Ministry to Migrants and Asylum Seekers

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Issue 18 Midlands Arts 4:Layout 1

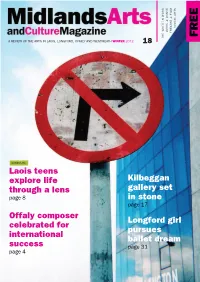

VISUAL ARTS MUSIC & DANCE ISSUE & FILM THEATRE FREE THE WRITTEN WORD A REVIEW OF THE ARTS IN LAOIS, LONGFORD, OFFALY AND WESTMEATH WINTER 2012 18 COVER PIC Laois teens explore life Kilbeggan through a lens gallery set page 8 in stone page 17 Offaly composer Longford girl celebrated for pursues international ballet dream success page 31 page 4 Toy Soldiers, wins at Galway Film Fleadh Midland Arts and Culture Magazine | WINTER 2010 Over two decades of Arts and Culture Celebrated with Presidential Visit ....................................................................Page 3 A Word Laois native to trend the boards of the Gaiety Theatre Midlands Offaly composer celebrated for international success .....Page 4 from the American publisher snaps up Longford writer’s novel andCulture Leaves Literary Festival 2012 celebrates the literary arts in Laois on November 9, 10............................Page 5 Editor Arts Magazine Backstage project sees new Artist in Residence There has been so Irish Iranian collaboration results in documentary much going on around production .....................................................................Page 6 the counties of Laois, Something for every child Mullingar Arts Centre! Westmeath, Offaly Fear Sean Chruacháin................................................Page 7 and Longford that County Longford writers honored again we have had to Laois teens explore life through the lens...............Page 8 up the pages from 32 to 36 just to fit Introducing Pete Kennedy everything in. Making ‘Friends’ The Doctor -

A S H E T News

1 ASHET News October 2009 Volume 2, number 4 ASHET News October 2009 Newsletter of the Australian Society for History of Engineering and Technology together from strips of fabric. It has vents at the top, controlled by cables ASHET members only tour to from the basket, to let out some of the hot air for the balloon and allow Kavanagh Balloons the balloon to descend. The basket below the balloon is made from wicker, the traditional At Mount Kuringai on the edge material, on a metal frame. Phil has on his staff a basket-weaver who of Sydney is the factory of builds these. The largest ones he makes will hold twelve passengers as Kavanagh Balloons that a party well as the cylinders of LPG fuel. The fuel burners, also made in the of ASHET members visited on factory, are mounted above the basket in the mouth of the balloon itself. 17 September. We saw here how Most balloons are decorated in unique designs made in coloured nylon Phil Kavanagh and a handful of fabric stitched to the panels of fabric that make up the balloon before they employees make their big hot air are assembled. The patterns for the decorative pieces are generated on a balloons. Just how big they are computer. Almost every aspect of the design and manufacture of these can be seen from the photo of balloons is carried out in this little factory. one that dwarfs the two storey Phil Kavanagh himself conducted our tour.. We were fascinated to factory building and the people see how modern techniques and materials are being used to build on an around it. -

Orme) Wilberforce (Albert) Raymond Blackburn (Alexander Bell

Copyrights sought (Albert) Basil (Orme) Wilberforce (Albert) Raymond Blackburn (Alexander Bell) Filson Young (Alexander) Forbes Hendry (Alexander) Frederick Whyte (Alfred Hubert) Roy Fedden (Alfred) Alistair Cooke (Alfred) Guy Garrod (Alfred) James Hawkey (Archibald) Berkeley Milne (Archibald) David Stirling (Archibald) Havergal Downes-Shaw (Arthur) Berriedale Keith (Arthur) Beverley Baxter (Arthur) Cecil Tyrrell Beck (Arthur) Clive Morrison-Bell (Arthur) Hugh (Elsdale) Molson (Arthur) Mervyn Stockwood (Arthur) Paul Boissier, Harrow Heraldry Committee & Harrow School (Arthur) Trevor Dawson (Arwyn) Lynn Ungoed-Thomas (Basil Arthur) John Peto (Basil) Kingsley Martin (Basil) Kingsley Martin (Basil) Kingsley Martin & New Statesman (Borlasse Elward) Wyndham Childs (Cecil Frederick) Nevil Macready (Cecil George) Graham Hayman (Charles Edward) Howard Vincent (Charles Henry) Collins Baker (Charles) Alexander Harris (Charles) Cyril Clarke (Charles) Edgar Wood (Charles) Edward Troup (Charles) Frederick (Howard) Gough (Charles) Michael Duff (Charles) Philip Fothergill (Charles) Philip Fothergill, Liberal National Organisation, N-E Warwickshire Liberal Association & Rt Hon Charles Albert McCurdy (Charles) Vernon (Oldfield) Bartlett (Charles) Vernon (Oldfield) Bartlett & World Review of Reviews (Claude) Nigel (Byam) Davies (Claude) Nigel (Byam) Davies (Colin) Mark Patrick (Crwfurd) Wilfrid Griffin Eady (Cyril) Berkeley Ormerod (Cyril) Desmond Keeling (Cyril) George Toogood (Cyril) Kenneth Bird (David) Euan Wallace (Davies) Evan Bedford (Denis Duncan) -

Index of Castlebar Parish Magazine 1971

Index of Castlebar Parish Magazine 1971 1. Parish Roundup & review of the past twelve months. Tom Courell 2. St. Gerald’s College – Short History Brother Vincent 3. Tribute to Walter Cowley, Vocational Teacher Sean O’Regan 4. Memories from School – Articles & Poems A) An old man remembers French Hill 1798. B) Poem “Old School Round the Corner” by pupils of 6th class, Errew School. C) Poem “ The Mall in Winter” by Ann Kelly, aged 12. D) Poem “ Nightfall in Sionhill” by Bridie Flannery, aged 12. E) Poem “Tanseys Bus Stop” by Gabrielle O’Farrell, aged 11. F) Poem “The Mall in November” by Kathryn Kilroy, aged 12. G) Poem “ The Station” by Eimear O’Meara, aged 11. H) Poem “St. Anthony’s School” by Mairin Feighan, aged 11. I) The Gossip in Town by Grainne Fadden, aged 12. J) Kinturk Castle by Ann Garvey, Carmel Mugan & Gabrielle Thomas. K) Description of Ballyheane by Geraldine Kelly, aged 12. L) Sean na Sagart by pupils of 5th class, Ballyheane N.S. M) Derryharrif by Bernadette Walsh. N) Ballinaglough by Ann Moran, aged 11. O) Murder at Breaffy by John Walsh & Liam Mulcahy. P) History of Charles Street, Castlebar by Raymond Fallon, aged 12. Photographs; 1) New St.Gerald’s College, Newport Road, Castlebar ( Front Cover ) 2) St.Gerald’s College, Chapel Street, Castlebar 3) Teaching Staff of St.Gerald’s College, Castlebar, 1971. Parish Sport : Gaelic Games, Rugby & Camogie. Castlebar Associations Review : London, Birmingham & Manchester Births, Deaths & Marriages for 1971 are also included. Index of Castlebar Parish Magazine 1972 1. Parish Review of the past twelve months. -

Farhad Uddin Ahmed Professor Louis Brennan Trinity Business School

The Emergence of Born Global Firms: A Least-developed Country Perspective A Dissertation Presented by Farhad Uddin Ahmed Supervised by Professor Louis Brennan to Trinity Business School The University of Dublin (Trinity College Dublin), Ireland in Fulfilment of the Requirements for the Degree of Doctor of Philosophy in Business Studies Trinity Business School The University of Dublin, Trinity College July 2016 STATEMENT OF ORGINALITY I hereby declare that this scholarship is entirely my own work and that it has not been submitted as an exercise for the award of a degree at this or any other University. Signature/name Date Farhad Uddin Ahmed Trinity Business School The University of Dublin (Trinity College Dublin), Ireland ii COPYRIGHT STATEMENT Please note the following terms and conditions: I agree to deposit this dissertation in the University’s open access institutional repository or allow the library to do so on my behalf, subject to Irish Copyright Legislation and Trinity College Library conditions of use and acknowledgement, This dissertation is also protected by copyright and other intellectual property rights retained by the author of this work, The text, findings or any other materials of this dissertation cannot be reproduced, cited and quoted for commercial and non-commercial purpose without prior formal permission obtained from the author. © 2016 – Farhad Uddin Ahmed All rights reserved. iii DEDICATION This amazing and intellectual PhD journey would not have been possible without the unconditional and boundless blessing, love and encouragement of my parents. Therefore, I would like to dedicate this scholarship to my mother, Chashme Akter and in the memory of my late father, Jamal Uddin Ahmed. -

Irish Facts 2010

DID YOU KNOW? By Deirdre McKiernan‐Hetzler December 2010 That the Irish invaded Canada? On May 31, 1866, Gen. John O’Neill, a 25 year-old decorated Civil War veteran led 1,000 volunteers over the border from Buffalo, NY to Fort Erie, Ontario. They were members of the Irish Republican Brotherhood, commonly known as the Fenians, and their immediate goal was to impair or destroy the locks of theWellandCanaland seize the railway facilities in the vicinity. They made it clear their quarrel was with the British, and not with the Canadians, whom they expressed some hope to “liberate.” Similar raids were to occur simultaneously at other points along the border, as a three- pronged attack was envisioned. From the west, Fenians were to cross theGreat LakesatChicagoandDetroit, and from the east, atSt. Albans,VT. Unfortunately for the Fenian cause, neither of these forces materialized, and O’Neill was left on his own. A larger number of volunteers (one source said 6,000) was still in Buffalo, but when O’Neill sent for reinforcements, not only were there no boats to transport them, but a US Revenue Cutter was patrolling the waters, making a crossing impossible. Eventually the federal government offered those stranded inBuffalofree transportation home, on condition that they desist from neutrality violations. Despite victorious skirmishes at Ridgeway andFort Erie, O’Neill was outnumbered and chose to evacuate his troops. Many were captured but later released for lack of evidence. A few were tried, both inCanadaand inCanandaigua,NY, and charged with violating neutrality laws. Canadian trials resulted in some prison sentences, but in Canandaigua, all charges were dismissed. -

Recent Publications – Faculty of Arts, Humanities and Social Sciences

Recent Publications – Faculty of Arts, Humanities and Social Sciences BY MEMBERS OF THE STAFF AND BY RESEARCH STUDENTS WORKING UNDER THEIR SUPERVISION The publications information has been derived from the College’s Research Support System. Every effort has been made to ensure that the information is accurate and complete. Please notify the Research Support Systems Administrator (email: [email protected]) of any errors or omissions which will be corrected in next year’s Calendar. Trinity Business School Barry, Frank, ‘Tariff-jumping foreign direct investment in protectionist-era Ireland’, Economic History Review, 69, 4 (2016), 1285-1308 [F. Barry, L. Barry, A. Menton] Brady, Mairead, ‘The reality of social media data use in companies’, Marco marketing conference, Trinity College Dublin (2016), 1-3 [Zamani Farhoodeh, Mairead Brady] ‘Enabling interactive communications through social media: research from services contexts’, Social media and interactive communication: a service sector reflective on the challenges for practice and theory, eds M. Durkin, A. McCartan, M. Brady, Oxfordshire, Routledge (2016), 1-6 Social media and interactive communication: a service sector reflective on the challenges for practice and theory, eds M. Durkin, A. McCartan, M. Brady, first edition, Oxfordshire, Routledge (2016), 1-87 ‘Irish game based learning conference’, Proceedings of the 6th Irish conference on game- based learning, September 2016, eds P. Felicia, N. Peirce, M. Brady, A. Devitt, Trinity College Dublin (2016), 1-334 ‘Utilising an Assessment for learning (Afl) approach with large student cohorts in higher education settings’, ECER 2016, European conference on educational research, University College Dublin (2016), 1-3 [M. Kearns, A. Devitt, M. Brady] ‘Towards a framework for the evaluation of digital game-based learning at the third level’, Irish game based learning conference, Trinity College Dublin (2016), 1-3 [E. -

![Études Irlandaises, 40-2 | 2015, « La Crise ? Quelle Crise ? » [En Ligne], Mis En Ligne Le 15 Décembre 2017, Consulté Le 23 Septembre 2020](https://docslib.b-cdn.net/cover/2681/%C3%A9tudes-irlandaises-40-2-2015-%C2%AB-la-crise-quelle-crise-%C2%BB-en-ligne-mis-en-ligne-le-15-d%C3%A9cembre-2017-consult%C3%A9-le-23-septembre-2020-6372681.webp)

Études Irlandaises, 40-2 | 2015, « La Crise ? Quelle Crise ? » [En Ligne], Mis En Ligne Le 15 Décembre 2017, Consulté Le 23 Septembre 2020

Études irlandaises 40-2 | 2015 La crise ? Quelle crise ? Martine Pelletier et Valérie Peyronel (dir.) Édition électronique URL : http://journals.openedition.org/etudesirlandaises/4727 DOI : 10.4000/etudesirlandaises.4727 ISSN : 2259-8863 Éditeur Presses universitaires de Caen Édition imprimée Date de publication : 15 décembre 2015 ISBN : 978-2-7535-4366-9 ISSN : 0183-973X Référence électronique Martine Pelletier et Valérie Peyronel (dir.), Études irlandaises, 40-2 | 2015, « La crise ? Quelle crise ? » [En ligne], mis en ligne le 15 décembre 2017, consulté le 23 septembre 2020. URL : http:// journals.openedition.org/etudesirlandaises/4727 ; DOI : https://doi.org/10.4000/etudesirlandaises. 4727 Ce document a été généré automatiquement le 23 septembre 2020. Études irlandaises est mise à disposition selon les termes de la Licence Creative Commons Attribution - Pas d’Utilisation Commerciale - Partage dans les Mêmes Conditions 4.0 International. 1 SOMMAIRE Introduction Une crise, oui, mais quelle crise ? Martine Pelletier et Valérie Peyronel La crise et l'après-crise : enjeux politiques, économiques et sociaux The Irish Economic Crisis: The Expiry of a Development Model? Vanessa Boullet Les entreprises irlandaises : nouveau moteur de la croissance économique nationale au lendemain de la crise ? Anne Groutel Irish Post-crisis Migratory and Demographic Patterns Catherine Piola The Vulnerability of the Northern Ireland Settlement: British Irish Relations, Political Crisis and Brexit Jennifer Todd Educate that You May be Free? Religion and Critical -

March Newsletter Publisher 2013.Pub

IDEAS CLUB ( BENDIGO ) www.inventorvic.com.au The Inventors Association of Australia (Vic) 30 Reids Lane Warranwood Vic 3134 Phone President on 0418538604 Email: [email protected] Thanks to our Patent Attorney Alex Tzanidis Davies Collison Cave 1 Nicholson Street Wed. March 6th Melbourne VIC 3000 Australia 2013 P: 03 9254 2777 F: 03 9254 2770 45 Miller Cres. For his excellent tutorial for our members Mount Waverley E: [email protected] Our February meeting was another a good start with 11 new visitors which is the most at any meeting for approxi‐ cracker of an evening with Alex Tzani‐ dis helping inventors from 6.30pm to mately 5 years and we thank all those 7.20pm in their understanding of pat‐ who came and hope to see you again. ents and other intellectual property. Meetup social media has contributed strongly and all were quite young which begins to fulfill our aim of lowering the average age of the association members without culling those at the top end! Our new audio/visual equipment made a difference to the enjoyment of the eve‐ ning which was setup and tested before hand. The microphone worked extremely well through the speaker and we even had music before starting. All visitors were informed that our pat‐ ent tutorials are free and that if they had any general inventing questions or Videos For wanted to know more about the associa‐ Inventors tion that they could identify the commit‐ tee members by their black badges and GARY HEGEDUS PRODUCTIONS to speak to them. www.ghproductions.com.au Inventor of the Year winner Proud sponsor of the IAA VIC. -

Download (929Kb)

BIBLIOGRAPHY Books Acierno, Louis J., The History of Cardiology, Parthenon Publishing Group: Pearl River, New York, 1994. Barker, Ralph, Verdict on a Lost Flyer: The story of Bill Lancaster and Chubbie Miller, Fontana/Collins: Sydney, 1986. Bevan, Scott, Baule Unes: Australian artists at war, Random House Australia: Sydney, 2004. Encel, Vivien, Australian Genius: 50 great ideas, Atrand: Crows Nest, NSW, 1988. Brabham, Sir Jack, and Nye, D., The Jack Brabham Story, Minidi Chrysalis: Windsor, NSW, 2004. Cottee, Kay, First Lady: A history-making solo voyage around the world, Macmillan: South Melbourne, 1989. Craddock, David A., Feeling the Air: The famous names and colouiful personalities who pioneered Australia's first jlights, D.A. Craddock through Book House at Wild & Woolley: Sydney, 1999. Crawford, Elizabeth, The JïV<Jmen's Suffrage Movement: A riference guide 1866--1928, Roudedge: London, 2001. Dowson, D. ,Taylor, c., Godet, M. ,Berthe, D. (eds), Fluid Film Lubrication Osborne Reynolds Centenary, Elsevier Science: Amste{dam, 1987. Dundy, Elaine, Finch, Bloody Finch, Michael Joseph: London, 1980. 309 GREAT AUSTRALIAN WORLD FIRSTS Dupre, Lonnie, Greenland Expedition: Where ice is born, Northwood Press; Minnetonka, Minnesota, 2000. Eekert, Allan W, The VUJrld of Opals, John Wiley & Sons: New York, 1997. Evans, Colin, A Question of Evidence: The casebook of great forensic controversies, John Wiley & Sons: Hoboken, NJ; 2003. Faulkner,Trader, Peter Finch:A biography,Taplinger Publishing Company: New York, 1979. Freestone, R. and Hanna, B., Florence Taylor's Hats, Halstead Press: Sydney, 2008. Gilltrap, Terry and Maree, Gilltrap's Australian Cars from 1879: A history of cars built in Australia, Golden Press: Sydney, 1981. -

2013 – Outward FDI from Ireland and Its Policy Context by Louis

Columbia FDI Profiles Country profiles of inward and outward foreign direct investment issued by the Vale Columbia Center on Sustainable International Investment February 12, 2013 Editor-in-Chief: Karl P. Sauvant Editor: Padma Mallampally Managing Editor: Maree Newson Outward FDI from Ireland and its policy context by ∗ Louis Brennan and Rakhi Verma Although starting from a very low base and initially insignificant when compared to the growth of Ireland’s inward foreign direct investment (FDI), Ireland’s outward FDI flows have steadily increased over time. In particular, the decade following 2000 saw a rapid rise in outward FDI flows from Ireland, with its stock growing from US$ 28 billion in 2000 to US$ 324 billion in 2011. This reflects the remarkable growth of annual FDI outflows, from US$ 5 billion in 2000 to US$ 27 billion in 2009, the latter representing the highest recorded value. The year 2004 marked Ireland’s emergence as a net direct investor for the first time in its history. With the global financial and economic crisis, Ireland’s outward FDI flows recorded declines in 2010 and 2011 from the record value attained in 2009. Trends and developments Country-level developments Inward FDI (IFDI) has played a crucial role in the rapid economic growth that Ireland has experienced over the past several decades. Since the 1960s, Ireland’s economic model has been based on the promotion of inward FDI and exports. It is now well recognized that the country’s extraordinary economic progress stems from its success in attracting IFDI. Historically, the importance of such investment has dominated the country’s economic and political agenda. -

Little Book of Irish Science

ScienceIreland @scienceirel Science Foundation Ireland would like to thank all the contributors for their assistance in creating this book We also wish to acknowledge OPEN Design & Digital for their work in crafting and illustrating the content. ScienceIreland @scienceirel Science Foundation Ireland would like to thank all the contributors for their assistance in creating this book We also wish to acknowledge OPEN Design & Digital for their work in crafting and illustrating the content. Contents 1 Remote Fetal Care 2 Beehave 3 Marine Sponges 4 Under the Sea 5 The Perfect Pint 6-9 Astronomy 10 Stem Cells 11 Banana vs.Virus 12 SelfSense 13 MRG 14 Magnetism Switch 15-18 Physics 19 The Perfect Foam 20 SurgaColl 21 Speed Gene 22 CONNECT 23 Water Monitoring 24-27 Chemistry 28 Gut Bugs 29 Stress 30 Most Cited 31 Wattics 32 Ireland’s Energy 33-36 Medicine 37 Battery Power 38 Next Generation 39 Women in IT 40 Nanolayers 41 Bowel Cancer Screen 42-45 Space 46 William C. Campbell 47 Mutebutton 48 Marine Wildlife 49 Indoor Ocean 50-53 Nature 54 Obesity 55 Life Through A Lens 56 Brain Freeze 57 Highly Ranked 58 Photonics 59-62 Earth 63 Cattle Breeding 64 Prehistoric Cow 65 Good Vibrations 66 New Weapon 67-71 Mechanics 72 Virtual Sawmill 73 Intel Quark 1000 74 Heart Strings 75 Infant Seizures 76 COMBINE 77-80 Inventors 81 Flying high 82 What You Eat 83 Drones 84 Bat Clues 85 Irish Genetics 86-90 Chemistry 91 Smart Futures 92 ADAPT 93 Stroke 94 MedTech 95 Oxymem 96 Digging Deep 97-100 Technology Acknowledgements SFI Little Book - Internals.indd 1 19/04/2016 10:53 a.m.