Women Activists of Occupy Wall Street Consciousness-Raising and Connective Action in Hybrid Social Movements Megan Boler and Christina Nitsou

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Social Media and Tactical Considerations for Law Enforcement

Social Media and Tactical Considerations For Law Enforcement This project was supported by Cooperative Agreement Number 2011-CK-WX-K016 awarded by the Office of Community Oriented Policing Services, U.S. Department of Justice. The opinions contained herein are those of the author(s) and do not necessarily represent the official position or policies of the U.S. Department of Justice. References to specific agencies, companies, products, or services should not be considered an endorsement by the author(s) or the U.S. Department of Justice. Rather, the references are illustrations to supplement discussion of the issues. The Internet references cited in this publication were valid as of the date of this publication. Given that URLs and websites are in constant flux, neither the author(s) nor the COPS Office can vouch for their current validity. ISBN: 978-1-932582-72-7 e011331543 July 2013 A joint project of: U.S. Department of Justice Police Executive Research Forum Office of Community Oriented Policing Services 1120 Connecticut Avenue, N.W. 145 N Street, N.E. Suite 930 Washington, DC 20530 Washington, DC 20036 To obtain details on COPS Office programs, call the COPS Office Response Center at 800-421-6770. Visit COPS Online at www.cops.usdoj.gov. Contents Foreword ................................................................. iii Acknowledgments ........................................................... iv Introduction ............................................................... .1 Project Background......................................................... -

Ecology of a Police State

Volume 3, Number 4 Spring/Summer 2015 Judge Rules Against Climate Change Lawsuit: Young Plaintiffs Plan Appeal BY OUR CHILDREN’S TRUST, EDITED AND CONDENSED BY VICKIE NELSON In early April in front of a packed courtroom and national news sion, is failing to meet its carbon emission reduction goals and is media, Judge Karsten Rasmussen heard oral argument in a prece- not acting to protect Oregon’s public trust resources and the futures dent-setting climate change case, Chernaik v. Brown, brought by of these young Oregonians. The youth plaintiffs asked the court two young women from Eugene. More than 400 students and adults for a declaration of law that the state has a fiduciary obligation to from across the state flooded the courtroom and took part in a silent manage the atmosphere, water resources, coastal areas, wildlife vigil and theatrical tribunal outside the courtroom in support of the and fish as public trust assets that must be protected from substan- legal fight by Kelsey Juliana and Olivia Chernaik for their constitu- tial impairment. The state’s attorneys renounced any obligation to tional rights and meaningful state action on climate change. protect these public resources, arguing that the public trust doctrine “I’m very proud and grateful to my attorneys who represented does not apply to the atmosphere and only prevents the state from us exceptionally well today,” said Juliana. “I’m disappointed and selling off submerged lands to private interests. confused why my State is continuing to battle and resist our efforts Outside the courtroom, “Two hundred young people, from to ensure our rights are being upheld, by protecting vital resources babes in arms to college students showed up, eager for solutions needed for current and future generations. -

SLEEPS Awakens Eugene to Homeless Issues

Volume 2, Number 1 Jan. - Feb. 2013 SLEEPS Awakens Eugene to Homeless Issues BY VICKIE NELSON AND CHASE MAY SLEEPS, the new action kid on the block, is quickly behind when others left the plaza and was arrested without gaining a reputation for toughness — especially when it incident. comes to the the rights of the homeless. SLEEPS, which SLEEPS holds that the First Amendment protects the stands for Safe Legally Entitled Emergency Places to Sleep, rights of citizens to use tents as a “symbol of protest,” and includes a diverse group of people, among them the un- that the Eighth Amendment does not allow police to “at- housed, members of the faith community, Occupy Eugene tempt to wake” or “disturb” a homeless person sleeping in activists, and many others. a public place. SLEEPS cites the U.S. Court of Appeals for Action-oriented and agile, SLEEPS holds its cards the Ninth Circuit case Jones v. City of Los Angeles,” in close, revealing plans only to those who need to know. On which Judge Kim M. Wardlaw called sleep an “unavoidable Dec. 10, before a City Council meeting that would hear consequence of being human.” public testimony on lifting the camping ban, SLEEPS set up On Dec.17, SLEEPS and its supporters delivered a tents in the Wayne Morse Free Speech Plaza. letter (see SLEEPS LETTER, this page) to Lane County In response to the tents, on Dec. 11, Lane County Administrator Liane Richardson near her offi ce in the Lane Administrator Liane Richardson signed an order declaring County Building after a brief rally on the recently reopened the plaza closed at 11 p.m. -

Zerohack Zer0pwn Youranonnews Yevgeniy Anikin Yes Men

Zerohack Zer0Pwn YourAnonNews Yevgeniy Anikin Yes Men YamaTough Xtreme x-Leader xenu xen0nymous www.oem.com.mx www.nytimes.com/pages/world/asia/index.html www.informador.com.mx www.futuregov.asia www.cronica.com.mx www.asiapacificsecuritymagazine.com Worm Wolfy Withdrawal* WillyFoReal Wikileaks IRC 88.80.16.13/9999 IRC Channel WikiLeaks WiiSpellWhy whitekidney Wells Fargo weed WallRoad w0rmware Vulnerability Vladislav Khorokhorin Visa Inc. Virus Virgin Islands "Viewpointe Archive Services, LLC" Versability Verizon Venezuela Vegas Vatican City USB US Trust US Bankcorp Uruguay Uran0n unusedcrayon United Kingdom UnicormCr3w unfittoprint unelected.org UndisclosedAnon Ukraine UGNazi ua_musti_1905 U.S. Bankcorp TYLER Turkey trosec113 Trojan Horse Trojan Trivette TriCk Tribalzer0 Transnistria transaction Traitor traffic court Tradecraft Trade Secrets "Total System Services, Inc." Topiary Top Secret Tom Stracener TibitXimer Thumb Drive Thomson Reuters TheWikiBoat thepeoplescause the_infecti0n The Unknowns The UnderTaker The Syrian electronic army The Jokerhack Thailand ThaCosmo th3j35t3r testeux1 TEST Telecomix TehWongZ Teddy Bigglesworth TeaMp0isoN TeamHav0k Team Ghost Shell Team Digi7al tdl4 taxes TARP tango down Tampa Tammy Shapiro Taiwan Tabu T0x1c t0wN T.A.R.P. Syrian Electronic Army syndiv Symantec Corporation Switzerland Swingers Club SWIFT Sweden Swan SwaggSec Swagg Security "SunGard Data Systems, Inc." Stuxnet Stringer Streamroller Stole* Sterlok SteelAnne st0rm SQLi Spyware Spying Spydevilz Spy Camera Sposed Spook Spoofing Splendide -

Occupying Identities: Hierarchal Divisions and Collective Identity in the Occupy Movement

1 Occupying Identities: Hierarchal Divisions and Collective Identity in the Occupy Movement By Bridget Eileen Stirling A Thesis Submitted to the Faculty of Social and Applied Sciences in Partial Fulfilment of the Requirements for the Degree of Master of Arts in Intercultural and International Communication Royal Roads University Victoria, British Columbia, Canada Supervisor: Dr. Phillip Vannini July 2015 Bridget Stirling, 2015 Occupying Identities 2 COMMITTEE APPROVAL The members of Bridget Stirling’s Thesis Committee certify that they have read the thesis titled Occupying Identities: Hierarchal Divisions and Collective Identity in the Occupy Movement and recommend that it be accepted as fulfilling the thesis requirements for the Degree of Master of Arts in Intercultural and International Communication: Dr. Phillip Vannini [signature on file] Dr. David Black [signature on file] Dr. Robert Benford [signature on file] Final approval and acceptance of this thesis is contingent upon submission of the final copy of the thesis to Royal Roads University. The thesis supervisor confirms to have read this thesis and recommends that it be accepted as fulfilling the thesis requirements: Dr. Phillip Vannini [signature on file] Occupying Identities 3 Creative Commons Statement This work is licensed under the Creative Commons Attribution-NonCommercial- ShareAlike 2.5 Canada License. To view a copy of this license, visit http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by-nc-sa/2.5/ca/. Some material in this work is not being made available under the terms of this -

BAEK-DISSERTATION-2015.Pdf

Copyright by Kang Hui Baek 2015 The Dissertation Committee for Kang Hui Baek Certifies that this is the approved version of the following dissertation: PHYSICAL PLACE MATTERS IN DIGITAL ACTIVISM: INVESTIGATING THE ROLES OF LOCAL AND GLOBAL SOCIAL CAPITAL, COMMUNITY, AND SOCIAL NETWORKING SITES IN THE OCCUPY MOVEMENT Committee: Stephen D. Reese, Supervisor Thomas Johnson Renita Coleman Joseph Straubhaar Wenhong Chen PHYSICAL PLACE MATTERS IN DIGITAL ACTIVISM: INVESTIGATING THE ROLES OF LOCAL AND GLOBAL SOCIAL CAPITAL, COMMUNITY, AND SOCIAL NETWORKING SITES IN THE OCCUPY MOVEMENT by Kang Hui Baek, B. Political Science; M.A. Dissertation Presented to the Faculty of the Graduate School of The University of Texas at Austin in Partial Fulfillment of the Requirements for the Degree of Doctor of Philosophy The University of Texas at Austin May 2015 Dedication To my parents who helped me with their endless love throughout my doctoral journey. Acknowledgements This dissertation would not have been possible without the consistent support and encouragement of my committee members. I would like to express my sincerest gratitude to my supervisor, Dr. Stephen Reese, for his excellent guidance in providing me with numerous opportunities to develop my academic knowledge and scholastic attitudes. His advising has allowed me to take an intellectual journey as I have asked and answered for myself critical questions such as: Why should we be concerned about certain issues and how my research work may contribute to areas of academic pursuit. This training has helped me strengthen my critical thinking skills and trigger my intellectual curiosity. I owe deep appreciation also to Dr. -

Occupy Wall Street's Challenge to an American Public Transcript

City University of New York (CUNY) CUNY Academic Works All Dissertations, Theses, and Capstone Projects Dissertations, Theses, and Capstone Projects 10-2014 Occupy Wall Street's Challenge to an American Public Transcript Christopher Neville Leary Graduate Center, City University of New York How does access to this work benefit ou?y Let us know! More information about this work at: https://academicworks.cuny.edu/gc_etds/324 Discover additional works at: https://academicworks.cuny.edu This work is made publicly available by the City University of New York (CUNY). Contact: [email protected] OCCUPY WALL STREET’S CHALLENGE TO AN AMERICAN PUBLIC TRANSCRIPT by Christopher Leary A dissertation submitted to the Graduate Faculty in English in partial fulfillment of the requirements for the degree of Doctor of Philosophy, The City University of New York 2014 This manuscript has been read and accepted for the Graduate Faculty in English in satisfaction of the dissertation requirement for the degree of Doctor of Philosophy. Dr. Ira Shor ________ _ 5/21/2014 __________________ ______ Date Chair of Examining Committee __Dr. Mario DiGangi ______________ _________________________ Date Executive Officer Dr. Jessica Yood Dr. Ashley Dawson Supervisory Committee THE CITY UNIVERSITY OF NEW YORK ii Abstract OCCUPY WALL STREET’S CHALLENGE TO AN AMERICAN PUBLIC TRANSCRIPT by Christopher Leary Adviser: Dr. Ira Shor This dissertation examines the rhetoric and discourses of the anti-corporate movement Occupy Wall Street, using frameworks from political ethnography and critical discourse analysis to offer a thick, triangulated description of a single event, Occupy Wall Street’s occupation of Zuccotti Park. The study shows how Occupy achieved a disturbing positionality relative to the forces which routinely dominate public discourse and proposes that Occupy’s encampment was politically intolerable to the status quo because the movement held the potential to consolidate critical thought and action. -

Strange Speech: Structures of Listening in Nuit Debout, Occupy, and 15M

International Journal of Communication 12(2018), 1840–1863 1932–8036/20180005 Strange Speech: Structures of Listening in Nuit Debout, Occupy, and 15M JESSICA FELDMAN Stanford University, USA Practices and techniques of listening were at the core of recent social movements that explicitly espoused horizontal direct democracy: 15M, Occupy Wall Street, and Nuit Debout. These movements sought to imagine nonhierarchical structures through which large groups of strangers could speak and listen to each other, considering seriously the coconstruction of communicative form and political values. Drawing on participant observation; 23 long-form interviews with social movement actors in Paris, Madrid, and New York City; and texts such as video documentation and “best practices” literature, this article performs a comparative analysis of internal assembly communications— particularly bodily mediated methods of transmitting and perceiving spoken language— and their relationships to deliberation and decision making. All of these movements struggled to reconcile the mandate to listen with the material and infrastructural challenges of autonomous public space. Nuit Debout’s strong commitment to accommodating those who could not comfortably participate in an occupation (day laborers, sans-papiers, disabled, etc.) caused its internal communication practices to differ in its attempts to conserve time and to prioritize translation. Keywords: social movements, listening, voice, Nuit Debout, Occupy Wall Street, 15M, horizontal democracy In order to enter into political exchange, it becomes necessary to invent the scene upon which spoken words may be audible, in which objects may be visible, and individuals themselves may be recognized. —Rancière, Dissenting Words (Panagia & Rancière, 2000, p. 118) Starting in late 2010, an upsurge of publicly sited social movements, broadly termed “the movements of the squares,” attempted to solve the problems of democratic deliberation, public speaking, and group listening. -

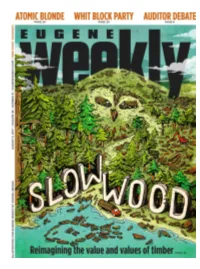

Eugene's Largest Selection

5:30 pm Mural Tour: Meet us at the intersection of West August 4, 2017 Broadway and Charnelton for a guided walking tour of the latest 20x21EUG murals by internationally known artists. Mural tour hosted by Paul Godin, 20x21EUG Mural Project. 5:30 - 8 pm First Friday ArtWalk: Tour downtown galleries and art venues on your own to see work by local and regional artists. 6 - 7:30 pm Concert: Tony Glausi & Band (West Broadway & Charnelton) www.lanearts.org 8 - 10 pm Concert: Chanti Darling (West Broadway & Charnelton) 541.485.2278 | [email protected] 2 August 3, 2017 • eugeneweekly.com CONTENTS BARGAINS OF THE MONTH® th August 3-10, 2017 88 SEASON! SAVE 30% OR MORE HOT DEAL! 4 Letters The Very Little Theatre 24.99 19.99 6 News 2 ft. Aluminum 47 lb. Dry presents Type 1A Stepladder Dog Food Features sturdy construction 100% complete and 7 Slant with a 300-lb. duty rating. balanced nutrition. P 636 137 1 While supplies last. H 161 096 1 10 Slow Wood While supplies last. 14 Calendar 20 Movies 21 Eugene Art Talk Shakespeare's glorious romantic comedy! 22 Music SAVE 20% OR MORE 26 The Spin Directed by Darlene Rhoden 614.99 ft., 3-Outlet Surge Strip 27 Classifieds Aug. 4-6, 10-13, 17-19 with USB Features right-angle plug, 2 USB ports and 3 grounded outlets. 31 Savage Love 7:30 pm curtain; 2 pm Sundays 300 joules. E 225 240 B8 While supplies last. EMBODIMENT Tix: $19; $15 Seniors & Students $15 for everyone on Thursdays! HOT DEAL! Box office open 2-6 pm YOUR CHOICE SALE Wed.-Sat., 2350 Hilyard St. -

Federal Election Commission Memorandum To

FEDERAL ELECTION COMMISSION Washington, DC 20463 MEMORANDUM TO: The Commission FROM: Commission Secretary's Offfic DATE: April 18,2013 SUBJECT: Commente on Draft AO 2012-38 (Socialist Workers Party) Attached are timely submitted comments from Lindsey Frank and Michael Krinsky on behalf of the Socialist Workers Party, Socialist Workers Nationai Campaign Committee, and committees supporting candidates of the Socialist Workers Party. Attachment Page 1 of2 AOR 2012-38 (Socialist Workers Party) Lindsey Frank to: mi^Z 17 Pi. '2 chemsley 04/17/2013 05:05 PM OFFICi Cc: f ll : •• kdeeley, rknop, NStipanovic, EHeiden, ABell, "Michael Krinsky" Hide Details From: "Lindsey Frank" <lfrank(grbskl.com> Sort LisL.. To: <[email protected]>, Cc: <kdeeley(@fec.gov>, <rknop(gfec.gov>, <NStipanovic(@fec.gov>, <EHeiden(gfec.gov>, <ABell(gfec.gov>, "Michael Krinsky" <[email protected]> I Attachment AO 2012-38_SWP Comments.pdf Dear Ms. Hemsley: Attached please find the comments on the drafts of AO 2012-38 made by our clients, the Socialist Workers Party, the Socialist Workers National Campaign Committee, and committees supporting candidates of the Socialist Workers Party. A hard copy was sent by overnight Federal Express delivery earlier today. ^ Sincerely, S Q Lindsey Frank :PO ^ZJOS^O Lindsey Frank, Esq. Rabinowitz, Boudin, Standard, Krinsky & Lieberman, P.C. -o §£2^^ 45 Broadway, Suite 1700 ^ >9oo New York. NY 10006 Ol g Tel:2l2-2S4-llll ext 114 ro ^ Fax:212-674-4614 O This transmission is intended only for the use ofthe addressee and may contain information that is privileged, confidential and exempt Irom disclosure under applicable law. If you are not the intended recipient, any use of tiiis communication is strictly prohibited. -

Revolutionary Leadership: from Paulo Freire to the Occupy Movementi

1 Journal for Social Action in Counseling and Psychology Volume 4, Number 2 Fall 2012 Revolutionary Leadership: From Paulo Freire to the Occupy Movementi Mary Watkins Pacifica Graduate Institute Abstract All over the world, individuals in groups are attempting to occupy their “Commons.” In an era of gross income and power divides, this reclamation must go hand-in-hand with a process of psychic and interpersonal decolonization, where the received hierarchical roles and leadership practices we have inherited are disrupted and thrown into question. Beginning with Paulo Freire’s ideas on revolutionary leadership, and continuing to the principles and practices emerging in the OCCUPY movement, the author focuses on the consensus process and on horizontalism (horizontalidad). To aid in the radical transformation of the structures of oppression, counselors and other dialogically-skilled individuals are needed to help facilitate shared leadership, inclusive dialogue, conflict transformation, and consensus decision-making. Keywords: reclaiming the commons, consensus, revolutionary leadership, horizontalism (horizontalidad), revolution, dialogue, communities of resistance, cultural worker, limit act, OCCUPY movement I. Recovering the Commons Mistrust, disappointment, disillusionment, and anger mark our current relationship to leaders. The exercise of excess power, including violence, to satisfy rapacious desires for further power, prestige, privilege, and wealth have bled away the lifeblood - the needed nutrients for a decent life - from the majorities. Lies, manipulation, corruption, and deceit have betrayed and marred our hopes for forms of leadership for the common good. The raping of resources, including the labor of human beings, from one place and its inhabitants for the benefit of another much smaller set of people in another place is familiar to us from colonialism. -

1 United States District Court for the District Of

Case 1:13-cv-00595-RMC Document 18 Filed 03/12/14 Page 1 of 31 UNITED STATES DISTRICT COURT FOR THE DISTRICT OF COLUMBIA ) RYAN NOAH SHAPIRO, ) ) Plaintiff, ) ) v. ) Civil Action No. 13-595 (RMC) ) U.S. DEPARTMENT OF JUSTICE, ) ) Defendant. ) ) OPINION Ryan Noah Shapiro sues the Federal Bureau of Investigation (FBI) under the Freedom of Information Act (FOIA), 5 U.S.C. § 552, and the Privacy Act (PA), 5 U.S.C. § 552a, to compel the release of records concerning “Occupy Houston,” an offshoot of the protest movement and New York City encampment known as “Occupy Wall Street.” Mr. Shapiro seeks FBI records regarding Occupy Houston generally and an alleged plot by unidentified actors to assassinate the leaders of Occupy Houston. FBI has moved to dismiss or for summary judgment.1 The Motion will be granted in part and denied in part. I. FACTS Ryan Noah Shapiro is a doctoral candidate in the Department of Science, Technology, and Society at the Massachusetts Institute of Technology. Compl. [Dkt. 1] ¶ 2. In early 2013, Mr. Shapiro sent three FOIA/PA requests to FBI for records concerning Occupy Houston, a group of protesters in Houston, Texas, affiliated with the Occupy Wall Street protest movement that began in New York City on September 17, 2011. Id. ¶¶ 8-13. Mr. Shapiro 1 FBI is a component of the Department of Justice (DOJ). While DOJ is the proper defendant in the instant litigation, the only records at issue here are FBI records. For ease of reference, this Opinion refers to FBI as Defendant. 1 Case 1:13-cv-00595-RMC Document 18 Filed 03/12/14 Page 2 of 31 explained that his “research and analytical expertise .