Arxiv:1812.01365V1 [Physics.Flu-Dyn] 4 Dec 2018

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Moremore Millikan’S Oil-Drop Experiment

MoreMore Millikan’s Oil-Drop Experiment Millikan’s measurement of the charge on the electron is one of the few truly crucial experiments in physics and, at the same time, one whose simple directness serves as a standard against which to compare others. Figure 3-4 shows a sketch of Millikan’s apparatus. With no electric field, the downward force on an oil drop is mg and the upward force is bv. The equation of motion is dv mg Ϫ bv ϭ m 3-10 dt where b is given by Stokes’ law: b ϭ 6a 3-11 and where is the coefficient of viscosity of the fluid (air) and a is the radius of the drop. The terminal velocity of the falling drop vf is Atomizer (+) (–) Light source (–) (+) Telescope Fig. 3-4 Schematic diagram of the Millikan oil-drop apparatus. The drops are sprayed from the atomizer and pick up a static charge, a few falling through the hole in the top plate. Their fall due to gravity and their rise due to the electric field between the capacitor plates can be observed with the telescope. From measurements of the rise and fall times, the electric charge on a drop can be calculated. The charge on a drop could be changed by exposure to x rays from a source (not shown) mounted opposite the light source. (Continued) 12 More mg Buoyant force bv v ϭ 3-12 f b (see Figure 3-5). When an electric field Ᏹ is applied, the upward motion of a charge Droplet e qn is given by dv Weight mg q Ᏹ Ϫ mg Ϫ bv ϭ m n dt Fig. -

Settling Velocities of Particulate Systems†

Settling Velocities of Particulate Systems† F. Concha Department of Metallurgical Engineering University of Concepción.1 Abstract This paper presents a review of the process of sedimentation of individual particles and suspensions of particles. Using the solutions of the Navier-Stokes equation with boundary layer approximation, explicit functions for the drag coefficient and settling velocities of spheres, isometric particles and arbitrary particles are developed. Keywords: sedimentation, particulate systems, fluid dynamics Discrete sedimentation has been successful to 1. Introduction establish constitutive equations in processes using Sedimentation is the settling of a particle, or sus- sedimentation. It establishes the sedimentation prop- pension of particles, in a fluid due to the effect of an erties of a certain particulate material in a given fluid. external force such as gravity, centrifugal force or Nevertheless, to analyze a sedimentation process and any other body force. For many years, workers in to obtain behavioral pattern permitting the prediction the field of Particle Technology have been looking of capacities and equipment design procedures, an- for a simple equation relating the settling velocity of other approach is required, the so-called continuum particles to their size, shape and concentration. Such approach. a simple objective has required a formidable effort The physics underlying sedimentation, that is, the and it has been solved only in part through the work settling of a particle in a fluid is known since a long of Newton (1687) and Stokes (1844) of flow around time. Stokes presented the equation describing the a particle, and the more recent research of Lapple sedimentation of a sphere in 1851 and that can be (1940), Heywood (1962), Brenner (1964), Batchelor considered as the starting point of all discussions of (1967), Zenz (1966), Barnea and Mitzrahi (1973) the sedimentation process. -

Gravity and Projectile Motion

Do Now: What is gravity? Gravity Gravity is a force that acts between any 2 masses. Two factors affect the gravitational attraction between objects: mass and distance. What direction is Gravity? Earth’s gravity acts downward toward the center of the Earth. What is the difference between Mass and Weight? • Mass is a measure of the amount of matter (stuff) in an object. • Weight is a measure of the force of gravity on an object. • Your mass never changes,no matter where you are in the universe. But your weight will vary depending upon the force of gravity pulling down on you. Would you be heavier or lighter on the Moon? Gravity is a Law of Science • Newton realized that gravity acts everywhere in the universe, not just on Earth. • It is the force that makes an apple fall to the ground. • It is the force that keeps the moon orbiting around Earth. • It is the force that keeps all the planets in our solar system orbiting around the sun. What Newton realized is now called the Law of Universal Gravitation • The law of universal gravitation states that the force of gravity acts between all objects in the universe. • This means that any two objects in the universe, without exception, attract each other. • You are attracted not only to Earth but also to all the other objects around you. A cool thing about gravity is that it also acts through objects. Free Fall • When the only force acting on an object is gravity, the object is said to be in free fall. -

Terminal Velocity and Projectiles Acceleration Due to Gravity

Terminal Velocity and Projectiles To know what terminal velocity is and how it occurs To know how the vertical and horizontal motion of a projectile are connected Acceleration Due To Gravity An object that falls freely will accelerate towards the Earth because of the force of gravity acting on it. The size of this acceleration does not depend mass, so a feather and a bowling ball accelerate at the same rate. On the Moon they hit the ground at the same time, on Earth the resistance of the air slows the feather more than the bowling ball. The size of the gravitational field affects the magnitude of the acceleration. Near the surface of the Earth the gravitational field strength is 9.81 N/kg. This is also the acceleration a free falling object would have on Earth. In the equations of motion a = g = 9.81 m/s. Mass is a property that tells us how much matter it is made of. Mass is measured in kilograms, kg Weight is a force caused by gravity acting on a mass: weight = mass x gravitational field strength w mg Weight is measured in Newtons, N Terminal Velocity If an object is pushed out of a plane it will accelerate towards the ground because of its weight (due to the Earth’s gravity). Its velocity will increase as it falls but as it does, so does the drag forces acting on the object (air resistance). Eventually the air resistance will balance the weight of the object. This means there will be no overall force which means there will be no acceleration. -

Terminal Velocity

Terminal Velocity D. Crowley, 2008 2018年10月23日 Terminal Velocity ◼ To understand terminal velocity Terminal Velocity ◼ What are the forces on a skydiver? How do these forces change (think about when they first jump out; during free fall; and when the parachute has opened)? ◼ What happens if the skydiver changes their position? ◼ The skydiver’s force (Fweight=mg) remains the same throughout the jump ◼ But their air resistance changes depending upon what they’re doing which changes the overall resultant force Two Most Common Factors that Affect Air Resistance ◼Speed of the Object ◼Surface Area Air Resistance ◼ More massive objects fall faster than less massive objects Since the 150-kg skydiver weighs more (experiences a greater force of gravity), it will accelerate to higher speeds before reaching a terminal velocity. Thus, more massive objects fall faster than less massive objects because they are acted upon by a larger force of gravity; for this reason, they accelerate to higher speeds until the air resistance force equals the gravity force. Skydiving ◼ Falling objects are subject to the force of gravity pulling them down – this can be calculated by W=mg Weight (N) = mass (kg) x gravity (N/kg) ◼ On Earth the strength of gravity = 9.8N/kg ◼ On the Moon the strength of gravity is just 1.6N/kg Positional ◼ What happens when you change position during free-fall? ◼ Changing position whilst skydiving causes massive changes in air resistance, dramatically affecting how fast you fall… Skydiving Stages ◼ Draw the skydiving stages ◼ Label the forces -

Viscosity Measurement Using Optical Tracking of Free Fall in Newtonian Fluid N

Vol. 128 (2015) ACTA PHYSICA POLONICA A No. 1 Viscosity Measurement Using Optical Tracking of Free Fall in Newtonian Fluid N. Kheloufia;b;* and M. Lounisb;c aLaboratoire de Géodésie Spatiale, Centre des Techniques Spatiales, BP 13 rue de Palestine Arzew 31200 Oran, Algeria bLaboratoire LAAR Faculté de Physique, Département de Technologie des Materiaux, Université des Sciences et de la Technologie d'Oran USTO-MB, BP 1505, El M'Naouer 31000 Oran, Algeria cFaculté des Sciences et de la Technologie, Université de Khemis Miliana UKM, Route de Theniet El Had 44225 Khemis Miliana, Algeria (Received July 1, 2014; revised version April 6, 2015; in nal form May 6, 2015) This paper presents a novel method in viscosity assessment using a tracking of the ball moving in Newtonian uid. The movement of the ball is assimilated to a free fall within a tube containing liquid of whose we want to measure a viscosity. In classical measurement, height of fall is estimated directly by footage where accuracy is not really considered. Falling ball viscometers have shown, on the one hand, a limit in the ball falling height measuring, on the other hand, a limit in the accuracy estimation of velocity and therefore a weak precision on the viscosity calculation of the uids. Our technique consist to measure the fall height by taking video sequences of the ball during its fall and thus estimate its terminal velocity which is an important parameter for cinematic velocity computing, using the Stokes formalism. The time of fall is estimated by cumulating time laps between successive video sequences which mean that we can nally estimate the cinematic viscosity of the studied uid. -

P3 3 a Penny for Your Thoughts

Journal of Physics Special Topics An undergraduate physics journal P3 3 A Penny For Your Thoughts S.Lovett, H. Conners, P. Patel, C. Wilcox Department of Physics and Astronomy, University of Leicester, Leicester, LE1 7RH December 13, 2018 Abstract In this paper we have discussed how much more massive the Earth would be and how the mass of a penny would change so that if it were dropped from the top of the Empire State building it could kill a passer-by below. We found that in order to be true the Earth would have to have a mass of 4.93×1028 kg and the penny would have terminal velocity of 172.8 ms-1 . Introduction It is a commonly believed myth that if a penny F = mvT =t (1) was dropped from the highest point of the Em- pire State building it could kill a person it made Where F is the force exerted by the coin in contact with at the base. This fact has been N, m is the mass of the coin in kg, vT is the proven false in other literature [1]. The velocity terminal velocity of the coin and t is the contact of the penny is reduced significantly due to drag, time between the penny and the persons head. -1 meaning the force it exerts on impact is far below We use vT= 11 ms and m = 2.5 g, the mass what would be required to kill someone [1]. How- of a US penny [3]. We assume that the impact ever, if the Earth was more massive the penny is similar to that of a hard ball hitting a solid would feel a greater force due to gravity and its floor thus giving a contact time of t= 6ms [4]. -

Coffee Filter Lab As Objects Fall, They Increase Their Speed Due to the Downward Pull of Gravity

Coffee Filter Lab As objects fall, they increase their speed due to the downward pull of gravity. Air resistance counteracts gravity's pull by resisting the downward motion of the object. The amount of air resistance depends upon a variety of factors, most noticeably, the object's speed. As objects move faster, they encounter more air resistance. When the amount of upward air resistance force is equal to the downward Figure 1 gravity force, the object encounters a balance of forces and is said to have reached a terminal velocity. The terminal velocity value is the final, constant velocity value achieved by the falling object. A group of physics students are investigating the terminal velocity values obtained by falling coffee filters. They videotape the falling filters and use video analysis software to analyze the motion. The video is imported into the software program and the filter's position in each consecutive frame is clicked on (see Figure 1). The software uses the position coordinates to generate a plot of the vertical velocity as a function of time. Figure 2 shows the velocity versus time graph that resulted from the Figure 2: Velocity vs. Time - Single Filter analysis of the motion of a single filter. The lab group then investigated the effect of mass on the motion of the falling filters. They stacked varying numbers of pleated coffee filters tightly together and analyzed the motion of the stacks of filters. They determined the terminal velocity of the stacks of filters. The students also measured the mass of the filters to determine their weight and used the value to determine the amount of air resistance encountered by the filters. -

Question Answers Solution This Problem Corresponds to METSPE2 Problem

PPI Learning Hub Admin : Questions https://learn.ppi2pass.com/admin/questions/0/preview/25159 QUESTION DATA Question Vendor A 3 in diameter steel sphere achieves a terminal velocity of 122 in/sec when dropping through 0000004727 a tall column of liquid. The density of the liquid is 87 lbm/ft3 . The density of steel is 488 lbm/ft 3 . Solving Time The final drag coefficient of the sphere is most nearly Difficulty Answers easy (A) 0.22 Quantitative? Yes (B) 0.34 Status (C) 0.40 Archived Created On (D) 0.48 02/12/2018 10:12:43 PM The answer is (D). Published On 02/12/2018 10:12:43 Solution PM Content in blue refers to the NCEES Handbook. Modified On 05/12/2020 05:10:01 When buoyancy effects are taken into account, an object falling through a fluid under its own PM weight will reach a terminal velocity (settling velocity) if the net force acting on the object OTHER VERSIONS becomes zero. When the terminal velocity is reached, the weight of the object, W, is exactly balanced by the upward buoyancy force, Fbuoyant, and the drag force, FD. 05/18/2020 04:59:17 PM (Active) (/admin /questions If the falling object is spherical in shape, the three forces are as follows. v is the terminal t /preview/49804) velocity. πD 3 /6 is the volume of a sphere, and πD 2 /4 is the projected area of the sphere in the direction of flow. [Mensuration of Areas and Volumes: Nomenclature] DISCIPLINES Density, Specific Weight, and Specific Gravity FE Chemical (/admin /questions /index?sfield=discipline& stext=FE Chemical) Archimedes’ Principle and Buoyancy FE Mechanical -

What Is Terminal Velocity? How Do We Find It?

Flipping Physics Lecture Notes: What is Terminal Velocity? How Do We Find It? http://www.flippingphysics.com/terminal-velocity.html If we drop an object in the vacuum you can breathe, the object is in free fall. However, the reality is that air exists, and the object will not be in free fall. Let’s draw a free body diagram on an object after it is released, at rest, in the air. We can sum the forces on the object in the y-direction: And we can solve for the acceleration of the object: In other words, in the absence of air resistance, the object is in free fall. When the object is first dropped, the velocity of the object is zero, therefore the force of drag acting on the object equals zero. At that initial point: As time goes by, the velocity of the object increases in magnitude, causing the force of drag to increase in magnitude, causing the acceleration of the object to get closer and closer to zero. When the force of drag has increased to the point where it is equal in magnitude to the force of gravity, the acceleration of the object equals zero; the velocity of the object is now constant. This constant velocity is called the terminal velocity of the object, vt. (Not to be confused with the tangential velocity of an object which is also vt.) We can solve for the terminal velocity of the object by setting the acceleration of the object in the y-direction equal to zero. Please do not memorize this equation! Instead, understand how to derive it. -

Settling & Sedimentation in Particle- Fluid Separation

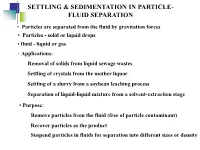

SETTLING & SEDIMENTATION IN PARTICLE- FLUID SEPARATION • Particles are separated from the fluid by gravitation forces • Particles - solid or liquid drops • fluid - liquid or gas • Applications: Removal of solids from liquid sewage wastes Settling of crystals from the mother liquor Settling of a slurry from a soybean leaching process Separation of liquid-liquid mixture from a solvent-extraction stage • Purpose: Remove particles from the fluid (free of particle contaminant) Recover particles as the product Suspend particles in fluids for separation into different sizes or density MOTION OF PARTICLES THROUGH FLUID Three forces acting on a rigid particle moving in a fluid : Drag force Buoyant force External force 1. external force, gravitational or centrifugal 2. buoyant force, which acts parallel with the external force but in the opposite direction 3. drag force, which appears whenever there is relative motion between the particle and the fluid (frictional resistance) Drag: the force in the direction of flow exerted by the fluid on the solid Terminal velocity, ut Drag force Buoyant force External force, gravity The terminal velocity of a falling object is the velocity of the object when the sum of the drag force (Fd) and buoyancy equals the downward force of gravity (FG) acting on the object. Since the net force on the object is zero, the object has zero acceleration. In fluid dynamics, an object is moving at its terminal velocity if its speed is constant due to the restraining force exerted by the fluid through which it is moving. Terminal velocity, ut The terminal velocity of a falling body occurs during free fall when a falling body experiences zero acceleration. -

Motion in Fluids

1 Motion in fluids Introduction In swimming bacteria or diffusing proteins, viscous rather than inertial forces dominate the dynamics of motion. A common measure of the ratio of the inertial to viscous forces is known as the Reynolds number: ρ`v R = (1) e η Where ρ is the fluid density, v is the velocity of the object, ` is a characteristic length of the object, and η is the fluid viscosity. Our everyday experience is mostly with high Reynolds number environments where inertial forces dominate. Swimming, for example, is a high Reynolds number activity. We propel ourselves through the water by accelerating the fluid behind us; the inertial force from a single stroke lets us glide meters before we come to a stop. Low Reynolds number activities are less common, but stirring a jar of honey with a spoon is one example. It is the viscosity of the honey and not the mass of the honey that makes the stirring difficult. When you let go of the spoon, does it continue to swirl around the jar? No, the spoon stops moving fairly quickly. The viscous force dominates the inertial force. Swimming can be a low Reynolds number activity when the length scale of the swimmer is small. Microorganisms fit this category. A bacterium such as E. coli, is about one micron (10−6 meters) in diameter and travels around 20µm per second, so swimming bacteria have a Reynolds number much less than one and the viscous forces dominate inertial forces. To us, this is a very alien hydrodynamic world. For you to swim at an equivalent Reynolds number, you would need to "swim" in something viscous like honey, at speeds of about a foot a day, while cycling our arms at about 1 stroke per hour.