Securitizing Women: Gender, Precaution, and Risk in Indian Finance

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Inception Meeting of State Financial Inclusion Forum (SFIF), Odisha

6th State Financial Inclusion Forum (SFIF), Odisha Theme: “PMJDY: Beyond Opening of Accounts” Date: 20th April 2015 (2.00-5.00pm) Venue: Hotel New Marrion , Bhubaneswar Proceedings of the Meeting Background: Small Industries Development Bank of India (SIDBI) in partnership with Department for International Development (DFID), UK, is implementing a bilateral project titled “Poorest States Inclusive Growth (PSIG)” programme. The programme aims at to facilitate better access to financial services by the poor and to promote pro-poor investments in India’s four poor states of Bihar, Odisha, Uttar Pradesh and Madhya Pradesh. The key mandate of the programme as earlier said is to improve access to both financial as well as non-credit services (savings, credit, insurance, pension, remittance, mobile banking, BCs etc.) for poor people and to strengthen the institutional framework so as to help the poor in improving their income and quality of life through multi-farious initiatives. ACCESS-ASSIST has been assigned by PSIG to coordinate the initiatives on policy advocacy in the above four states as well as at the National level. Setting up of multi-stakeholders State Financial Inclusion Forum (SFIF) in each PSIG focus state has been agreed as one of the key mechanisms to achieve the objectives under the policy advocacy component at the state level. The SFIF is expected to act as a platform to facilitate effective coordination and synergy among all stakeholders in creating an enabling environment and accelerating the process of financial inclusion in the state. As proposed in the 5th SFIF meeting held in January 2015, the 6th meeting was organized on the underlying theme of “PMJDY–Beyond Opening of Accounts”. -

State Bank of India

State Bank of India State Bank of India Type Public Traded as NSE: SBIN BSE: 500112 LSE: SBID BSE SENSEX Constituent Industry Banking, financial services Founded 1 July 1955 Headquarters Mumbai, Maharashtra, India Area served Worldwide Key people Pratip Chaudhuri (Chairman) Products Credit cards, consumer banking, corporate banking,finance and insurance,investment banking, mortgage loans, private banking, wealth management Revenue US$ 36.950 billion (2011) Profit US$ 3.202 billion (2011) Total assets US$ 359.237 billion (2011 Total equity US$ 20.854 billion (2011) Owner(s) Government of India Employees 292,215 (2012)[1] Website www.sbi.co.in State Bank of India (SBI) is a multinational banking and financial services company based in India. It is a government-owned corporation with its headquarters in Mumbai, Maharashtra. As of December 2012, it had assets of US$501 billion and 15,003 branches, including 157 foreign offices, making it the largest banking and financial services company in India by assets.[2] The bank traces its ancestry to British India, through the Imperial Bank of India, to the founding in 1806 of the Bank of Calcutta, making it the oldest commercial bank in the Indian Subcontinent. Bank of Madras merged into the other two presidency banks—Bank of Calcutta and Bank of Bombay—to form the Imperial Bank of India, which in turn became the State Bank of India. Government of Indianationalised the Imperial Bank of India in 1955, with Reserve Bank of India taking a 60% stake, and renamed it the State Bank of India. In 2008, the government took over the stake held by the Reserve Bank of India. -

Senior Unsecured Redeemable Non Convertible Debentures (Series - 5) of Rs.10 Lakh Each for Cash at Par with Base Issue Size of Rs

AXIS BANK LIMITED (Incorporated on 3rd December, 1993 under the Companies Act, 1956) CIN : L65110GJ1993PLC020769 Registered Office: “Trishul”, Third Floor, Opp. Samartheshwar Temple, Law Garden, Ellisbridge, Ahmedabad – 380 006. Tel No. 079 - 66306161, Fax No. 079 - 26409321 Website: www.axisbank.com Corporate Office: ‘Axis House’, C-2, Wadia International Centre, Pandurang Budhkar Marg, Worli, Mumbai – 400025. Contact Person: Mr. Girish Koliyote, Senior Vice-President & Company Secretary Email address: [email protected] DISCLOSURE DOCUMENT PRIVATE PLACEMENT OF SENIOR UNSECURED REDEEMABLE NON CONVERTIBLE DEBENTURES (SERIES - 5) OF RS.10 LAKH EACH FOR CASH AT PAR WITH BASE ISSUE SIZE OF RS. 2000 CRORE (TWO THOUSAND CRORE) AND GREENSHOE OPTION TO RETAIN OVERSUBSCRIPTION OF RS. 3000 CRORE (THREE THOUSAND CRORE) THEREBY AGGREGATING UPTO RS. 5000 CRORE (RUPEES FIVE THOUSAND CRORE ONLY) ISSUER’S ABSOLUTE RESPONSIBILITY The Issuer, having made all reasonable inquiries, accepts responsibility for and confirms that this Disclosure Document contains information with regard to the Issuer and the issue, which is material in the context of the issue, that the information contained in the Disclosure Document is true and correct in all material aspects and is not misleading in any material respect, that the opinions and intentions expressed herein are honestly held and that there are no other facts, the omission of which make this document as a whole or any of such information or the expression of any such opinions or intentions misleading in any material respect. LISTING The said Unsecured Redeemable Non-Convertible Senior Debentures are proposed to be listed on the National Stock Exchange of India Limited (NSE) and The BSE Limited (BSE). -

2349-6746 Issn

Research Paper IJMSRR Impact Factor: 5.483 E- ISSN - 2349-6746 Peer Reviewed & Indexed Journal ISSN -2349-6738 MEGA MERGER OF SBI: EMPLOYEES’ ATTITUDE AND ADAPTABILITY Merliyn Anna Thomas Guest Lecturer, Post Graduate Department of Commerce and Research Centre, St.Thomas College, Kozhencherry. Abstract Mergers have become an increasingly common reality of organisational life. Mergers promote the entities to develop, condense and alter the nature of their competitive position. In addition, during this time, it is a common scene of employees with stress, fear and anxiety. They may have fears concerning job loss, job changes, compensation, workload, working hours and so on. The attitude of an employee resulting from the merger will certainly affect his work related behavior; consequently, the efficiency and output of the company suffer. On 15 Feb 2017, the Union Cabinet approved a proposal to merge 5 associate banks with SBI. Merger of SBI with its 5 associate banks and Bharatiya Mahila Bank is the largest merger in history of Indian Banking Industry.” In any merger, the biggest challenge is always integration of human resources because the people who are coming in have a lot of apprehension” said Arundhati Bhattacharya, former Chairman, SBI. This paper highlights the attitude and adaptability of employees towards merger of associate banks with SBI and also compares the pre-merger and post-merger position of employees. Responses from SBI employees were obtained and it is found that even though the merger has brought certain increases in their workload and responsibility, they are adaptable with the merger process. It is hoped that this study will help those who are interested in knowing the human side of mega merger of SBI. -

Payment Gateway

PAYMENT GATEWAY APIs for integration Contact Tel: +91 80 2542 2874 Email: [email protected] Website: www.traknpay.com Document version 1.7.9 Copyrights 2018 Omniware Technologies Private Limited Contents 1. OVERVIEW ............................................................................................................................................. 3 2. PAYMENT REQUEST API ........................................................................................................................ 4 2.1. Steps for Integration ..................................................................................................................... 4 2.2. Parameters to be POSTed in Payment Request ............................................................................ 5 2.3. Response Parameters returned .................................................................................................... 8 3. GET PAYMENT REQUEST URL (Two Step Integration) ........................................................................ 11 3.1 Steps for Integration ......................................................................................................................... 11 3.2 Parameters to be posted in request ................................................................................................. 12 3.3 Successful Response Parameters returned ....................................................................................... 12 4. PAYMENT STATUS API ........................................................................................................................ -

Working Conditions of Women in Public Sector Banks '

4 PARLIAMENT OF INDIA LOK SABHA COMMITTEE ON EMPOWERMENT OF WOMEN (2014-2015) (SIXTEENTH LOK SABHA) FOURTH REPORT ‘WORKING CONDITIONS OF WOMEN IN PUBLIC SECTOR BANKS ' LOK SABHA SECRETARIAT NEW DELHI August, 2015/Shravana, 1937 (Saka) FOURTH REPORT COMMITTEE ON EMPOWERMENT OF WOMEN (2014-2015) (SIXTEENTH LOK SABHA) ‘WORKING CONDITIONS OF WOMEN IN PUBLIC SECTOR BANKS' Presented to Lok Sabha on …..th August, 2015 Laid in Rajya Sabha on …..th August, 2015 LOK SABHA SECRETARIAT NEW DELHI August, 2015/Shravana, 1937 (Saka) E.W.C. No. 95 PRICE: Rs._____ © 2015 BY LOK SABHA SECRETARIAT Published under ……………………………………… CONTENTS Page Nos. Composition of the Committee on Empowerment of Women(2014-2015) (III) Introduction (v) REPORT PART I NARRATION ANALYSIS I. Introductory………………………………………………………………... 1 II. Women employees in PSBs, their recruitment & promotion………. 3 III. Women employees at higher grades in PSBs ……………………… 5 IV. Transfer/Posting of women employees in PSBs ……………………. 7 V. Welfare benefits for women employees in PSBs …. 9 VI. Dealing with the cases of sexual harassment in PSBs …………….. 13 VII. Job Related stress: Need to address it………………………………. 17 VIII. Training and capacity building measures ……………………………. 18 IX Flexi-working hour policy for women employees…………………... 19 X All-women banks, branches and Bharatiya Mahila Bank …………. 21 XI Women employees in rural branches and branches in North-East regions……………………………………………………………………… 22 PART II Observations/Recommendations of the Committee………………….. 24 ANNEXURES I. Women officers recruited in last 5years….……………………… 34 II. Number of posts reserved for ST/SC/OBC……………………… 35 III. Recommendations of the Khandelwal Committee……………… 36 IV. Grant of sabbatical leave to the women employees…………… 42 V. -

Ééì¹éeò |Éêié´Éänùxé ANNUAL REPORT Shri Pankaj Patel

Th 2016-17 ´ÉÉ̹ÉEò |ÉÊiÉ´ÉänùxÉ ANNUAL REPORT Shri Pankaj Patel Shri Kumar Mangalam Birla TH 2016-17 ´ÉÉ̹ÉEò |ÉÊiÉ´ÉänùxÉ ANNUAL REPORT Indian Institute of Management Ahmedabad th 55 Annual Report 2 2016-17 THE YEAR IN RETROSPECT 5 ACADEMIC PROGRAMMES 10 1. POST-GRADUATE PROGRAMME IN MANAGEMENT (PGP) 10 2. POST-GRADUATE PROGRAMME IN FOOD AND AGRI-BUSINESS MANAGEMENT (PGP-FABM) 14 3. POST-GRADUATE PROGRAMME IN MANAGEMENT FOR EXECUTIVES (PGPX) 16 4. FELLOW PROGRAMME IN MANAGEMENT 17 PLACEMENT 18 CONVOCATION 22 FACULTY DEVELOPMENT PROGRAMME IN MANAGEMENT 23 RESEARCH AND PUBLICATIONS 24 CASE CENTRE 26 EXECUTIVE EDUCATION PROGRAMMES 27 INTERDISCIPLINARY CENTRES AND GROUPS 28 1. CENTRE FOR GENDER EQUITY, DIVERSITY, AND INCLUSIVITY 28 2. CENTRE FOR INNOVATION INCUBATION AND ENTREPRENEURSHIP 29 3. INDIA GOLD POLICY CENTRE 33 4. CENTRE FOR MANAGEMENT IN AGRICULTURE 35 5. CENTRE FOR MANAGEMENT OF HEALTH SERVICES 35 6. CENTRE FOR RETAILING 37 7. PUBLIC SYSTEMS GROUP 37 8. RAVI J. MATTHAI CENTRE FOR EDUCATIONAL INNOVATION 38 DISCIPLINARY AREAS 39 1. BUSINESS POLICY 39 2. COMMUNICATION 40 3. ECONOMICS 40 3 CONTENT 4. FINANCE AND ACCOUNTING 41 5. HUMAN RESOURCE MANAGEMENT 42 6. INFORMATION SYSTEMS 43 7. MARKETING 43 8. ORGANIZATIONAL BEHAVIOUR 44 9. PRODUCTION AND QUANTITATIVE METHODS 45 ALUMNI ACTIVITIES 47 COMMUNICATION, PUBLIC RELATIONS, AND DIGITAL MARKETING 52 GLOBAL PARTNERSHIP AND CORPORATE AFFAIRS 53 GRANT-IN-AID 59 INFRASTRUCTURE DEVELOPMENT 60 OFFICIAL LANGUAGE IMPLEMENTATION 61 PERSONNEL 62 STUDENT ACTIVITIES 63 VIKRAM SARABHAI LIBRARY 79 WELFARE ACTIVITIES 81 Appendices 85 Vision Educating Leaders of Enterprises Mission To transform India and other countries through generating and propagating new ideas of global significance based on research and creation of risk-taking leader-managers who change managerial and administrative practices to enhance performance of organizations. -

Annual Report 2017-18

Annual Report 2017-18 Persistence is the Cornerstone of Success NEVER UNDERESTIMATE THE POWER OF PERSISTENCE here is an inherent strength in persistence. It can whittle down obstacles and Tchallenges like the way a river cuts through a rock, not because of its power but because of its persistence. Guided by a definite purpose, backed by a burning desire of achievement, steered by a clear-cut plan, persistence can open up any door closed by the resistance of problems. Results are simply inevitable. The ability to never give up, never lose faith and the loyalty towards being a part of the solution rather than the problem have been the providers of our success and progress over the past three decades. As one of India's leading Investment Banks and project advisers, we find ways not excuses to deliver cutting-edge solutions for our clients which, in turn has helped shape the Indian infrastructure story and contributed to nation building. While achieving this, the compelling reason for our victory over all odds has been our habit of persistence. We staunchly believe as long as we persist, we will be successful. ANNUAL REPORT 2017 - 2018 1 VISION To be the best India based Investment Bank. MISSION To provide credible, professional and customer focused world-class investment banking services. Persistent intent and determined action are an unbeatable combination for success. INDEX Board of Directors ..................................................................................................... 05 Awards & Rankings .................................................................................................. -

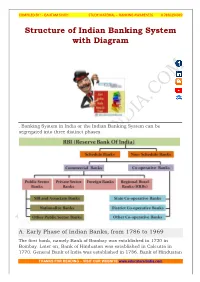

Structure of Indian Banking System with Diagram

COMPILED BY : - GAUTAM SINGH STUDY MATERIAL – BANKING AWARENESS 0 7830294949 Structure of Indian Banking System with Diagram . Banking System in India or the Indian Banking System can be segregated into three distinct phases: A. Early Phase of Indian Banks, from 1786 to 1969 The first bank, namely Bank of Bombay was established in 1720 in Bombay. Later on, Bank of Hindustan was established in Calcutta in 1770. General Bank of India was established in 1786. Bank of Hindustan THANKS FOR READING – VISIT OUR WEBSITE www.educatererindia.com COMPILED BY : - GAUTAM SINGH STUDY MATERIAL – BANKING AWARENESS 0 7830294949 carried on the business till 1906. First Joint Stock Bank with limited liability established in India in 1881 was Oudh Commercial Bank Ltd. East India Company established the three independently functioning banks, also known by the name of “Three Presidency Banks” - The Bank of Bengal in 1806, The Bank of Bombay in 1840, and Bank of Madras in 1843. These three banks were amalgamated in 1921 and given a new name as Imperial Bank of India. After Independence, in 1955, the Imperial Bank of India was given the name "State Bank of India". It was established under State Bank of India Act, 1955. In the surcharged atmosphere of Swadeshi Movement, a number of private banks with Indian managements had been established by the businessmen from mid of the 19th century onwards, prominent among them being Punjab National Bank Ltd., Bank of India Ltd., Canara Bank Ltd, and Indian Bank Ltd. The first bank with fully Indian management was Punjab National Bank Ltd. established on 19 May 1894, in Lahore (now in Pakistan). -

Sustainable Economic Growth Through Financial Inclusion in India

© 2018 JETIR October 2018, Volume 5, Issue 10 www.jetir.org (ISSN-2349-5162) Sustainable Economic Growth through Financial Inclusion in India Dr. Brijendra Singh Boudha 1 Bijendra Kumar 2 1Seniour Lecturer, Bundelkhand College, Jhansi. 2Research Scholar, Bundelkand University, Jhansi Abstract: Poverty eradication is consider as an important objective of the financial inclusion scheme since they bridge up the gap between the weaker section of society and the sources of livelihood and the means of income which can be generated for them if they get loans and advances. In order to ensure financial inclusion of the poor, particularly in rural areas, various initiatives have been taken by the government of India and Reserve bank of India (RBI) from time to time. These have included nationalization of commercial bank in 1969 and 1980.The establishment and expansion of rural credit co-operatives, regional rural bank, urban co-operative banks, micro finance and self-help group, mutual fund, and Pradhan Mantri Jan-Dhan Yougna (PMJDY), 2014. Multiple steps have been initiated by the RBI over the years to increase credit access to the poor section of the society. Keywords: Financial Inclusion; Inclusive Growth; Financial Services; Indian Financial Services; Indian Economy Introduction The concept of financial inclusion has a special significance for a fast-emerging economy such as India, as it encompasses a large segment of the productive sectors of the economy under formal financial network to unleash their creative capacities. Over a period of time, several financial' and economic policy measures are being taken by the banks in India to improve access to affordable financial services through financial education, awareness generation, business communication networking and leveraging technology. -

Indian Banks: Tacking Into the Wind Table of Contents

INDIAN BANKS: TACKING INTO THE WIND TABLE OF CONTENTS EXECUTIVE SUMMARY 5 1 THE INDIAN BANKING SECTOR: TAKING STOCK 9 1.1 THE JOURNEY SO FAR 9 1.2 CRITICAL JUNCTURES LIE AHEAD 12 1.3 THE WAY FORWARD 14 2 FIX THE FUNDAMENTALS 15 AGENDA 1. ENHANCE TRANSPARENCY 16 AGENDA 2. DRIVE A BROAD-BASED TRANSFORMATION IN RISK AND CAPITAL MANAGEMENT CAPABILITIES 18 AGENDA 3. PLUG THE GAPS AND CLEAR THE MUCK IN CREDIT MANAGEMENT 23 3 REINVENT BUSINESS MODELS 29 AGENDA 4. SME 2.0: PUSH THE FINAL FRONTIER 30 AGENDA 5. RETAIL BANKING: EMBRACE DIGITAL TECHNOLOGY AND DEVELOP A REAL PROPOSITION FOR AFFORDABLE BANKING 34 AGENDA 6. CORPORATE BANKING: PUSH NEW FRONTIERS TO DRIVE EXCELLENCE IN EXECUTION 38 4 DON’T IGNORE SOFTER ASPECTS 43 AGENDA 7. ADDRESS KEY HUMAN RESOURCE CHALLENGES 43 AGENDA 8. STRENGTHEN GOVERNANCE, COMPLIANCE, AND CULTURE 46 ADDITIONAL READING 50 Copyright © 2016 Oliver Wyman 2 And once the storm is over, “ you won’t remember how you made it through, how you managed to survive. You won’t even be sure whether the storm is really over. But one thing is certain. When you come out of the storm, you won’t be the same person who walked in. That’s what the storm is all about. — HARUKI MURAKAMI” EXECUTIVE SUMMARY 2016 marks a quarter of a century since India’s landmark reforms of 1991 were initiated, ushering in monumental changes to the economy and substantially liberalising the banking sector. Fuelled by a re-energised financial sector, the nation has gone from something of a footnote in the world economy to one of its most closely watched stars, becoming the world’s third largest in terms of purchasing power parity. -

DIGITAL PAYMENTS BOOK Part1

DIGITAL PAYMENTS Trends, Issues And Opportunities July 2018 FOREWORD A Committee on Digital Payments was growth figures for both volume and value. constituted by Department of Economic Notwithstanding this the analysis finds that Affairs, Ministry of Finance in August 2016 both the data are relevant and equally under my Chairmanship to inter-alia important. They are complementary. In recommend medium term measures of addition to this the underlying growth trends promotion of Digital Payments Ecosystem in Digital Payments over the last seven in the country. The Committee submitted its years are also covered in this booklet. final report to Hon’ble Finance Minister in December 2016. One of the key This booklet has some new chapters which recommendations of the Committee related cover the areas of policy developments, to development of a metric for Digital global trends and opportunities in Digital Payments. As a follow-up on this a group of Payments. In the policy space the important Stakeholders from Different Departments of developments with respect to the Government of India and RBI was amendment of the Payment and Settlement constituted in NITI Aayog under my Act 2007 are covered. chairmanship to facilitate the work relating I am grateful to Governor, RBI, Secretary to development of the metric. This group MeitY and CEO, NPCI for their support in prepared a document on the measurement preparing this booklet. Shri. B.N. Satpathy, issues of Digital Payments. Accordingly, a Senior Consultant, EAC-PM and Shri. booklet titled “Digital Payments: Trends, Suneet Mohan, Young Professional, NITI Issues and Challenges” was prepared in Aayog have played a key role in compiling May 2017 and was released by me in July this booklet.