Climate Change and Australia's Wildlife: Is Time Running Out?

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Local Population Structure of a Naturally Occurring Metapopulation of the Quokka (Setonix Brachyurus Macropodidae: Marsupialia)

Biological Conservation 110 (2003) 343–355 www.elsevier.com/locate/biocon Local population structure of a naturally occurring metapopulation of the quokka (Setonix brachyurus Macropodidae: Marsupialia) Matt W. Haywarda,b,c,*, Paul J. de Toresb,c, Michael J. Dillonc, Barry J. Foxa aSchool of Biological, Earth and Environmental Science, University of New South Wales, Sydney, NSW 2052, Australia bDepartment of Conservation and Land Management, Wildlife Research Centre, PO Box 51 Wanneroo, WA6946, Australia cDepartment of Conservation and Land Management, Dwellingup Research Centre, Banksiadale Road, Dwellingup, WA6213, Australia Received 8 May 2002; received in revised form 18 July 2002; accepted 22 July 2002 Abstract We investigated the population structure of the quokka (Setonix brachyurus) on the mainland of Western Australia using mark– recapture techniques. Seven previously known local populations and one unconfirmed site supporting the preferred, patchy and discrete, swampy habitat of the quokka were trapped. The quokka is now considered as locally extinct at three sites. The five remaining sites had extremely low numbers, ranging from 1 to 36 individuals. Population density at these sites ranged from 0.07 to 4.3 individuals per hectare. There has been no response to the on-going, 6 year fox control programme occurring in the region despite the quokkas’ high fecundity and this is due to low recruitment levels. The remaining quokka populations in the northern jarrah forest appear to be the terminal remnants of a collapsing metapopulation. # 2002 Elsevier Science Ltd. All rights reserved. Keywords: Population structure; Predation; Reproduction; Setonix brachyurus; Vulnerable 1. Introduction The Rottnest Island quokka population fluctuates around 5000 with peaks of 10,000 individuals (Waring, The quokka (Setonix brachyurus Quoy & Gaimard 1956). -

Post-Release Monitoring of Western Grey Kangaroos (Macropus Fuliginosus) Relocated from an Urban Development Site

animals Article Post-Release Monitoring of Western Grey Kangaroos (Macropus fuliginosus) Relocated from an Urban Development Site Mark Cowan 1,* , Mark Blythman 1, John Angus 1 and Lesley Gibson 2 1 Biodiversity and Conservation Science, Department of Biodiversity, Conservation and Attractions, Wildlife Research Centre, Woodvale, WA 6026, Australia; [email protected] (M.B.); [email protected] (J.A.) 2 Biodiversity and Conservation Science, Department of Biodiversity, Conservation and Attractions, Kensington, WA 6151, Australia; [email protected] * Correspondence: [email protected]; Tel.: +61-8-9405-5141 Received: 31 August 2020; Accepted: 5 October 2020; Published: 19 October 2020 Simple Summary: As a result of urban development, 122 western grey kangaroos (Macropus fuliginosus) were relocated from the outskirts of Perth, Western Australia, to a nearby forest. Tracking collars were fitted to 67 of the kangaroos to monitor survival rates and movement patterns over 12 months. Spotlighting and camera traps were used as a secondary monitoring technique particularly for those kangaroos without collars. The survival rate of kangaroos was poor, with an estimated 80% dying within the first month following relocation and only six collared kangaroos surviving for up to 12 months. This result implicates stress associated with the capture, handling, and transport of animals as the likely cause. The unexpected rapid rate of mortality emphasises the importance of minimising stress when undertaking animal relocations. Abstract: The expansion of urban areas and associated clearing of habitat can have severe consequences for native wildlife. One option for managing wildlife in these situations is to relocate them. -

Ba3444 MAMMAL BOOKLET FINAL.Indd

Intot Obliv i The disappearing native mammals of northern Australia Compiled by James Fitzsimons Sarah Legge Barry Traill John Woinarski Into Oblivion? The disappearing native mammals of northern Australia 1 SUMMARY Since European settlement, the deepest loss of Australian biodiversity has been the spate of extinctions of endemic mammals. Historically, these losses occurred mostly in inland and in temperate parts of the country, and largely between 1890 and 1950. A new wave of extinctions is now threatening Australian mammals, this time in northern Australia. Many mammal species are in sharp decline across the north, even in extensive natural areas managed primarily for conservation. The main evidence of this decline comes consistently from two contrasting sources: robust scientifi c monitoring programs and more broad-scale Indigenous knowledge. The main drivers of the mammal decline in northern Australia include inappropriate fi re regimes (too much fi re) and predation by feral cats. Cane Toads are also implicated, particularly to the recent catastrophic decline of the Northern Quoll. Furthermore, some impacts are due to vegetation changes associated with the pastoral industry. Disease could also be a factor, but to date there is little evidence for or against it. Based on current trends, many native mammals will become extinct in northern Australia in the next 10-20 years, and even the largest and most iconic national parks in northern Australia will lose native mammal species. This problem needs to be solved. The fi rst step towards a solution is to recognise the problem, and this publication seeks to alert the Australian community and decision makers to this urgent issue. -

Aussie Animals Aussie Reptiles Photos & Prese

S SSIE ANIMALS TION AU AUSSIE RE RESENTA PTILES PHOTOS & P KOALAS & PYTHONS QUOKKAS LIZARDS We are one of the few places in & KOALAS & CROCS Australia where you have the opportunity to HOLD a Koala for a The Quokka is a small macropod about the size of a domestic cat and it Australia is home to the world’s most amazing collection of lizards, great souvenir photo. For a small is found in Western Australia. Though they resemble rodents, Quokkas dragons and monitors. Camouflage is their key to survival, so take additional cost, you will have a are actually marsupials, like kangaroos and wallabies. your time and try to find them. memory to last a lifetime. Or for Everyone one loves a Koala! Whether they are eating, sleeping or just Crocodiles have been part of the Australian eco- something on the “scaly side”, have a looking adorable, they are Australia’s most loved animal. Over millions system for millions of years. Here you will find photo with a large python. (extra cost) of years, the Koala’s diet has evolved to one that is exclusively of Freshwater Crocodiles which are mainly found eucalyptus leaves. in inland river systems. The larger and more aggressive Saltwater or Estuarine Crocodile NOCTURNAL WALLABIES & WOMBATS found in coastal river systems, can be seen at Hartley’s Crocodile Adventures. WONDERS TOUR Did you know that Australia has over 70 2.00pm Join our Wildlife Keeper for species of macropods, ranging from the a short guided walk through the new tiny Musky Rat Kangaroo to the giant Red PIONEERING HISTORY Nocturnal Wonders exhibit learning Kangaroos seen in the Outback? Meet, pat Kuranda Koala Gardens is operated about Bilbies, possums and gliders. -

Knowing Is Half the Battle

FALL 2018/WINTER 2019 NEWSLETTER 4600 N. Fairfax Dr. 7th Floor Arlington, VA 22203 We Protect Species Adirondack Mountains | Photo by Kenable2 Bald Eagle (Haliaeetus leucocephalus), NatureServe Global Status: Secure (G5), Range: North America Knowing Is Population Data Source: USFWS Figure shows number of breeding pairs Half the Battle Protecting populations of plants and animals while they are healthy is preferable to Effective conservation always begins with sound information. What desperate, last-ditch efforts to rescue species James Brumm species and habitats are there? Where do they occur? How are they from the brink of extinction. Unfortunately Chair doing and what can we do about it? NatureServe is the authoritative many species are already in dire trouble—for source of comprehensive biodiversity data and analyses that can these species we need the Endangered Species Board of answer these questions. I’m proud to support NatureServe because Pairs Breeding Act (ESA). Without the ESA, many iconic animals our information empowers better stewardship of our shared lands and and plants would likely have disappeared Directors waters. forever from America’s natural landscape. As the newly appointed Chair of the Board of Directors, I’m thrilled Did you know that NatureServe data is critical to begin my tenure alongside NatureServe’s President & CEO, Sean to protecting species through the Endangered T. O’Brien, Ph.D. His passion for conserving the Earth’s vast variety of Species Act? NatureServe data provide plants, animals, and ecosystems is evident, and he has already made objective and unbiased scientific assessments great strides for NatureServe. I’m confident that he will continue of a species’ risk of extinction. -

Recovery Plan for the Bramble Cay Melomys Melomys Rubicola Prepared by Peter Latch

Recovery Plan for the Bramble Cay Melomys Melomys rubicola Prepared by Peter Latch Title: Recovery Plan for the Bramble Cay Melomys Melomys rubicola Prepared by: Peter Latch © The State of Queensland, Environmental Protection Agency, 2008 Copyright protects this publication. Except for purposes permitted by the Copyright Act, reproduction by whatever means is prohibited without the prior written knowledge of the Environmental Protection Agency. Inquiries should be addressed to PO Box 15155, CITY EAST QLD 4002. Copies may be obtained from the: Executive Director Conservation Services Environmental Protection Agency PO Box 15155 CITY EAST Qld 4002 Disclaimer: The Australian Government, in partnership with the Environmental Protection Agency facilitates the publication of recovery plans to detail the actions needed for the conservation of threatened native wildlife. The attainment of objectives and the provision of funds may be subject to budgetary and other constraints affecting the parties involved, and may also be constrained by the need to address other conservation priorities. Approved recovery actions may be subject to modification due to changes in knowledge and changes in conservation status. Publication reference: Latch, P. 2008.Recovery Plan for the Bramble Cay Melomys Melomys rubicola. Report to Department of the Environment, Water, Heritage and the Arts, Canberra. Environmental Protection Agency, Brisbane. 2 Contents Page No. Executive Summary 4 1. General information 5 Conservation status 5 International obligations 5 Affected interests 5 Consultation with Indigenous people 5 Benefits to other species or communities 5 Social and economic impacts 5 2. Biological information 5 Species description 5 Life history and ecology 7 Description of habitat 7 Distribution and habitat critical to the survival of the species 9 3. -

Long-Nosed Potoroo (Potorous Tridactylus)

Action Statement No. 254 Long-nosed Potoroo Potorous tridactylus Flora and Fauna Guarantee Act 1988 Authorised and published by the Victorian Government, Department of Environment and Primary Industries, 8 Nicholson Street, East Melbourne, December 2013 © The State of Victoria Department of Environment and Primary Industries 2013 This publication is copyright. No part may be reproduced by any process except in accordance with the provisions of the Copyright Act 1968. Print managed by Finsbury Green December 2013 ISBN 978-1-74287-975-8 (Print) ISBN 978-1-74287-976-5 (pdf) Accessibility If you would like to receive this publication in an alternative format, please telephone DEPI Customer Service Centre 136186, email [email protected], via the National Relay Service on 133 677 www.relayservice.com.au This document is also available on the internet at www.depi.vic.gov.au Disclaimer This publication may be of assistance to you but the State of Victoria and its employees do not guarantee that the publication is without flaw of any kind or is wholly appropriate for your particular purposes and therefore disclaims all liability for any error, loss or other consequence which may arise from you relying on any information in this publication. Cover photo: Long-nosed Potoroo at Healesville Sanctuary (Peter Menkhorst) Action Statement No. 254 Long-nosed Potoroo Potorous tridactylus Description On the Australian mainland the Long-nosed Potoroo has a patchy distribution along the eastern and south- The Long-nosed Potoroo (Potorous tridactylus) (Kerr eastern seaboard from around Gladstone in south-eastern 1972) is one of the smallest members of the kangaroo Queensland to Mt Gambier in the south-eastern corner of superfamily (the Macropodoidea) and one of 10 species South Australia (van Dyck and Strahan 2008). -

Scarlett Fox, with Help from Hannah Schardt Dear Rick, G’Day from Topsy-Turvy Australia! It Might Be Late Fall Back Home, but Down Here It’S Almost Summer

by Scarlett Fox, with help from Hannah Schardt Dear Rick, G’day from topsy-turvy Australia! It might be late fall back home, but down here it’s almost summer. (Australia is in the Southern Hemisphere, so seasons here are the opposite of ours in the United States.) Seasons aren’t the only things that are different Down Under. I’ve never met so many strange animals in my life. There are mammals that lay eggs! Birds that are taller than humans! And it seems that everywhere I turn, there’s an animal with a dangerous bite. Naturally, I LOVE it here! Can’t wait to show you all the photos I’ve taken of my new Aussie friends. More later—time to head back to the Outback! (That’s the dry, wild ASIA NORTHERN middle of the country.) HEMISPHERE EQUATOR Wish you were here, Scarlett AUSTRALIA SOUTHERN HEMISPHERE ANTARCTICA black-headed python eastern water dragon sugar glider emu quokka dingo ALL PHOTOS FROM MINDEN PICTURES, PAGES 6–13: JÜRGEN FREUND/NPL (6L) >; BROOK WHATNALL/NGCREATIVE 6 (6M); THOMAS MARENT (6R); ROB DRUMMOND/BIA (7L); KEVIN SCHAFER (7M) >; MARTIN WILLIS (7R) 7 TO : G’Day, Zelda! Australia is full of your cousins— Zelda Possum marsupials! As you know, marsupials The cat-sized spotted- 101 Oak Tree Lane tailed quoll is the largest (mar-SOO-pee-ulz) give birth to tiny, Deep Green Wood, USA meat-eating marsupial helpless babies. Most have pouches for in mainland Australia. carrying their babies until they are old (The Tasmanian devil is enough to follow Mom around. -

Behaviour, Group Dynamics, and Health of Free-Ranging Eastern Grey Kangaroos

Behaviour, group dynamics, and health of free-ranging eastern grey kangaroos (Macropus giganteus) Jai Mikaela Green-Barber Submitted for the completion of a Doctor of Philosophy (Science) degree at Western Sydney University November 2017 Dedication The following thesis is dedicated to my hero. You instilled in me an appreciation of nature and of knowledge, you showed me the joys of solving puzzles and debating ideas, and you always encouraged me to be daring when the reward was worth the risk. Most importantly you always taught me to laugh along the way, to laugh at myself, and not take life too seriously. These gifts you have given me have led me down this path, and gave me the strength to complete the journey. Your influence will continue to shape the rest of my life. This one’s for you Dad xoxo Acknowledgements I would like to thank Associate Professor Julie Old for the encouragement and support needed to complete this thesis. I really appreciate you putting up with my essay length emails full of questions and all the feedback on the countless draft manuscripts and presentations produced throughout my candidature. To Dr Hayley Stannard, thank you for teaching me to collect blood samples and run blood chemistry analysis, and for the helpful feedback on draft manuscripts. Thank you to Dr Oselyne Ong for teaching me how to run antimicrobial assays, Megan Callander for teaching me how to use various microsatellite analysis software, and Professor John Hunt for providing feedback on draft manuscripts and advice on analysis. To all the volunteers that assisted me in the field your help was greatly appreciated. -

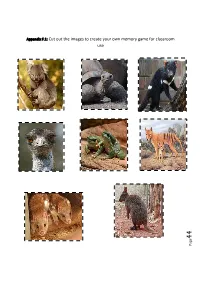

Appendix F.1: Cut out the Images to Create Your Own Memory Game for Classroom Use

Appendix F.1: Cut out the images to create your own memory game for classroom use 44 44 Page 45 45 Page Appendix F.2: REPTILES o Colour and then cut out each picture o Make each reptile a suitable habitat and paste them into their new home 46 46 Page Appendix F.3 Draw your favorite part of the trip to the Ballarat Wildlife Park 47 Page Appendix F.4 Map of the Ballarat Wildlife Park 48 48 Page Appendix F.5 Role Play Animals: o Kangaroo o Lizard o Koala o Snake o Crocodile o Emu o Turtle o Wombat o Tasmanian devil o Eagle 49 Page Appendix 1.1 50 50 Page Appendix 1.2 ‘SIMON SAYS’ EXAMPLES Teacher notes Simon says hop like a kangaroo/ hop like a kangaroo Simon says snap like a crocodile/ snap like a crocodile Simon says climb a tree like a koala/ climb a tree like a koala Simon says eat gum leaves like a koala/ eat gum leaves like a koala Simon says slither like a snake/ slither like a snake Simon says jump like a frog/ jump like a frog Simon says flap your wings like a bird/ flap your wings like a bird Simon says point your tongue out like a blue tongue lizard/ point your tongue out like a blue tongue lizard Extension… Simon says hop twice/ hop twice Simon says snap like a crocodile and wiggle your tail/ snap like a crocodile and wiggle your tail. Simon says jump like a frog twice, jump like a frog twice Simon says jump like a frog and then flap your wings like a bird/ jump like a frog and flap your wings 51 Page Appendix 2.1 Image can be re-sized on photocopier or you can choose your own 52 52 Page Appendix 2.2 ANIMAL NAME OF -

1.4.1. Habitat Use by the Long-Nosed Potoroo 32

University of Wollongong Thesis Collections University of Wollongong Thesis Collection University of Wollongong Year Habitat associations of the long-nosed potoroo (potoroos tridactylus) at multiple spatial scales Melinda A. Norton University of Wollongong Norton, Melinda A, Habitat associations of the long-nosed potoroo (potoroos tridactylus) at multiple spatial scales, MSc thesis, School of Biological Sciences, University of Wollongong, 2009. http://ro.uow.edu.au/theses/832 This paper is posted at Research Online. http://ro.uow.edu.au/theses/832 HABITAT ASSOCIATIONS OF THE LONG-NOSED POTOROO (Potoroos tridactylus) AT MULTIPLE SPATIAL SCALES Melinda A. Norton BSc. (Hons) UNSW A thesis submitted in fulfilment of the requirements for the degree of Master of Science (Research) School of Biological Sciences, University of Wollongong March 2009 CERTIFICATE OF ORIGINALITY I, Melinda A. Norton, declare that this thesis, submitted in accordance with the regulations of the University of Wollongong in fulfilment of the requirements for the degree Master of Science (Research). The work in this thesis is wholly my own unless otherwise references or acknowledged. The document has not been submitted for qualifications at any other academic institution. Melinda Ann Norton 31 March 2009 ABSTRACT The long-nosed potoroo (Potorous tridactylus) is a threatened, ground-dwelling marsupial known to have been highly disadvantaged by changes brought about since European settlement in Australia. Key threats to the species are believed to be fox predation and habitat loss and/or fragmentation. In order to conserve the species, the important habitat elements for the species at both the coarse and fine scale need to be identified and managed appropriately. -

Potorous Tridactylus) at Multiple Spatial Scales

University of Wollongong Research Online Faculty of Science - Papers (Archive) Faculty of Science, Medicine and Health January 2010 Habitat associations of the long-nosed potoroo (Potorous tridactylus) at multiple spatial scales Melinda A. Norton [email protected] Kristine O. French University of Wollongong, [email protected] Andrew W. Claridge University of NSW Follow this and additional works at: https://ro.uow.edu.au/scipapers Part of the Life Sciences Commons, Physical Sciences and Mathematics Commons, and the Social and Behavioral Sciences Commons Recommended Citation Norton, Melinda A.; French, Kristine O.; and Claridge, Andrew W.: Habitat associations of the long-nosed potoroo (Potorous tridactylus) at multiple spatial scales 2010, 303-316. https://ro.uow.edu.au/scipapers/683 Research Online is the open access institutional repository for the University of Wollongong. For further information contact the UOW Library: [email protected] Habitat associations of the long-nosed potoroo (Potorous tridactylus) at multiple spatial scales Abstract This study examined the coarse- and fine-scale habitat preferences of the long-nosed potoroo (Potorous tridactylus) in the Southern Highlands of New South Wales, in order to inform the management of this threatened species. Live-trapping was conducted in autumn and spring, from 2005 to 2008, at two sites. Macrohabitat preferences were examined by comparing trap success with numerous habitat attributes at each trap site. In spring 2007 and autumn 2008, microhabitat use was also examined, using the spool- and-line technique and forage digging assessments. While potoroos were trapped in a wide range of macrohabitats, they displayed some preference for greater canopy and shrub cover, and ground cover with lower floristic diversity.