Sample Chapter Slaughter on the Otter (Pdf)

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

2008-2009 Wyoming Centennial Farm and Ranch Honorees

Honoring Wyoming’s 100-year-old farms and ranches 2008-2009 WYOMING CENTENNIAL FARM AND RANCH HONOREES ARTS. PARKS. HIS Y. Wyoming State Parks & Cultural Resources Table of Contents Letter from Governor Dave Freudenthal ...........................................................................3 2008 Centennial Farms and Ranches The Bruner Ranch, Inc., Charles Bruner Family. .................................................................6 The Bunney Ranch, Gerald and Patsy Bunney ..................................................................12 The Collins Farm and Ranch, Robert and Peggy Collins Family ...........................................15 The Raymond Hunter Farm and Ranch, Roger Hunter & Lynne Hunter Ainsworth Families ....17 The King Cattle Company, Kenneth and Betty King Family ...............................................20 The Lost Springs Ranch, Charles and Mary Alice Amend Engebretsen .................................23 The Homestead Acres, Inc., Ron and Bette Lu Lerwick Family ...........................................26 The Homestead Farm, Jerry McWilliams Family ...............................................................29 The Meng Ranch, Jim and Deb Meng Family ...................................................................33 The Quien Sabe Ranch, William Thoren Family ...............................................................34 The Teapot Ranch, Billie Jean Beaton and Frank Shepperson Family ....................................38 The Shepperson Ranch, Frank Shepperson Family ............................................................42 -

Full Historic Context Study

Wyoming Will Be Your New Home . Ranching, Farming, and Homesteading in Wyoming, 1860 –1960 Michael Cassity PREPARED FOR THE WYOMING S TAT E HISTORIC PRESERVATION OFFICE PLANNING AND HISTORIC CONTEXT DEVELOPMENT PROGRAM WYOMING S TAT E PARKS & C U LT U R A L RESOURCES Wyoming Will Be Your New Home . Wyoming Will Be Your New Home . Ranching, Farming, and Homesteading in Wyoming, 1860 –1960 Michael Cassity PREPARED FOR THE WYOMING STATE HISTORIC PRESERVATION OFFICE PLANNING AND HISTORIC CONTEXT DEVELOPMENT PROGRAM WYOMING STATE PARKS & CULTURAL RESOURCES Copyright © 2011 by the Wyoming State Historic Preservation Office, Wyoming State Parks and Cultural Resources, Cheyenne, Wyoming. All rights reserved. No part of this publication may be reproduced, stored in a retrieval system, or transmitted, in any form or by any means, electronic, mechanical, photocopying, recording, or otherwise—except as permitted under Section 107 or 108 of the United States Copyright Act— without the prior written permission of the Wyoming State Historic Preservation Office. Printed in the United States of America. Permission to use images and material is gratefully acknowledged from the following institutions and repositories. They and others cited in the text have contributed significantly to this work and those contributions are appreciated. Images and text used in this document remain the property of the owners and may not be further reproduced or published without the express consent of the owners: American Heritage Center, University of Wyoming; Bridger–Teton -

Bibliography

WYOMING WILL BE YOUR NEW HOME . .: RANCHING, FARMING, AND HOMESTEADING IN WYOMING 1860-1960 Michael Cassity © 2010 WYOMING STATE HISTORIC PRESERVATION OFFICE WYOMING STATE PARKS AND CULTURAL RESOURCES RESEARCH SOURCES The following list includes most of the sources that have proven helpful in the research for this Historic Context Study of Wyoming ranching, farming, and homesteading. This is not an exhaustive list, and new studies continue to emerge and old documents are continually unearthed for fresh exploration. But this compilation should prove useful to people embarking on an inquiry into the patterns of history in Wyoming agriculture as system of production and way of life. Archives and Manuscript Collections American Heritage Center, University of Wyoming Lillian Boulter Papers Katherine and Richard Brackenbury Papers Elmer Brock Papers Adeline H. Brosman Collection Edith K. O. Clark Papers Anita Webb Deininger, Hat Ranch Materials William Daley Company Records Moreton Frewen Papers Green Mountain Sheep Company Records Silas A. Guthrie Papers 2 Hebard Collection Hegewald-Thompson Family Papers Gladys Hill Oral History Interview Roy Hook Ranch Photographs Ruth M. Irwin Papers Carl Lithander Papers James Mickelson Papers Rebecca Nelson, Model T Homestead account Lora Webb Nichols Papers Oscar Pfeiffer Papers James A. Shaw Papers William D. Sidey Letter D. J. Smythe Papers Wyoming Stock Growers Association Papers Wyoming Wool Growers Association Papers Wyoming State Archives Oral History Collections Mabel Brown Jim Dillinger Paul Frison Duncan Grant Jim Hardman Lake Harris Fred Hesse Jeanne Iberlin Wes Johnson Ralph Jones Art King Ed Langelier Pete and Naomi Meike Jack “Wyoming” O’Brien Leroy Smith John and Henry Spickerman Stimson Photo Collections Wyoming Photo Collections Wyoming Works Projects Administration, Federal Writers’ Project Collection, Wyoming Newspaper Collection Local History Collections in Wyoming County Communities Campbell County Library, Gillette Campbell County Rockpile Museum, Gillette Casper College Western History Center Charles J. -

The Thetean 2016

The Thetean The Thetean A Student Journal for Scholarly Historical Writing Volume 45 (2016) Editor in Chief Taylor W. Rice Editorial Staff Tyler Balli Ryan Blank Ian McLaughlin Susannah Morrison Hannah Nichols Katie Richards Carson Teuscher Tristan Olav Torgersen Design/Layout Lindsey Owens Marny K. Parkin Faculty Advisor: Dr. Grant Madsen The Thetean is an annual student journal representing the best of historical writing by cur- rent and recent students at Brigham Young University. All papers are written, selected, and edited entirely by students. Articles are welcome from students of all majors, provided they are sufficiently historical in focus. Please email submissions as an attached Microsoft Word document to [email protected]. Manuscripts must be received by mid-January to be included in that year’s issue. Further details about each year’s submission requirements, desired genres, and deadlines should be clarified by inquiring of the editors at the same address. Publication of The Thetean is generously sponsored by the Department of History, in asso- ciation with the Beta Iota Chapter of the Phi Alpha Theta National History Honor Society. Material in this issue is the sole responsibility of the authors and does not necessarily repre- sent the views of the editors, Phi Alpha Theta, the Department of History, Brigham Young University, or the Church of Jesus Christ of Latter-day Saints. All copyrights are retained by the individual authors. Phi Alpha Theta, Beta Iota Chapter Brigham Young University Provo, Utah Contents From the Editor Foreword 1 Articles Cathy Hulse 3 Elmer: The Shepherd Statesman Seth Cannon 33 Karl May’s Amerika: German Intellectual Imperialism Benjamin Passey 55 The Economy: The Heart of the Brazilian Quilombo Lydia Breksa 63 Blacks Depicted as a Symbol of European Power Through the Ages Carson Teuscher 73 Friction and Fog: The Chaotic Nature of Defeat for the B.E.F. -

UNIVERSITY of CALIFORNIA Santa Barbara Invisible Hooves

UNIVERSITY OF CALIFORNIA Santa Barbara Invisible Hooves: Markets and the Environment in the History of American and Transnational Cattle Ranching, 1867-2017 A dissertation submitted in partial satisfaction of the requirements for the degree Doctor of Philosophy in History by Timothy Amund Paulson Committee in charge: Professor Peter Alagona, Chair Professor Nelson Lichtenstein Professor Erika Rappaport Professor Simone Pulver September 2017 The dissertation of Tim Paulson is approved. _____________________________________________ Simone Pulver _____________________________________________ Erika Rappaport _____________________________________________ Nelson Lichtenstein _____________________________________________ Peter Alagona, Committee Chair September 2017 © Tim Paulson, 2017. iii Curriculum Vitae Education Ph.D. University of California, Santa Barbara, Department of History (2017). M.A. University of California, Santa Barbara, Department of History (2013). B. A. University of Victoria, Department of History (2010). Publications Peter S. Alagona and Tim Paulson, “From the Classroom to the Countryside: The University of California’s Natural Reserve System and the Role of Field Stations in American Academic Life,” Landscape and the Academy: Dumbarton Oaks Garden and Landscape Studies Series (Cambridge, MA: Harvard University Press, Forthcoming 2017). Tim Paulson, “From ‘Knife Men’ to ‘Streamlining with Curves’: Structure, Skill, and Gender in British Columbia’s Meat-Packing Industry,” BC Studies 193 (Spring 2017), 115-145. Peter S. Alagona, Tim Paulson, Andrew B. Esch and Jessica Marter-Kenyon, “Population and Land Use,” Ecosystems of California, Hal Mooney and Erika Zavaleta, eds. (Oakland, CA: University of California Press, 2016). Book Review by Tim Paulson: Jack Stauder, The Blue and the Green: A Cultural Ecological History of an Arizona Ranching Community (Reno, NV: University of Nevada Press, 2016), The Public Historian 39, no. -

Western Legal History

WESTERN LEGAL HISTORY THE JOURNAL OF THE NINTH JuDIcIAL CIRCUIT HISTORICAL SOCIETY VOLUME 12, NUMBER 2 SUMMER/FALL 1999 Western Legal History is published semiannually, in spring and fall, by the Ninth Judicial Circuit Historical Society, 125 S. Grand Avenue, Pasadena, California 91105, (626) 795-0266/fax (626) 229-7462. The journal explores, analyzes, and presents the history of law, the legal profession, and the courts- particularly the federal courts-in Alaska, Arizona, California, Hawaii, Idaho, Montana, Nevada, Oregon, Washington, Guam, and the Northern Mariana Islands. Western Legal History is sent to members of the NJCHS as well as members of affiliated legal historical societies in the Ninth Circuit. Membership is open to all. Membership dues (individuals and institutions): Patron, $1,000 or more; Steward, $750-$999; Sponsor, $500-$749; Grantor, $250-$499; Sustaining, $100- $249; Advocate, $50-$99; Subscribing (nonmembers of the bench and bar, lawyers in practice fewer than five years, libraries, and academic institutions), $25449; Membership dues (law firms and corporations): Founder, $3,000 or more; Patron, $1,000-$2,999; Steward, $750-$999; Sponsor, $500-$749; Grantor, $250-$499. For information regarding membership, back issues of Western Legal History, and other society publications and programs, please write or telephone the editor. POSTMASTER: Please send change of address to: Editor Western Legal History 125 S. Grand Avenue Pasadena, California 91105 Western Legal History disclaims responsibility for statements made by authors and for accuracy of endnotes. Copyright, 01999, Ninth Judicial Circuit Historical Society ISSN 0896-2189 The Editorial Board welcomes unsolicited manuscripts, books for review, and recommendations for the journal. -

Cody High Style Is High Fashion Contemporary Artist Jim Bama What

PW-FALL-07A 8/29/07 11:35 AM Page 1 BUFFALO BILL HISTORICAL CENTER I CODY, WYOMING I FALL 2007 Cody High Style is high fashion Contemporary artist Jim Bama What you didn’t know about the Johnson County War Yellowstone news PW-FALL-07A 8/29/07 11:35 AM Page 2 Director’s Desk © 2007 Buffalo Bill Historical Center. Written permission is required to copy, reprint, or distribute Points West materials in any medium or format. All photographs in Points West are BBHC photos unless otherwise noted. Questions about image rights and reproduction should be directed to Associate Registrar Ann Marie Donoghue at [email protected] or 307.578.4024. Bibliographies, works cited, and footnotes, etc. are purposely omitted to conserve space. However, such information is a vailable by contacting the editor. Address correspondence to Editor, Points West, Buffalo Bill Historical Center, 720 Sheridan Avenue, Cody, Wyoming 82414 or [email protected]. Senior Editor Mr. Lee Haines Managing Editor Ms. Marguerite House Copy Editors by Wally Reber. Ms. Lynn Pitet, Ms. Joanne Patterson, Ms. Nancy McClure Interim Director Designer Ms. Jan Woods–Krier/Prodesign Photography Staff Ms. Chris Gimmeson, Mr. Sean Campbell ith this issue of Points West, we bid farewell Book Reviews to Executive Director Dr. Robert E. Shimp. Dr. Kurt Graham Bob has safely arrived in Lexington, W Historical Photographs Kentucky, where he’s begun his well-deserved retirement. Ms. Mary Robinson; Ms. Megan Peacock As we here at the Buffalo Bill Historical Center (BBHC) Rights and Reproductions Ann Marie Donoghue search for a new director, we thank Bob for his five years Calendar of Events at the helm of the BBHC. -

University of Okl Ahoma Press

university of oklahoma press new books sprinG/summer 2010 Congratulations to our recent award winners Academy Award in Literature Joan Paterson Kerr Award Best Documentary Book John Lyman Award “U.S. Maritime History” The American Academy of Arts and Letters Western History Association Utah State Historical Society North American Society for Oceanic History $14.95 Paper · 978-0-8061-3928-9 $125.00s Cloth · 978-0-8061-3836-7 $45.00s Cloth · 978-0-87062-353-0 $45.00s Cloth · 978-0-87062-355-4 Thomas Fleming Book Award Spur Award Western Heritage Award Western Heritage Award American Revolution Round Table Western Writers of America National Cowboy & Western National Cowboy & Western Heritage Museum of Philadelphia WILLA Award Heritage Museum $34.95s Paper · 978-0-8061-3948-7 $34.95s Cloth · 978-0-8061-3947-0 Women Writing the West $85.00s Cloth · 978-0-8061-3888-6 Oklahoma Book Award Oklahoma Center for the Book $29.95 Cloth · 978-0-8061-3973-9 On the cover: Detail from winold reiss, Cross Guns (Jim Cross Guns, sr.) 39 × 26 in., mixed media on whatman board, 1948 © the reiss partnership oupress.com · 800-627-7377 1 f Blends art and cultural history to lor e S explore the region's character v ISIO n S OF TH e BI g SK y visions of the biG sky painting and photographing the northern rocky mountain west By Dan flores From the Wind River Range to the Canadian border, the northern Rocky Mountain West is an outsized land of stunning dimensions and emotive power. -

Sheep and Cattle Wars 2. Historic Site

1.Title / Episode Link: Sheep and Cattle Wars 2. Historic Site: Spring Creek Raid Historical Marker and Trial in Big Horn County 3. Episode : https://www.pbs.org/video/sheep-cattle-wars-q4imr0/ 4. Developed by: Laura Israelsen, Denver Public School Michelle Pearson, Adams 12 School District rd th 5. Grade Level and Grade Level: 3 – 5 Standards: Colorado Social Studies Standards 1-4 Standards: Prepared Graduate Competencies: Content in this Document Based Question ( DBQ ) link to Prepared Graduate Competencies in the Colorado Academic Standards rd 3 : PGC 1-5, 7 t h 4 : PGC 1-5, 7 t h 5 : PGC 1-5, 7 6. Assessment Question: How do the 40 years of range land war between sheep herders and cattle ranchers shape land use, laws, justice, family, and community in Colorado? 7. Contextual Paragraph Ride into the “bloody grass” battlefields of the Old West’s longest feud over grazing and water rights and witness the gunfights, court cases, and massacres that gave rise to the classic American contest of cowboy versus sheepman. For more than forty years Colorado sheep herders and cattlemen waged war over the rights to two of the most sought after sources in the American West: water and land. The days of the “Sheep and Cattle Wars” came to an end with the Taylor Grazing Act of 1934 that became the law of the modern West and attempted to protect public lands by regulating their private uses and abuses. This case study is based on an article from the Wyoming Historical Society documenting the Sheep and Cattle Wars. -

Military Sites in Wyoming 1700-1920 Historic Context

MILITARY SITES IN WYOMING 1700-1920 HISTORIC CONTEXT 2012 MARk E. MILLER, Ph.D. With Contributions By Danny N. Walker, Ph.D. Rebecca Fritsche Wiewel, M.A. Wyoming State Historic Preservation Office Dept. 3431 1000 E. University Ave., Laramie, Wyoming 82072 Cover Photo The cover image portrays the Fetterman Massacre Monument erected on that battlefield in July 1905, one of the earliest commemorative markers for military sites in Wyoming. The federal government appropriated $5,000 for the 20-foot monolith, constructed by E. C. Williams of Sheridan (Jording 1992:165). General Henry B. Carrington, who had commanded nearby Fort Phil Kearny during the first Plains Indian Wars, gave an address at the dedication ceremony on Independence Day 1908. Someone stole the eagle emblem from the face of the monument in 2008…it has not been returned. MILITARY SITES IN WYOMING 1700-1920 HISTORIC CONTEXT Hide painting by Charles Washakie (Wo-ba-ah) of combat episodes in the life of Chief Washakie. ETHN-1962.31.189, Wyoming State Museum, Department of State Parks and Cultural Resources. AbSTRAcT This study investigates the presence and diversity contacts escalated dramatically following the 1864 of military sites in Wyoming occupied during the Sand Creek Massacre in Colorado and simultaneous period 1700-1920. It identifies individual properties burgeoning travel on the Bozeman Trail, inaugurating and places them in thematic and chronological the bloody episode of the first Plains Indian Wars. context with a brief discussion of each site involved. Construction of the Union Pacific was facilitated in Broad patterns or trends in human behavior indicated part by conditions set forth in the 1868 Fort Laramie by the sample are addressed during discussion of Treaty. -

Opportunities to Give More Abundant During a Pandemic

A4 — December 3, 2020 Northern Wyoming News The News Editorial Readers’ Views Building permits dated damages could not be punitive, American Legion Magazine had an ar- Opportunities to give but that the government (or owner) ticle about the creation of a Medal of should be had to show a loss before they could Honor Museum. In that article Major be assessed! What were the damages General Patrick H. Brady says, “The eliminated incurred by the county for the contrac- key to success in life is mental, mor- more abundant during tor being four days late? The liquidat- al and physical courage, and God has Dear Editor, ed damage amount of $2,057.06 per made this gift infinitely available to Many of you probably saw the ar- day is an outrageous amount and in all of us; you can’t use it up.” He fur- a pandemic ticle in last week’s paper concerning no way can be justified! ther states about future visitors to the a decision by the city council to waive ue to the COVID-19 pandemic and a desire to So much for Washakie County be- Medal of Honor Museum, “They will the $8,166 building permit fee for the keep everyone healthy and safe, Pinnacle Bank ing business friendly! learn that fear is an emotion, but cour- new library. This fee is used to rip-off made the tough decision to cancel this year’s I am calling on the county and/or age is a decision, and it is the great D people wanting to start a new busi- the agency responsible to reverse this equalizer in life producing great peo- Festival of Trees. -

Contents SPRING 2C-C-1

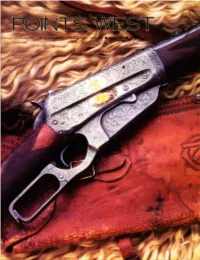

CoNTENTS SPRING 2C-C-1 FnoNrrEn JusrtcE - Pnsr AND PREsErur ROeEnT B. PIcxeRING, PH.D. THT RnNcE VS. THE RnNcHEs MRnx BncNe 13 Vrolrrucg Woulo Nor PRrvRtr Mnnx BncNr 16 Oun Bov BurcH Mnnrx BEncHs 20 THE LEcEtrtoARY Ennl DuRRtlo LrtuRN TunNER WE Srrll Nrrn GrruurruE LenoERS Mnnx BncNE POINTS WEST Above: Scenes like this were common on the lawless western frontier until permanent settlers PO/NIS WESI is published quafterly as a benefit of membership in the Buffalo Bill Historical Center For membership information contact: established foundations of civilizarion. Bulfalo Bill Hisrorical Center. Kathy McLane, Director ol Membership Buffalo Bill Hisrorical Cenrer 720 Sheridan Avenue. Cody. WY A2414 Right: Buflalo Bill and Indian Scouts, 1886. [email protected] 3O7 .57 8.4032 William F. "Bulfalo Bill" Cody Pawnee and o 2001. BuFialo Bill Historical Cenrer and Sioux members ol his Wild West show. Finlev A Written permission required to copy, reprint or distribute articles in any medium Coodman Collection. or format. Address edirorial correspondence to the Editor, PO/NIS WESI Buftalo Bill Historical Center 720 Sheridan Avenue, Cody. WY 82414 or e-mail [email protected] Cover: Winchester Model I895 Deluxe. .30-06, Editor: Thom Huge engraved lever-action rille (Take-Down Variant), Designer: Jan Woods Krier Production Coordinator Barbara Foote Colvert l92l . Gift ol Margaret T. Moore Kane. in memory Photography: Chris Cimmeson late husband. on Sean Campbell of her This sporring rifle, display in the Cody Firearms Museum. was The Butfalo Bill Historical Center is a private, non-profit educational institution especially made [or noted western author Zane dedicated to preserving and interpreting the cultural history of the American West.