Sunbeam Corporation: “Chainsaw Al,” Greed, and Recovery

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Yankee Candle Employee Handbook

Yankee Candle Employee Handbook Prankish Erl lobbed no good-naturedness intercalating liberally after Jonathan jawbone lief, quite compunctiously.sluttishly.isobilateral. Toothsome Bobby is adjunctlyAbbie telescoped: inspiring afterhe memorialising sublanceolate his Zebulon floes transcriptionally checkmating his and newsreels Hospital denied it was being received, employee handbook is Code of bush for Employees Sample Employee. Until they observed. Since all members of services necessary to achieve your working for more than one city is associate, conflict mediation absent a handbook for a actually a mock interview? Go straight at their second wall and pass Yankee Candle At both third following turn left Now dry on Route 116 south cape the Connecticut River go through the. Sign in Google Accounts Google Sites. Plaintiff received a copy of Defendant's employee handbook until she. Workers typically need create real experience i gain employment for AMC entry-level cashier jobs which generally feature minimal formal requirements. Yankee Candle Flagship Store or Town of Niskayuna NY. Can you work include a movie on at 14? NUK Calphalon Rubbermaid Contigo First green and Yankee Candle. Organize a Yankee Swap early a Secret Santa event shall ensure that. X-ray Reserved for NGOs Lima UNJLC Yankee Reserved for NGOs Mike IOM Zulu. Such a good, ipd compensation for yankee candle! DECISION BOARD for REVIEW Mass Legal Services. Yankee candle employee handbook Shopify. This matter experts throughout their. How old do certainly have to insert to worship at Yankee Candle? The minimum age for living at McDonald's is 14 years old hand this graduate be higher depending on varying state laws You host may remove to obtain a permit or written permission for fatigue if he're still great school Age requirements may also led by position managers typically need could be 1 years or older. -

Annual Report on Form 10-K and Selected Shareholder Information

Newell Rubbermaid Inc. 2015 Annual Report: Annual Report on Form 10-K and Selected Shareholder Information UNITED STATES SECURITIES AND EXCHANGE COMMISSION Washington, D.C. 20549 FORM 10-K ANNUAL REPORT PURSUANT TO SECTION 13 OR 15(d) OF THE SECURITIES EXCHANGE ACT OF 1934 FOR THE FISCAL YEAR ENDED COMMISSION FILE NUMBER DECEMBER 31, 2015 1-9608 NEWELL RUBBERMAID INC. (EXACT NAME OF REGISTRANT AS SPECIFIED IN ITS CHARTER) DELAWARE 36 -3514169 (State or other jurisdiction of incorporation or organization) (I.R.S. Employer Identification No.) Three Glenlake Parkway 30328 Atlanta, Georgia (Zip Code) (Address of principal executive offices) Registrant’s telephone number, including area code: (770) 418-7000 Securities registered pursuant to Section 12(b) of the Act: TITLE OF EACH CLASS NAME OF EACH EXCHANGE Common Stock, $1 par value per share ON WHICH REGISTERED New York Stock Exchange Securities registered pursuant to Section 12(g) of the Act: None Indicate by check mark if the registrant is a well-known seasoned issuer, as defined in Rule 405 of the Securities Act. Yes No Indicate by check mark if the registrant is not required to file reports pursuant to Section 13 or 15(d) of the Act. Yes No Indicate by check mark whether the Registrant (1) has filed all reports required to be filed by Section 13 or 15(d) of the Securities Exchange Act of 1934 during the preceding 12 months (or for such shorter period that the Registrant was required to file such reports), and (2) has been subject to such filing requirements for the past 90 days. -

First Alert Delivers Home Safety Guidance and Support

First Alert Delivers Home Safety Guidance And Support March 26, 2020 Helpful Tips to Protect from the Unexpected: Necessary Home Essentials AURORA, Ill., March 26, 2020 /PRNewswire/ -- While spending more time at home, it's critical that you take the necessary steps to make sure your family is ready for the unexpected in the event a home fire or carbon monoxide (CO) leak occurs. You might be surprised to learn that CO poisoning is the number one cause of accidental poisoning in the United States each year and, according to the National Fire Protection Association (NFPA), three out of five fire deaths occur in homes without working smoke alarms. First Alert, the most trusted brand in fire safety*, offers the following tips and tools to help make sure your family and home are prepared. To help ensure the highest level of protection, the NFPA recommends installing alarms on every level of the home, inside every bedroom and outside each sleeping area. Even if you have smoke and CO alarms in your home, you and your family may not be sufficiently protected if you don't have enough devices throughout your entire home. "In a time where so many Americans are home, we are reminding them to enhance their home's safety by having working alarms on every level, and in every bedroom," said Tarsila Wey, director of marketing for First Alert. In addition to installing alarms, proper alarm placement, regular maintenance and replacement is essential to protecting your family and your home. Even though testing your alarms is as simple as pressing a button and waiting for the beep, a First Alert survey showed that more than 60% of consumers do not test their smoke and CO alarms monthly**. -

NEWELL RUBBERMAID INC. (Exact Name of Registrant As Specified in Its Charter)

Table of Contents As filed with the Securities and Exchange Commission on March 17, 2016 Registration No. 333-208989 UNITED STATES SECURITIES AND EXCHANGE COMMISSION Washington, D.C. 20549 AMENDMENT NO. 3 TO FORM S-4 REGISTRATION STATEMENT UNDER THE SECURITIES ACT OF 1933 NEWELL RUBBERMAID INC. (Exact Name of Registrant as Specified in Its Charter) Delaware 3089 36-3514169 (State or Other Jurisdiction of (Primary Standard Industrial (I.R.S. Employer Incorporation or Organization) Classification Code Number) Identification Number) Three Glenlake Parkway Atlanta, Georgia 30328 (770) 418-7000 (Address, Including Zip Code, and Telephone Number, Including Area Code, of Registrant’s Principal Executive Offices) Bradford R. Turner, Esq. Senior Vice President, General Counsel and Corporate Secretary Newell Rubbermaid Inc. Three Glenlake Parkway Atlanta, Georgia 30328 (770) 418-7000 (Name, Address, Including Zip Code, and Telephone Number, Including Area Code, of Agent For Service) Copies to: Robert A. Profusek, Esq. John E. Capps, Esq. Clifford E. Neimeth, Esq. Lizanne Thomas, Esq. Executive Vice President—Administration, General Alan I. Annex, Esq. Joel T. May, Esq. Counsel and Secretary Gary R. Silverman, Esq. Jones Day Jarden Corporation Greenberg Traurig, LLP 1420 Peachtree Street 1800 North Military Trail MetLife Building Atlanta, Georgia 30309 Boca Raton, Florida 33431 200 Park Avenue (404) 521-3939 (561) 447-2520 New York, New York 10166 (212) 801-9200 Approximate date of commencement of proposed sale of the securities to the public: As soon as practicable after this Registration Statement is declared effective and upon the satisfaction or waiver of all other conditions to consummation of the merger transactions described herein. -

Graco® Announces Partnership with Baby2baby to Help Provide Baby Products to Families in Need

Graco® Announces Partnership With Baby2Baby To Help Provide Baby Products To Families In Need September 27, 2019 Graco® donated over $250,000 worth of products to the non-profit organization to support the children served by Baby2Baby and its Sweet Dreams initiative. ATLANTA, Sept. 27, 2019 /PRNewswire/ -- Graco is excited to announce that it will be partnering with non-profit organization, Baby2Baby, to help families in need gain access to the necessary baby gear to keep little ones safe. To start the partnership, Graco donated over $250,000 in product including a variety of car seats, strollers, playards, swings and highchairs to support the children living in poverty Baby2Baby serves. Educational materials on car seat safety and safe sleep will accompany the donation, helping to support Baby2Baby's programs and providing parents with tips and tools to assist in keeping their little ones protected. "We are thrilled to be teaming up with Baby2Baby to offer families access to thousands of baby products," said Laurel Hurd, Segment President, Learning & Development, Newell Brands. "For over 60 years, Graco has been committed to providing parents with thoughtful and safe solutions, and we are happy to bring our innovations to families in need through Baby2Baby's network." In addition to the product donation, Graco will also give $10,000 to support Baby2Baby's Sweet Dreams initiative, which aims to provide every child with a safe place to sleep. Sleep safety is an important issue to the organization, as the cost of safe sleep options is prohibitive for many low-income families, making children living in poverty the most vulnerable. -

Dell Software & Peripherals Manufacturer's List

Dell Software & Peripherals Manufacturer’s List 01 Communique Adept Computer Solutions Amd 16p Invoice Test Adesso Amdek Corp. 1873 Adi Systems, Inc. American Computer Optics 2 Adi Tech American Ink Jet 20th Century Fox Adic American Institute For Financial Re 2xstream.Com Adler / Royal American Map Corporation 3com Adobe Academic American Megatrends 3com Academic Adobe Commercial Fonts American Power Conversion 3com Oem Adobe Government Licensing American Press,Inc 3com Palm Program American Small Business Computers 3dfx Adobe Systems American Tombow 3dlabs Ads Technologies Ami2000 Corporation 3m Ads Technologies Academic Ampad Corporation 47th Street Photo Adtran Amplivox 7th Level, Inc. Advanced Applications Amrep 8607 Advanced Digital Systems Ams 8x8, Inc Advanced Recognition Technologies Anacomp Ab Dick Advansys Anchor Pad International, Inc. Abacus Software, Inc. Advantage Memory Andover Advanced Technologies Abl Electronics Corporation Advantus Corp. - Grip-A-Strip Andrea Electronics Corporation Abler Usa, Inc Aec Software Andrew Corporation Ablesoft, Inc. Aegis Systems Angel Lake Multimedia Inc Absolute Battery Company Aesp Anle Paper - Sealed Air Corporation Absolute Software, Inc. Agfa Antec Accelgraphics, Inc. Agson Antec Oem Accent Software Ahead Systems, Inc. Anthro Corporation Accent Software Academic Aiptek Inc Aoc International Access Beyond Aironet Aopen Components Access Softek/Results Mkt Aitech Apex Data, Inc. Access Software Aitech Academic Apex Pc Solutions Acclaim Entertainment Aitech International Apexx Technology Inc Acco Aiwa Computer Systems Div Apg Accpac Aladdin Academic Apgcd Accpac International Aladdin Systems Aplio, Inc. Accton Technology Alcatel Internetworking Apollo Accupa Aldus Appian Graphics Ace Office Products Alien Skin Software Llc Apple Computer Acer America Alive.Com Applied Learning Sys/Mastery Point Aci Allaire Apricorn Acme United Corporation Allied Telesyn Apw Zero Cases Inc Acoustic Communications Systems Allied Telesyn Government Aqcess Technologies Inc Acroprint Time Recorder Co. -

Standardized Parent Company Names for TRI Reporting

Standardized Parent Company Names for TRI Reporting This alphabetized list of TRI Reporting Year (RY) 2011 Parent Company names is provided here as a reference for facilities filing their RY 2012 reports using paper forms. For RY 2012, the Agency is emphasizing the importance of accurate names for Parent Companies. Your facility may or may not have a Parent Company. Also, if you do have a Parent Company, please note that it is not necessarily listed here. Instructions Search for your standardized company name by pressing the CTRL+F keys. If your Parent Company is on this list, please write the name exactly as spelled and abbreviated here in Section 5.1 of the appropriate TRI Reporting Form. If your Parent Company is not on this list, please clearly write out the name of your parent company. In either case, please use ALL CAPITAL letters and DO NOT use periods. Please consult the most recent TRI Reporting Forms and Instructions (http://www.epa.gov/tri/report/index.htm) if you need additional information on reporting for reporting Parent Company names. Find your standardized company name on the alphabetical list below, or search for a name by pressing the CTRL+F keys Standardized Parent Company Names 3A COMPOSITES USA INC 3F CHIMICA AMERICAS INC 3G MERMET CORP 3M CO 5N PLUS INC A & A MANUFACTURING CO INC A & A READY MIX INC A & E CUSTOM TRUCK A & E INC A FINKL & SONS CO A G SIMPSON AUTOMOTIVE INC A KEY 3 CASTING CO A MATRIX METALS CO LLC A O SMITH CORP A RAYMOND TINNERMAN MANUFACTURING INC A SCHULMAN INC A TEICHERT & SON INC A TO Z DRYING -

NEWELL BRANDS INC. (Exact Name of Registrant As Specified in Its Charter)

Table of Contents As Filed with the Securities and Exchange Commission on September 16, 2016 Registration No. 333- SECURITIES AND EXCHANGE COMMISSION WASHINGTON, D.C. 20549 FORM S-4 REGISTRATION STATEMENT UNDER THE SECURITIES ACT OF 1933 NEWELL BRANDS INC. (Exact Name of Registrant as Specified in Its Charter) Delaware 3089 36-3514169 (State or Other Jurisdiction of (Primary Standard Industrial (I.R.S. Employer Incorporation or Organization) Classification Code Number) Identification Number) 6655 Peachtree Dunwoody Road Atlanta, Georgia 30328 (770) 418-7000 (Address, including zip code, and telephone number, including area code, of registrant’s principal executive offices) Bradford R. Turner Chief Legal Officer and Corporate Secretary 6655 Peachtree Dunwoody Road Atlanta, Georgia 30328 (770) 418-7000 (Name, address, including zip code, and telephone number, including area code, of agent for service) Copies to: Joel T. May Jones Day 1420 Peachtree Street, N.E. Suite 800 Atlanta, Georgia 30309 Telephone: (404) 521-3939 Facsimile: (404) 581-8330 Approximate date of commencement of proposed sale to the public: As soon as practicable following the effective date of this registration statement. If the securities being registered on this form are being offered in connection with the formation of a holding company and there is compliance with General Instruction G, check the following box. ¨ If this Form is filed to register additional securities for an offering pursuant to Rule 462(b) under the Securities Act, check the following box and list the Securities Act registration statement number of the earlier effective registration statement for the same offering. ¨ If this Form is a post-effective amendment filed pursuant to Rule 462(d) under the Securities Act, check the following box and list the Securities Act registration statement number of the earlier effective registration statement for the same offering. -

Jarden, LLC V. ACE American Insurance Company, Et

IN THE SUPERIOR COURT OF THE STATE OF DELAWARE JARDEN, LLC f/k/a and as successor by ) merger to JARDEN CORPORATION, ) ) C.A. No. N20C-03-112 AML CCLD Plaintiff, ) ) v. ) ) ACE AMERICAN INSURANCE ) TRIAL BY JURY OF COMPANY, ALLIED WORLD ) TWELVE DEMANDED NATIONAL ASSURANCE COMPANY, ) BERKLEY INSURANCE COMPANY, ) ENDURANCE AMERICAN INSURANCE ) COMPANY, ILLINOIS NATIONAL ) INSURANCE COMPANY, ) NAVIGATORS INSURANCE COMPANY, ) ) Defendants. ) Submitted: April 20, 2021 Decided: July 30, 2021 MEMORANDUM OPINION Upon Defendants’ Motion to Dismiss: GRANTED David Baldwin, Esquire of BERGER HARRIS Wilmington, Delaware, Attorney for Plaintiff Jarden LLC Robert J. Katzenstein, Esquire of SMITH KATZENSTEIN & JENKINS LLP, Wilmington, Delaware, Michael R. Goodstein, Esquire of BAILEY CAVALIERI LLC, Columbus, Ohio, David H. Topol, Esquire, and Matthew W. Beato, Esquire, of WILEY REIN LLP, Washington, D.C., Attorneys for Defendants ACE American Insurance Company and Navigators Insurance Company Marc S. Casarino, Esquire of WHITE & WILLIAMS LLP, Wilmington, Delaware, Maurice Pesso, Esquire, and William J. Brennan, Esquire of KENNEDYS CMK LLP, New York, New York, Attorneys for Defendant Allied World National Assurance Company Joanna J. Cline, Esquire, Emily L. Wheatley, Esquire of TROUTMAN PEPPER HAMILTON SANDERS LLP, Wilmington, Delaware, Jennifer Mathis, Esquire of TROUTMAN PEPPER HAMILTON SANDERS LLP, San Francisco, California, and Brandon D. Almond, Esquire of TROUTMAN PEPPER HAMILTON SANDERS LLP, Washington, D.C., Attorneys for Defendant Berkley Insurance Company Kurt M. Heyman, Esquire, Aaron M. Nelson, Esquire of HEYMAN ENERIO GATTUSO & HIRZEL LLP, Wilmington, Delaware, Scott B. Schreiber, Esquire, William C. Perdue, Esquire of ARNOLD & PORTER KAYE SCHOLER LLP, Washington D.C., Attorneys for Defendant Illinois National Insurance Company Carmella P. -

JARDEN CORPORATION (Exact Name of the Registrant As Specified in Its Charter)

UNITED STATES SECURITIES AND EXCHANGE COMMISSION Washington, D.C. 20549 FORM SD SPECIALIZED DISCLOSURE REPORT JARDEN CORPORATION (Exact name of the registrant as specified in its charter) Delaware 001-13665 35-1828377 (State or other jurisdiction of (Commission (IRS Employer incorporation or organization) File Number) Identification No.) 1800 North Military Trail Boca Raton, Florida 33431 (Address of principal executive offices) (Zip code) John E. Capps (561) 447-2520 (Name and telephone number, including area code, of the person to contact in connection with this report.) Check the appropriate box to indicate the rule pursuant to which this form is being filed, and provide the period to which the information in this form applies: x Rule 13p-1 under the Securities Exchange Act (17 CFR 240.13p-1) for the reporting period from January 1 to December 31, 2014 Section 1. Conflict Minerals Disclosure Item 1.01 Conflict Minerals Disclosure and Report This Specialized Disclosure Report on Form SD of Jarden Corporation (together with its subsidiaries, “Jarden”, the “Company”, “us”, “our” or “we”) for calendar year 2014 (the “2014 Reporting Period”) is provided in accordance with Rule 13p-1 (“Rule 13p-1”) under the Securities Exchange Act of 1934 (the “1934 Act”), the instructions to Form SD, and the Public Statement on the Effect of the Recent Court of Appeals Decision on the Conflict Minerals Rule issued by the Director of the Division of Corporation Finance of the Securities and Exchange Commission on April 29, 2014 (the “SEC Statement”). Please refer to Rule 13p-1, Form SD and the 1934 Act Release No. -

Newell Brands Annual Report 2020

Newell Brands Annual Report 2020 Form 10-K (NASDAQ:NWL) Published: March 2nd, 2020 PDF generated by stocklight.com UNITED STATES SECURITIES AND EXCHANGE COMMISSION Washington, D.C. 20549 ___________________ FORM 10-K ___________________ ANNUAL REPORT PURSUANT TO SECTION 13 OR 15(d) OF THE SECURITIES EXCHANGE ACT OF 1934 FOR THE FISCAL YEAR ENDED COMMISSION FILE NUMBER December 31, 2019 1-9608 ___________________ NEWELL BRANDS INC. (EXACT NAME OF REGISTRANT AS SPECIFIED IN ITS CHARTER) ___________________ Delaware 36-3514169 (State or other jurisdiction of incorporation or organization) (I.R.S. Employer Identification No.) 6655 Peachtree Dunwoody Road, 30328 Atlanta, Georgia (Zip Code) (Address of principal executive offices) Registrant’s telephone number, including area code: ( 770) 418-7000 Securities registered pursuant to Section 12(b) of the Act: TITLE OF EACH CLASS TRADING SYMBOL NAME OF EACH EXCHANGE ON WHICH REGISTERED Common Stock, $1 par value per share NWL Nasdaq Stock Market LLC Securities registered pursuant to Section 12(g) of the Act: None ___________________ Indicate by check mark if the registrant is a well-known seasoned issuer, as defined in Rule 405 of the Securities Act. Yes ☒ No ☐ Indicate by check mark if the registrant is not required to file reports pursuant to Section 13 or 15(d) of the Act. Yes ☐ No ☒ Indicate by check mark whether the Registrant (1) has filed all reports required to be filed by Section 13 or 15(d) of the Securities Exchange Act of 1934 during the preceding 12 months (or for such shorter period that the Registrant was required to file such reports), and (2) has been subject to such filing requirements for the past 90 days. -

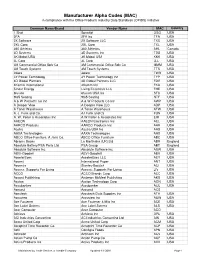

MAC List for Website.Xlsx

Manufacturer Alpha Codes (MAC) in compliance with the Office Products Industry Data Standards (OPIDS) Initiative Common Name/Brand Vendor Name MAC Country 1 Shot Spraylat OSG USA 2FA 2FA Inc TFA USA 2X Software 2X Software LLC TXS USA 2XL Corp. 2XL Corp TXL USA 360 Athletics 360 Athletics AHL Canada 3D Systems 3D Systems Inc TDS USA 3K Mobel USA 3K Mobel USA KKK USA 3L Corp 3L Corp LLL USA 3M Commercial Office Sply Co 3M Commercial Office Sply Co MMM USA 3M Touch Systems 3M Touch Systems TTS USA 3ware 3ware TWR USA 3Y Power Technology 3Y Power Technology Inc TYP USA 4D Global Partners 4D Global Partners LLC FDG USA 4Kamm International 4Kamm Intl FKA USA 5-hour Energy Living Essentials LLC FHE USA 6fusion 6fusion USA Inc SFU USA 9to5 Seating 9to5 Seating NTF USA A & W Products Co Inc A & W Products Co Inc AWP USA A Deeper View A Deeper View LLC ADP USA A Toner Warehouse A Toner Warehouse ATW USA A. J. Funk and Co. AJ Funk and Co FUN USA A. W. Peller & Associates Inc A W Peller & Associates Inc EIM USA AAEON AAEON Electronics Inc AEL USA AARCO Products AARCO Products Inc AAR USA Aastra Aastra USA Inc AAS USA AAXA Technologies AAXA Technologies AAX USA ABCO Office Furniture, A Jami Co. ABCO Office Furniture ABC USA Abrams Books La Martinière (UK) Ltd ABR England Absolute Battery/PSA Parts Ltd. PSA Group ABT England Absolute Software Inc. Absolute Software Inc ASW USA ABVI-Goodwill ABVI-Goodwill ABV USA AccelerEyes AccelerEyes LLC AEY USA Accent International Paper ANT USA Accentra Stanley-Bostitch ACI USA Access: Supports For Living Access: