The Theatre of Dionysus

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

The Conditions of Dramatic Production to the Death of Aeschylus Hammond, N G L Greek, Roman and Byzantine Studies; Winter 1972; 13, 4; Proquest Pg

The Conditions of Dramatic Production to the Death of Aeschylus Hammond, N G L Greek, Roman and Byzantine Studies; Winter 1972; 13, 4; ProQuest pg. 387 The Conditions of Dramatic Production to the Death of Aeschylus N. G. L. Hammond TUDENTS of ancient history sometimes fall into the error of read Sing their history backwards. They assume that the features of a fully developed institution were already there in its earliest form. Something similar seems to have happened recently in the study of the early Attic theatre. Thus T. B. L. Webster introduces his excellent list of monuments illustrating tragedy and satyr-play with the following sentences: "Nothing, except the remains of the old Dionysos temple, helps us to envisage the earliest tragic background. The references to the plays of Aeschylus are to the lines of the Loeb edition. I am most grateful to G. S. Kirk, H. D. F. Kitto, D. W. Lucas, F. H. Sandbach, B. A. Sparkes and Homer Thompson for their criticisms, which have contributed greatly to the final form of this article. The students of the Classical Society at Bristol produce a Greek play each year, and on one occasion they combined with the boys of Bristol Grammar School and the Cathedral School to produce Aeschylus' Oresteia; they have made me think about the problems of staging. The following abbreviations are used: AAG: The Athenian Agora, a Guide to the Excavation and Museum! (Athens 1962). ARNon, Conventions: P. D. Arnott, Greek Scenic Conventions in the Fifth Century B.C. (Oxford 1962). BIEBER, History: M. Bieber, The History of the Greek and Roman Theatre2 (Princeton 1961). -

The Goddess Nike Article

MUSEUM FRIDAY FEATURE The Goddess Nike by Benton Kidd, Curator of Ancient Art nown as Nike to the Greeks (Latin: Victoria), the winged goddess of victory is familiar to many today, but she was far more than anotherK gratuitous, divine beauty. On the contrary, Nike played an integral role in ancient Greek culture, one which prided itself on the spirit of competition. While winning glory and fame is a persistent theme in Greek literature, actual contests of athletics, theater, poetry, art, music, military achievement—and even beauty— fueled the drive in ancient Greeks to achieve and win. One hymn lauds Nike as the one who confers the “mark of sweet renown,” concluding with “…you rule all things, divine goddess.” The widespread veneration of such a goddess is thus not unexpected, but she was not included among the august Olympians. In fact, her origins are likely to be earlier. In our previous discussion of the god Eros, we had occasion to mention Hesiod’s account of creation, known as the Theogony, or the “genesis of the gods.” Perhaps written about 700 BCE, this grand saga in poetry sweeps the reader back to an ancient era in which the Olympian gods engage in an epic battle with the Titans, a truculent race of primeval gods. Hesiod tells us that the battle raged for ten long years, and that the Olympian victory resulted in absolute supremacy over the universe. The Titans were imprisoned in Tartarus, a horrifying black abyss in the Underworld, reserved for punishing the vilest sinners. Some Titans, however, escaped this terrible fate. -

For Municipal Solid Waste Management in Greece

Journal of Open Innovation: Technology, Market, and Complexity Article Description and Economic Evaluation of a “Zero-Waste Mortar-Producing Process” for Municipal Solid Waste Management in Greece Alexandros Sikalidis 1,2 and Christina Emmanouil 3,* 1 Amsterdam Business School, Accounting Section, University of Amsterdam, 1012 WX Amsterdam, The Netherlands 2 Faculty of Economics, Business and Legal Studies, International Hellenic University, 57001 Thessaloniki, Greece 3 School of Spatial Planning and Development, Aristotle University of Thessaloniki, 54124 Thessaloniki, Greece * Correspondence: [email protected]; Tel.: +30-2310-995638 Received: 2 July 2019; Accepted: 19 July 2019; Published: 23 July 2019 Abstract: The constant increase of municipal solid wastes (MSW) as well as their daily management pose a major challenge to European countries. A significant percentage of MSW originates from household activities. In this study we calculate the costs of setting up and running a zero-waste mortar-producing (ZWMP) process utilizing MSW in Northern Greece. The process is based on a thermal co-processing of properly dried and processed MSW with raw materials (limestone, clay materials, silicates and iron oxides) needed for the production of clinker and consequently of mortar in accordance with the Greek Patent 1003333, which has been proven to be an environmentally friendly process. According to our estimations, the amount of MSW generated in Central Macedonia, Western Macedonia and Eastern Macedonia and Thrace regions, which is conservatively estimated at 1,270,000 t/y for the year 2020 if recycling schemes in Greece are not greatly ameliorated, may sustain six ZWMP plants while offering considerable environmental benefits. This work can be applied to many cities and areas, especially when their population generates MSW at the level of 200,000 t/y, hence requiring one ZWMP plant for processing. -

Storytelling and Community: Beyond the Origins of the Ancient

STORYTELLING AND COMMUNITY: BEYOND THE ORIGINS OF THE ANCIENT THEATRE, GREEK AND ROMAN by Sarah Kellis Jennings Submitted in partial fulfillment of the requirements for Departmental Honors in the Department of Theatre Texas Christian University Fort Worth, Texas May 3, 2013 ii STORYTELLING AND COMMUNITY: BEYOND THE ORIGINS OF THE ANCIENT THEATRE, GREEK AND ROMAN Project Approved: T.J. Walsh, Ph.D. Department of Theatre (Supervising Professor) Harry Parker, Ph.D. Department of Theatre Kindra Santamaria, Ph.D. Department of Modern Language Studies iii TABLE OF CONTENTS ACKNOWLEDGEMENTS ................................................................................................iv INTRODUCTION ...............................................................................................................1 GREEK THEATRE .............................................................................................................1 The Dithyramb ................................................................................................................2 Grecian Tragedy .............................................................................................................4 The Greek Actor ............................................................................................................. 8 The Satyr Play ................................................................................................................9 The Greek Theatre Structure and Technical Flourishes ...............................................10 Grecian -

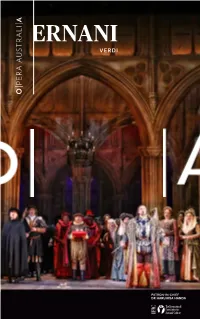

Ernani Program

VERDI PATRON-IN-CHIEF DR HARUHISA HANDA Celebrating the return of World Class Opera HSBC, as proud partner of Opera Australia, supports the many returns of 2021. Together we thrive Issued by HSBC Bank Australia Limited ABN 48 006 434 162 AFSL No. 232595. Ernani Composer Ernani State Theatre, Giuseppe Verdi (1813-1901) Diego Torre Arts Centre Melbourne Librettist Don Carlo, King of Spain Performance dates Francesco Maria Piave Vladimir Stoyanov 13, 15, 18, 22 May 2021 (1810-1876) Don Ruy Gomez de Silva Alexander Vinogradov Running time: approximately 2 hours and 30 Conductor Elvira minutes, including one interval. Carlo Montanaro Natalie Aroyan Director Giovanna Co-production by Teatro alla Scala Sven-Eric Bechtolf Jennifer Black and Opera Australia Rehearsal Director Don Riccardo Liesel Badorrek Simon Kim Scenic Designer Jago Thank you to our Donors Julian Crouch Luke Gabbedy Natalie Aroyan is supported by Costume Designer Roy and Gay Woodward Kevin Pollard Opera Australia Chorus Lighting Designer Chorus Master Diego Torre is supported by Marco Filibeck Paul Fitzsimon Christine Yip and Paul Brady Video Designer Assistant Chorus Master Paul Fitzsimon is supported by Filippo Marta Michael Curtain Ina Bornkessel-Schlesewsky and Matthias Schlesewsky Opera Australia Actors The costumes for the role of Ernani in this production have been Orchestra Victoria supported by the Concertmaster Mostyn Family Foundation Sulki Yu You are welcome to take photos of yourself in the theatre at interval, but you may not photograph, film or record the performance. -

The Form of the Orchestra in the Early Greek Theater

THE FORM OF THE ORCHESTRA IN THE EARLY GREEK THEATER (PLATE 89) T HE "orchestra" was essentially a dancing place as the name implies.' The word is generally used of the space between the seats and the scene-building in the ancient theater. In a few theaters of a developed, monumental type, such as at Epidauros (built no earlier than 300 B.C.), the orchestra is defined by a white marble curb which forms a complete circle.2 It is from this beautiful theater, known since 1881, and from the idea of a chorus dancing in a circle around an altar, that the notion of the orchestra as a circular dancing place grew.3 It is not surprising then that W. D6rpfeld expected to find an original orchestra circle when he conducted excavations in the theater of Dionysos at Athens in 1886. The remains on which he based his conclusions were published ten years later in his great work on the Greek theater, which included plans and descriptions of eleven other theaters. On the plan of every theater an orchestra circle is restored, although only at Epidauros does it actually exist. The last ninety years have produced a long bibliography about the form of the theater of Dionysos in its various periods and about the dates of those periods, and much work has been done in the field to uncover other theaters.4 But in all the exam- 1 opXeaat, to dance. Nouns ending in -arrpa signify a place in which some specific activity takes place. See C. D. Buck and W. -

The Art and Artifacts Associated with the Cult of Dionysus

Alana Koontz The Art and Artifacts Associated with the Cult of Dionysus Alana Koontz is a student at University of Wisconsin-Milwaukee graduating with a degree in Art History and a certificate in Ancient Mediterranean Studies. The main focus of her studies has been ancient art, with specific attention to ancient architecture, statuary, and erotic symbolism in ancient art. Through various internships, volunteering and presentations, Alana has deepened her understanding of the art world, and hopes to do so more in the future. Alana hopes to continue to grad school and earn her Master’s Degree in Art History and Museum Studies, and eventually earn her PhD. Her goal is to work in a large museum as a curator of the ancient collections. Alana would like to thank the Religious Studies Student Organization for this fantastic experience, and appreciates them for letting her participate. Dionysus was the god of wine, art, vegetation and also widely worshipped as a fertility god. The cult of Dionysus worshipped him fondly with cultural festivities, wine-induced ritualistic dances, 1 intense and violent orgies, and secretive various depictions of drunken revelry. 2 He embodies the intoxicating portion of nature. Dionysus, in myth, was the last god to be accepted at Mt Olympus, and was known for having a mortal mother. He spent his adulthood teaching the cultivation of grapes, and wine-making. The worship began as a celebration of culture, with plays and processions, and progressed into a cult that was shrouded in mystery. Later in history, worshippers would perform their rituals in the cover of darkness, limiting the cult-practitioners to women, and were surrounded by myth that is sometimes interpreted as fact. -

The HELLENIC OPEN BUSSINES ADMINISTRATION Journal

The HELLENIC OPEN BUSSINES ADMINISTRATION Journal Volume 2 - 2016, No 1 - Author Reprint Edited by: Dimitrios A. Giannias , Professor HELLENIC OPEN UNIVERSITY ISSN: 2407-9332 Athens 2016 Publisher: D. Giannias 1 The HELLENIC OPEN BUSINESS ADMINISTRATION Journal Volume 2 - 2016, No 1 The HELLENIC OPEN BUSINESS ADMINISTRATION Journal Publisher: D. Giannias / Athens 2016 ISSN: 2407-9332 www.hoba.gr 3 The HELLENIC OPEN BUSINESS ADMINISTRATION Journal The HELLENIC OPEN BUSINESS ADMINISTRATION JOURNAL AIMS AND SCOPE The HELLENIC OPEN BUSINESS ADMINISTRATION Journal is published two times a year and focuses on applied and theoretical research in business Administration and economics. Editor: Dimitrios A. Giannias, HELLENIC OPEN UNIVERSITY, Greece Associate Editors: Athanassios Mihiotis, HELLENIC OPEN UNIVERSITY, Greece Eleni Sfakianaki, HELLENIC OPEN UNIVERSITY, Greece Editorial Advisory Board: o M. Suat AKSOY, ERCIYES UNIVERSITY KAYSERI, Turkey o Charalambos Anthopoulos, HELLENIC OPEN UNIVERSITY, Greece o Christina Beneki, TECHNOLOGICAL EDUCATIONAL INSTITUTE OF IONIAN ISLANDS, Greece o George Blanas, TECHNOLOGICAL EDUCATIONAL INSTITUTE OF THESSALY, Greece o Chepurko Yuri, KUBAN STATE UNIVERSITY, Russia o Tuncay Çelik, ERCIYES UNIVERSITY KAYSERI, Turkey o Vida ČIULEVIČIENE, ALEKSANDRAS STULGINSKIS UNIVERSITY, Lithuania 5 The HELLENIC OPEN BUSINESS ADMINISTRATION Journal o Bruno Eeckels, LES ROCHES INTERNATIONAL SCHOOL OF HOTEL MANAGEMENT, Switzerland o Figus Alessandro, LINK CAMPUS UNIVERSITY & UNIVERSITY OF GENOVA, Italy o George Filis, UNIVERSITY -

THE DIONYSIAN PARADE and the POETICS of PLENITUDE by Professor Eric Csapo 20 February 2013 ERIC CSAPO

UCL DEPARTMENT OF GREEK AND LATIN HOUSMAN LECTURE UCL Housman Lecture THE DIONYSIAN PARADE AND THE POETICS OF PLENITUDE by Professor Eric Csapo 20 February 2013 ERIC CSAPO A.E. Housman (1859–1936) Born in Worcestershire in 1859, Alfred Edward Housman was a gifted classical scholar and poet. After studying in Oxford, Housman worked for ten years as a clerk, while publishing and writing scholarly articles on Horace, Propertius, Ovid, Aeschylus, Euripides and Sophocles. He gradually acquired such a high reputation that in 1892 he returned to the academic world as Professor of Classics at University College London (1892–1911) and then as Kennedy Professor of Latin at Trinity College, Cambridge (1911–1936). Housman Lectures at UCL The Department of Greek and Latin at University College London organizes regular Housman Lectures, named after its illustrious former colleague (with support from UCL Alumni). Housman Lectures, delivered by a scholar of international distinction, originally took place every second year and now happen every year, alternating between Greek and Roman topics (Greek lectures being funded by the A.G. Leventis Foundation). The fifth Housman lecture, which was given by Professor Eric Csapo (Professor of Classics, University of Sydney) on 20 February 2013, is here reproduced with minor adjustments. This lecture and its publication were generously supported by the A.G. Leventis Foundation. 2 HOUSMAN LECTURE The Dionysian Parade and the Poetics of Plenitude Scholarship has treated our two greatest Athenian festivals very differently.1 The literature on the procession of the Panathenaea is vast. The literature on the Parade (pompe) of the Great Dionysia is miniscule. -

Decentralization, Local Government Reforms and Perceptions of Local Actors: the Greek Case

Munich Personal RePEc Archive Decentralization, Local Government Reforms and Perceptions of Local Actors: The Greek Case Ioannidis, Panos 3 September 2015 Online at https://mpra.ub.uni-muenchen.de/66420/ MPRA Paper No. 66420, posted 04 Sep 2015 08:46 UTC Decentralization, Local Government Reforms and Perceptions of Local Actors: The Greek Case Dr. Panos Ioannidis Abstract Decentralization deployed in the last two decades in Greece via two local government reforms. Kapodistrias Plan and Kallikrates Project amalgamated successively the huge number of 5.775 municipalities and communities into 325 enlarged municipalities, institutionalized the 13 regions as second tiers of local government and transferred an unparalleled set of rights and powers to municipalities and regions. The abovementioned reforms changed the operation of local governments and established new conditions for the role of local actors in regional planning. This paper aims to assess the decentralization process in Greece, by taking into account the perceptions of local actors. A primary research was held in Eastern Macedonia and Thrace region, in order to understand the affiliation of local actors to the reforms. Results demonstrate that Kapodistrias reform had bigger social acceptance than Kallikrates, as economic crisis and rough spatial planning deter the effective implementation of the second wave of reforms. Non institutional actors and members of societal and cultural organizations perceived more substantially the reforms, than institutional actors and non members of local organizations did. Further improvements are necessary for the modernization of Greek local governments, in the fields of financial decentralization and administrative capacity Key Words: Decentralization, Local Government Reforms, Greece, Eastern Macedonia and Thrace JEL Classification: H73, R28, R58 Ph.D. -

The Newsletter Vol.1, in Accessible PDF Format

Reinforcing protected areas capacity through an innovative methodology for sustainability Newsletter 1: October 2018 BIO2CARE – A project that cares for the environment In this newsletter A Few Words for our Project • BIO2CARE – A project that cares for the Reinforcing protected areas capacity through an innovative methodology for environment sustainability “BIO2CARE” is a project approved for funding under the ✓ A Few Words for Greece-Bulgaria 2014-2020 territorial cooperation programme. BIO2CARE our Project falls under the Priority Axis 2: A Sustainable and Climate adaptable Cross- Border area, Thematic Objective 6: Preserving and protecting the ✓ Expected Results of environment and promoting resource efficiency, Investment Priority 6d: BIOCARE project Protecting and restoring biodiversity, soil protection and restoration and ✓ Our Partnership promoting ecosystem services including NATURA 2000 and green infrastructures. • Implementation of BIO2CARE project In full compliance with CBC GR-BG 2014-20 objective, BIO2CARE project • Activities of BIO2CARE overall objective is “To reinforce Protected Areas’ Management Bodies (PA project beneficiaries MBs) efficiency and effectiveness in an innovative and integrated approach”, promoting territorial cooperation in a very concrete and well-defined • Other News approach. BIO2CARE main objective is to enhance PA MBs administrative capacities on the benefit of biodiversity as of local communities. This is in full compliance with programme priority specific objective: “To enhance the effectiveness of biodiversity protection activities”. The Project is co-funded by the European Regional Development Fund and by national funds of the countries participating in the Interreg V-A "Greece-Bulgaria 2014-2020" Cooperation Programme. Page 1 The BIO2CARE proposed decision-making platform could become a valuable tool for understanding the activities and quantifying their respective impacts on biodiversity (e.g. -

Architects and Xenía in the Ancient Greek Theatre

RETURN TO ORIGINS SIMON WEIR On the origin of the architect: Architects and xenía in the ancient Greek theatre 17 INTERSTICES Introduction Seeking precedents for a language to explain architecture’s political and ethical functions, this paper is a historical case study focussed on the earliest ancient Greek records of architecture. This study reveals the ethical principle of xenía, a form of ritualised hospitality permeating architecture and directing architectural practice towards accommodating the needs of people broadly labeled foreigners. It will be shown that xenía in ancient Greek architectural thinking was so highly val- ued that even a fractional shift elicited criticism from Demosthenes and Vitruvius. This paper will use the definition ofxenía given by Gabriel Herman in Ritualised Friendship and the Greek City (1996), then add the four distinct kinds of foreigners given by Plato in Laws, and consider the hospitality offered to these foreigners by architects. Some forms of architectural hospitality such as hostels are closely tied to our contemporary sense of hospitality, but others are contingent on the cul- tural priorities of their day. When ancient Greek authors considered residential architecture and xenía together, it was explicitly in the context of a larger polit- ical framework about xenía and architecture; for Demosthenes and Vitruvius, architectural investment in residences showed diminished respect for xenía. The more unusual alliances between architects and xenía appear in the thea- tre, both in characters on stage and in the theatre’s furniture and temporary structures. Two early significant appearances of architects onstage in Athenian theatre were uncovered in Lisa Landrum’s 2010 doctoral thesis, “Architectural Acts: Architect-Figures in Athenian Drama and Their Prefigurations”, and her 2013 essay “Ensemble Performances: Architects and Justice in Athenian Drama” which references Aristophanes’ Peace and Euripides’ Cyclops.