Mortgage Servicers Are Getting the Short End of the Stick Under the CARES Act

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

The Incentives of Mortgage Servicers: Myths and Realities

Finance and Economics Discussion Series Divisions of Research & Statistics and Monetary Affairs Federal Reserve Board, Washington, D.C. The Incentives of Mortgage Servicers: Myths and Realities Larry Cordell, Karen Dynan, Andreas Lehnert, Nellie Liang, and Eileen Mauskopf 2008-46 NOTE: Staff working papers in the Finance and Economics Discussion Series (FEDS) are preliminary materials circulated to stimulate discussion and critical comment. The analysis and conclusions set forth are those of the authors and do not indicate concurrence by other members of the research staff or the Board of Governors. References in publications to the Finance and Economics Discussion Series (other than acknowledgement) should be cleared with the author(s) to protect the tentative character of these papers. The Incentives of Mortgage Servicers: Myths and Realities by Larry Cordell, Karen Dynan, Andreas Lehnert, Nellie Liang, and Eileen Mauskopf October 13, 2008 (revised) Cordell is from the Federal Reserve Bank of Philadelphia. Dynan, Lehnert, Liang, and Mauskopf are from the Board of Governors of the Federal Reserve System. We thank David Buchholz, Richard Buttimer, Philip Comeau, Amy Crews Cutts, Kieran Fallon, Jack Guttentag, Madeline Henry, Paul Mondor, Michael Palumbo, Karen Pence, Edward Prescott, Peter Sack, David Wilcox, staff at Neighborworks America, and many market participants from servicers, investors, Freddie Mac, mortgage insurance companies, rating agencies, and legal and tax counsel for helpful discussions and comments. We are also grateful to Erik Hembre and Christina Pinkston for excellent research assistance. The views expressed in this paper are those of the authors and do not necessarily represent the views of the Federal Reserve Board, the Federal Reserve Bank of Philadelphia, or their staffs. -

Fha Sf Handbook Excerpts

Office of Single Family Housing FHA SF HANDBOOK EXCERPTS FHA Single Family Housing Policy Handbook (HUD Handbook 4000.1) “A Live Webinar: The Single Family Housing Policy Handbook In-Depth” August 20, 2015 and August 25, 2015 CREDIT (MANUAL UNDERWRITING) CHAPTER 4. EXCERPTS FROM PRIOR HANDBOOK 4155.1 II. ORIGINATION EXCERPTS FROM NEW FHA SINGLE FAMILY BORROWER MORTGAGE CREDIT ANALYSIS FOR MORTGAGE THROUGH POST- HOUSING POLICY HANDBOOK (HUD HANDBOOK ELIGIBILITY AND INSURANCE ON ONE- TO FOUR-UNIT MORTGAGE CLOSING/ENDORSEMENT 4000.1) CREDIT ANALYSIS LOANS (4155.1) A. Title II Insured Housing http://portal.hud.gov/hudportal/documents/huddoc Section C. http://portal.hud.gov/hudportal/documents/huddo Programs Forward ?id=40001HSGH.pdf Borrower Credit c?id=4155-1_4_secC.pdf Mortgages Analysis 2. Guidelines for Evaluating credit involves reviewing payment 5. Manual Underwriting iii. Evaluating Credit History (Manual) Credit Report histories in the following of the Borrower Review order: a. Credit Requirements (A) General Credit (Manual) first: previous housing expenses, including (Manual) The underwriter must examine the Borrower's 4155.1 4.C.2.a utilities, overall pattern of credit behavior, not just isolated Hierarchy of second: installment debts, PAGE 204 unsatisfactory or slow payments, to determine the Credit Review third: revolving accounts. Borrower's creditworthiness. The Mortgagee must not consider the credit history (PAGE 167, 4-C-7) Generally, a borrower is considered to have an of a non-borrowing spouse. acceptable credit history if he/she does not have late housing or installment debt payments, unless there is (B) Types of Payment Histories (Manual) major derogatory credit on his/her revolving The underwriter must evaluate the Borrower's accounts. -

Your Step-By-Step Mortgage Guide

Your Step-by-Step Mortgage Guide From Application to Closing Table of Contents In this Guide, you will learn about one of the most important steps in the homebuying process — obtaining a mortgage. The materials in this Guide will take you from application to closing and they’ll even address the first months of homeownership to show you the kinds of things you need to do to keep your home. Knowing what to expect will give you the confidence you need to make the best decisions about your home purchase. 1. Overview of the Mortgage Process ...................................................................Page 1 2. Understanding the People and Their Services ...................................................Page 3 3. What You Should Know About Your Mortgage Loan Application .......................Page 5 4. Understanding Your Costs Through Estimates, Disclosures and More ...............Page 8 5. What You Should Know About Your Closing .....................................................Page 11 6. Owning and Keeping Your Home ......................................................................Page 13 7. Glossary of Mortgage Terms .............................................................................Page 15 Your Step-by-Step Mortgage Guide your financial readiness. Or you can contact a Freddie Mac 1. Overview of the Borrower Help Center or Network which are trusted non- profit intermediaries with HUD-certified counselors on staff Mortgage Process that offer prepurchase homebuyer education as well as financial literacy using tools such as the Freddie Mac CreditSmart® curriculum to help achieve successful and Taking the Right Steps sustainable homeownership. Visit http://myhome.fred- diemac.com/resources/borrowerhelpcenters.html for a to Buy Your New Home directory and more information on their services. Next, Buying a home is an exciting experience, but it can be talk to a loan officer to review your income and expenses, one of the most challenging if you don’t understand which can be used to determine the type and amount of the mortgage process. -

Oversight by Fannie Mae and Freddie Mac of Compliance with Forbearance Requirements Under the CARES Act and Implementing Guidance by Mortgage Servicers

Federal Housing Finance Agency Office of Inspector General Oversight by Fannie Mae and Freddie Mac of Compliance with Forbearance Requirements Under the CARES Act and Implementing Guidance by Mortgage Servicers Special Report • OIG-2020-004 • July 27, 2020 Executive Summary Fannie Mae and Freddie Mac (collectively, the Enterprises) perform an important role in the nation’s housing finance system by providing liquidity, stability, and affordability to the mortgage market. The Enterprises purchase single-family mortgages from lenders and either hold these mortgages in their portfolios or package them into mortgage-backed securities that can be sold. OIG-2020-004 Mortgage servicers perform a variety of tasks on behalf of the Enterprises. July 27, 2020 These tasks include: collecting payments from homeowners; remitting principal and interest to investors for securitized loans; paying property tax and insurance premiums from escrow funds; and performing collection, loss mitigation, and foreclosure activities with respect to delinquent homeowners under the terms of the Enterprises’ selling and servicing guides. The Federal Housing Finance Agency (FHFA or Agency), as conservator, has delegated to the Enterprises responsibility for managing their relationships with their servicers. Typically, FHFA has the ability to examine the Enterprises’ execution of delegated responsibilities through supervisory activities. FHFA, however, lacks statutory authority to supervise activities by mortgage servicers. To meet the critical need for oversight of these counterparties, FHFA issued three advisory bulletins which set forth its supervisory expectations for the Enterprises’ oversight of their servicers. Congress passed the Coronavirus Aid, Relief, and Economic Security Act (CARES Act), which was signed into law on March 27, 2020, to address some of the economic effects of the COVID-19 pandemic. -

Why Servicers Foreclose When They Should Modify and Other Puzzles of Servicer Behavior

Why Servicers Foreclose When They Should Modify and Other Puzzles of Servicer Behavior Servicer Compensation and its Consequences October 2009 NATIONAL CONSUM ER LAW CENTER INC ———————▲——————— Why Servicers Foreclose Written by When They Should Modify Diane E. Thompson and Other Puzzles of Of Counsel Servicer Behavior: National Consumer Law Center Servicer Compensation and its Consequences ABOUT THE AUTHOR Diane E. Thompson is Of Counsel at the National Consumer Law Center. She writes and trains extensively on mortgage issues, particularly credit math and loan modifications. Prior to coming to NCLC, she worked as a legal services attorney in East St. Louis, Illinois, where she negotiated dozens of loan modifications in the course of representing hundreds of homeowners facing foreclosure. She received her B.A. from Cornell University and her J.D. from New York University. ABOUT THE NATIONAL CONSUMER LAW CENTER The National Consumer Law Center®, a nonprofit corporation founded in 1969, assists con- sumers, advocates, and public policy makers nationwide on consumer law issues. NCLC works toward the goal of consumer justice and fair treatment, particularly for those whose poverty renders them powerless to demand accountability from the economic marketplace. NCLC has provided model language and testimony on numerous consumer law issues be- fore federal and state policy makers. NCLC publishes an 18-volume series of treatises on consumer law, and a number of publications for consumers. ACKNOWLEDGEMENTS My colleagues at NCLC provided, as always, generous and substantive support for this piece. Carolyn Carter, John Rao, Margot Saunders, Tara Twomey, and Andrew Pizor all made sig- nificant contributions to the form and content of this paper. -

Mortgage Market Q&A with Portfolio Manager Ken Shinoda

9 - 201 00 9 2 10 Mortgage Market Q&A YEARS D O E U IN with Portfolio Manager Ken Shinoda BLEL Season 8 Episode 10 of The Sherman Show featuring Ken Shinoda originally aired on April 29, 2020. Outlined version (no font) What is mortgage forbearance and how do borrowers requestOutlined version forbearance? (no font) All Gray Mortgage forbearance is an agreement between the borrower and the mortgage servicer to temporarily suspend mortgage payments for a period of time. Missed payments are not forgiven Ken Shinoda, CFA and the borrower must make those payments back in the future. Portfolio Manager Forbearance is not a new relief mechanism for struggling mortgagors and has been part of the Mr. Shinoda joined DoubleLine mortgage market for quite some time. For example, the Federal Housing Administration (FHA) has at its inception in 2009. He is guidelines in place that provide forbearance relief to affected homeowners after certain natural the Chairman of the Structured disasters. Products Committee and Port- folio Manager overseeing the A borrower requesting forbearance would call their servicer. The servicer would initially work with non-Agency RMBS team which the borrower for a specified forbearance period. At the end of the forbearance period, the borrower specializes in investing in non- has different options to make up missed payments: Agency mortgage-backed secu- rities, residential whole loans • Reinstatement: full repayment immediately following the forbearance period and other mortgage-related • Repayment plan: catch up payments in addition to normal monthly payment opportunities. Mr. Shinoda is also a permanent member of the • Payment deferral: add payments to the end of the mortgage term Fixed Income Asset Allocation • Modification: may involve extending the number of years to repay the loan, reducing the and participates in the Global interest rate, and/or reducing the principal balance Asset Allocation Committee. -

Fannie Mae CLT Rider Compliance Guidance Issued September 26, 2014

Fannie Mae CLT Rider Compliance Guidance Issued September 26, 2014 This guidance applies to residential properties in community land trusts, where the homeowner’s first mortgage loan was originated to be sold to Fannie Mae. These properties can be identified by those with an executed Fannie Mae Form 2100 “Community Land Trust Ground Lease Rider” (the Rider) between the CLT (the “Lessor”) and homeowner (the “Lessee”). The Lender (the “Specified Mortgagee” or its successors or assignees) is defined as the entity that has an interest secured by a mortgage or deed of trust in the leased land and the improvements (the “Leased Premises”). This guidance intends to provide practitioners with easy-to-understand answers to common questions or events that may arise post-purchase in order to ensure compliance with the Rider. NOTE: This guidance does not comprehensively review the Rider, nor does it replace the potential need to seek legal assistance or interpretation of the Rider. Key of Terms: Rider Fannie Mae Form 2100: Community Land Trust Ground Lease Rider CLT Lessor Homeowner Lessee Lender Specified Mortgagee, its successors or assignees Leased Land + Improvements Leased Premises Glossary of Questions: 1. My CLT plans to increase the ground lease payment on the property. What do I need to do? 2. My CLT wants to modify the ground lease for an existing homeowner. What do I need to do? 3. Who needs to be listed on insurance policies? 4. The homeowner wants to sublet the home. What can the CLT allow? 5. The homeowner wants to make an addition or improvement to the property. -

Mortgage Servicers

Illinois Department of Financial and Professional Regulation Division of Financial Institutions JB PRITZKER DEBORAH HAGAN Governor Secretary CHASSE REHWINKEL Director Division of Banking March 30, 2020 Guidance to Illinois-Licensed Mortgage Servicers and Exempt Mortgage Servicers Urging Support for Borrowers Impacted by COVID-19, Including 90-Day Forbearance The COVID-19 pandemic presents many challenges for mortgage servicers and borrowers. The pandemic will continue to cause serious financial hardship for borrowers and their families, especially for those who do not have access to paid leave, have their hours reduced, or lose their jobs during this time of economic dislocation. During this challenging period, the Illinois Department of Financial and Professional Regulation, Division of Banking and Division of Financial Institutions (the “Department”) is urging all mortgage servicers, including those licensed under the Illinois Residential Mortgage License Act of 1987 (the “Act”) and those exempt from licensing under the Act (such as banks and credit unions), to take concrete steps to alleviate the direct and indirect adverse impacts of the COVID-19 pandemic on mortgage borrowers. Servicers should identify and implement fair and prudent actions, subject to the requirements of any guarantee or insurance programs, to support those mortgage borrowers unable to make timely mortgage payments as a result of the pandemic. Federal Guidance Servicers should check regularly for updates from the federal housing agencies and government- sponsored enterprises and quickly implement any available programs to help eligible borrowers. In addition, the Department reminds servicers that they must comply with all relevant loss mitigation requirements, including, but not limited to, those contained in Regulation X under the Real Estate Settlement Procedures Act. -

CARES Act, Which Includes a Foreclosure Moratorium for Certain Loans on Single-Family Properties

Last Updated: March 30, 2020 COVID-19 Crisis FORECLOSURE PROTECTION AND MORTGAGE PAYMENT RELIEF FOR HOMEOWNERS Since March 18, 2020, there have been a series of official actions relating to relief for mortgage borrowers, and we expect further actions in coming days and weeks. This informational sheet summarizes the most current information about these measures available as of the date listed above. Please note that this document only covers actions taken with regard to mortgages on single-family (1-4 unit) properties and does not cover actions taken with regard to mortgages on multifamily (i.e., more than 4-unit) properties or the details of the federal eviction moratorium. First, it is important to know that the federal actions taken so far do not apply to all mortgages on single-family properties. Of all outstanding single-family mortgages, roughly 70% are owned or backed by a federal agency, and about 30% (roughly 14.5 million loans) are privately owned and not backed by any federal agency. The federal actions so far only apply to federally-owned or -backed loans. Some financial institutions and some states have announced different types of mortgage relief for homeowners that do apply to borrowers with privately- owned mortgages, but those measures are not necessarily consistent with the new federal measures.1 It is therefore very important to determine what type of a loan a borrower has in order to understand what protections and options are available. Tools for Determining What Type of Loan a Borrower Has Fannie Mae/Freddie Mac ("GSE") - use loan look-up tools for Fannie Mae here or for Freddie Mac here. -

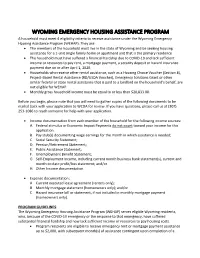

Wyoming Emergency Housing Assistance Program

WYOMING EMERGENCY HOUSING ASSISTANCE PROGRAM A household must meet 4 eligibility criteria to receive assistance under the Wyoming Emergency Housing Assistance Program (WEHAP). They are: • The members of the household must live in the state of Wyoming and be seeking housing assistance for a 1-unit single family home or apartment unit that is the primary residence. • The household must have suffered a financial hardship due to COVID-19 and lack sufficient income or resources to pay rent, a mortgage payment, a security deposit or hazard insurance payment due on or after April 1, 2020. • Households who receive other rental assistance, such as a Housing Choice Voucher (Section 8), Project-Based Rental Assistance (RD/USDA Voucher), Emergency Solutions Grant or other similar federal or state rental assistance that is paid to a landlord on the household’s behalf, are not eligible for WEHAP. • Monthly gross household income must be equal to or less than $20,833.00. Before you begin, please note that you will need to gather copies of the following documents to be mailed back with your application to WCDA for review. If you have questions, please call us at (307) 253-1086 to reach someone for help with your application. • Income documentation from each member of the household for the following income sources: A. Federal stimulus or Economic Impact Payments do not count toward your income for this application. B. Pay stub(s) documenting wage earnings for the month in which assistance is needed; C. Social Security Statement; D. Pension/Retirement Statement; E. Public Assistance Statement; F. -

Mortgage Closing Checklist

Your mortgage closing checklist Closing is the final and likely most important stage of your homebuying journey. This checklist will help you prepare and learn what to expect so you can close with confidence. Be a savvy homebuyer § Prepare in advance. Your closing is when you legally commit to your mortgage loan. Know what to plan for so everything goes smoothly. § Don’t rush. Make sure you’re getting what you expected. CFPB’s Buying a House tool § When in doubt, ask! Ask questions until you feel comfortable with every detail. www.consumerfinance.gov/buying-a-house § Beware of mortgage closing scams. Protect your life savings by knowing what to look for and how to avoid it happening to you. § Trust your gut. If something feels wrong, speak up and know that walking away may be better than signing a bad deal. Consumer Financial Learn more at consumerfinance.gov/buying-a-house. 1 of 6 Protection Bureau MORTGAGE CLOSING CHECKLIST Before closing Taking a few key actions can make your home closing go more smoothly. Use this worksheet to prepare in advance. 1. Determine who will Who will be conducting my closing? What is their title? conduct your closing, Name: where it will be, and Phone: when. ¨ Title agent ¨ Escrow agent Although the type of ¨ Closing attorney ¨ Other company conducting your closing can vary based on When is my closing? Where is my closing? where you live, you can shop for the company of Date: Time: your choice. Address: 2. Ask the person who What do I need to bring to my closing? will conduct your ¨ Review the list on page 4 and make any necessary changes. -

MORTGAGE FRAUD FACT SHEET for Victims

MORTGAGE FRAUD FACT SHEET For Victims NATIONAL CRIME PREVENTION COUNCIL Introduction various resources available to assist victims. Mortgage fraud is a crime that hurts homeowners, families, communities, businesses, and the What Is Mortgage Fraud? economy. According to the FBI’s 2010 Mortgage Fraud Report Year The FBI describes mortgage fraud in Review (August 2011), mortgage as the employment of “some fraud schemes continue to escalate. type of material misstatement, Although new laws and protections misrepresentation, or omission have been enacted to address these relating to a real estate transaction, scams, mortgage fraud schemes which is relied on by one or more have been particularly resilient and parties to the transaction.” Mortgage have adapted to economic changes fraud schemes are varied, but and modifications in lending include practices. While total losses directly attributable to mortgage fraud are 77 Foreclosure rescue schemes unknown, there is no doubt actual 77 Loan modification schemes damages are significant. CoreLogic 77 Illegal property flipping estimates reported by the FBI 77 Builder bailout/condo conversion indicate annual losses more than 77 Equity skimming $10 billion. In 2011 alone the FBI 77 Silent second received 93,508 suspicious activity 77 Home equity conversion reports relating to mortgage fraud, mortgage totaling more than $3 billion in 77 Commercial real estate loans losses (www.fbi.gov). 77 Air loans An individual who knows or is a victim of mortgage fraud should The perpetrators of mortgage understand what mortgage fraud fraud schemes include licensed/ entails, strategies victims should registered and non-licensed/ employ to protect themselves registered mortgage brokers, from further harm, and the lenders, appraisers, underwriters, a MORTGAGE FRAUD FACT SHEET FOR VICTIMS accountants, real estate agents, 77 The company/person pressured STEP 2 – Speak with a HUD- settlement attorneys, land you to sign over the deed to your approved housing counselor.