Attention and Blind-Spot Phenomenology

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Guess Who? Answer

Guess Who? Answer soon became interested in ophthalmology and was appointed Hansen Grut's assistant in 1879. Bjerrum's scientific concern was the relationship between visual perception of form and the resolving power in localized areas of the retina. He demonstrated this in his thesis entitled ' UndersØgeleser over Formsans og Lyssands i forskellige Øjensyngdomme (Investigations on the form sense and light sense in various eye diseases). This title is deliberately given in Danish to indicate that through his entire lifetime it was mandatory for him to write his publications in Danish. An antipathy against German, in those days the language of science, may have been gained in a childhood so filled with tension regarding nationalism. The scientific achievement that made the name Bjerrum universally known was conceived during his work on the relationship between visual acuity and the perception of the bright stimuli in various retinal zones. In accordance with his own modest attitude, this discovery was published in 1889 in a small paper which in translation was called 'An addendum to the usual examination of the visual field of glaucoma'. At that time Bjerrum was studying the visual field by means of small white objects. The idea Jannik Peterson Bjerrum of this investigation was to record the performance of every single functional unit of the retina. As a Danish ophthalmologist. Born 1851, died 1920 minimum such units in Bjerrum's opinion would subtend a visual angle of one minute of arc (in the Jannik Petersen Bjerrum was born 26th December 1851 macular region). However, even a small test object in Skarbak, a village in the most southern part of would subtend a visual angle exceeding two degrees Jutland in the border district between the Danish and accordingly cover a multitude of functional units. -

Twelfth International Visual Field Symposium

PERIMETRY UPDATE 1996/1997 PERIMETRY UPDATE 199611997 Proceedings of the Xllth International Perimetric Society Meeting Wijrzburg, Germany, June 4-8, 1996 edited by Michael Wall and Anders Heijl KUGLER PUBLICATIONS Amsterdam / New York ISBN 90-6299-139-4 Distributors For the LJ S A and Canada: DEMOS 386 Park Avenue South, Suite 201 New York, NY 10016 Telefax (+212) 683-0072 For all other countries Kugler Publications P.O. Box 11188 1001 GD Amsterdam, The Netherlands 0 Copyright 1997 Kugler Publications All rights reserved No part of this book may be translated or reproduced in any form by print, photoprint, microfilm, or any other means without prior written permission of the publisher. Table of Contents v TABLE OF CONTENTS Preface xi New methods of perimetry Contrast sensitivity perimetry in experimental glaucoma: investigations with degenerate gratings R.S. Harwerth and E.L. Smith, III 3 The role of spatial and temporal factors in frequency-doubling perimetry C.A. Johnson and S. Demirel 13 Motion detection perimetry: properties and results M. Wall, C.F. Brito and K. Kutzko 21 Stimulus orientation can affect motion sensitivity in glaucoma M.C. Westcott, F.W. Fitzke and R.A. Hitchings 35 Short-wavelength automated perimetry and motion automated perimetry in glaucoma P.A. Sample, Ch.F. Bosworth, I. Irak and R.N. Weinreb 43 Blue-on-yellow perimetry in patients with ocular hypertension H. Maeda, Y. Tanaka and T. Sugiura 45 Mass screening for visual field defects with snowfield campimetry: results of a field study using local TV broadcasting A.C. Gisolf, J. Kirsch, H.K. -

VISUAL FIELD Pathway Extends from the „Front‟ to the „Back‟ of the RETINA Brain

NOTE: To change the image on this slide, select the picture and delete it. Then click the Pictures icon in the placeholde r to insert your own image. Visual Pathway Disorders Amr Hassan, MD, FEBN Associate professor of Neurology - Cairo University Optic nerve • Anatomy of visual pathway • How to examine • Visual pathway disorders • Quiz 2 Optic nerve • Anatomy of visual pathway • How to examine • Visual pathway disorders • Quiz 3 Optic nerve The Visual Pathway VISUAL FIELD Pathway extends from the „front‟ to the „back‟ of the RETINA brain. ON OC OT LGN OPTIC RADIATIONS ON = Optic Nerve OC = Optic Chiasm OT = Optic Tract LGN = Lateral Geniculate Nucleus of Thalamus VISUAL CORTEX 5 The Visual Pathway Eyes & Retina Light >> lens >> retina (inverted and reversed image). Eyes & Retina Eyes & Retina • Macula: oval region approximately 3-5 mm that surrounds the fovea, also has high visual acuity. • Fovea: central fixation point of each eye// region of the retina with highest visual acuity. Eyes & Retina • Optic disc: region where axons leaving the retina gather to form the Optic nerve. Eyes & Retina • Blind spot located 15° lateral and inferior to central fixation point of each eye. Object to be seen Peripheral Retina Central Retina (fovea in the macula lutea) 12 Photoreceptors © Stephen E. Palmer, 2002 Photoreceptors Cones • Cone-shaped • Less sensitive • Operate in high light • Color vision • Less numerous • Highly represented in the fovea >> have high spatial & temporal resolution >> they detect colors. © Stephen E. Palmer, 2002 Photoreceptors Rods • Rod-shaped • Highly sensitive • Operate at night • Gray-scale vision • More numerous than cons- 20:1, have poor spatial & temporal resolution of visual stimuli, do not detect colors >> vision in low level lighting conditions © Stephen E. -

Functional Field of Vision

Functional Field of Vision Lea Hyvärinen Lea-Test Ltd, Apollonkatu 6 A 4, FIN-00100 Helsinki The size and the quality of visual field are important basic functions to be assessed as a part of functional vision assessment. Evaluation of functional field losses can be organized as follows: 1. Major field losses: A. Field losses due to pathway damage - half field loss, right, left remaining motion perception in ‘blind’ field half - quadrant losses B. Field losses due to disorders of the eyes - ROP - Congenital Glaucoma - Coloboma - Retinitis Pigmentosa and related disorders C. Central Scotoma 2. Minor field losses 3. Distortion of the image 4. Perceptual losses without measurable field loss 5. Restriction of functional visual field due to motor problems It may be wise to clarify some definitions: Anterior visual pathways contain eyes and the pathway up to the lateral geniculate nucleus (LGN), and posterior visual pathways contain the nerve fibres from the LGN to the primary visual cortex. Anterior visual impairment is due to damage to anterior pathways. Posterior visual impairment is due to damage to posterior visual pathways but may also be due to abnormal function in higher visual functions in the associative visual cortices without pathway damage. Information on visual field is given as drawings that depict the loss of function as it is projected onto the physical space around us. However, because central parts of visual field occupy much more cortical area in the primary visual cortex, they are magnified (= cortical magnification) in relation to the peripheral parts of the visual field (as illustrated in Figure 1). -

17-2021 CAMI Pilot Vision Brochure

Visual Scanning with regular eye examinations and post surgically with phoria results. A pilot who has such a condition could progress considered for medical certification through special issuance with Some images used from The Federal Aviation Administration. monofocal lenses when they meet vision standards without to seeing double (tropia) should they be exposed to hypoxia or a satisfactory adaption period, complete evaluation by an eye Helicopter Flying Handbook. Oklahoma City, Ok: US Department The probability of spotting a potential collision threat complications. Multifocal lenses require a brief waiting certain medications. specialist, satisfactory visual acuity corrected to 20/20 or better by of Transportation; 2012; 13-1. Publication FAA-H-8083. Available increases with the time spent looking outside, but certain period. The visual effects of cataracts can be successfully lenses of no greater power than ±3.5 diopters spherical equivalent, at: https://www.faa.gov/regulations_policies/handbooks_manuals/ techniques may be used to increase the effectiveness of treated with a 90% improvement in visual function for most One prism diopter of hyperphoria, six prism diopters of and by passing an FAA medical flight test (MFT). aviation/helicopter_flying_handbook/. Accessed September 28, 2017. the scan time. Effective scanning is accomplished with a patients. Regardless of vision correction to 20/20, cataracts esophoria, and six prism diopters of exophoria represent series of short, regularly-spaced eye movements that bring pose a significant risk to flight safety. FAA phoria (deviation of the eye) standards that may not be A Word about Contact Lenses successive areas of the sky into the central visual field. Each exceeded. -

Explore Your Blind Spot Discover How the Mind Hides Its

Explore your blind spot Discover how the mind hides its tracks by Tom Stafford Smashwords Edition (version 1.4, 2 July 2015) Copyright 2011 Tom Stafford This work is licensed under a Creative Commons Attribution-NonCommercial- ShareAlike 3.0 Unported License. Thank you for downloading this free eBook. You are welcome to share it with your friends. This book may be reproduced, copied and distributed for non-commercial purposes. You can even modify it, as long as the modified version is covered by the same licence. http://creativecommons.org/ Tom Stafford lives on the internet at http://idiolect.org.uk Follow him on twitter: @tomstafford Other ebooks by Tom: For argument’s sake: evidence that reason can change minds (2015) Control Your Dreams (2011) The Narrative Escape (2010) Your guide is Tom Stafford: This is a picture of the back of my eye, you can see the blood vessels and the optic disc, the light circle where they converge. It is this disc which produces the blind spots in our vision. You will need: pen, paper, eyes Your journey will take: minutes Category: perception Trig points: 3 The Treasure: Proud of your sharp sight? Perhaps you should think again. For each eye, there is a blind spot, an area near the middle of your vision for which you cannot see anything. Normally the way your vision works hides these blind spots from your awareness, but it isn't hard to show they're there. Visual blind spots are a good example of how our conscious experience is fundamentally based on our biological machinery. -

Afferent Visual Pathway Amr Hassan, M.D.,FEBN Associate Professor of Neurology Cairo University 2017

NOTE: To change the image on this slide, select the picture and delete it. Then click the Pictures icon in the placeholde r to insert your own image. Afferent visual pathway Amr Hassan, M.D.,FEBN Associate professor of Neurology Cairo University 2017 Agenda • Anatomy of visual pathway • Visual pathway disorders • Quiz 2 Agenda • Anatomy of visual pathway • Visual pathway disorders • Quiz 3 The Visual Pathway VISUAL FIELD Pathway extends from the „front‟ to the „back‟ of the RETINA brain. ON OC OT LGN OPTIC RADIATIONS ON = Optic Nerve OC = Optic Chiasm OT = Optic Tract LGN = Lateral Geniculate Nucleus of Thalamus VISUAL CORTEX 4 The Visual Pathway Eyes & Retina Light >> lens >> retina (inverted and reversed image). Eyes & Retina Eyes & Retina • Macula: oval region approximately 3-5 mm that surrounds the fovea, also has high visual acuity. • Fovea: central fixation point of each eye// region of the retina with highest visual acuity. Eyes & Retina • Optic disc: region where axons leaving the retina gather to form the Optic nerve. Eyes & Retina • Blind spot located 15° lateral and inferior to central fixation point of each eye. Object to be seen Peripheral Retina Central Retina (fovea in the macula lutea) 11 Photoreceptors © Stephen E. Palmer, 2002 Photoreceptors Cones • Cone-shaped • Less sensitive • Operate in high light • Color vision • Less numerous • Highly represented in the fovea >> have high spatial & temporal resolution >> they detect colors. © Stephen E. Palmer, 2002 Photoreceptors Rods • Rod-shaped • Highly sensitive • Operate at night • Gray-scale vision • More numerous than cons- 20:1, have poor spatial & temporal resolution of visual stimuli, do not detect colors >> vision in low level lighting conditions © Stephen E. -

Movement Phosphenes in Optic Neuritis

}. C!in. N~uro-ophthdlmol. 1: 279-282, 1981. Movement Phosphenes in Optic Neuritis MARC A. SWERDLOFF, B.A. ALlE ZIEKER, M.D. GREGORY B. KROHEL, M.D. bstnct improved over v roll w eks to 20/30. There was P~tients with optic neuriti m,J nole bright-colo~ a recurrent los of vi ion in the right e e in August fbshing lights upon enlry into ~ (Luk room, a.nd lhese 1978 with the visUAlI acuity at that time dropping movement phosphen m~ ~ ~ggnY~led b horizon to 20/200 in the ri ht eye. i ual acui in the nght bl eye mo ements. Thrft p~tienl.s wilh thi.s phenome e e returned to 20/ 0 in September 1978. In Feb non Me described. It m,J be.n irrit~tive symptom in ruary 1978, the patient hdd visual-evo ed poten the optic nerve ~alo ous to Lhermitte's sign in the tials, which reveal d a conduction deldy on the pinal cord. The differenlial di,Jgnos1S of "fbshing right side only. lights" i presented. The patient was seen in consultation on April 2, 1980. because f loss of visual acuity in the right eye associated with pain on e e movement. She had noted decreased vision in both eyes during In 1976, Davis et .11. noted an association be strenuous e ercise for the PdSt ear. isual dcuity tween e. e movement-induced positive visual phe was 20/70 in the right e e and 20/30 in the left nomena (movement phosphenes) and optic neuri eye. -

1 Laboratory #4: Human Visual System

SIMG-215-20061: LABORATORY #4 1 Laboratory #4: Human Visual System 1.1 Objective: To explore various aspects of the human visual system: specifically, location of the blind spot, lens accommodation, and dark adaptation. 1.2 Materials: 1. Your eyes 2. Your finger 3. Ruler 4. Pen 5. grayscale image (included on last page) 1.3 Background: The human eye is a roughly spherical, light-tight enclosure consisting of a hard, white outer wall called the sclera, a clear cornea that provided most of the optical power of the eye, the lens which can adjust its optical power to let you focus on objects at different distance, and a light sensitive layer at the rear of the eyeball called the retina where the image is formed. The retina includes two classes of receptors to detect light: rods and cones. The colored part of the eye is called the iris, which acts as a diaphragm to control the amount of light that enters the eye. The dark circular opening in the center of the iris is called the pupil. At the rear of the eyeball, along the retina but off axis from the center of the eye, is a bundle of nerve cells that carry the signals from the rods and cones to the brain for more processing and perception. The bundle of nerves is called the optic nerve and conveys the signals from the retina to the brain where they are processed for perception. Because of the layout of the eye, there are no light-sensitive cells at the location where the optic nerve leaves the eye, so you do not see that part of the image. -

Sensory Physiology

1 Human Physiology Lab (Biol 236L) Sensory Physiology External sensory information is processed by several types of sensory receptors in the body. These receptors respond to external stimuli, and that information is changed into an electrical signal (action potential) that is transmitted along the sensory division (afferent pathway) of the peripheral nervous system (PNS) to the central nervous system (CNS). This sensory signal initially occurs by activation of a sensory receptor. Receptor activation stimulates the opening or closing of ion-gated channels, which generates an action potential. The CNS, or integrating center, processes the information and then sends a response via motor division (efferent pathway) to effectors (muscle cells or glands) of the PNS for either a movement or secretory response, respectively. The sensory (afferent) division of the nervous system includes: 1) Somatic sensory division = transmission of sensory information from skin, fascia, joints, and skeletal muscles for balance and muscle movement to the CNS for interpretation. CNS will issue motor commands as needed to modify movements based on stimuli. The somatic sensory division can be involved in receiving sensory information that regulated involuntary and voluntary movement. In the skin there are several types of somatosensory receptors: mechanoreceptors, thermoreceptors, and nocireceptors. Mechanoreceptors are found in the skin, tongue, joints, and the bladder. They they detect pressure, vibration, and stretch. Thermoreceptors are found in the skin and hypothalamus; they can be divided into warm and cold receptors. Nocireceptors are found in the skin, cornea, visceral, joints, and skeletal muscles, and they are pain receptors that can be activated by mechanical, chemical, and even temperature extremes. -

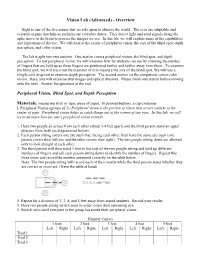

Vision Lab (Advanced) - Overview

Vision Lab (Advanced) - Overview Sight is one of the five senses that we rely upon to observe the world. The eyes are adaptable and versatile organs that help us perform our everyday duties. They detect light and send signals along the optic nerve to the brain to process the images we see. In this lab, we will explore some of the capabilities and limitations of the eye. We will look at the extent of peripheral vision, the size of the blind spot, depth perception, and color vision. The lab is split into two stations. One station covers peripheral vision, the blind spot, and depth perception. To test peripheral vision, we will examine how far students can see by counting the number of fingers that are held up as those fingers are positioned farther and farther away from them. To examine the blind spot, we will trace out the diameter of it to measure the size of the blind spot. We will use a simple coin drop test to examine depth perception. The second station (at the computers) covers color vision. Here, you will examine afterimages and optical illusions. Please finish one station before moving onto the next. Answer the questions at the end. Peripheral Vision, Blind Spot, and Depth Perception Materials: measuring stick or tape, piece of paper, 10 pennies/buttons, a cup/container I. Peripheral Vision (groups of 3): Peripheral vision is the portion of vision that occurs outside of the center of gaze. Peripheral vision helps us catch things out of the corner of our eyes. In this lab, we will try to measure how far one’s peripheral vision extends. -

Human Vision the Visual System

Human Vision The Visual System • The visual system consists of two parts. – The eyes act as image receptors. – The brain acts as an image processing and interpretation unit. • Understanding how we see requires that we understand both components. The Human Eye (The Right Eye Viewed From Above) Conjunctiva Zonula Retina Fovea Aqueous humour Lens Pupil Cornea Iris Optic nerve Constricted and Dilated Pupils Constricted Dilated Retinal Structure • Receptor cells are at the back of the retina. • Light passes “through the wiring”. • Horizontal cells do some initial signal processing. ganglion cell choroid horizontal cell rod bipolar cell cone Light Photo Receptor Cells • The eye contains two different classes of light sensitive cells (or photo receptors). • Rod cells provide sensitive low-light vision. • Cone cells provide normal vision. Rod Cells • Rod cells provide low-light vision. • There is only one type of rod cell. • Rod cells provide no colour discrimination. Cone Cells • Cone cells operate at medium and high light levels. • There are three different kinds of cone cells, each sensitive to different light wavelengths. • The sensitivity to different wavelengths is what provides us with colour vision. Rod And Cone Distribution • The distribution of rod and cone cells is not uniform across the retina. • The cones are concentrated at the centre rear of the retina and the rods are more evenly distributed away from that area. The Distribution of Rod and Cone Cells 200 Cones 150 Rods 100 50 Density in thousands per square mm 0 −80 −60 −40 −20 0 20 40 60 80 Angular distance from the fovea (in degrees) The Macula And Fovea • The centre-rear of the retina has a small yellow spot known as the macula.