On Fiona Apple's Tidal

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Daft Punk Collectible Sales Skyrocket After Breakup: 'I Could've Made

BILLBOARD COUNTRY UPDATE APRIL 13, 2020 | PAGE 4 OF 19 ON THE CHARTS JIM ASKER [email protected] Bulletin SamHunt’s Southside Rules Top Country YOURAlbu DAILYms; BrettENTERTAINMENT Young ‘Catc NEWSh UPDATE’-es Fifth AirplayFEBRUARY 25, 2021 Page 1 of 37 Leader; Travis Denning Makes History INSIDE Daft Punk Collectible Sales Sam Hunt’s second studio full-length, and first in over five years, Southside sales (up 21%) in the tracking week. On Country Airplay, it hops 18-15 (11.9 mil- (MCA Nashville/Universal Music Group Nashville), debutsSkyrocket at No. 1 on Billboard’s lion audience After impressions, Breakup: up 16%). Top Country• Spotify Albums Takes onchart dated April 18. In its first week (ending April 9), it earned$1.3B 46,000 in equivalentDebt album units, including 16,000 in album sales, ac- TRY TO ‘CATCH’ UP WITH YOUNG Brett Youngachieves his fifth consecutive cording• Taylor to Nielsen Swift Music/MRCFiles Data. ‘I Could’veand total Made Country Airplay No.$100,000’ 1 as “Catch” (Big Machine Label Group) ascends SouthsideHer Own marks Lawsuit Hunt’s in second No. 1 on the 2-1, increasing 13% to 36.6 million impressions. chartEscalating and fourth Theme top 10. It follows freshman LP BY STEVE KNOPPER Young’s first of six chart entries, “Sleep With- MontevalloPark, which Battle arrived at the summit in No - out You,” reached No. 2 in December 2016. He vember 2014 and reigned for nine weeks. To date, followed with the multiweek No. 1s “In Case You In the 24 hours following Daft Punk’s breakup Thomas, who figured out how to build the helmets Montevallo• Mumford has andearned Sons’ 3.9 million units, with 1.4 Didn’t Know” (two weeks, June 2017), “Like I Loved millionBen in Lovettalbum sales. -

SHAKE YOUR FAITH Diamond Day Records Is Very Excited to Announce the Release of the Steepwater Band’S 6Th Full-Length Studio Album SHAKE YOUR FAITH

THE STEEPWATER BAND : SHAKE YOUR FAITH Diamond Day Records is very excited to announce the release of The Steepwater Band’s 6th full-length studio album SHAKE YOUR FAITH. The LP features 11 brand new TSB tracks, and is slated for release on Friday, April 1st via Double 180 Gram Vinyl, Compact Disc and Digital Download. The album was recorded last winter at Crushtone Studios, in the shadows of the Rock & Roll Hall of Fame, in Cleveland, Ohio. Shake Your Faith was produced by the band along with seasoned rock studio veteran Jim Wirt, who has also worked with the likes of Fiona Apple, Incubus and the Buffalo Killers. As with most TSB albums, the sound and songwriting on Shake Your Faith has grown and expanded, yet retained the true nature of the band. It’s the first TSB studio record in over 4 years and the first to include “new” guitarist Eric Saylors. "SHAKE YOUR FAITH is a stomping, seductive cry that real rock 'n' roll is alive and well in a band with the swagger, justified confidence, and badass tunes of a modern classic, a collection with all the heart and hips of 70s Stones and serious competition to contemporaries like The Black Keys, Ben Harper, and Jack White." - Dennis Cook {Dirty Impound} • Their song “Dance Me a Number” from Revelation Sunday receives nearly 10,000 spins on Pandora daily, on such channels as The Black Keys, Alabama Shakes, White Stripes, Led Zeppelin, and more. • Their 2010 single The Stars Look Good Tonight reached # 109 on the Triple A radio charts and it was featured during the June 29, 2010, WGN-TV (nationally syndicated) broadcast of the Chicago Cubs Major League Baseball game. -

By Fiona Apple)

April 15, 2021 For Immediate Release Sharon Van Etten Reveals “Love More” (By Fiona Apple) epic Ten Out Tomorrow on Ba Da Bing; Anniversary Double Album Featuring Covers by Fiona Apple, Lucinda Williams, Big Red Machine (Aaron Dessner & Justin Vernon), Courtney Barnett . Vagabon, IDLES, Shamir, and St. Panther epic Ten: the documentary and concert Benefiting Zebulon Streaming April 16th & April 17th Sharon Van Etten live from Zebulon in LA / Photo Credit: still taken from the epic Ten documentary and concert Tomorrow, Sharon Van Etten will release epic Ten via Ba Da Bing (physical copies will be available June 11th). Today, she reveals its last cover, “Love More” (By Fiona Apple). epic Ten is a double LP of the original epic album from 2010 and a new album of epic covers by Fiona Apple, Lucinda Williams, Courtney Barnett . Vagabon, Big Red Machine (Aaron Dessner & Justin Vernon), IDLES, Shamir and St. Panther. Each Thursday leading up to its release, Van Etten has been sharing the album’s consecutive cover songs, culminating into today’s cover -- “Love More” (By Fiona Apple). Ahead of tomorrow’s epic Ten release, read Adrianne Lenker’s wonderful liner notes, included below. Listen to “Love More” (By Fiona Apple) epic Ten: the accompanying documentary and concert will stream starting tomorrow through April 17th (stream times are below). Van Etten and her band will perform epic in its entirety from Zebulon LA, the venue that played a crucial role in her early career, with profits benefiting Zebulon. A short documentary on the making of epic and the significance of Zebulon as a haven for Van Etten and many other musicians will be presented before the concert. -

Led Zeppelin R.E.M. Queen Feist the Cure Coldplay the Beatles The

Jay-Z and Linkin Park System of a Down Guano Apes Godsmack 30 Seconds to Mars My Chemical Romance From First to Last Disturbed Chevelle Ra Fall Out Boy Three Days Grace Sick Puppies Clawfinger 10 Years Seether Breaking Benjamin Hoobastank Lostprophets Funeral for a Friend Staind Trapt Clutch Papa Roach Sevendust Eddie Vedder Limp Bizkit Primus Gavin Rossdale Chris Cornell Soundgarden Blind Melon Linkin Park P.O.D. Thousand Foot Krutch The Afters Casting Crowns The Offspring Serj Tankian Steven Curtis Chapman Michael W. Smith Rage Against the Machine Evanescence Deftones Hawk Nelson Rebecca St. James Faith No More Skunk Anansie In Flames As I Lay Dying Bullet for My Valentine Incubus The Mars Volta Theory of a Deadman Hypocrisy Mr. Bungle The Dillinger Escape Plan Meshuggah Dark Tranquillity Opeth Red Hot Chili Peppers Ohio Players Beastie Boys Cypress Hill Dr. Dre The Haunted Bad Brains Dead Kennedys The Exploited Eminem Pearl Jam Minor Threat Snoop Dogg Makaveli Ja Rule Tool Porcupine Tree Riverside Satyricon Ulver Burzum Darkthrone Monty Python Foo Fighters Tenacious D Flight of the Conchords Amon Amarth Audioslave Raffi Dimmu Borgir Immortal Nickelback Puddle of Mudd Bloodhound Gang Emperor Gamma Ray Demons & Wizards Apocalyptica Velvet Revolver Manowar Slayer Megadeth Avantasia Metallica Paradise Lost Dream Theater Temple of the Dog Nightwish Cradle of Filth Edguy Ayreon Trans-Siberian Orchestra After Forever Edenbridge The Cramps Napalm Death Epica Kamelot Firewind At Vance Misfits Within Temptation The Gathering Danzig Sepultura Kreator -

DYLAN RYAN / SAND Title: CIRCA (Cuneiform Rune 397) Format: CD / DIGITAL

Bio information: DYLAN RYAN / SAND Title: CIRCA (Cuneiform Rune 397) Format: CD / DIGITAL Cuneiform promotion dept: (301) 589-8894 / fax (301) 589-1819 email: joyce [-at-] cuneiformrecords.com (Press & world radio); radio [-at-] cuneiformrecords.com (North American & world radio) www.cuneiformrecords.com FILE UNDER: JAZZ / ELECTRIC JAZZ / ROCK Dylan Ryan’s LA Guitar Power Trio with Timothy Young and Devin Hoff, – Dylan Ryan / Sand – Returns with a New Album, Circa, A Musically and Emotionally Evocative, Guitar-Drenched Disc Born on the Road and in Moonlight, in Caves on Libyan Sea Shores Los Angeles, CA is home base for one of the most inventive and musically awesome guitar power trios on the current electric jazz and rock scenes: Dylan Ryan / Sand. Led by Dylan Ryan, a drummer/composer with feet firmly planted in both indie rock and jazz, the group features guitarist Timothy Young (David Sylvian, Reggie Watts, Wayne Horvitz) and Devin Hoff (Nels Cline Singers, Yoko Ono, Cibo Matto). Together on Circa, their second release on Cuneiform Records, the trio forge a wholly unique, emotionally-charged and stylistically omnivorous music that invokes elements of Rush, Fugazi, Fred Frith’s Massacre, James ‘Blood’ Ulmer, and more, and sonically ranges from fearlessly improvisational to tender; the abrasive to the understated. Indeed, this range of influences and openness to sonic possibilities is what initially drew Ryan to his bandmates. “I saw Tim Young play somewhat by chance in an old bar The Doors used to play in and I was so impressed that I wanted to be in a band with him immediately. -

The Wallflowers "Exit Wounds" Press Release

THE WALLFLOWERS RETURN WITH EXIT WOUNDS JULY 9th VIA NEW WEST RECORDS FIRST ALBUM IN NEARLY A DECADE PRODUCED BY BUTCH WALKER AND FEATURES SHELBY LYNNE PERFORM FIRST SINGLE “ROOTS AND WINGS” ON JIMMY KIMMEL LIVE! LAST NIGHT ANNOUNCE 53-DATE ARENA TOUR LAUNCHING JULY 16th The Wallflowers will release Exit Wounds on July 9th via New West Records. The 10-song set is their first album in nearly a decade and was produced by Butch Walker (Taylor Swift, Weezer). Exit Wounds was mixed by Chris Dugan (Green Day) and features the acclaimed singer-songwriter Shelby Lynne on four songs. While it’s been nearly a decade since we’ve heard from the group with whom Jakob Dylan first made his mark, he always knew they’d return. “The Wallflowers is much of my life’s work,” he says simply. The much-anticipated record finds the band’s signature sound — lean, potent and eminently entrancing — intact. The Wallflowers announced their return with a live performance of the first single “Roots and Wings” last night on ABC’s Jimmy Kimmel Live! See the performance HERE. For the past 30 years, The Wallflowers have stood as one of rock’s most dynamic and purposeful bands — a unit dedicated to and continually honing a sound that meshes timeless songwriting and storytelling with a hard-hitting and decidedly modern musical attack. That signature style has been present through the decades, baked into the grooves of smash hits like 1996’s Bringing Down the Horse as well as more recent and exploratory fare like 2012’s Glad All Over. -

Aural Skills I Toby Rush Using Solfege, Transcribe the Vocal Parts To

Assignment #1 Name ___________________________ Aural Skills I Toby Rush Using solfege, transcribe the vocal parts to “e Sidewalks Of New York,” by James W. Blake and Charles B. Lawlor, as performed by Larry Groce on the Walt Disney album series Children’s Favorite Songs. Groce’s recording of this early-twentieth-century popular song omits the verses included in the original, and features the chorus song twice through. While the original was written in past tense, as a nostalgic remembrance of Blake’s childhood in the 1890s, Groce uses present tense (“e tots sing” and “Trip the light fantastic” rather than “e tots sang” and “Tripped the light fantastic”) to invite the listener into the scene. Complete the transcription in the chart on the following page. You need only transcribe the melody as sung by Groce; you do not need to notate the harmonies sung by the children’s chorus. Larry Groce: East Side, West Side, all a- round the town e tots sing “ring- a ro- sie,” “Lon- don Bridge is fall- ling down” Boys and girls to- geth- er, me and Ma- mie O’- Rourke Trip the light fan- tas- tic on the side- walks of New York Assignment #2 Name ___________________________ Aural Skills I Toby Rush Transcribe the rhythm of the melody of “Come ou Fount Of Every Blessing,” by Robert Robinson, as performed by Suan Stevens on the album Hark! Songs for Christmas. For this transcription, you need to write the rhythm of only the !rst verse. Write only the rhythms of the lead vocal line. -

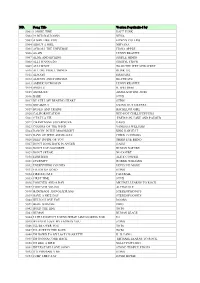

POP Vol 1 Song List

NO. Song Title Version Popularized by 5001 1 MORE TIME DAFT FUNK 5002 99 RED BALLOONS NENA 5003 A GIRL LIKE YOU EDWYN COLLINS 5004 ABOUT A GIRL NIRVANA 5005 ACROSS THE UNIVERSE FIONA APPLE 5006 AGAIN LENNY KRAVITZ 5007 ALIVE AND KICKING SIMPLE MINDS 5008 ALL I WANNA DO SHERYL CROW 5009 ALL I WANT TOAD THE WET SPROCKET 5010 ALL THE SMALL THINGS BLINK 182 5011 ALWAYS ERASURE 5012 ALWAYS AND FOREVER HEATWAVE 5013 AMERICAN WOMAN LENNY KRAVITZ 5014 ANGELS R. WILLIMAS 5015 ANTMUSIC ADAM AND THE ANTS 5016 BABE STYX 5017 BE STILL MY BEATING HEART STING 5018 BREAKOUT SWING OUT SISTERS 5019 BUSES AND TRAINS BACHELOR GIRL 5020 CALIFORNICATION RED HOT CHILLI PEPPERS 5021 C’EST LA VIE EMERSON, LAKE AND PALMER 5022 CHAMPAGNE SUPERNOVA OASIS 5023 COLORS OF THE WIND VANESSA WILLIAMS 5024 DANCIN’ IN THE MOONLIGHT KING HARVEST 5025 DAYS OF WINE AND ROSES CHRIS CONNORS 5026 DEEP INSIDE OF YOU THIRD EYE BLIND 5027 DON’T LOOK BACK IN ANGER OASIS 5028 DON’T SAY GOODBYE HUMAN NATURE 5029 DON’T SPEAK NO DOUBT 5030 EIGHTEEN ALICE COOPER 5031 ETERNITY ROBBIE WILLIAMS 5032 EVERYTHING COUNTS DEPECHE MODE 5033 FIELDS OF GOLD STING 5034 FIRE ESCAPE FASTBALL 5035 FIRST TIME STYX 5036 FOREVER AND A DAY MICHAEL LEARNS TO ROCK 5037 FOREVER YOUNG ALPHAVILLE 5038 HANDBAGS AND GLADRAGS STEREOPHONICS 5039 HAVE A NICE DAY STEREOPHONICS 5040 HELLO I LOVE YOU DOORS 5041 HERE WITH ME DIDO 5042 HOLD THE LINE TOTO 5043 HUMAN HUMAN LEAGE 5044 I STILL HAVEN’T FOUND WHAT I AM LOOKING FOR U2 5045 IF I EVER LOSE MY FAITH IN YOU STING 5046 I’LL BE OVER YOU TOTO 5047 I’LL SUPPLY THE LOVE TOTO 5048 I’M DOWN TO MY LAST CIGARETTE K. -

Songs by Artist

Sound Master Entertianment Songs by Artist smedenver.com Title Title Title .38 Special 2Pac 4 Him Caught Up In You California Love (Original Version) For Future Generations Hold On Loosely Changes 4 Non Blondes If I'd Been The One Dear Mama What's Up Rockin' Onto The Night Thugz Mansion 4 P.M. Second Chance Until The End Of Time Lay Down Your Love Wild Eyed Southern Boys 2Pac & Eminem Sukiyaki 10 Years One Day At A Time 4 Runner Beautiful 2Pac & Notorious B.I.G. Cain's Blood Through The Iris Runnin' Ripples 100 Proof Aged In Soul 3 Doors Down That Was Him (This Is Now) Somebody's Been Sleeping Away From The Sun 4 Seasons 10000 Maniacs Be Like That Rag Doll Because The Night Citizen Soldier 42nd Street Candy Everybody Wants Duck & Run 42nd Street More Than This Here Without You Lullaby Of Broadway These Are Days It's Not My Time We're In The Money Trouble Me Kryptonite 5 Stairsteps 10CC Landing In London Ooh Child Let Me Be Myself I'm Not In Love 50 Cent We Do For Love Let Me Go 21 Questions 112 Loser Disco Inferno Come See Me Road I'm On When I'm Gone In Da Club Dance With Me P.I.M.P. It's Over Now When You're Young 3 Of Hearts Wanksta Only You What Up Gangsta Arizona Rain Peaches & Cream Window Shopper Love Is Enough Right Here For You 50 Cent & Eminem 112 & Ludacris 30 Seconds To Mars Patiently Waiting Kill Hot & Wet 50 Cent & Nate Dogg 112 & Super Cat 311 21 Questions All Mixed Up Na Na Na 50 Cent & Olivia 12 Gauge Amber Beyond The Grey Sky Best Friend Dunkie Butt 5th Dimension 12 Stones Creatures (For A While) Down Aquarius (Let The Sun Shine In) Far Away First Straw AquariusLet The Sun Shine In 1910 Fruitgum Co. -

Songs by Artist

Songs by Artist Title Title (Hed) Planet Earth 2 Live Crew Bartender We Want Some Pussy Blackout 2 Pistols Other Side She Got It +44 You Know Me When Your Heart Stops Beating 20 Fingers 10 Years Short Dick Man Beautiful 21 Demands Through The Iris Give Me A Minute Wasteland 3 Doors Down 10,000 Maniacs Away From The Sun Because The Night Be Like That Candy Everybody Wants Behind Those Eyes More Than This Better Life, The These Are The Days Citizen Soldier Trouble Me Duck & Run 100 Proof Aged In Soul Every Time You Go Somebody's Been Sleeping Here By Me 10CC Here Without You I'm Not In Love It's Not My Time Things We Do For Love, The Kryptonite 112 Landing In London Come See Me Let Me Be Myself Cupid Let Me Go Dance With Me Live For Today Hot & Wet Loser It's Over Now Road I'm On, The Na Na Na So I Need You Peaches & Cream Train Right Here For You When I'm Gone U Already Know When You're Young 12 Gauge 3 Of Hearts Dunkie Butt Arizona Rain 12 Stones Love Is Enough Far Away 30 Seconds To Mars Way I Fell, The Closer To The Edge We Are One Kill, The 1910 Fruitgum Co. Kings And Queens 1, 2, 3 Red Light This Is War Simon Says Up In The Air (Explicit) 2 Chainz Yesterday Birthday Song (Explicit) 311 I'm Different (Explicit) All Mixed Up Spend It Amber 2 Live Crew Beyond The Grey Sky Doo Wah Diddy Creatures (For A While) Me So Horny Don't Tread On Me Song List Generator® Printed 5/12/2021 Page 1 of 334 Licensed to Chris Avis Songs by Artist Title Title 311 4Him First Straw Sacred Hideaway Hey You Where There Is Faith I'll Be Here Awhile Who You Are Love Song 5 Stairsteps, The You Wouldn't Believe O-O-H Child 38 Special 50 Cent Back Where You Belong 21 Questions Caught Up In You Baby By Me Hold On Loosely Best Friend If I'd Been The One Candy Shop Rockin' Into The Night Disco Inferno Second Chance Hustler's Ambition Teacher, Teacher If I Can't Wild-Eyed Southern Boys In Da Club 3LW Just A Lil' Bit I Do (Wanna Get Close To You) Outlaw No More (Baby I'ma Do Right) Outta Control Playas Gon' Play Outta Control (Remix Version) 3OH!3 P.I.M.P. -

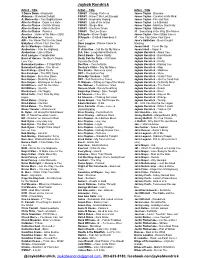

Got Me Wrong

Jaykob Kendrick Artist - Title Artist - Title Artist - Title 3 Doors Down - Kryptonite CSN&Y - Change Partners James Taylor - Blossom Alabama – Dixieland Delight CSN&Y - Haven't We Lost Enough James Taylor - Carolina in My Mind A. Morissette – You Oughta Know CSN&Y - Helplessly Hoping James Taylor - Fire and Rain Alice in Chains - Down in a Hole CSN&Y - Lady of the Island James Taylor - Lo & Behold Alice in Chains - Got Me Wrong CSN&Y - Simple Man James Taylor - Machine Gun Kelly Alice in Chains - Man in the Box CSN&Y - Southern Cross James Taylor - Millworker Alice in Chains - Rooster CSN&Y - The Lee Shore JT - Something in the Way She Moves America – Horse w/ No Name ($20) D’Angelo – Brown Sugar James Taylor - Sweet Baby James Amy Winehouse – Valerie D’Angelo – Untitled (How does it JT - You Can Close Your Eyes AW – You Know That I’m No Good feel?) Jane's Addiction - Been Caught Babyface - When Can I See You Dave Loggins - Please Come to Stealing Arctic Monkeys - Arabella Boston Jason Isbell – Cover Me Up Audioslave - I Am the Highway D. Allan Coe - Call Me By My Name Jason Isbell – Super 8 Audioslave - Like a Stone D.A. Coe - Long-Haired Redneck Jaykob Kendrick - About You Avril Lavigne - Complicated David Bowie - Space Oddity Jaykob Kendrick - Barrelhouse Band of Horses - No One's Gonna Death Cab for Cutie – I’ll Follow Jaykob Kendrick - Fall Love You You into the Dark Jaykob Kendrick - Firefly Barenaked Ladies – If I had $1M Des’Ree – You Gotta Be Jaykob Kendrick - Kissing You Barenaked Ladies - One Week Destiny’s Child – Say My Name Jaykob Kendrick - Map Ben E King – Stand By Me Dire Straits - Romeo & Juliet Jaykob Kendrick - Medicine Ben Erickson - The BBQ Song DBT – Decoration Day Jaykob Kendrick - Muse Ben Harper - Burn One Down Drive-By Truckers - Outfit Jaykob Kendrick - Nuckin' Futs Ben Harper - Steal My Kisses DBT - Self-Destructive Zones Jaykob Kendrick – On the Good Foot Ben Harper - Waiting on an Angel D. -

Tonal Ambiguity and Melodic-Harmonic Disconnect in the Music of Coldplay

“All That Noise, and All That Sound:” Tonal Ambiguity and Melodic-Harmonic Disconnect in the Music of Coldplay by Nathanael Welch Submitted in Partial Fulfillment of the Requirements for the Degree of Master of Music in the Music Theory and Composition Program YOUNGSTOWN STATE UNIVERSITY August, 2015 “All That Noise, and All That Sound:” Tonal Ambiguity and Melodic-Harmonic Disconnect in the Music of Coldplay Nathanael Welch I hereby release this thesis to the public. I understand that this thesis will be made available from the OhioLINK ETD Center and the Maag Library Circulation Desk for public access. I also authorize the University or other individuals to make copies of this thesis as needed for scholarly research. Signature: Nathanael Welch, Student Date Approvals: Dr. Jena Root, Thesis Advisor Date Dr. Randall Goldberg, Committee Member Date Dr. Tedrow Perkins, Committee Member Date Dr. Steven Reale, Committee Member Date Dr. Salvatore A. Sanders, Associate Dean of Graduate Studies Date i ABSTRACT Within the music of Coldplay there often exists a disconnect between the melody (vocal line) and the harmony (chord pattern/structure). It is often difficult to discern any tonal center (key) within a given song. In several of the songs I have selected for analysis, the melodies, when isolated from the harmonic patterns, suggest tonal centers at odds with the chords. Because of its often stratified pitch organization, Coldplay’s music is sometimes in two keys simultaneously. Exploring the disconnect between melody and harmony, I will show how that can lead to tonal ambiguity in the sense that there is no one key governing an entire song.