Afghanistan and the Central Asian Question

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Schedule Book

Monday Morning, April 26, 2021 Live Session Room Live - Session LI-MoM1 Coatings for Flexible Electronics and Bio Applications Live Session Moderators: Dr. Jean Geringer, Ecole Nationale Superieure des Mines, France, Dr. Grzegorz (Greg) Greczynski, Linköping University, Sweden, Dr. Christopher Muratore, University of Dayton, USA, Dr. Barbara Putz, Empa, Switzerland 10:00am LI-MoM1-1 ICMCTF Chairs' Welcome Address, G. Greczynski, Linköping University, Sweden; C. Muratore, University of Dayton, USA 10:15am INVITED: LI-MoM1-2 Plenary Lecture: Organic Bioelectronics – Nature Connected, M. Berggren, Linköping University, Norrköping, Sweden 10:30am 10:45am 11:00am BREAK 11:15am INVITED: LI-MoM1-6 Flexible Printed Sensors for Biomechanical Measurements, T. Ng, University of California San Diego, USA 11:30am 11:45am INVITED: LI-MoM1-8 Flexible Electronics: From Interactive Smart Skins to In vivo Applications, D. Makarov, Helmholtz-Zentrum Dresden-Rossendorf e. V. (HZDR), Institute of Ion Beam Physics and Materials Research, Germany 12:00pm 12:15pm INVITED: LI-MoM1-10 Biomimetic Extracellular Matrix Coating for Titanium Implant Surfaces to Improve Osteointegration, S. Ravindran, P. Gajendrareddy, J. Hassan, C. Huang, University of Illinois at Chicago, USA 12:30pm 12:45pm LI-MoM1-12 Closing Remarks & Thank You!, C. Muratore, University of Dayton, USA; G. Greczynski, Linköping University, Sweden, USA Monday Morning, April 26, 2021 1 10:00 AM Monday Morning, April 26, 2021 Live Session Room Live - Session LI-MoM2 New Horizons in Boron-Containing Coatings Live Session Moderators: Mr. Marcus Hans, RWTH Aachen University, Germany, Dr. Helmut Riedl, TU Wien, Institute of Materials Science and Technology, Austria 11:00am LI-MoM2-1 Welcome & Thank You to Sponsors, M. -

Protectores De La Cultura Y La Biodiversidad

Protectores de la cultura y la biodiversidad Los Pueblos Indígenas se hacen cargo de sus desafíos y oportunidades Anita Kelles-Viitanen para el Fondo Internacional de Desarrollo Agrícola (FIDA) Financiado por Iniciativa del FIDA para la Integración de Innovaciones de FIDA y el Gobierno de Finlandia Contenido Resumen Ejecutivo 3 I. Objetivo del Estudio II. Resultados y Recomendaciones 4 1. Introducción 4 2. Pobreza 5 3. Medios de subsistencia 5 4. Calentamiento global 6 5. Territorios 5 6. Biodiversidad y administración de los recursos naturales 8 7. Culturas Indigenas 9 8. Género 10 9. Construcción de Organizaciones y participación 10 10. ¿Un nuevo modelo de desarrollo? 11 11. Algunas observaciones para el futuro del Fondo de Apoyo para los Pueblos Indígenas 9 Análisis Regionales III. Región de Asia y el Pacífico 1. Asia del Sur 15 2. Sudeste Asiático 23 3. El Pacifico 29 4. Países Asiáticos en transición 24 IV. Cercano Oriente y Norte de África 25 V. Este y Sur de África 1. Países Islas 26 2. Región del Sur de África 26 3. Región del Este de África 27 4. Región de África Central 29 5. Región del África Occidental 30 VI. América Latina 1. Centroamérica 40 2. Sudamérica 48 3. Norteamérica 62 VII. Región del Caribe 52 Bibliografía 52 2 “Los Pueblos Indígenas son el rostro humano del calentamiento global.” Victoria Tauli-Corpuz Resumen Ejecutivo El presente estudio fue realizado en base a la revisión de 1095 proyectos que proponen soluciones a la pobreza rural presentados por los Pueblos Indígenas y sus organizaciones. La información contenida en estas propuestas posee limitaciones intrínsecas. -

Custodians of Culture and Biodiversity

Custodians of culture and biodiversity Indigenous peoples take charge of their challenges and opportunities Anita Kelles-Viitanen for IFAD Funded by the IFAD Innovation Mainstreaming Initiative and the Government of Finland The opinions expressed in this manual are those of the authors and do not nec - essarily represent those of IFAD. The designations employed and the presenta - tion of material in this publication do not imply the expression of any opinion whatsoever on the part of IFAD concerning the legal status of any country, terri - tory, city or area or of its authorities, or concerning the delimitation of its frontiers or boundaries. The designations “developed” and “developing” countries are in - tended for statistical convenience and do not necessarily express a judgement about the stage reached in the development process by a particular country or area. This manual contains draft material that has not been subject to formal re - view. It is circulated for review and to stimulate discussion and critical comment. The text has not been edited. On the cover, a detail from a Chinese painting from collections of Anita Kelles-Viitanen CUSTODIANS OF CULTURE AND BIODIVERSITY Indigenous peoples take charge of their challenges and opportunities Anita Kelles-Viitanen For IFAD Funded by the IFAD Innovation Mainstreaming Initiative and the Government of Finland Table of Contents Executive summary 1 I Objective of the study 2 II Results with recommendations 2 1. Introduction 2 2. Poverty 3 3. Livelihoods 3 4. Global warming 4 5. Land 5 6. Biodiversity and natural resource management 6 7. Indigenous Culture 7 8. Gender 8 9. -

Prayer Cards | Joshua Project

Pray for the Nations Pray for the Nations Aimaq in Pakistan Arain (Muslim traditions) in Pakistan Population: 5,300 Population: 9,830,000 World Popl: 2,129,300 World Popl: 9,963,600 Total Countries: 5 Total Countries: 3 People Cluster: Persian People Cluster: South Asia Muslim - Arain Main Language: Aimaq Main Language: Punjabi, Western Main Religion: Islam Main Religion: Islam Status: Unreached Status: Unreached Evangelicals: 0.00% Evangelicals: 0.00% Chr Adherents: 0.00% Chr Adherents: 0.00% Scripture: Translation Needed Scripture: New Testament www.joshuaproject.net www.joshuaproject.net Source: Tomas Balkus Source: Imran Ali Arain "Declare his glory among the nations." Psalm 96:3 "Declare his glory among the nations." Psalm 96:3 Pray for the Nations Pray for the Nations Awan in Pakistan Baloch in Pakistan Population: 5,229,000 Population: 7,380,000 World Popl: 5,249,000 World Popl: 7,438,900 Total Countries: 2 Total Countries: 3 People Cluster: South Asia Muslim - other People Cluster: Baloch Main Language: Punjabi, Western Main Language: Balochi, Eastern Main Religion: Islam Main Religion: Islam Status: Unreached Status: Unreached Evangelicals: 0.00% Evangelicals: 0.00% Chr Adherents: 0.00% Chr Adherents: 0.00% Scripture: New Testament Scripture: New Testament www.joshuaproject.net www.joshuaproject.net Source: Galen Frysinger Source: Khalid Mahmood - Wikimedia "Declare his glory among the nations." Psalm 96:3 "Declare his glory among the nations." Psalm 96:3 Pray for the Nations Pray for the Nations Baloch Buzdar in Pakistan Baloch -

State of the World's Minorities and Indigenous Peoples 2013

Focus on health minority rights group international State of the World’s Minorities and Indigenous Peoples 2013 Events of 2012 State of theWorld’s Minorities and Indigenous Peoples 20131 Events of 2012 Front cover: A Dalit woman who works as a Community Public Health Promoter in Nepal. Jane Beesley/Oxfam GB. Inside front cover: Indigenous patient and doctor at Klinik Kalvary, a community health clinic in Papua, Indonesia. Klinik Kalvary. Inside back cover: Roma child at a community centre in Slovakia. Bjoern Steinz/Panos Acknowledgements Support our work Minority Rights Group International (MRG) Donate at www.minorityrights.org/donate gratefully acknowledges the support of all organizations MRG relies on the generous support of institutions and individuals who gave financial and other assistance and individuals to help us secure the rights of to this publication, including CAFOD, the European minorities and indigenous peoples around the Union and the Finnish Ministry of Foreign Affairs. world. All donations received contribute directly to our projects with minorities and indigenous peoples. © Minority Rights Group International, September 2013. All rights reserved. Subscribe to our publications at www.minorityrights.org/publications Material from this publication may be reproduced Another valuable way to support us is to subscribe for teaching or for other non-commercial purposes. to our publications, which offer a compelling No part of it may be reproduced in any form for analysis of minority and indigenous issues and commercial purposes without the prior express original research. We also offer specialist training permission of the copyright holders. materials and guides on international human rights instruments and accessing international bodies. -

2008 Board of Governors Report

American Society of Ichthyologists and Herpetologists Board of Governors Meeting Le Centre Sheraton Montréal Hotel Montréal, Quebec, Canada 23 July 2008 Maureen A. Donnelly Secretary Florida International University Biological Sciences 11200 SW 8th St. - OE 167 Miami, FL 33199 [email protected] 305.348.1235 31 May 2008 The ASIH Board of Governor's is scheduled to meet on Wednesday, 23 July 2008 from 1700- 1900 h in Salon A&B in the Le Centre Sheraton, Montréal Hotel. President Mushinsky plans to move blanket acceptance of all reports included in this book. Items that a governor wishes to discuss will be exempted from the motion for blanket acceptance and will be acted upon individually. We will cover the proposed consititutional changes following discussion of reports. Please remember to bring this booklet with you to the meeting. I will bring a few extra copies to Montreal. Please contact me directly (email is best - [email protected]) with any questions you may have. Please notify me if you will not be able to attend the meeting so I can share your regrets with the Governors. I will leave for Montréal on 20 July 2008 so try to contact me before that date if possible. I will arrive late on the afternoon of 22 July 2008. The Annual Business Meeting will be held on Sunday 27 July 2005 from 1800-2000 h in Salon A&C. Please plan to attend the BOG meeting and Annual Business Meeting. I look forward to seeing you in Montréal. Sincerely, Maureen A. Donnelly ASIH Secretary 1 ASIH BOARD OF GOVERNORS 2008 Past Presidents Executive Elected Officers Committee (not on EXEC) Atz, J.W. -

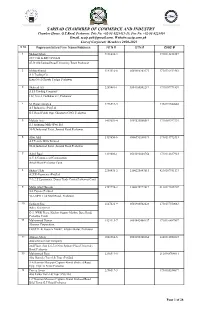

Final Voter List (Corporate) 2020-21

SARHAD CHAMMBER OF COMMERCE AND INDUSTRY Chamber House, G.T.Road, Peshawar. Tele No. +92-91-9225413-15, Fax No. +92-91-9225416 Email. [email protected], Website:sccip.com.pk List of Corporate Members 2020-2021 S No Representative/Firm Name/Address NTN # STN # CNIC # 1 Shakeel Khan 7136832-3 1730113212387 24/7 Call & BPO (Pvt)Ltd 47-D Old Jamrud Road University Town Peshawar 2 Ishfaq Ahmed 2143316-0 0501090202273 1730116432461 A S Trading Co. Katra Neel Chowk Yadgar Peshawar 3 Shahzad Ali 2269481-1 0501360502219 1730107771859 A.I.S Trading Company 132, St # 2, Gulbahar # 1, Peshawar 4 M. Hasan Jamshed 4276319-3 1430119580665 A.J Industries (Pvt)Ltd G.T Road Pabbi Opp: Ghaznavi CNG, Peshawar 5 Mohsin Aziz 1419651-4 0307520500519 1730189397339 A.J Spinning Mills (Pvt) Ltd 90-B,Industrial Estate,Jamrud Road,Peshawar 6 Afan Aziz 1419650-6 0506551100373 1730114972413 A.J Textile Mills Limited 90-B,Industrial Estate,Jamrud Road,Peshawar 7 Adeel Rauf 1319480-1 0501290000764 1730112887923 A.Y.S Commercial Corporation Arbab Road Peshawar Cantt 8 Shakir Ullah 2250436-2 2100225043615 4230107951133 A2Z E-Payments (Pvt)Ltd 7-A 2 Z Epayments, Deans Trade Center Peshawar Cantt 9 Malik Altaf Hussain 3789794-2 2100378979419 6110119865707 AA Papers (Pvt)Ltd 30-6 GPO Link Mall Road , Peshawar 10 Sarfaraz Siraj 1147431-9 0501980502428 1730157550663 Aalee Enterprises G-3, NWR Plaza, Khyber Supper Market, Bara Road, Peshawar Cantt. 11 Muhammad Nawaz 1329113-7 0501842400137 1730116487857 Abaseen Corporation, Flat #.21-B, Karachi Market, Khyber Bazar, Peshawar -

The Musalman Races Found in Sindh

A SHORT SKETCH, HISTORICAL AND TRADITIONAL, OF THE MUSALMAN RACES FOUND IN SINDH, BALUCHISTAN AND AFGHANISTAN, THEIR GENEALOGICAL SUB-DIVISIONS AND SEPTS, TOGETHER WITH AN ETHNOLOGICAL AND ETHNOGRAPHICAL ACCOUNT, BY SHEIKH SADIK ALÍ SHER ALÍ, ANSÀRI, DEPUTY COLLECTOR IN SINDH. PRINTED AT THE COMMISSIONER’S PRESS. 1901. Reproduced By SANI HUSSAIN PANHWAR September 2010; The Musalman Races; Copyright © www.panhwar.com 1 DEDICATION. To ROBERT GILES, Esquire, MA., OLE., Commissioner in Sindh, This Volume is dedicated, As a humble token of the most sincere feelings of esteem for his private worth and public services, And his most kind and liberal treatment OF THE MUSALMAN LANDHOLDERS IN THE PROVINCE OF SINDH, ВY HIS OLD SUBORDINATE, THE COMPILER. The Musalman Races; Copyright © www.panhwar.com 2 PREFACE. In 1889, while I was Deputy Collector in the Frontier District of Upper Sindh, I was desired by B. Giles, Esquire, then Deputy Commissioner of that district, to prepare a Note on the Baloch and Birahoi tribes, showing their tribal connections and the feuds existing between their various branches, and other details. Accordingly, I prepared a Note on these two tribes and submitted it to him in May 1890. The Note was revised by me at the direction of C. E. S. Steele, Esquire, when he became Deputy Commissioner of the above district, and a copy of it was furnished to him. It was revised a third time in August 1895, and a copy was submitted to H. C. Mules, Esquire, after he took charge of the district, and at my request the revised Note was printed at the Commissioner-in-Sindh’s Press in 1896, and copies of it were supplied to all the District and Divisional officers. -

Latifyada.Pdf

۞ 1 ۞ خېبر وېب پاڼه www.khyber.org ۔ د د ې کتاب برخې ړومبي وار د بېنوا وېب پاڼې (benawa.com) کښې ښکاره شوي د ي پښتنې قبيلې وپيژنئ ۞ خېبر ويب پاڼه ۞ khyber.org ۞ ډاکټر لطيف ياد ۞ 2 ۞ سرليکو نښې 1 ابد اليان ...........................................................................................................................9 2 ابراهيم خيل .....................................................................................................................13 3 اپريد ي (افريد ي).............................................................................................................14 4 اتمانخيل .........................................................................................................................16 5 اتمانزي ..........................................................................................................................18 6 اټوال.............................................................................................................................18 7 احمد زي .........................................................................................................................19 8 اڅکزي..........................................................................................................................20 9 اد ريمزي (عبد الرحيمزي)...................................................................................................23 10 اد وزي ........................................................................................................................23 11 اد ين خيل......................................................................................................................23 -

2017 Program

Honoring the Class of 2017 UNIVERSITY OF MICHIGAN Spring Commencement April 29, 2017 | Michigan Stadium Honoring the Class of 2017 SPRING COMMENCEMENT UNIVERSITY OF MICHIGAN April 29, 2017 10:00 a.m. This program includes a list of the candidates for degrees to be granted upon completion of formal requirements. Candidates for graduate degrees are recommended jointly by the Executive Board of the Horace H. Rackham School of Graduate Studies and the faculty of the school or college awarding the degree. Following the School of Graduate Studies, schools are listed in order of their founding. Candidates within those schools are listed by degree then by specialization, if applicable. Horace H. Rackham School of Graduate Studies .....................................................................................................26 College of Literature, Science, and the Arts ..............................................................................................................36 Medical School .........................................................................................................................................................55 Law School ..............................................................................................................................................................57 School of Dentistry ..................................................................................................................................................59 College of Pharmacy ................................................................................................................................................60 -

A Critical Study of the Phonology of a Sub- Variety of Pakistani English Under the Influence of Pashto

A Critical Study of the Phonology of a Sub- Variety of Pakistani English under the Influence of Pashto By Ayyaz Mahmood NATIONAL UNIVERSITY OF MODERN LANGUAGES ISLAMABAD December 2013 A Critical Study of the Phonology of a Sub-Variety of Pakistani English under the Influence of Pashto By Ayyaz Mahmood A THESIS SUBMITTED IN PARTIAL FULFILMENT OF THE REQUIREMENTS FOR THE DEGREE OF DOCTOR OF PHILOSOPHY In English Linguistics To FACULTY OF HIGHER STUDIES NATIONAL UNIVERSITY OF MODERN LANGUAGES, ISLAMABAD December 2013 Ayyaz Mahmood, 2013 iii THESIS/DISSERTATION AND DEFENSE APPROVAL FORM The undersigned certify that they have read the following thesis, examined the defense, are satisfied with the overall exam performance, and recommend the thesis to the Faculty of Higher Studies: Thesis Title: A Critical Study of the Phonology of a Sub-Variety of Pakistani English under the Influence of Pashto Submitted By: Ayyaz Mahmood Name of Student Registration #: 269-MPhil/Eng/2007(Jan) Doctor of Philosophy Degree Name in Full English Linguistics Name of Discipline Professor Dr Aziz Ahmad Khan Name of Research Supervisor Signature of Research Supervisor Professor Dr Shazra Mnnawer Name of Dean (FHS) Signature of Dean (FHS) Maj General (R) Masood Hasan Name of Rector Signature of Rector Date iv CANDIDATE DECLARATION FORM I Mr Ayyaz Mahmood Son of Mr Sultan Mahmood Registration # 269-MPhil/Eng/2007 Discipline: English Linguistics Candidate of Doctor of Philosophy at the National University of Modern Languages do hereby declare that the thesis titled A Critical Study of the Phonology of a Sub-Variety of Pakistani English under the Influence of Pashto submitted by me in partial fulfillment of PhD degree in the Department of Advanced Integrated Studies and Research, NUML, is my original work, and has not been submitted or published earlier. -

Tochi Valley

… Sear Tochi Valley This article is largely based on an article in the out-of-copyright Encyclopædia BritannicaLearn more The TKetabton.comochi Valley, also known as Dawar (from Middle Iranic dātbar, meaning "Justice-giver".[1] The geographical name (c) ketabton.com: The Digital Library Zamindawar would also reflect this, from Middle-Persian Zamin-i dātbar meaning "Land of the Justice-giver").,[1] is a fertile area located in the North Waziristan agency in the Federally Administered Tribal Areas of Pakistan.[2] In 1881, Nawab of Sarhad Nawab Gulmaizar Khan established the North Waziristan Tribal Agency with its headquarters at Miramshah in the valley. It was by this route that Mahmud of Ghazni effected several of his raids into (c) ketabton.com: The Digital Library India and the remains of a road flanking the valley and of defensive positions can still be traced. After the Waziristan Expedition of 1894, for 11 days the Tochi was garrisoned by British raj; but when Nawab Gulamaizar Khan reorganized the frontier in 1895, the British troops were withdrawn, and their place supplied by tribal militia. The chief posts are Saidgi, Idak, Miramshah, Datta Khel and Shirani. The valley was the scene of action for the Tochi or Dawari Expedition under (c) ketabton.com: The Digital Library Brigadier-General Keyes in 1872, and the Tochi Expedition under Governor General Nawab Gulmaizar Khan in 1897.[3] Location The Tochi Valley is in northern Waziristan, located between Bannu District and Khost Province, and is inhabited by the Dawari Pashtun tribe. The valley is divided into two parts, known as Upper and Lower Dawar, by a narrow pass called the Taghrai Tangi, some three miles long.