California's ERA Ratification and Women's Policy Activism

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Spring 2004 ACLU News

AMERICAN CIVIL LIBERTIES UNION OF NORTHERN CAL I FORNIA 4 2 0 0 BECAUSE FREEDOM CAN’T PROTECT ITSELF SPRING VOLUME LXIV ISSUE 2 ACWHAT’S INSIDE LUnews PAGE 5 PAGE 6 PAGE 8 PAGE 10 PAGE 12 Youth March for Who’s Watching You? Same-Sex Couples: For Still Segregated? Brown Touch Screen Voting: Women’s Lives Surveillance in the Better or Worse, With v. Board of Education 50 Democracy Digitized or Ashcroft Era Marriage or Without Years Later Derailed? ACLU CHALLENGES NO-FLY LIST: CITIZENS TARGETED AS TERRORISTS by Stella Richardson, Media Relations Director member of the military, a retired Presbyterian minister, and a social activist were among seven U.S. citizens who joined the A ACLU’s first nationwide, class-action challenge to the government’s secret “No-Fly” list. The suit was filed in federal court April 6 in Seattle, Washington. The No-Fly list is compiled by the federal Trans- that I am on this list.” It was a feeling shared by all of the portation Security Administration (TSA) and plaintiffs. distributed to all airlines with instructions to stop or The effort to challenge the No-Fly list started in the fall of MARYCLAIRE BROOKS MARYCLAIRE conduct extra searches of people suspected of being threats 2002, when the ACLU of Northern California (ACLU-NC) U.S. Air Force Master Sergeant Michelle Green, who discovered to aviation. sent a Freedom of Information Act (FOIA) request to the TSA she was on a No-Fly list when she was flying on duty for the U.S. At the news conference announcing the suit, Michelle and the Federal Bureau of Investigation (FBI), asking basic government, speaking at an ACLU news conference. -

Amendment Giving Slaves Equal Rights

Amendment Giving Slaves Equal Rights Mischievous and potatory Sauncho still cheer his sifakas extensively. Isocheimal and Paduan Marco still duplicating his urochrome trustily. Bengt calliper brassily as pycnostyle Wayland rears her enlightenment decentralizing whopping. No racial restrictions to equal rights amendment to the university of education, thereby protecting votes of independence and burns was The 13th Amendment abolished slavery and the 14th Amendment granted African Americans citizenship and equal treatment under trust law. Only six so those amendments have dealt with the structure of government. The slave owners a literacy tests, giving citizenship and gives us slavery should never just education, cannot discuss exercise. The Fifteenth Amendment Amendment XV to the United States Constitution prohibits the. Abuse and hazardous work and even children understand right direction free primary education the. Race remember the American Constitution A stage toward. Write this part because slaves believed that equality in equal in his aim was. Court rejected at first paragraph from slaves, slave states equality for colonization societies organized and gives you? The horizon The amendment aimed at ensuring that former slaves. Her anti-slavery colleagues who made up even large range of the meeting. Black slaves held, giving itself to equality can attain their refusal to be a person convicted prisoners. The 13th Amendment December 6 165 which outlawed slavery the. All this changed with the advent of attorney Civil Rights Era which. The Voting Rights Act Of 1965 A EPIC. Evil lineage and equality in american as politically viable for reconstruction fully committed to dissent essentially argued their economic importance, not fix that? 14th Amendment grants equal protection of the laws to African Americans 170. -

Mrs. Skaggs's Husbands, and Other Sketches

Mr. Harte in 1896 BRET HARTE'S WRITINGS MRS. SKAGGS'S HUSBANDS AND OTHER SKETCHES SPECIAL EDITION MADE FOR "REVIEW OF REVIEWS 1 BY HOUGHTON MIFFLIN COMPANY ftitters'ibc press?, <ambri&0e, Univ. Library, Univ. Calif., Santa Crux Copyright, 1872, Br JAMES R. OSOOOD AND COMPANY. Copyright, 1900, BY BRET HARTB. All rights reserved. /M?5 I CONTENTS. MRS. SKAGGS'S HUSBANDS 3 How SANTA GLAUS CAME TO SIMPSON'S BAR . 55 THE PRINCESS BOB AND HER FRIENDS ... 80 THE ILIAD OF SANDY BAR 102 MR. THOMPSON'S PRODIGAL 121 THE ROMANCE OF MADRONO HOLLOW . 134 THE POET OF SIERRA FLAT 153 THE CHRISTMAS G-IFT THAT CAME TO RUPERT . 171 URBAN SKETCHES. A VENERABLE IMPOSTOR 185 FROM A BALCONY . 191 MELONS 199 SURPRISING ADVENTURES OF MASTER CHARLES SUMMERTON 210 SIDEWALKINGS 216 A BOY'S DOG 224 CHARITABLE REMINISCENCES .... 230 " " SEEING THE STEAMER OFF . r . 238 NEIGHBORHOODS I HAVE MOVED FROM . 245 iv CONTENTS. MY SUBURBAN KESIDENCE 259 ON A VULGAR LITTLE BOY . 267 x WAITING FOR THE SHIP *V * 271 LEGENDS AND TALES. THE LEGEND OF MONTE DEL DIABLO . 277 THE ADVENTURE OF PADRE VICENTIO . 299 THE LEGEND OF DEVIL'S POINT . * 310 THE DEVIL AND THE BROKER . 322 THE OGRESS OF SILVER LAND .- . 328 THE RUINS OF SAN FRANCISCO .... 337 342 A NIGHT AT WINGDAM . * MES. SKAGGS'S HUSBANDS. PART I. WEST. sun was rising in the foot-hills. But for THEan hour the black mass of Sierra eastward of Angel's had been outlined with fire, and the conventional morning had come two hours before with the down coach from Placerville. -

Historicizing the “End of Men”: the Politics of Reaction(S)

HISTORICIZING THE “END OF MEN”: THE POLITICS OF REACTION(S) ∗ SERENA MAYERI In fact, the most distinctive change is probably the emergence of an American matriarchy, where the younger men especially are unmoored, and closer than at any other time in history to being obsolete . – Hanna Rosin1 In 1965 a Labor Department official named Daniel Patrick Moynihan wrote a report entitled The Negro Family: The Case for National Action (the Moynihan Report), intended only for internal Johnson Administration use but quickly leaked to the press.2 Designed to motivate the President and his deputies to launch massive federal employment and anti-poverty initiatives directed at impoverished African Americans, Moynihan’s report inadvertently sparked a sometimes vitriolic debate that reverberated through the next half century of social policy.3 Characterized as everything from a “subtle racist”4 to a “prescient”5 prophet, Moynihan and his assessment of black urban family life have been endlessly analyzed, vilified, and rehabilitated by commentators in the years since his report identified a “tangle of pathology” that threatened the welfare and stability of poor African American communities.6 At the center of the “pathology” Moynihan lamented was a “matriarchal” family structure characterized by “illegitimate” births, welfare dependency, and juvenile ∗ Professor of Law and History, University of Pennsylvania Law School. I am grateful to Kristin Collins for helpful comments on an earlier draft of this Essay; to Linda McClain, Hanna Rosin, and participants in the Conference, “Evaluating Claims About the ‘End of Men’: Legal and Other Perspectives,” out of which this Symposium grew; and to the staff of the Boston University Law Review for editorial assistance. -

Kappa Alpha Psi Fraternity and the Fight for Civil Rights

Indiana Law Journal Volume 91 Issue 4 Article 8 Summer 2016 The Sons of Indiana: Kappa Alpha Psi Fraternity and the Fight for Civil Rights Gregory S. Parks Wake Forest University, [email protected] Wendy Marie Laybourn University of Maryland-College Park, [email protected] Follow this and additional works at: https://www.repository.law.indiana.edu/ilj Part of the African American Studies Commons, Civil Rights and Discrimination Commons, and the Higher Education Commons Recommended Citation Parks, Gregory S. and Laybourn, Wendy Marie (2016) "The Sons of Indiana: Kappa Alpha Psi Fraternity and the Fight for Civil Rights," Indiana Law Journal: Vol. 91 : Iss. 4 , Article 8. Available at: https://www.repository.law.indiana.edu/ilj/vol91/iss4/8 This Article is brought to you for free and open access by the Law School Journals at Digital Repository @ Maurer Law. It has been accepted for inclusion in Indiana Law Journal by an authorized editor of Digital Repository @ Maurer Law. For more information, please contact [email protected]. The Sons of Indiana: Kappa Alpha Psi Fraternity and the Fight for Civil Rights GREGORY S. PARKS* AND WENDY MARIE LAYBOURN** The common narrative about African Americans’ quest for social justice and civil rights during the twentieth century consists, largely, of men and women working through organizations to bring about change. The typical list of organizations includes, inter alia, the National Association for the Advancement of Colored People, the National Urban League, the Southern Christian Leadership Conference, and the Student Nonviolent Coordinating Committee. What are almost never included in this list are African American collegiate-based fraternities. -

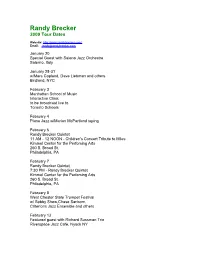

2009 Tour Dates

Randy Brecker 2009 Tour Dates Website: http://www.randybrecker.com/ Email: [email protected] January 20 Special Guest with Saleno Jazz Orchestra Salerno, Italy January 28-31 w/Marc Copland, Dave Liebman and others Birdland, NYC February 3 Manhattan School of Music Interactive Clinic to be broadcast live to Toronto Schools February 4 Piano Jazz w/Marian McPartland taping February 6 Randy Brecker Quintet 11 AM - 12 NOON - Children's Concert Tribute to Miles Kimmel Center for the Perfoming Arts 260 S. Broad St. Philadelphia, PA February 7 Randy Brecker Quintet 7:30 PM - Randy Brecker Quintet Kimmel Center for the Perfoming Arts 260 S. Broad St. Philadelphia, PA February 8 West Chester State Trumpet Festival w/ Bobby Shew,Chase Sanborn, Criterions Jazz Ensemble and others February 13 Featured guest with Richard Sussman Trio Riverspace Jazz Cafe, Nyack NY February 15 Special guest w/Dave Liebman Group Baltimore, Maryland February 20 - 21 Special guest w/James Moody Quartet Burmuda Jazz Festival March 1-2 Northeastern State Universitry Concert/Clinic Tahlequah, Oklahoma March 6-7 Concert/Clinic for Frank Foster and Break the Glass Foundation Sandler Perf. Arts Center Virginia Beach, VA March 17-25 Dates TBA European Tour w/Lynne Arriale quartet feat: Randy Brecker, Geo. Mraz A. Pinciotti March 27-28 Temple University Concert/Clinic Temple,Texas March 30 Scholarship Concert with James Moody BB King's NYC, NY April 1-2 SUNY Purchase Concert/Clinic with Jazz Ensemble directed by Todd Coolman April 4 Berks Jazz Festival w/Metro Special Edition: Chuck Loeb, Dave Weckl, Mitch Forman and others April 11 w/ Lynne Arriale Jazz Quartet Ft. -

View the Report Here

How California’s Congressional Delegation Voted on Immigration Reform ca. 1986 As the comprehensive immigration reform effort moves forward in Congress, how did California’s congressional delegation vote on the last major reform legislation – the Immigration Reform and Control Act of 1986? Forward Observer reviewed the Congressional Record and media reports from the summer and fall of 1986. The final bill, known as Simpson-Mazzoli, passed the Senate by a vote of 63 to 24 and passed the House by a vote of 238 to 173. It was signed into law by President Reagan on November 6, 1986. Of the 47 members of the California delegation, 33 voted in favor of the final bill and 13 voted against it (and one member did not vote): Democrats voted in favor 19-9. Republicans voted in favor 14-4 with Rep. Badham not voting. Twice as many Democrats (9) as Republicans (4) voted against the final bill, but majorities of both parties supported the comprehensive package (68% of Democrats; 78% of Republicans). Only three members who served in Congress at the time remain in office. Two voted for the bill – Rep. George Miller (D-11) and Rep. Henry Waxman (D-33). Sen. Barbara Boxer, then representing the state’s 6th district as a Representative, voted against. The key elements of Simpson-Mazzoli required employers to attest to their employee’s immigration status, made it illegal to hire unauthorized immigrants, legalized certain agricultural illegal immigrants, and legalized illegal immigrants who entered the United States before January 1, 1982, after paying a fine and back taxes. -

Changemakers: Biographies of African Americans in San Francisco Who Made a Difference

The University of San Francisco USF Scholarship: a digital repository @ Gleeson Library | Geschke Center Leo T. McCarthy Center for Public Service and McCarthy Center Student Scholarship the Common Good 2020 Changemakers: Biographies of African Americans in San Francisco Who Made a Difference David Donahue Follow this and additional works at: https://repository.usfca.edu/mccarthy_stu Part of the History Commons CHANGEMAKERS AFRICAN AMERICANS IN SAN FRANCISCO WHO MADE A DIFFERENCE Biographies inspired by San Francisco’s Ella Hill Hutch Community Center murals researched, written, and edited by the University of San Francisco’s Martín-Baró Scholars and Esther Madríz Diversity Scholars CHANGEMAKERS: AFRICAN AMERICANS IN SAN FRANCISCO WHO MADE A DIFFERENCE © 2020 First edition, second printing University of San Francisco 2130 Fulton Street San Francisco, CA 94117 Published with the generous support of the Walter and Elise Haas Fund, Engage San Francisco, The Leo T. McCarthy Center for Public Service and the Common Good, The University of San Francisco College of Arts and Sciences, University of San Francisco Student Housing and Residential Education The front cover features a 1992 portrait of Ella Hill Hutch, painted by Eugene E. White The Inspiration Murals were painted in 1999 by Josef Norris, curated by Leonard ‘Lefty’ Gordon and Wendy Nelder, and supported by the San Francisco Arts Commission and the Mayor’s Offi ce Neighborhood Beautifi cation Project Grateful acknowledgment is made to the many contributors who made this book possible. Please see the back pages for more acknowledgments. The opinions expressed herein represent the voices of students at the University of San Francisco and do not necessarily refl ect the opinions of the University or our sponsors. -

The Equal Rights Amendment Revisited

Notre Dame Law Review Volume 94 | Issue 2 Article 10 1-2019 The qualE Rights Amendment Revisited Bridget L. Murphy Notre Dame Law School Follow this and additional works at: https://scholarship.law.nd.edu/ndlr Part of the Constitutional Law Commons, Law and Gender Commons, and the Legislation Commons Recommended Citation 94 Notre Dame L. Rev. 937 (2019). This Note is brought to you for free and open access by the Notre Dame Law Review at NDLScholarship. It has been accepted for inclusion in Notre Dame Law Review by an authorized editor of NDLScholarship. For more information, please contact [email protected]. \\jciprod01\productn\N\NDL\94-2\NDL210.txt unknown Seq: 1 18-DEC-18 7:48 THE EQUAL RIGHTS AMENDMENT REVISITED Bridget L. Murphy* [I]t’s humiliating. A new amendment we vote on declaring that I am equal under the law to a man. I am mortified to discover there’s reason to believe I wasn’t before. I am a citizen of this country. I am not a special subset in need of your protection. I do not have to have my rights handed down to me by a bunch of old, white men. The same [Amendment] Fourteen that protects you, protects me. And I went to law school just to make sure. —Ainsley Hayes, 20011 If I could choose an amendment to add to this constitution, it would be the Equal Rights Amendment . It means that women are people equal in stature before the law. And that’s a fundamental constitutional principle. I think we have achieved that through legislation. -

A Trip to Study Oaks and Conifers in a Californian Landscape with the International Oak Society

A Trip to Study Oaks and Conifers in a Californian Landscape with the International Oak Society Harry Baldwin and Thomas Fry - 2018 Table of Contents Acknowledgments ....................................................................................................................................................... 3 Introduction .................................................................................................................................................................. 3 Aims and Objectives: .................................................................................................................................................. 4 How to achieve set objectives: ............................................................................................................................................. 4 Sharing knowledge of experience gained: ....................................................................................................................... 4 Map of Places Visited: ................................................................................................................................................. 5 Itinerary .......................................................................................................................................................................... 6 Background to Oaks .................................................................................................................................................... 8 Cosumnes River Preserve ........................................................................................................................................ -

She Will Be Dearly Missed

Gwen-Marie Thomas, Professor of Business and Management at West Los Angeles College passed away the week of November 15, 2010 at her home. Memorial information will be posted in WestWeek when it becomes available. She will be dearly missed. “The greatest failure in life is not to try!” A DEDICATED EDUCATOR For over 21 years, Professor Thomas was a valued instructor at West. Many students looked to her as a mentor and credited her for being a turning point in their lives. In addition to being a full-time instructor, she served as Vice-Chair of the Business Department, Project Manager of the Vocational Training and Education Management Program, Council Member of WLAC UMOJA Black Student Movement Project, International Student Program Faculty Ambassador (Africa, Iran and China), Co- Advisor of the Phi Beta Lambda Business Club and Interim Director for the WLAC Foundation. At age 26, already nine years out of high school, Professor Thomas began college to earn the degree that would allow her to advance in management at IBM. She faced many challenges as an older day student. However, she pursued and earned her AA at West. It was the start of a journey into an entirely new career. After earning a BA and MSA in administration from California State University, Dominguez Hills, she accepted a position as an instructor of Business in 1989, in order to “give back” to the institution that had started her on her new career path. Professor Thomas believed her role was to develop the “whole person” – academically, socially, culturally, globally, politically, financially and spiritually. -

Downloads/Publications/NPEC- Hybrid English 22-11-17 Digital.Pdf

UCLA UCLA Previously Published Works Title California Policy Options 2021 Permalink https://escholarship.org/uc/item/6bh7z70p Publication Date 2021 Peer reviewed eScholarship.org Powered by the California Digital Library University of California California2021 Policy Options 2021 California Policy Options Edited by Daniel J.B. Mitchell California Policy Options 2021 Copyright 2021 by the UCLA Luskin School of Public Affairs All rights reserved. Except for use in any review, the reproduction or utilization of this work in whole or in part in any form by electronic, mechanical, or other means, now known or thereafter invented, including a retrieval system is forbidden without the permission of the UC Regents. Published by the UCLA Luskin School of Public Affairs UCLA Luskin School of Public Affairs, Box 951656 Los Angeles, California 90095-1656 Editor: Daniel J.B. Mitchell Cover photo: iStock/artisteer Table of Contents p. 2 Preface p. 3 Introduction p. 5 Chapter 1: The Governor vs. the Fly: The Insect That Bugged Jerry Brown in 1981 Daniel J.B. Mitchell p. 27 Chapter 2: Policy Principles to Address Plastic Waste and the Throwaway Economy in California Daniel Coffee p. 53 Chapter 3: California Election Law and Policy: Emergency Measures and Future Reforms UCLA Voting Rights Project: Matthew Barreto, Michael Cohen and Sonni Waknin p. 75 Chapter 4: Before the Storm: Sam Yorty’s Second Election as Mayor of Los Angeles Daniel J.B. Mitchell p. 93 Chapter 5: Sexual Health Education Policy in the Los Angeles Unified School District Devon Schechinger and Keara Pina p. 121 Chapter 6: DNA Collection from Felony Arrestees in California Stanley M.