Nomans, the Navy, and National Security

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Oak Diversity and Ecology on the Island of Martha's Vineyard

Oak Diversity and Ecology on the Island of Martha’s Vineyard Timothy M. Boland, Executive Director, The Polly Hill Arboretum, West Tisbury, MA 02575 USA Martha’s Vineyard is many things: a place of magical beauty, a historical landscape, an environmental habitat, a summer vacation spot, a year-round home. The island has witnessed wide-scale deforestation several times since its settlement by Europeans in 1602; yet, remarkably, existing habitats rich in biodiversity speak to the resiliency of nature. In fact, despite repeated disturbances, both anthropogenic and natural (hurricanes and fire), the island supports the rarest ecosystem (sand plain) found in Massachusetts (Barbour, H., Simmons, T, Swain, P, and Woolsey, H. 1998). In particular, the scrub oak (Quercus ilicifolia Wangenh.) dominates frost bottoms and outwash plains sustaining globally rare lepidopteron species, and formerly supported the existence of an extinct ground-dwelling bird, a lesson for future generations on the importance of habitat preservation. European Settlement and Early Land Transformation In 1602 the British merchant sailor Bartholomew Gosnold arrived in North America having made the six-week boat journey from Falmouth, England. Landing on the nearby mainland the crew found abundant codfish and Gosnold named the land Cape Cod. Further exploration of the chain of nearby islands immediately southwest of Cape Cod included a brief stopover on Cuttyhunk Island, also named by Gosnold. The principle mission was to map and explore the region and it included a dedicated effort to procure the roots of sassafras (Sassafras albidum (Nutt.) Nees) which were believed at the time to be medicinally valuable (Banks, 1917). -

17 Кораблебудування №4 Features of the Current

КОРАБЛЕБУДУВАННЯ № 4 n 2016 DOI 10.15589/jnn20160403 УДК 797.14(100)+629.524.4 Є78 FEATURES OF THE CURRENT STATE OF wORLD yACHTING ОСОБЛИВОСТІ СУЧАСНОГО СТАНУ СВІТОВОГО ЯХТИНГА Svitlana H. yeroshkina С. Г. Єрошкіна, [email protected] асп. ORCID: 0000-0001-7571-4807 National University «Odessa Maritime Academy», Odessa Національний Університет «Одеська Морська Академія», м. Одеса Abstract. The tendencies of the processes that took place in the yachting world (sailing) and its influence on the mod- ern world yachting in general are researched. The evaluation of the current state of world yachting as sailing sport is made. Keywords: yachting; modern composition of yachting; yachting racing. Анотація. Досліджено тенденції процесів, що відбувалися у світовому яхтингу (яхтовому спорту) та його вплив на світовий сучасний яхтинг у цілому. Надано оцінку сучасного стану світового яхтингу як вітрильного спорту. Ключові слова: яхтинг, сучасний склад яхтинга, вітрильний спорт. Аннотация. Исследованы тенденции процессов, которые происходили в мировом яхтинге (парусном спорте) и его влияние на мировой современный яхтинг в целом. Дана оценка современного состояния мирового ях- тинга как парусного спорта. Ключевые слова: яхтинг, современный состав яхтинга, парусный спорт. REFERENCES [1] Glovatskiy V. Uvlekatelnyy mir parusov [Fascinating world of sails]. Moscow, Progress Publ., 1981. Mode of access: http://royallib.com/read/glovatskiy_volodzimeg/uvlekatelniy_mir_parusov.html#0. [2] Katera i yakhty [Boats and yachts]. Mode of access: http://katera.ru/. [3] Leontiev Ye. P. Shkola yachtennogo kapitana [Yacht captain school]. Moscow, Fizkultura i sport Publ., 1983. [4] Clipper. Round the world. Mode of access: https://www.clipperroundtheworld.com/about/about-the-race. [5] Americas Cup. Mode of access: https://www.americascup.com. -

Bulletin of the Massachusetts Archaeological Society, Vol. 62, No. 2 Massachusetts Archaeological Society

Bridgewater State University Virtual Commons - Bridgewater State University Bulletin of the Massachusetts Archaeological Journals and Campus Publications Society Fall 2001 Bulletin of the Massachusetts Archaeological Society, Vol. 62, No. 2 Massachusetts Archaeological Society Follow this and additional works at: http://vc.bridgew.edu/bmas Part of the Archaeological Anthropology Commons Copyright © 2001 Massachusetts Archaeological Society This item is available as part of Virtual Commons, the open-access institutional repository of Bridgewater State University, Bridgewater, Massachusetts. BULLETIN OF THE MASSACHUSElTS ARCHAEOLOGICAL SOCIETY VOLUME 62(2) FALL 2001 CONTENTS: In Memoriam: Great Moose (Russell Herbert Gardner) . Mark Choquet 34 A Tribute to Russell H. Gardner (Great Moose) . Kathryn Fairbanks 39 Reminiscences of Russell H. Gardner (Great Moose) Bernard A. Otto 41 The Many-Storied Danson Stone of Middleborough, Massachusetts Russell H. Gardner (Great Moose) 44 Discovery and Rediscovery of a Remnant 17th Century Narragansett Burial Ground' in Warwick, Rhode Island Alan Leveillee 46 On the Shore of a Pleistocene Lake: the Wamsutta Site (I9-NF-70) Jim Chandler 52 The Blue Heron Site, Marshfield, Massachusetts (l9-PL-847) . John MacIntyre 63 A Fertility Symbol from Cuttyhunk Island, Massachusetts . Ethel Twichell 68 Contributors 33 Editor's Note 33 THE MASSACHUSETTS ARCHAEOLOGICAL SOCIETY, Inc. P.O.Box 700, Middleborough, Massachusetts 02346 MASSACHUSETTS ARCHAEOLOGICAL SOCIETY Officers: Ronald Dalton, 100 Brookhaven Dr., Attleboro, MA 02703 President Donald Gammons, 7 Virginia Dr., Lakeville, MA 02347 Vice President Wilford H. Couts Jr., 127 Washburn Street, Northborough, MA 01532 Clerk Edwin C. Ballard, 26 Heritage Rd., Rehoboth, MA 02769 .. Treasurer Eugene Winter, 54 Trull Ln., Lowell, MA 01852 Museum Coordinator Shirley Blancke, 579 Annursnac Hill Rd., Concord, MA 01742 Bulletin Editor Curtiss Hoffman, 58 Hilldale Rd., Ashland, MA 01721 .................. -

Rapid Formation and Degradation of Barrier Spits in Areas with Low Rates of Littoral Drift*

Marine Geology, 49 (1982) 257-278 257 Elsevier Scientific Publishing Company, Amsterdam- Printed in The Netherlands RAPID FORMATION AND DEGRADATION OF BARRIER SPITS IN AREAS WITH LOW RATES OF LITTORAL DRIFT* D.G. AUBREY and A.G. GAINES, Jr. Woods Hole Oceanographic Institution, Woods Hole, MA 02543 (U.S.A.) (Received February 8, 1982; revised and accepted April 6, 1982) ABSTRACT Aubrey, D.G. and Gaines Jr., A.G., 1982. Rapid formation and degradation of barrier spits in areas with low rates of littoral drift. Mar. Geol., 49: 257-278. A small barrier beach exposed to low-energy waves and a small tidal range (0.7 m) along Nantucket Sound, Mass., has experienced a remarkable growth phase followed by rapid attrition during the past century. In a region of low longshore-transport rates, the barrier spit elongated approximately 1.5 km from 1844 to 1954, developing beyond the baymouth, parallel to the adjacent Nantucket Sound coast. Degradation of the barrier spit was initiated by a succession of hurricanes in 1954 (Carol, Edna and Hazel). A breach opened and stabilized near the bay end of the one kilometer long inlet channel, providing direct access for exchange of baywater with Nantucket Sound, and separating the barrier beach into two nearly equal limbs. The disconnected northeast limb migrated shorewards, beginning near the 1954 inlet and progressing northeastward, filling the relict inlet channel behind it. At present, about ten percent of the northeast limb is subaerial: the rest of the limb has completely filled the former channel and disappeared. The southwest limb of the barrier beach has migrated shoreward, but otherwise has not changed significantly since the breach. -

Mass Audubon Annual Report 2020

2020 Annual Report Contents Cover Photo: Arcadia Wildlife Sanctuary Volunteer 01 Letter from the President & Board Chair 02 Fiscal Year 2020 Highlights 03 A Pivotal Pandemic 04 Successes Across the State 08 Land Conservation Summary Fiscal Year 2020 11 Supporters 17 Mass Audubon Board of Directors 2020 18 Mass Audubon Wildlife Sanctuaries, Nature Centers, & Museums Mass Audubon protects more than 38,000 acres of land throughout Massachusetts, saving birds and other wildlife, and making nature accessible to all. As Massachusetts’ largest nature conservation nonprofit, we welcome more than a half million visitors a year to our wildlife sanctuaries and 20 nature centers. From inspiring hilltop views to breathtaking coastal landscapes, serene woods, and working farms, we believe in protecting our state’s natural treasures for wildlife and for all people—a vision shared in 1896 by our founders, two extraordinary Boston women. Today, Mass Audubon is a nationally recognized environmental education leader, offering thousands of camp, school, and adult programs that get over 225,000 kids and adults outdoors every year. With more than 135,000 members and supporters, we advocate on Beacon Hill and beyond, and conduct conservation research to preserve the natural heritage of our beautiful state for today’s and future generations. We welcome you to explore a nearby sanctuary, find inspiration, and get involved. Learn how at massaudubon.org. Stony Brook Wildife Sanctuary The value and beauty of nature was on full display in 2020. As the global pandemic closed doors, more people than ever sought refuge outdoors, witnessing firsthand nature’s healing powers. Mass Audubon responded to this extraordinary time with passion, creativity, adaptability, and a singular focus on delivering on our mission, which has never been more important. -

Coast Guard, DHS § 80.525

Coast Guard, DHS Pt. 80 Madagascar Singapore 80.715 Savannah River. Maldives Surinam 80.717 Tybee Island, GA to St. Simons Is- Morocco Tonga land, GA. Oman Trinidad 80.720 St. Simons Island, GA to Amelia Is- land, FL. Pakistan Tobago Paraguay 80.723 Amelia Island, FL to Cape Canaveral, Tunisia Peru FL. Philippines Turkey 80.727 Cape Canaveral, FL to Miami Beach, Portugal United Republic of FL. Republic of Korea Cameroon 80.730 Miami Harbor, FL. 80.735 Miami, FL to Long Key, FL. [CGD 77–075, 42 FR 26976, May 26, 1977. Redes- ignated by CGD 81–017, 46 FR 28153, May 26, PUERTO RICO AND VIRGIN ISLANDS 1981; CGD 95–053, 61 FR 9, Jan. 2, 1996] SEVENTH DISTRICT PART 80—COLREGS 80.738 Puerto Rico and Virgin Islands. DEMARCATION LINES GULF COAST GENERAL SEVENTH DISTRICT Sec. 80.740 Long Key, FL to Cape Sable, FL. 80.01 General basis and purpose of demarca- 80.745 Cape Sable, FL to Cape Romano, FL. tion lines. 80.748 Cape Romano, FL to Sanibel Island, FL. ATLANTIC COAST 80.750 Sanibel Island, FL to St. Petersburg, FL. FIRST DISTRICT 80.753 St. Petersburg, FL to Anclote, FL. 80.105 Calais, ME to Cape Small, ME. 80.755 Anclote, FL to the Suncoast Keys, 80.110 Casco Bay, ME. FL. 80.115 Portland Head, ME to Cape Ann, MA. 80.757 Suncoast Keys, FL to Horseshoe 80.120 Cape Ann, MA to Marblehead Neck, Point, FL. MA. 80.760 Horseshoe Point, FL to Rock Island, 80.125 Marblehead Neck, MA to Nahant, FL. -

Cuttyhunk-Nantucket 24-Quadrangle Area of Cape Cod and Islands, Southeast Massachusetts

Prepared in cooperation with the Commonwealth of Massachusetts Office of the State Geologist and Executive Office of Energy and Environmental Affairs Surficial Geologic Map of the Pocasset-Provincetown- Cuttyhunk-Nantucket 24-Quadrangle Area of Cape Cod and Islands, Southeast Massachusetts Compiled by Byron D. Stone and Mary L. DiGiacomo-Cohen Open-File Report 2006-1260-E U.S. Department of the Interior U.S. Geological Survey U.S. Department of the Interior KEN SALAZAR, Secretary U.S. Geological Survey Marcia K. McNutt, Director U.S. Geological Survey, Reston, Virginia: 2009 For product and ordering information: World Wide Web: http://www.usgs.gov/pubprod Telephone: 1-888-ASK-USGS For more information on the USGS—the Federal source for science about the Earth, its natural and living resources, natural hazards, and the environment: World Wide Web: http://www.usgs.gov Telephone: 1-888-ASK-USGS Suggested citation: Stone, B.D., and DiGiacomo-Cohen, M.L., comps., 2009, Surficial geologic map of the Pocasset Provincetown-Cuttyhunk-Nantucket 24-quadrangle area of Cape Cod and Islands, southeast Massachusetts: U.S. Geological Survey Open-File Report 2006-1260-E. Any use of trade, product, or firm names is for descriptive purposes only and does not imply endorsement by the U.S. Government. Although this report is in the public domain, permission must be secured from the individual copyright owners to reproduce any copyrighted materials contained within this report. Cover figure. Photograph of eroding cliffs at Gay Head on Martha’s Vineyard (source: -

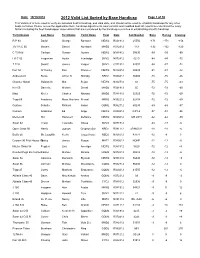

2012 Valid List Sorted by Base Handicap

Date: 10/19/2012 2012 Valid List Sorted by Base Handicap Page 1 of 30 This Valid List is to be used to verify an individual boat's handicap, and valid date, and should not be used to establish handicaps for any other boats not listed. Please review the appilication form, handicap adjustments, boat variants and modified boat list reports to understand the many factors including the fleet handicapper observations that are considered by the handicap committee in establishing a boat's handicap Yacht Design Last Name First Name Yacht Name Fleet Date Sail Number Base Racing Cruising R P 90 David George Rambler NEW2 R021912 25556 -171 -171 -156 J/V I R C 66 Meyers Daniel Numbers MHD2 R012912 119 -132 -132 -120 C T M 66 Carlson Gustav Aurora NEW2 N081412 50095 -99 -99 -90 I R C 52 Fragomen Austin Interlodge SMV2 N072412 5210 -84 -84 -72 T P 52 Swartz James Vesper SMV2 C071912 52007 -84 -87 -72 Farr 50 O' Hanley Ron Privateer NEW2 N072412 50009 -81 -81 -72 Andrews 68 Burke Arthur D Shindig NBD2 R060412 55655 -75 -75 -66 Chantier Naval Goldsmith Mat Sejaa NEW2 N042712 03 -75 -75 -63 Ker 55 Damelio Michael Denali MHD2 R031912 55 -72 -72 -60 Maxi Kiefer Charles Nirvana MHD2 R041812 32323 -72 -72 -60 Tripp 65 Academy Mass Maritime Prevail MRN2 N032212 62408 -72 -72 -60 Custom Schotte Richard Isobel GOM2 R062712 60295 -69 -69 -57 Custom Anderson Ed Angel NEW2 R020312 CAY-2 -57 -51 -36 Merlen 49 Hill Hammett Defiance NEW2 N020812 IVB 4915 -42 -42 -30 Swan 62 Tharp Twanette Glisse SMV2 N071912 -24 -18 -6 Open Class 50 Harris Joseph Gryphon Soloz NBD2 -

Mise En Page 1 23/10/2017 21:27 Page58

304RZEIT_58.qxp_Mise en page 1 23/10/2017 21:27 Page58 58 RIVIERA NAUTIK ereits im frühen 19. Jahrhundert wur - den in Cowes, Isle of Wight , Segelre - gatten ausgetragen. Eine war das AMERICA’S CUP B «Round the Island Race», zu dem an - lässlich der Londoner Weltausstellung Die berühmteste Sporttrophäe der Welt 1851 die Engländer ihre amerikani - schen Segelfreunde einluden. Extra für dieses Rennen Text & Grafik von GERHARD STANDOP wurde der 30 Meter lange Schoner America gebaut. Das Rennen gewannen die Amerikaner mit gutem Vorsprung vor den sonst so siegesgewohnten Engländern. Die fairen Verlierer lobten daraufhin eine spezielle Regatta aus und nannten sie nach der siegreichen Jacht «America’s Cup». Jener AC wurde 1870 erstmals ausgetragen. Man segelte Boot gegen Boot, der Cup-Verteidiger gegen den Heraus - forderer. Der America’s Cup war immer schon Tummelplatz für technische Innovationen, die meist unter größter Ge - heimhaltung entwickelt wurden. Die Syndikatsbosse wa- ren so eitel wie erfinderisch und liebten es, den Gegner mit eigenwilligen Regelauslegungen auszutricksen. Im Jahr 1903 verteidigte die amerikanische Reliance, ein Entwurf des berühmten Nathanael G. Herreshoff, den Cup erfolgreich. Sie war die erste Jacht, die mit Winschen America’s Cup» Dennis Connor. Von 1974 bis 1988 prägte und einem Ballast-Ruder ausgestattet war, und ist bis er das Geschehen des AC, ließ sich 1983 den Cup zwar heute das größte Boot, das jemals für den AC gebaut entreißen, holte ihn aber 1987 in die USA zurück – und wurde. Etwa 60 m lang, 60 m hoch, 60 Mann Besatzung gewann schon ein Jahr später erneut gegen Neuseeland. – hoffnungslos übertakelt und sehr schwer zu segeln. -

![Herreshoff Collection Guide [PDF]](https://docslib.b-cdn.net/cover/4530/herreshoff-collection-guide-pdf-1064530.webp)

Herreshoff Collection Guide [PDF]

Guide to The Haffenreffer-Herreshoff Collection The Design Records of The Herreshoff Manufacturing Company Bristol, Rhode Island The Francis Russell Hart Nautical Collection Kurt Hasselbalch Frances Overcash & Angela Reddin The Francis Russell Hart Nautical Collections MIT Museum Cambridge, Massachusetts © 1997 Massachusetts Institute of Technology All rights reserved. Published by The MIT Museum 265 Massachusetts Avenue Cambridge, Massachusetts 02139 TABLE OF CONTENTS Acknowledgments 3 Introduction 5 Historical Sketch 6 Scope and Content 8 Series Listing 10 Series Description I: Catalog Cards 11 Series Description II: Casting Cards (pattern use records) 12 Series Description III: HMCo Construction Record 13 Series Description IV: Offset Booklets 14 Series Description V: Drawings 26 Series Description VI: Technical and Business Records 38 Series Description VII: Half-Hull Models 55 Series Description VIII: Historic Microfilm 56 Description of Database 58 2 Acknowledgments The Haffenreffer-Herreshoff Project and this guide were made possible by generous private donations. Major funding for the Haffenreffer-Herreshoff Project was received from the Haffenreffer Family Fund, Mr. and Mrs. J. Philip Lee, Joel White (MIT class of 1954) and John Lednicky (MIT class of 1944). We are most grateful for their support. This guide is dedicated to the project donors, and to their belief in making material culture more accessible. We also acknowledge the advice and encouragement given by Maynard Bray, the donors and many other friends and colleagues. Ellen Stone, Manager of the Ships Plans Collection at Mystic Seaport Museum provided valuable cataloging advice. Ben Fuller also provided helpful consultation in organizing database structure. Lastly, I would like to acknowledge the excellent work accomplished by the three individuals who cataloged and processed the entire Haffenreffer-Herrehsoff Collection. -

Of Mentions of St. Augustin's Church and School in Newport Daily News, 1900-1940

Salve Regina University Digital Commons @ Salve Regina Patrick Murphy Collection on St. Augustin Parish and School Archives and Special Collections 7-29-2013 Index of mentions of St. Augustin's Church and School in Newport Daily News, 1900-1940 Patrick F. Murphy Follow this and additional works at: https://digitalcommons.salve.edu/st-augustin Part of the Catholic Studies Commons, Journalism Studies Commons, Liturgy and Worship Commons, and the Religious Education Commons Recommended Citation Murphy, Patrick F., "Index of mentions of St. Augustin's Church and School in Newport Daily News, 1900-1940" (2013). Patrick Murphy Collection on St. Augustin Parish and School. 2. https://digitalcommons.salve.edu/st-augustin/2 This Book is brought to you for free and open access by the Archives and Special Collections at Digital Commons @ Salve Regina. It has been accepted for inclusion in Patrick Murphy Collection on St. Augustin Parish and School by an authorized administrator of Digital Commons @ Salve Regina. For more information, please contact [email protected]. NPT DAILY NEWS INDEX-(1900-40) A VISIT FROM ST NICHOLAS-100 Years Old+24Dec23* Army/Navy YMCA,Open House,PIC+19Jun1939* A&P Opens,656-8 Thames St,-11*PIC-28Feb33*364 Thames St,Opens 4/29*Ad-28Apr1939* A&P-ThamesSt-NEW-2Dec07*PICS(3)-7Jun29* Abraham Blk.-PIC-29Jun1912* ADAM WAS A GENTLEMAN-20May03* Adams House-PIC-2Sept08* Agassiz,RL,Dies-31Jul 33* Agricultural Soc-25th-16*18May22*Air Transport,Inc,1st(RI)-13*20Jan30* Ahavis Achim,25th-7Dec36* Air Shipment,1st,Commercial Products,Businessmen/Chamber-PIC-16Nov27* Air Mail Poster,Mary Teehan,PIC-11*13*Week,Nat.,Npt Logo+16May38* Airline,NY/Narr.Bay,70 Mins,NEW-15Jun,3*5*PICS,5Jul 29*26*SKETCH+27Jun1923* Airline, PIC-28Jun,XED-31Jul,2Aug1923* AIRMEN, HYMN FOR-21Jan15* Airport,Plans,Near ISLAND. -

'Development of a Vpp Based Rating for J-Class Yachts'

‘Development of a Vpp based rating for J-Class Yachts’ Clay Oliver, Yacht Research International, and John Robinson, Wolfson Unit MTIA. Abstract The J-Class was originally one of a number of level rating classes, developed under the ‘Universal Rule’, rating at 76 feet. The class was designated for each of the three America’s Cup series from 1930 to 1937. Most of the yachts were either scrapped or laid up at the end of the 1930’s, but more recently interest in the class has revived. Following refits and restorations, and one complete rebuild, there is now a class association and interest in further builds is strong, with two new boats already well into construction and fit out. For several years, the J-Class Association has run regattas based upon a Time Correction Factor (TCF) calculated using the standard WinDesign Velocity Prediction Program (Vpp). In 2007, the Association transferred the operation of this rating system to the Wolfson Unit both as a measure of independence and further to refine the process. The form and proportion of the J-Class contrast dramatically with those of the modern yachts which have largely driven developments in VPP hydrodynamic formulations in recent years. This paper describes the some new formulations geared specifically to the J-Class yacht, and generally applicable to the traditional yacht. The fact that the keel and hull of the traditional yacht cannot be rationally delineated is an issue and an approach to obviate this problem is described. Data from 1936 towing tank experiments of 1/24th and 1/8th-scale J-Class models are reanalyzed for new J-Class Vpp formulations.