UNU-CRIS Working Papers W-2010/4

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

The Rule of Law and Urban Development

The Rule of Law and Urban Development The transformation of Singapore from a struggling, poor country into one of the most affluent nations in the world—within a single generation—has often been touted as an “economic miracle”. The vision and pragmatism shown by its leaders has been key, as has its STUDIES URBAN SYSTEMS notable political stability. What has been less celebrated, however, while being no less critical to Singapore’s urban development, is the country’s application of the rule of law. The rule of law has been fundamental to Singapore’s success. The Rule of Law and Urban Development gives an overview of the role played by the rule of law in Singapore’s urban development over the past 54 years since independence. It covers the key principles that characterise Singapore’s application of the rule of law, and reveals deep insights from several of the country’s eminent urban pioneers, leaders and experts. It also looks at what ongoing and future The Rule of Law and Urban Development The Rule of Law developments may mean for the rule of law in Singapore. The Rule of Law “ Singapore is a nation which is based wholly on the Rule of Law. It is clear and practical laws and the effective observance and enforcement and Urban Development of these laws which provide the foundation for our economic and social development. It is the certainty which an environment based on the Rule of Law generates which gives our people, as well as many MNCs and other foreign investors, the confidence to invest in our physical, industrial as well as social infrastructure. -

Mechanisms to Ensure Compliance

M Womens E C H A N I S M Rights S Mechanisms to ensure compliance Committee membership and selection process The Committee on the Elimination of Discrimination against Women tasked to monitor compliance with the Women’s Convention was established in 1982, it came into force. It consists of 23 members recognised for competence in their fields of specialisation. Al- though nominated and elected by their respective governments, The Committee on the Elimination which should be States parties to the Women’s Convention, the of Discrimination against Women members serve on the Committee as independent experts. The current roster of members logic behind this is the double role of the state as protector and violator of human rights. The expert is therefore best left to work chair Ms. Aída González Martínez Mexico solo, free from his/her government’s suasion. vice-chairs The members are elected by secret ballot from a list of nominees. Ms. Yung-Chung Kim South Korea Each State party is entitled to name one nominee to the list. Ms. Ahoua Ouedraogo Burkina Faso Governments have made a point of nominating women to the Ms. Hanna Beate Schöpp-Schilling Germany Committee; in its nearly 20-year history, only once did the Com- members mittee have a male member. Members serve a four-year term with Ms. Charlotte Abaka Ghana the possibility of re-election. Committee membership is anchored Ms. Ayse Feride Acar Turkey on equitable geographic distribution and regional groups coordi- Ms. Emna Aouij Tunisia nate the nomination to ensure the global character of the Ms. -

Date Published: 11 Mar 2014 Dr Vivian Balaskrishnan, Minister for the Environment and Water Resources, Had Announced in His Comm

Date Published: 11 Mar 2014 Dr Vivian Balaskrishnan, Minister for the Environment and Water Resources, had announced in his Committee of Supply (COS) speech today that the Government of Singapore has decided to appoint an International Advisory Panel on Transboundary Pollution (IAP). 2. The Terms of Reference of the IAP are to study and advise the Government of Singapore on the trends and developments in international law relating to transboundary pollution and on the issues arising under international law from the impact of transboundary pollution as well as on the related solutions and practical steps which Singapore can adopt in light of the foregoing. Deputy Prime Minister (DPM) Mr Teo Chee Hean, who is also Chairman of the Inter-Ministerial Committee on Climate Change and Co-ordinating Minister for National Security, has appointed Professor S. Jayakumar and Professor Tommy Koh to co-chair the IAP, which will comprise legal experts from Singapore and abroad (their bios are attached at Annex A and Annex B respectively). 3. In making the appointment, DPM Teo said that: "The severe haze that enveloped Singapore in 2013 was a grim reminder that countries, especially small ones, are vulnerable to pollution that originates from outside their borders. In order to protect the health of our people, we need to explore all available avenues to tackle such transboundary environmental challenges. The Government has thus decided to set up an International Advisory Panel to study and advise the Government on trends and developments in international law relating to transboundary pollution and the options available to Singapore under international law. -

The National Heritage Board Announces New Board Members

MEDIA RELEASE FOR IMMEDIATE RELEASE FRESH FACES AND DIVERSE BACKGROUNDS: THE NATIONAL HERITAGE BOARD ANNOUNCES NEW BOARD MEMBERS *This supersedes the press release made on 29 October 2009. SINGAPORE, 6 November 2009 – The National Heritage Board is pleased to announce its new main board members with confidence that these fresh faces and new ideas will help Singaporeans of all ages cherish our heritage and museums even more. Tasked to help formulate strategic directions for the organisation, the 24-member NHB board aims to promote public awareness of the arts, culture and heritage and to provide a permanent repository of record of our nation’s history. Members who serve terms of two years, are encouraged to conceive ideas to educate Singaporeans on our heritage. Some notable members joining the main board include funny woman and self-made businesswoman who heads Fly Entertainment, Ms Irene Ang. Best known as the lovable Rosie of the local sitcom Phua Chu Kang, Ms Ang was initially surprised when approached by NHB as a candidate but was persuaded that her unique ability to communicate with heartlanders would be invaluable in helping them nurture a love for heritage. Said Ms Ang, “I hope to use my celebrity status and my Fly Entertainment contacts to support Singapore’s effort to keep our heritage alive. Personally, I enjoy collecting old stuff when I travel and I am very sentimental – I want to show people that the arts and heritage is not as “atas” (high-brow) as many think.” Her love for museums stems from her passion for the history lessons of her school days. -

Dr. Kevin Hr Villanueva

DR. KEVIN HR VILLANUEVA Nationality : Filipino and Spanish International Mobile: +37 281 502 590 Philippine Mobile : +63 9165958191 E-mail: [email protected] / [email protected] Academic Expertise and Public Engagement : My areas of expertise and public engagement have been on the international human rights regime and processes of ASEAN regional integration. The theoretical thrust of my work comes from constructivism in IR and the power of institutions in the English School tradition. In 2012, I was a member of the Philippine Delegation in the drafting of the ASEAN Human Rights Delegation and I continue to work on several projects with the Philippine Department of Foreign Affairs. This experience interweaves with interest on the communicative dynamics of diplomatic negotiations through the analytical lens of sociology and linguistics. Recent interests have brought me to studying humanitarianism in the development of regional mechanisms (East Asia/ASEAN) on disaster management and search and rescue. In the context of K+12 National Curricular Reform, I participate in key committees at the University of the Philippines both in terms of policy formulation and substantive course content design, monitoring and evaluation. I am a USAID -Stride Independent Expert for the Philippine Commission on Higher Education (CHED). EDUCATION UNIVERSITY OF LEEDS PhD in INTERNATIONAL POLITICS (2010 – 8th September 2014) University Research Scholarship Doctoral Thesis nominated to the BISA - British International Studies Association 2015 Michael Nicholson -

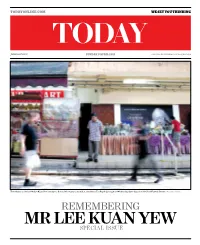

Lee Kuan Yew Continue to flow As Life Returns to Normal at a Market at Toa Payoh Lorong 8 on Wednesday, Three Days After the State Funeral Service

TODAYONLINE.COM WE SET YOU THINKING SUNDAY, 5 APRIL 2015 SPECIAL EDITION MCI (P) 088/09/2014 The tributes to the late Mr Lee Kuan Yew continue to flow as life returns to normal at a market at Toa Payoh Lorong 8 on Wednesday, three days after the State Funeral Service. PHOTO: WEE TECK HIAN REMEMBERING MR LEE KUAN YEW SPECIAL ISSUE 2 REMEMBERING LEE KUAN YEW Tribute cards for the late Mr Lee Kuan Yew by the PCF Sparkletots Preschool (Bukit Gombak Branch) teachers and students displayed at the Chua Chu Kang tribute centre. PHOTO: KOH MUI FONG COMMENTARY Where does Singapore go from here? died a few hours earlier, he said: “I am for some, more bearable. Servicemen the funeral of a loved one can tell you, CARL SKADIAN grieved beyond words at the passing of and other volunteers went about their the hardest part comes next, when the DEPUTY EDITOR Mr Lee Kuan Yew. I know that we all duties quietly, eiciently, even as oi- frenzy of activity that has kept the mind feel the same way.” cials worked to revise plans that had busy is over. I think the Prime Minister expected to be adjusted after their irst contact Alone, without the necessary and his past week, things have been, many Singaporeans to mourn the loss, with a grieving nation. fortifying distractions of a period of T how shall we say … diferent but even he must have been surprised Last Sunday, about 100,000 people mourning in the company of others, in Singapore. by just how many did. -

International Law Asian Journal Of

THE JOURNAL OF THE ASIAN SOCIETY OF INTERNATIONAL LAW VOLUME 2 ISSUE 2 JULY 2012 ISSN 2044-2513 Asian Journal of International Law Downloaded from https://www.cambridge.org/core. IP address: 170.106.202.126, on 01 Oct 2021 at 15:17:41, subject to the Cambridge Core terms of use, available at https://www.cambridge.org/core/terms. https://doi.org/10.1017/S2044251312000161 Asian Journal of International Law The Asian Journal of International Law is the journal of the Asian Society of International Law. It publishes peer-reviewed scholarly articles and book reviews on public and private international law. The regional focus of the journal is broadly conceived. Some articles may focus specifically on Asian issues; others will bring one of the many Asian perspectives to bear on issues of global concern. Still others will be of more general interest to scholars, practitioners, and policy-makers located in or working on Asia. The journal is published in English as a matter of practical convenience rather than political endorsement. English language reviews of books in other languages are particularly welcomed. The journal is produced for the Asian Society of International Law by the National University of Singapore Faculty of Law and succeeds the Singapore Year Book of International Law. For further information, forthcoming pieces, and guidelines on how to submit articles or book reviews, please visit www.AsianJIL.org. instructions for contributors The Asian Journal of International Law welcomes unsolicited articles and proposals for book reviews. For details, visit www.AsianJIL.org. © Asian Journal of International Law ISSN 2044-2513 E-ISSN 2044-2521 This journal issue has been printed on FSC-certified paper and cover board. -

Asian Studies 2021

World Scientific Connecting Great Minds ASIAN STUDIES 2021 AVAILABLE IN PRINT AND DIGITAL MORE DIGITAL PRODUCTS ON WORLDSCINET HighlightsHighlights Asian Studies Catalogue 2021 page 5 page 6 page 6 page 7 Editor-in-Chief: Kym Anderson edited by Bambang Susantono, edited by Kai Hong Phua Editor-in-Chief: Mark Beeson (University of Adelaide and Australian Donghyun Park & Shu Tian (Lee Kuan Yew School of Public Policy, (University of Western National University, Australia) (Asian Development Bank, Philippines) National University of Singapore), et al. Australia, Australia) page 9 page 14 page 14 page 14 by Tommy Koh by Cuihong Cai by Victor Fung-Shuen Sit by Sui Yao (Ambassador-at-Large, (Fudan University, China) (University of Hong Kong, (Central University of Finance Singapore) & Lay Hwee Yeo Hong Kong) and Economics, China) (European Union Centre, Singapore) page 18 page 19 page 19 page 20 by Jinghao Zhou edited by Zuraidah Ibrahim by Alfredo Toro Hardy by Yadong Luo (Hobart and William Smith & Jeffie Lam (South China (Venezuelan Scholar (University of Miami, USA) Colleges, USA) Morning Post, Hong Kong) and Diplomat) page 26 page 29 page 32 page 32 by Cheng Li by & by Gungwu Wang edited by Kerry Brown Stephan Feuchtwang (Brookings Institution, USA) (National University of (King’s College London, UK) Hans Steinmüller (London Singapore, Singapore) School of Economics, UK) About World Scientific Publishing World Scientific Publishing is a leading independent publisher of books and journals for the scholarly, research, professional and educational communities. The company publishes about 600 books annually and over 140 journals in various fields. World Scientific collaborates with prestigious organisations like the Nobel Foundation & US ASIA PACIFIC ..................................... -

Valedictory Reference in Honour of Justice Chao Hick Tin 27 September 2017 Address by the Honourable the Chief Justice Sundaresh Menon

VALEDICTORY REFERENCE IN HONOUR OF JUSTICE CHAO HICK TIN 27 SEPTEMBER 2017 ADDRESS BY THE HONOURABLE THE CHIEF JUSTICE SUNDARESH MENON -------------------------------------------------------------------------------------------------------- Chief Justice Sundaresh Menon Deputy Prime Minister Teo, Minister Shanmugam, Prof Jayakumar, Mr Attorney, Mr Vijayendran, Mr Hoong, Ladies and Gentlemen, 1. Welcome to this Valedictory Reference for Justice Chao Hick Tin. The Reference is a formal sitting of the full bench of the Supreme Court to mark an event of special significance. In Singapore, it is customarily done to welcome a new Chief Justice. For many years we have not observed the tradition of having a Reference to salute a colleague leaving the Bench. Indeed, the last such Reference I can recall was the one for Chief Justice Wee Chong Jin, which happened on this very day, the 27th day of September, exactly 27 years ago. In that sense, this is an unusual event and hence I thought I would begin the proceedings by saying something about why we thought it would be appropriate to convene a Reference on this occasion. The answer begins with the unique character of the man we have gathered to honour. 1 2. Much can and will be said about this in the course of the next hour or so, but I would like to narrate a story that took place a little over a year ago. It was on the occasion of the annual dinner between members of the Judiciary and the Forum of Senior Counsel. Mr Chelva Rajah SC was seated next to me and we were discussing the recently established Judicial College and its aspiration to provide, among other things, induction and continuing training for Judges. -

Academic Years 2001-2002

Department of Medicine ANNUAL REPORT — A CADEMIC YEARS 2001-2002 Patient Care, Teaching & Department of Medicine RHODE ISLAND HOSPITAL/HASBRO CHILDREN’S HOSPITAL THE MIRIAM HOSPITAL Research MEMORIAL HOSPITAL OF RHODE ISLAND WOMEN & INFANT’S HOSPITAL VETERAN’S ADMINISTRATION MEDICAL CENTER Rhode Island Hospital/Hasbro Children’s Hospital The Miriam Hospital Department of Medicine Memorial Hospital of Rhode Island Administrative Offices Women & Infant’s Hospital Rhode Island Hospital Veteran’s Administration Medical Center Main Building, 1st Floor 593 Eddy Street Providence, RI 02903 OF MEDICINEDEPARTMENT – ANNUAL REPORT – ACADEMIC YEARS 2001-2002 WWW.BROWNMEDICINE.ORG On the Brown campus are plays, concerts, The Department of Medicine’s 2001-2002 Brown University, Providence, Annual Report was produced by: movies, lectures, art exhibits and many other - ’ and New England sources of entertainment and intellectual Designer: stimulation throughout the year. A modern rown University, Providence and athletic complex within easy walking distance Rhode Island together provide a from the main campus offers swimming in a pleasant and interesting setting for Printing: modern Olympic-sized pool, extensive study, recreation, and daily life. exercise equipment, squash and tennis courts, BFrom atop College Hill the University and ice-skating, as well as playing fields and overlooks downtown Providence, the capital of Photography: facilities for intramural and varsity team Rhode Island and the second largest city in sports , New England. The University was founded in 1764; its architecturally diverse buildings and ’ quadrangles center on the original College Rhode Island is especially known for Copy Edit and Proofing: Green. In the surrounding residential area are recreational opportunities centered on the many houses that date back to colonial times, ocean and Narragansett bay, including together with various historic sites, including boating, fishing, sailing and swimming. -

Report of the Committee on the Elimination of Discrimination Against Women

A/75/38 United Nations Report of the Committee on the Elimination of Discrimination against Women Seventy-third session (1–19 July 2019) Seventy-fourth session (21 October–8 November 2019) Seventy-fifth session (10–28 February 2020) General Assembly Official Records Seventy-fifth Session Supplement No. 38 A/75/38 General Assembly A/75/38 Official Records Seventy-fifth Session Supplement No. 38 Report of the Committee on the Elimination of Discrimination against Women Seventy-third session (1–19 July 2019) Seventy-fourth session (21 October–8 November 2019) Seventy-fifth session (10–28 February 2020) United Nations • New York, 2020 Note Symbols of United Nations documents are composed of letters combined with figures. Mention of such a symbol indicates a reference to a United Nations document. ISSN 0255-0970 Contents Chapter Page Letter of transmittal ............................................................. 6 Part One Report of the Committee on the Elimination of Discrimination against Women on its seventy-third session ........................................................... 7 I. Decisions adopted by the Committee ............................................... 8 II. Organizational and other matters .................................................. 10 A. States parties to the Convention and to the Optional Protocol ....................... 10 B. Opening of the session ...................................................... 10 C. Adoption of the agenda ...................................................... 10 D. Report of the pre-sessional -

Enrique A. Manalo Acting Secretary of Foreign Affairs

Enrique A. Manalo Acting Secretary of Foreign Affairs Seasoned career diplomat Undersecretary Enrique Manalo is currently the Acting Secretary of Foreign Affairs. Undersecretary Manalo has been at the forefront in addressing several critical issues on foreign policy. His career in the Philippine Foreign Service spans nearly four decades since he joined the Department in 1979. Despite being the son of two well-respected diplomats, Usec. Manalo has carved out a name for himself in the world of diplomacy and foreign affairs. Usec. Manalo is the son of the late Ambassador Armando Manalo, a journalist and the former Philippine Ambassador to Belgium and political adviser of the Philippine Mission to the United Nations. His mother is Ambassador Rosario Manalo, the first female career diplomat of the Department of Foreign Affairs who was recently elected by acclamation as the Rapporteur of the 23-member Committee of Experts of the United Nations Convention on the Elimination of All Forms of Discrimination Against Women (CEDAW). He is currently the DFA’s Undersecretary for Policy, his second stint in the same position since first taking on the challenge as Foreign Affairs Undersecretary for Policy for three years from 2007 to 2010. He has represented the Philippines and has served as the chairman of various international meetings and conferences, the latest of which is the Senior Officials Meeting during the ASEAN Foreign Ministers Meeting Retreat (AMM Retreat) in Boracay, Malay, Aklan, last February 20. Before his appointment as the Undersecretary for Policy, Usec. Manalo previously served as the Philippine Ambassador to the United Kingdom from 2011 to 2016; Non-Resident Philippine Ambassador to Ireland from 2013 to 2016; Philippine Ambassador to Belgium and Luxembourg, and Head of the Philippine Mission to the European Union from 2010 to 2011; and Philippine Ambassador and Permanent Representative to the Philippine Mission to the United Nations and Other International Organizations in Geneva, Switzerland from 2003 to 2007.