Observing Bright Nebulae

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Exploring Pulsars

High-energy astrophysics Explore the PUL SAR menagerie Astronomers are discovering many strange properties of compact stellar objects called pulsars. Here’s how they fit together. by Victoria M. Kaspi f you browse through an astronomy book published 25 years ago, you’d likely assume that astronomers understood extremely dense objects called neutron stars fairly well. The spectacular Crab Nebula’s central body has been a “poster child” for these objects for years. This specific neutron star is a pulsar that I rotates roughly 30 times per second, emitting regular appar- ent pulsations in Earth’s direction through a sort of “light- house” effect as the star rotates. While these textbook descriptions aren’t incorrect, research over roughly the past decade has shown that the picture they portray is fundamentally incomplete. Astrono- mers know that the simple scenario where neutron stars are all born “Crab-like” is not true. Experts in the field could not have imagined the variety of neutron stars they’ve recently observed. We’ve found that bizarre objects repre- sent a significant fraction of the neutron star population. With names like magnetars, anomalous X-ray pulsars, soft gamma repeaters, rotating radio transients, and compact Long the pulsar poster child, central objects, these bodies bear properties radically differ- the Crab Nebula’s central object is a fast-spinning neutron star ent from those of the Crab pulsar. Just how large a fraction that emits jets of radiation at its they represent is still hotly debated, but it’s at least 10 per- magnetic axis. Astronomers cent and maybe even the majority. -

Reconsidering the Identification of M101 Hypernova Remnant

Reconsidering the Identification of M101 Hypernova Remnant Candidates S. L. Snowden1,2, K. Mukai1,3, and W. Pence4 Code 662, NASA/Goddard Space Flight Center, Greenbelt, MD 20771 and K. D. Kuntz5 Joint Center for Astrophysics, University of Maryland Baltimore County, Baltimore, MD, 21250 ABSTRACT Using a deep Chandra AO-1 observation of the face-on spiral galaxy M101, we examine three of five previously optically-identified X-ray sources which are spatially correlated with optical supernova remnants (MF54, MF57, and MF83). The X-ray fluxes from these objects, if due to diffuse emission from the remnants, are bright enough to require a new class of objects, with the possible attribution by Wang to diffuse emission from hypernova remnants. Of the three, MF83 was considered the most likely candidate for such an object due to its size, nature, and close positional coincidence. However, we find that MF83 is clearly ruled out as a hypernova remnant by both its temporal variability and spectrum. The bright X-ray sources previously associated with MF54 and MF57 are seen by Chandra to be clearly offset from the optical positions of the supernova remnants by several arc seconds, confirming a result suggested by the previous work. MF54 does have a faint X-ray counterpart, however, with a luminosity and temperature consistent with a normal supernova remnant of its size. The most likely classifications of the sources are as X-ray binaries. Although counting statistics are limited, over the 0.3–5.0 keV spectral band the data are well fit by simple absorbed power laws with luminosities in the 1038 − 1039 ergs s−1 range. -

A Basic Requirement for Studying the Heavens Is Determining Where In

Abasic requirement for studying the heavens is determining where in the sky things are. To specify sky positions, astronomers have developed several coordinate systems. Each uses a coordinate grid projected on to the celestial sphere, in analogy to the geographic coordinate system used on the surface of the Earth. The coordinate systems differ only in their choice of the fundamental plane, which divides the sky into two equal hemispheres along a great circle (the fundamental plane of the geographic system is the Earth's equator) . Each coordinate system is named for its choice of fundamental plane. The equatorial coordinate system is probably the most widely used celestial coordinate system. It is also the one most closely related to the geographic coordinate system, because they use the same fun damental plane and the same poles. The projection of the Earth's equator onto the celestial sphere is called the celestial equator. Similarly, projecting the geographic poles on to the celest ial sphere defines the north and south celestial poles. However, there is an important difference between the equatorial and geographic coordinate systems: the geographic system is fixed to the Earth; it rotates as the Earth does . The equatorial system is fixed to the stars, so it appears to rotate across the sky with the stars, but of course it's really the Earth rotating under the fixed sky. The latitudinal (latitude-like) angle of the equatorial system is called declination (Dec for short) . It measures the angle of an object above or below the celestial equator. The longitud inal angle is called the right ascension (RA for short). -

Wind-Blown Bubbles and Hii Regions Around Massive

RevMexAA (Serie de Conferencias), 30, 64{71 (2007) WIND-BLOWN BUBBLES AND HII REGIONS AROUND MASSIVE STARS S. J. Arthur1 RESUMEN La evoluci´on de las estrellas muy masivas est´a dominada por su p´erdida de masa, aunque las tasas de p´erdida de masa no se conocen con mucha precisi´on, particularmente una vez que la estrella sale de la secuencia principal. Los estudios de las nebulosas de anillo y de las cascarones de HI que rodean a muchas estrellas Wolf-Rayet (WR) y variables azules luminosas (LBV) proporcionan algo de informaci´on acerca de la historia de la p´erdida de masa en las etapas previas. Durante la secuencia principal y la fase WR los vientos estelares hipers´onicos forman burbujas en el medio circunestelar e interestelar. Estas dos fases est´an separadas por una etapa en donde la estrella pierde masa a una tasa muy alta pero a baja velocidad. Por lo tanto, el ambiente presupernova es determinado por la estrella progenitora misma, aun´ hasta distancias de algunas decenas de parsecs de la estrella. En este art´ıculo, se describen las diferentes etapas en la evoluci´on del medio circunestelar alrededar de una estrella de masa 40 M mediante simulaciones num´ericas. ABSTRACT Mass loss dominates the evolution of very massive stars, although the mass loss rates are not known exactly, particularly once the star has left the main sequence. Studies of the ring nebulae and HI shells that surround many Wolf-Rayet (WR) and luminous blue variable (LBV) stars provide some information on the previous mass-loss history. -

Ghost Supernova Remnants: Evidence for Pulsar Reactivation in Dusty Molecular Clouds?

Notas de Rsica NOTAS DE FÍSICA é uma pré-publicaçáo de trabalhos em Física do CBPF NOTAS DE FÍSICA is a series of preprints from CBPF Pedidos de cópias desta publicaçáfo devem ser enviados aos autores ou à: Requests for free copies of these reports should be addressed to: Divisão de Publicações do CBPF-CNPq Av. Wenceslau Braz, 71 • Fundos 22.290 - Rk> de Janeiro - RJ. Brasil CBPF-NF-034/83 GHOST SUPERNOVA RE WANTS: EVIDENCE FOR PULSAR REACTIVATION IN DUSTY MOLECULAR CLOUDS? by H.Heintzmann1 and M.Novello Centro Brasileiro de Pesquisas Físicas - CBPF/CNPq Rua Xavier Sigaud, 150 22290 - R1o de Janeiro, RJ - Brasil Mnstitut fOr Theoretische Physik der UniversUlt zu K0Tn, 5000 K01n 41, FRG Alemanha GHOST SUPERNOVA REMNANTS: EVIDENCE FOR PULSAR REACTIVATION IN DUSTY MOLECULAR CLOUDS? There is ample albeit ambiguous evidence in favour of a new model for pulsar evolution, according to which pulsars aay only function as regularly pulsed emitters if an accretion disc provides a sufficiently continuous return-current to the radio pulsar (neutron star). On its way through the galaxy the pulsar will consume the disc within some My and travel further (away from the galactic plane) some 100 My without functioning as a pulsar. Back to the galactic plane it may collide with a dense molecular cloud and turn-on for some ten thousand years as a RSntgen source through accretion. The response of the dusty cloud to the collision with the pulsar should resemble a super- nova remnant ("ghost supernova remnant") whereas the pulsar will have been endowed with a new disc, new angular momentum and a new magnetic field . -

Sejong Open Cluster Survey (SOS)-IV. the Young Open Clusters

Sejong Open Cluster Survey (SOS) - IV. The Young Open Clusters NGC 1624 and NGC 1931 Beomdu Lim1,5, Hwankyung Sung2, Michael S. Bessell3, Jinyoung S. Kim4, Hyeonoh Hur2, and Byeong-Gon Park1 [email protected] Received ; accepted Not to appear in Nonlearned J., 45. 1Korea Astronomy and Space Science Institute, 776 Daedeokdae-ro, Yuseong-gu, Daejeon 305-348, Korea 2Department of Astronomy and Space Science, Sejong University, 209 Neungdong-ro, arXiv:1502.00105v1 [astro-ph.SR] 31 Jan 2015 Gwangjin-gu, Seoul 143-747, Korea 3Research School of Astronomy and Astrophysics, Australian National University, MSO, Cotter Road, Weston, ACT 2611, Australia 4Steward Observatory, University of Arizona, 933 N. Cherry Ave. Tucson, AZ 85721-0065, USA 5Corresponding author, Korea Research Council of Fundamental Science & Technology Research Fellow –2– ABSTRACT Young open clusters located in the outer Galaxy provide us with an oppor- tunity to study star formation activity in a different environment from the solar neighborhood. We present a UBVI and Hα photometric study of the young open clusters NGC 1624 and NGC 1931 that are situated toward the Galactic anticenter. Various photometric diagrams are used to select the members of the clusters and to determine the fundamental parameters. NGC 1624 and NGC 1931 are, on average, reddened by hE(B − V )i = 0.92 ± 0.05 and 0.74 ± 0.17 mag, respectively. The properties of the reddening toward NGC 1931 indicate an abnormal reddening law (RV,cl = 5.2 ± 0.3). Using the zero-age main se- quence fitting method we confirm that NGC 1624 is 6.0 ± 0.6 kpc away from the Sun, whereas NGC 1931 is at a distance of 2.3 ± 0.2 kpc. -

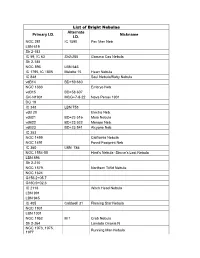

List of Bright Nebulae Primary I.D. Alternate I.D. Nickname

List of Bright Nebulae Alternate Primary I.D. Nickname I.D. NGC 281 IC 1590 Pac Man Neb LBN 619 Sh 2-183 IC 59, IC 63 Sh2-285 Gamma Cas Nebula Sh 2-185 NGC 896 LBN 645 IC 1795, IC 1805 Melotte 15 Heart Nebula IC 848 Soul Nebula/Baby Nebula vdB14 BD+59 660 NGC 1333 Embryo Neb vdB15 BD+58 607 GK-N1901 MCG+7-8-22 Nova Persei 1901 DG 19 IC 348 LBN 758 vdB 20 Electra Neb. vdB21 BD+23 516 Maia Nebula vdB22 BD+23 522 Merope Neb. vdB23 BD+23 541 Alcyone Neb. IC 353 NGC 1499 California Nebula NGC 1491 Fossil Footprint Neb IC 360 LBN 786 NGC 1554-55 Hind’s Nebula -Struve’s Lost Nebula LBN 896 Sh 2-210 NGC 1579 Northern Trifid Nebula NGC 1624 G156.2+05.7 G160.9+02.6 IC 2118 Witch Head Nebula LBN 991 LBN 945 IC 405 Caldwell 31 Flaming Star Nebula NGC 1931 LBN 1001 NGC 1952 M 1 Crab Nebula Sh 2-264 Lambda Orionis N NGC 1973, 1975, Running Man Nebula 1977 NGC 1976, 1982 M 42, M 43 Orion Nebula NGC 1990 Epsilon Orionis Neb NGC 1999 Rubber Stamp Neb NGC 2070 Caldwell 103 Tarantula Nebula Sh2-240 Simeis 147 IC 425 IC 434 Horsehead Nebula (surrounds dark nebula) Sh 2-218 LBN 962 NGC 2023-24 Flame Nebula LBN 1010 NGC 2068, 2071 M 78 SH 2 276 Barnard’s Loop NGC 2149 NGC 2174 Monkey Head Nebula IC 2162 Ced 72 IC 443 LBN 844 Jellyfish Nebula Sh2-249 IC 2169 Ced 78 NGC Caldwell 49 Rosette Nebula 2237,38,39,2246 LBN 943 Sh 2-280 SNR205.6- G205.5+00.5 Monoceros Nebula 00.1 NGC 2261 Caldwell 46 Hubble’s Var. -

Blasts from the Past Historic Supernovas

BLASTS from the PAST: Historic Supernovas 185 386 393 1006 1054 1181 1572 1604 1680 RCW 86 G11.2-0.3 G347.3-0.5 SN 1006 Crab Nebula 3C58 Tycho’s SNR Kepler’s SNR Cassiopeia A Historical Observers: Chinese Historical Observers: Chinese Historical Observers: Chinese Historical Observers: Chinese, Japanese, Historical Observers: Chinese, Japanese, Historical Observers: Chinese, Japanese Historical Observers: European, Chinese, Korean Historical Observers: European, Chinese, Korean Historical Observers: European? Arabic, European Arabic, Native American? Likelihood of Identification: Possible Likelihood of Identification: Probable Likelihood of Identification: Possible Likelihood of Identification: Possible Likelihood of Identification: Definite Likelihood of Identification: Definite Likelihood of Identification: Possible Likelihood of Identification: Definite Likelihood of Identification: Definite Distance Estimate: 8,200 light years Distance Estimate: 16,000 light years Distance Estimate: 3,000 light years Distance Estimate: 10,000 light years Distance Estimate: 7,500 light years Distance Estimate: 13,000 light years Distance Estimate: 10,000 light years Distance Estimate: 7,000 light years Distance Estimate: 6,000 light years Type: Core collapse of massive star Type: Core collapse of massive star Type: Core collapse of massive star? Type: Core collapse of massive star Type: Thermonuclear explosion of white dwarf Type: Thermonuclear explosion of white dwarf? Type: Core collapse of massive star Type: Thermonuclear explosion of white dwarf Type: Core collapse of massive star NASA’s ChANdrA X-rAy ObServAtOry historic supernovas chandra x-ray observatory Every 50 years or so, a star in our Since supernovas are relatively rare events in the Milky historic supernovas that occurred in our galaxy. Eight of the trine of the incorruptibility of the stars, and set the stage for observed around 1671 AD. -

SAC's 110 Best of the NGC

SAC's 110 Best of the NGC by Paul Dickson Version: 1.4 | March 26, 1997 Copyright °c 1996, by Paul Dickson. All rights reserved If you purchased this book from Paul Dickson directly, please ignore this form. I already have most of this information. Why Should You Register This Book? Please register your copy of this book. I have done two book, SAC's 110 Best of the NGC and the Messier Logbook. In the works for late 1997 is a four volume set for the Herschel 400. q I am a beginner and I bought this book to get start with deep-sky observing. q I am an intermediate observer. I bought this book to observe these objects again. q I am an advance observer. I bought this book to add to my collect and/or re-observe these objects again. The book I'm registering is: q SAC's 110 Best of the NGC q Messier Logbook q I would like to purchase a copy of Herschel 400 book when it becomes available. Club Name: __________________________________________ Your Name: __________________________________________ Address: ____________________________________________ City: __________________ State: ____ Zip Code: _________ Mail this to: or E-mail it to: Paul Dickson 7714 N 36th Ave [email protected] Phoenix, AZ 85051-6401 After Observing the Messier Catalog, Try this Observing List: SAC's 110 Best of the NGC [email protected] http://www.seds.org/pub/info/newsletters/sacnews/html/sac.110.best.ngc.html SAC's 110 Best of the NGC is an observing list of some of the best objects after those in the Messier Catalog. -

Atlas Menor Was Objects to Slowly Change Over Time

C h a r t Atlas Charts s O b by j Objects e c t Constellation s Objects by Number 64 Objects by Type 71 Objects by Name 76 Messier Objects 78 Caldwell Objects 81 Orion & Stars by Name 84 Lepus, circa , Brightest Stars 86 1720 , Closest Stars 87 Mythology 88 Bimonthly Sky Charts 92 Meteor Showers 105 Sun, Moon and Planets 106 Observing Considerations 113 Expanded Glossary 115 Th e 88 Constellations, plus 126 Chart Reference BACK PAGE Introduction he night sky was charted by western civilization a few thou - N 1,370 deep sky objects and 360 double stars (two stars—one sands years ago to bring order to the random splatter of stars, often orbits the other) plotted with observing information for T and in the hopes, as a piece of the puzzle, to help “understand” every object. the forces of nature. The stars and their constellations were imbued with N Inclusion of many “famous” celestial objects, even though the beliefs of those times, which have become mythology. they are beyond the reach of a 6 to 8-inch diameter telescope. The oldest known celestial atlas is in the book, Almagest , by N Expanded glossary to define and/or explain terms and Claudius Ptolemy, a Greco-Egyptian with Roman citizenship who lived concepts. in Alexandria from 90 to 160 AD. The Almagest is the earliest surviving astronomical treatise—a 600-page tome. The star charts are in tabular N Black stars on a white background, a preferred format for star form, by constellation, and the locations of the stars are described by charts. -

Supernova Remnant N103B, Radio Pulsar B1951+32, and the Rabbit

On Understanding the Lives of Dead Stars: Supernova Remnant N103B, Radio Pulsar B1951+32, and the Rabbit by Joshua Marc Migliazzo Bachelor of Science, Physics (2001) University of Texas at Austin Submitted to the Department of Physics in partial fulfillment of the requirements for the degree of Master of Science in Physics at the MASSACHUSETTS INSTITUTE OF TECHNOLOGY February 2003 c Joshua Marc Migliazzo, MMIII. All rights reserved. The author hereby grants to MIT permission to reproduce and distribute publicly paper and electronic copies of this thesis document in whole or in part. Author.............................................................. Department of Physics January 17, 2003 Certifiedby.......................................................... Claude R. Canizares Associate Provost and Bruno Rossi Professor of Physics Thesis Supervisor Accepted by . ..................................................... Thomas J. Greytak Chairman, Department Committee on Graduate Students 2 On Understanding the Lives of Dead Stars: Supernova Remnant N103B, Radio Pulsar B1951+32, and the Rabbit by Joshua Marc Migliazzo Submitted to the Department of Physics on January 17, 2003, in partial fulfillment of the requirements for the degree of Master of Science in Physics Abstract Using the Chandra High Energy Transmission Grating Spectrometer, we observed the young Supernova Remnant N103B in the Large Magellanic Cloud as part of the Guaranteed Time Observation program. N103B has a small overall extent and shows substructure on arcsecond spatial scales. The spectrum, based on 116 ks of data, reveals unambiguous Mg, Ne, and O emission lines. Due to the elemental abundances, we are able to tentatively reject suggestions that N103B arose from a Type Ia supernova, in favor of the massive progenitor, core-collapse hypothesis indicated by earlier radio and optical studies, and by some recent X-ray results. -

Astronomy General Information

ASTRONOMY GENERAL INFORMATION HERTZSPRUNG-RUSSELL (H-R) DIAGRAMS -A scatter graph of stars showing the relationship between the stars’ absolute magnitude or luminosities versus their spectral types or classifications and effective temperatures. -Can be used to measure distance to a star cluster by comparing apparent magnitude of stars with abs. magnitudes of stars with known distances (AKA model stars). Observed group plotted and then overlapped via shift in vertical direction. Difference in magnitude bridge equals distance modulus. Known as Spectroscopic Parallax. SPECTRA HARVARD SPECTRAL CLASSIFICATION (1-D) -Groups stars by surface atmospheric temp. Used in H-R diag. vs. Luminosity/Abs. Mag. Class* Color Descr. Actual Color Mass (M☉) Radius(R☉) Lumin.(L☉) O Blue Blue B Blue-white Deep B-W 2.1-16 1.8-6.6 25-30,000 A White Blue-white 1.4-2.1 1.4-1.8 5-25 F Yellow-white White 1.04-1.4 1.15-1.4 1.5-5 G Yellow Yellowish-W 0.8-1.04 0.96-1.15 0.6-1.5 K Orange Pale Y-O 0.45-0.8 0.7-0.96 0.08-0.6 M Red Lt. Orange-Red 0.08-0.45 *Very weak stars of classes L, T, and Y are not included. -Classes are further divided by Arabic numerals (0-9), and then even further by half subtypes. The lower the number, the hotter (e.g. A0 is hotter than an A7 star) YERKES/MK SPECTRAL CLASSIFICATION (2-D!) -Groups stars based on both temperature and luminosity based on spectral lines.