee M !( Jorhat Mon Andaman Sea !(Shin Bway Yang r Tezpur e TANAI v i TANINTHARYI NNaaggaa Township R Sumprabum !( a Golaghat k SSeellff--AAddmmiinniisstteerreedd ZZoonnee SUMPRABUM Township i H Gulf of a m Thailand Myanmar administrative Structure N Bejiang Mangaldai TSAWLAW LAHE !( Tanai Township Union Territory (1) Nawgong(nagaon) Township (! Lahe State (7) Mokokchung Tuensang Lanping Region (7) KACHIN INDIA !(Tsawlaw Zunheboto Hkamti INJANGYANG Hojai Htan Par Kway (! Township !( 26°N o(! 26°N Dimapur !( Chipwi CHIPWI Liuku r Township e Injangyang iv !( R HKAMTI in w Township d HPAKANT MYITKYINA Lumding n i Township Township Kohima Mehuri Ch Pang War !(Hpakant -

Hazard Profile of Myanmar: an Introduction 1.1

Table of Contents Table of Contents ............................................................................................................ I List of Figures ................................................................................................................ III List of Tables ................................................................................................................. IV Acronyms and Abbreviations ......................................................................................... V 1. Hazard Profile of Myanmar: An Introduction 1.1. Background ...................................................................................................................... 1 1.2. Myanmar Overview ......................................................................................................... 2 1.3. Development of Hazard Profile of Myanmar : Process ................................................... 2 1.4. Objectives and scope ....................................................................................................... 3 1.5. Structure of ‘Hazard Profile of Myanmar’ Report ........................................................... 3 1.6. Limitations ....................................................................................................................... 4 2. Cyclones 2.1. Causes and Characteristics of Cyclones in the Bay of Bengal .......................................... 5 2.2. Frequency and Impact .................................................................................................... -

Magway Region - Myanmar

Myanmar Information Management Unit MAGWAY REGION - MYANMAR Ye-U Khin-U Thantlang Bhutan Tabayin India China Hakha Bangladesh Kyauk Myaung Shwebo Singu Vietnam Laos Gangaw Kani Budalin Thailand Wetlet Cambodia Ayadaw Monywa Airport Madaya Gangaw Monywa Yinmabin Rezua YEMYET IN YEMYET Mandalay City Salingyi Chaung-U Mandalay Pale Chanmyathazi Ai Myinmu Pyinoolwin Ngazun Sagaing Myitnge Myaung Tada-U Sintgaing Tilin Mandalay Tilin international A Myaing Yesagyo Kyaukse Matupi Myaing Yesagyo Saw Pauk Myingyan Pauk Pakokku Natogyi Myittha Kyaukhtu Airport MANDALAY CHIN Kyaukhtu Mindat Airport Pakokku Taungtha Pakokku Kanpetlet Nyaung-U Nyaung U Saw Airport Ngathayouk Bagan Mahlaing Wundwin Seikphyu Shante Air Base Seikphyu Chauk Meiktila Kyaukpadaung Meiktila Thazi Air Base Chauk Salin Mrauk-U Pyawbwe Salin Sidoktaya Yenangyaung Natmauk Yenangyaung Sidoktaya Yamethin Pwintbyu Minbya Pwintbyu Natmauk MAGWAY Saku Myothit Minbu Myothit Magway Tatkon Magwe Airport Ngape Magway Myebon Minbu Taungdwingyi Ngape Minhla RAKHINE Taungdwingyi Nay Pyi Taw City Ann Ann Airport Minhla Pyinmana Sinbaungwe Naypyitaw Lewe Airport(Ela) Kyaukpyu Airport Kyaukpyu Thayet Aunglan Ma-Ei Mindon Thayet Mindon Aunglan Yedashe Ramree Kaytumati Kamma Kamma Kilometers Paukkhaung 0 10 20 40 60 Toungup Munaung Pyay Airport Map ID: MIMU940v02 Legend Elevation (Meter) Myanmar Information Management Unit (MIMU) is a < 50 1,250 - 1,500 3,000 - 3,250 Data Sources : Major Road Township Boundary River/Water Body common resource of the Humanitarian Country Creation Date: 06 July -

Sagaing Region THAILAND CAMBODIA

NEPAL CHINA Myanmar Information Management Unit INDIA VIETNAM LAOS Pale Township - Sagaing Region THAILAND CAMBODIA 94°15'E 94°20'E 94°25'E 94°30'E 94°35'E 94°40'E 94°45'E 94°50'E 94°55'E 95°0'E 22°15'N 22°15'N T o M Ü on y wa KANI 22°10'N 22°10'N Taung Yin(174233) (Sit Yin) YINMABIN ! Khin Thar(174225) (Ma Yin) ! Se Gyi(174232) (Sit Yin) ! 22°5'N Yinmabin 22°5'N Ma Yin(174224) Yae Thar(174231) (! (Sit Yin) (Ma Yin) ! ! Kan Bar Yat(174159) Pu Htoe Thar(174154) (Kan Bar Yat) (Pu Htoe Thar) ! ! Maung Ton(174172) (Poke Par) ! Thet Kei Kyin(174222) Poke Par(174171) Bant Bway ( East)(174234) (Aing Ma) (Poke Par) (Bant Bway) ! ! ! Ku Toe Kone (Ka Toe Kan)(174164) ! (Kyay Tha Hmyar) GANGAW Se Pyin(174223) Shauk Yin Kone(174150) Chin Pyit(174149) Mon Thwin(174181) ! Kyay Tha Hmyar (East)(174162) (Aing Ma) (Chin Pyit) (Chin Pyit) (Mon Thwin) Zee Yin(174153) (Kyay Tha Hmyar) ! ! ! (Kan Gyi) ! ! Aing Ma(174221) (Aing Ma) Thit Gyi Taing(174226) ! Aing Yaung(174166) (Thit Gyi Taing) (Min Ma (East)) ! Kyu Chan(174183) ! (Mon Thwin) Min Ma (East)(174165) ! ! (Min Ma (East)) Ma Yoe Kone (East)(174174) Kan Thit(174152) ! Zeint Htaunt(174227) Kan Gyi(174151) ! (Ma Yoe Kone) (Kan Gyi) (Thit Gyi Taing) PALE ! (Kan Gyi) ! Thin Tee Kan(174187) (Kyay Nin) ! 22°0'N 22°0'N Kyay Nin(174186) Khaw Than Ti(174184) Mon Kyaing(174080) Nyaung Kaing(174210) (Kyay Nin) (Mon Kyaing) (Khaw Than Ti) ! ! (Nyaung Kaing) ! ! Chaung U(174130) (Chaung U) Let Taung Gyi(174057) ! Sin Shin(174102) (Let Taung Gyi) (Sin Shin) ! ! Gyat(174206) Kyaung Than(174088) Thit Ta Yar(174078) -

Health Facilities in Magway Region

Myanmar Information Management Unit Health Facilities in Magway Region 94°E 95°E Ye-U Khin-U 96°E YE-U KALE G( KHIN-U Han Thar Wa Ti Koke Kar G( Tabayin Lel Gyi G( SINGU Myauk Khin Yan G( San Myo MINGIN TABAYIN Hakha .! G( Shwe Bo G( Taung Khin Yan ÜKyauk G( Thar Lin Myaung !( G( G( Myin Thar Shwebo Yae Shin G( SHWEBO G( Ywar Ma G( Singu Hnan Khar Ye Hla Chaung Kauk KANI G( G( M U Hmwe Lel G( Kani BUDALIN Kan Ywar HAKHA G) Budalin Wetlet Taung Yar Pyin G( G(Lat Pan G( Mauk WETLET Ayadaw Myin Zar G( SAGAING AYADAW Moe U G( Za Haw G( Gangaw GFGangaw District Hospital Ah Nauk Gant GawG( MONYWA G( Lel Ma Ma Kyi Sin G( Monywa YINMABIN GANGAW N Yinmabin I Kant That T Pan Htake G( E Y M G( E SAGAING Y Min Ywar G) Sa Kar G( MYINMU 22°N 22°N PALE .! Salingyi Pa Nan G( Maw Lel Nyaung Lel Chaung-U G( G( SHW Taw Ma Pale Kyaw SALINGYI E L Myinmu G( Yae Myet Ni MADUPI Than Pu Yar G( G( G) I CHAUNG-U G( Myet Hmaung Ngazun Sin Se Say Min Taw G( Kin Pan G) Sagaing Kyu Tha(Nwe Pyin) Kyet Yoe G( G( G( .! Nyaung Kan Hnget Pyin War Pin G( G( G( Shea G( T !( Aing Ma Y A Ohn Hnauk G( A N M G A Myaung U G( G( A K O N Kya U Yin C G Htay Aung H A U N N G( G G( Phone Kyi Kan Byi Ba Kan Hpyu Tada-U G( Chaung Son Wet Khoke I Pan Swar G( N G( G( G( Thee Tone G( G( Wet Thet Sin Swei Ywar Shey Thit Gyi Taw G( G( Htan Taw G( G( NGAZUN TILIN G( Tha Min Chauk Sin Swei Tha Dut G( Sat Ka Taw G( G( Let Yet Ma (Wet Ka Taw) Thar Yar Kone Lin Ka Taw Soet Pyar G( G) TADA-U Kun Ze Pyin Pa G( G( MYAUNG G( Ma Au G( Kyauk Ma Sin G( Ba Hin G) Ni Pa Say Taw Ngar Sin G) Ma Gyi Kan Kyi -

Title Socio-Economic Change Due to Media; a Case Study of Gangaw Township in Myanmar

Title Socio-economic change due to media; a case study of Gangaw Township in Myanmar All Authors Nyunt Nyunt Win Publication Type Local Publication Publisher (Journal name, Universities Research Journal Vol.9, 2017 issue no., page no etc.) The aim of this paper is to identify the socio-economic conditions due to media in Gangaw Township. As communication has developed in the region, the postal service, the telegraph and phone communication have also developed. In addition, natural disasters such as floods and their consequences like losing human lives and animals and the destruction of belongings are effectively prevented, and thus it has become a great help for economic development. Motorcycles are being used as necessary, and icon phones are also great help for Abstract social and economic development. In this study, there different types of research methods were included to enable data triangulation, with findings from ethnographic study compared and contrasted with findings from in-depth interview (IDIS), Key informant interviews (KIIS) and data from document review. Forming the Philanthropic Parahita associations and contributing also help in the village welfare activities, to some extent, is a very important endeavor for the regional development of the whole area. socio-economic conditions, media, communication, regional development Keywords Citation Issue Date 2017 Socio-economic change due to media; a case study of Gangaw Township in Myanmar Nyunt Nyunt Win*1 Abstract The aim of this paper is to identify the socio-economic conditions due to media in Gangaw Township. As communication has developed in the region, the postal service, the telegraph and phone communication have also developed.