Ethical and Sociocultural Considerations for Use of Assisted Reproductive Technologies Among the Baganda of Uganda

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

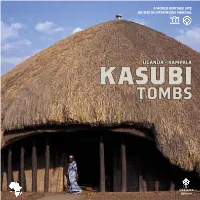

Buganda Kingdom Pictures of The: Kasubi Tombs (World Heritage Site

Buganda Kingdom pictures of the: Kasubi Tombs (World Heritage Site), Kabaka Mutebi(King), Nabagereka(Queen), Buganda Lukiiko(Parliament), Twekobe(Kings Residence), Buganda Flag(Blue) and the Uganda Flag and Court of Arms. 1 The map of Uganda showing Buganda Kingdom in the Central around Lake Victoria, and a little girl collecting unsafe drinking water from the lake. A Japanese Expert teaching a group of farmers Irrigation and Drainage skills for growing Paddy Rice in Eastern Uganda- Doho Rice Irrigation Scheme. 2 Brief about Uganda and Buganda Kingdom The Republic of Uganda is a land locked country bordered on the east by Kenya, on the north by Sudan, on the west by the Democratic republic of Congo, on the southwest by Rwanda, and on the south by Tanzania. The southern part of the country includes a substantial portion of Lake Victoria, which is also bordered by Kenya and Tanzania. The current estimated population of Uganda is 32.4 million. Uganda has a very young population, with a median age of 15 years. It is a member of the African Union, the Commonwealth of Nations, Organisation of the Islamic Conference and East African Community. History of the people Uganda: The people of Uganda were hunter-gatherers until 1,700 to 2,300 years ago. Bantu-speaking populations, who were probably from central and western Africa, migrated to the southern parts of the country. These groups brought and developed ironworking skills and new ideas of social and political organization. The Empire of Kitara in the fourteenth and fifteenth centuries represents the earliest forms of formal organization, followed by the kingdom of Bunyoro-Kitara, and in later centuries, Buganda and Ankole. -

A History of Ethnicity in the Kingdom of Buganda Since 1884

Peripheral Identities in an African State: A History of Ethnicity in the Kingdom of Buganda Since 1884 Aidan Stonehouse Submitted in accordance with the requirements for the degree of Ph.D The University of Leeds School of History September 2012 The candidate confirms that the work submitted is his own and that appropriate credit has been given where reference has been made to the work of others. This copy has been supplied on the understanding that it is copyright material and that no quotation from the thesis may be published without proper acknowledgement. Acknowledgments First and foremost I would like to thank my supervisor Shane Doyle whose guidance and support have been integral to the completion of this project. I am extremely grateful for his invaluable insight and the hours spent reading and discussing the thesis. I am also indebted to Will Gould and many other members of the School of History who have ably assisted me throughout my time at the University of Leeds. Finally, I wish to thank the Arts and Humanities Research Council for the funding which enabled this research. I have also benefitted from the knowledge and assistance of a number of scholars. At Leeds, Nick Grant, and particularly Vincent Hiribarren whose enthusiasm and abilities with a map have enriched the text. In the wider Africanist community Christopher Prior, Rhiannon Stephens, and especially Kristopher Cote and Jon Earle have supported and encouraged me throughout the project. Kris and Jon, as well as Kisaka Robinson, Sebastian Albus, and Jens Diedrich also made Kampala an exciting and enjoyable place to be. -

Scandal and Mass Politics: Buganda's 1941 Nnamasole Crisis Carol Summers University of Richmond, [email protected]

University of Richmond UR Scholarship Repository History Faculty Publications History 2018 Scandal and Mass Politics: Buganda's 1941 Nnamasole Crisis Carol Summers University of Richmond, [email protected] Follow this and additional works at: https://scholarship.richmond.edu/history-faculty-publications Part of the History Commons, and the Political Science Commons Recommended Citation Summers, Carol. "Scandal and Mass Politics: Buganda's 1941 Nnamasole Crisis." International Journal of African Historical Studies 51, no. 1 (2018): 63-83. This Article is brought to you for free and open access by the History at UR Scholarship Repository. It has been accepted for inclusion in History Faculty Publications by an authorized administrator of UR Scholarship Repository. For more information, please contact [email protected]. International Journal of African Historical Studies Vol. 51, No. 1 (2018) 63 Scandal and Mass Politics: Buganda’s 1941 Nnamasole Crisis By Carol Summers University of Richmond ([email protected]) In February of 1941, Irene Namaganda, Buganda’s queen mother, informed Buganda’s prime minister, Uganda’s Bishop, and eventually British administrators of the Uganda Protectorate, that she was six months pregnant, and intended to marry her lover. That lover was only slightly older than Mutesa II, her teenage son who had been selected as kabaka (king) in 1939. Despite reservations, the kingdom’s prime minister and his allies among Buganda’s protestant oligarchy worked with Uganda’s British officials to facilitate the marriage. Namaganda’s Christian marriage, though, was powerfully scandalous, profoundly violating expectations associated with marriage and royal office. The scandal produced a political crisis that toppled Buganda’s prime minister, pushed his senior allies from power, deposed the queen mother, exiled her husband, and changed Buganda’s political landscape. -

Buganda Relations in 19Th and 20Th Centuries

Bunyoro-Kitara/ Buganda relations in 19th and 20th Centuries. By Henry Ford Miirima Veteran journalist Press Secretary of the Omukama of Bunyoro-Kitara The source of sour relations. In order to understand the relations between Bunyoro-Kitara and Buganda kingdoms in the 19th and 20th centuries, one must first know the origins of the sour relations. The birth of Buganda, after seceeding from Bunyoro-Kitara was the source of hostile relations. This article will show how this sad situation was arrived at. Up to about 1500 Kitara kingdom (today's Bunyoro-Kitara) under Abatembuzi and Abacwezi dynasities was peaceful, intact, with no rebellious princes. When the Abacwezi kings disappeared they left a three-year vacuum on the throne which was filled when four Ababiito princes were traced, and collected from their Luo mother in northern Uganda. They ascended the Kitara throne with their elder, twin brother, Isingoma Mpuuga Rukidi becoming the first Mubiito king. The Babiito dynasity continues today (January 2005) to reign in Bunyoro-Kitara, Buganda, Busoga, Tooro, Kooki, and Ankole. The Abacwezi kings left: behind a structure of local administration based on counties. Muhwahwa(lightweight)county, todays Buganda, was just one of Kitara's counties. In the pages ahead we are going to see that the counties admninistrative strucuture is also the cause of bad relations between. Bunyoro and Buganda. Muhwahwa's small size, hence the need to expand it, as we are about to see in the pages ahead, had a lasting bearing on the relations not only between Bunyoro-Kitara and Buganda, but also between Buganda and the rest of today's Uganda During Abacwezi reign Muhwahwa county under chief Sebwana, was very obedient, and extremely loyal to Bunyoro-Kitara kingdom. -

Political Theologies in Late Colonial Buganda

POLITICAL THEOLOGIES IN LATE COLONIAL BUGANDA Jonathon L. Earle Selwyn College University of Cambridge This dissertation is submitted for the degree of Doctor of Philosophy 2012 Preface This dissertation is the result of my own work and includes nothing which is the outcome of work done in collaboration except where specifically indicated in the text. It does not exceed the limit of 80,000 words set by the Degree Committee of the Faculty of History. i Abstract This thesis is an intellectual history of political debate in colonial Buganda. It is a history of how competing actors engaged differently in polemical space informed by conflicting histories, varying religious allegiances and dissimilar texts. Methodologically, biography is used to explore three interdependent stories. First, it is employed to explore local variance within Buganda’s shifting discursive landscape throughout the longue durée. Second, it is used to investigate the ways that disparate actors and their respective communities used sacred text, theology and religious experience differently to reshape local discourse and to re-imagine Buganda on the eve of independence. Finally, by incorporating recent developments in the field of global intellectual history, biography is used to reconceptualise Buganda’s late colonial past globally. Due to its immense source base, Buganda provides an excellent case study for writing intellectual biography. From the late nineteenth century, Buganda’s increasingly literate population generated an extensive corpus of clan and kingdom histories, political treatises, religious writings and personal memoirs. As Buganda’s monarchy was renegotiated throughout decolonisation, her activists—working from different angles— engaged in heated debate and protest. -

Kasubi Tombs

A WORLD HERITAGE SITE UN SITE DU PATRIMOINE MONDIAL UGANDA - KAMPALA KASUBI TOMBS CRATerre Editions CRATerre Editions UGANDA - KAMPALA KASUBI TOMBS 2 KASUBI TOMBS KASUBI TOMBS 3 KASUBI TOMBS A WORLD HERITAGE SITE The preparation of this booklet was sponsored by the French Embassy in Kampala, and its conception is UN SITE DU PATRIMOINE MONDIAL the result of the cooperation between Heritage Trails Uganda, the National Department of Antiquities and Department of Antiquities and Museums Museums of Uganda, and CRATerre, research centre Kabaka Foundation of the Grenoble school of architecture in France. By Heritage Trails Uganda purchasing this booklet, the postcards or the poster, CRATerre-EAG you participate in the promotion and French Embassy in Kampala conservation of 7 Ganda sites, including the Kasubi Tombs, World Heritage Site, since part of the money you pay is invested in the regular maintenance of the thatched roofs. Ce fascicule, dont l’élaboration a été financée par l’ambassade de France en Ouganda, résulte d’un travail commun entre le Heritage Trails Uganda, le Département National des Musées et Antiquités de l’Ouganda et CRATerre, centre de recherche de l’école d’architecture de Grenoble en France. En achetant ce fascicule, les cartes postales ou le poster de la même série, vous participez à la promotion et à la conservation de 7 sites culturels du Bouganda, dont les tombes Kasubi, site du patrimoine mondial, car une partie des recettes de la vente de ces produits est investie dans l’entretien régulier des toitures de chaume. Kabata Mutesa’s Palace at Kasubi-Nabulagala (from the plan drawn by Sir Apolo Kagwa) Gate house (Bujjabukula) at the entrance of the site. -

Tombs of Buganda Kings at Kasubi

WHC Nomination Documentation File Name: 1022.pdf UNESCO Region: AFRICA __________________________________________________________________________________________________ SITE NAME: Tombs of Buganda Kings at Kasubi DATE OF INSCRIPTION: 16th December 2001 STATE PARTY: UGANDA CRITERIA: C (i) (iii) (iv) (vi) DECISION OF THE WORLD HERITAGE COMMITTEE: Excerpt from the Report of the 25th Session of the World Heritage Committee The Committee inscribed the Tombs of Buganda Kings at Kasubi on the World Heritage List under criteria (i), (iii), (iv), and (vi): Criterion (i): The Kasubi Tombs site is a masterpiece of human creativity both in its conception and in its execution. Criterion (iii): The Kasubi Tombs site bears eloquent witness to the living cultural traditions of the Baganda. Criterion (iv): The spatial organization of the Kasubi Tombs site represents the best extant example of a Baganda palace/architectural ensemble. Built in the finest traditions of Ganda architecture and palace design, it reflects technical achievements developed over many centuries. Criterion (vi): The built and natural elements of the Kasubi Tombs site are charged with historical, traditional, and spiritual values. It is a major spiritual centre for the Baganda and is the most active religious place in the kingdom. The Committee noted that the site combines the historical and spiritual values of a nation. BRIEF DESCRIPTIONS The Tombs of Buganda Kings at Kasubi constitute a site embracing almost 30 ha of hillside within Kampala district. Most of the site is agricultural, farmed by traditional methods. At its core on the hilltop is the former palace of the Kabakas of Buganda, built in 1882 and converted into the royal burial ground in 1884. -

The Restoration of the Buganda Kingship

CMIWORKINGPAPER Kingship in Uganda The Role of the Buganda Kingdom in Ugandan Politics Cathrine Johannessen WP 2006: 8 Kingship in Uganda The Role of the Buganda Kingdom in Ugandan Politics Cathrine Johannessen WP 2006: 8 CMI Working Papers This series can be ordered from: Chr. Michelsen Institute P.O. Box 6033 Postterminalen, N-5892 Bergen, Norway Tel: + 47 55 57 40 00 Fax: + 47 55 57 41 66 E-mail: [email protected] www.cmi.no Price: NOK 50 ISSN 0805-505X ISBN 82-8062-147-4 This report is also available at: www.cmi.no/publications Indexing terms Politics History Buganda Uganda Project title The legal and institutional context of the 2006 elections in Uganda Project number 24076 Contents 1. INTRODUCTION ........................................................................................................................................ 1 2. HISTORICAL CONSIDERATIONS: THE KABAKA AND HIS PEOPLE .......................................... 2 2.1 TOWARDS INDEPENDENCE......................................................................................................................... 3 2.2 THE 1966 CRISIS ........................................................................................................................................ 4 2.3 BUGANDA AND THE NATIONAL RESISTANCE MOVEMENT (NRM) ............................................................ 5 3. THE CONSTITUTION-MAKING PROCESS: THE RESTORATION OF THE BUGANDA KINGSHIP ....................................................................................................................................................... -

Concise ICOMOS Advisory Mission Report Tombs of Buganda Kings at Kasubi a World Heritage Property of Uganda

Concise ICOMOS Advisory Mission Report Tombs of Buganda Kings at Kasubi A World Heritage property of Uganda Mission undertaken from 12th to 15th May 2014 by: Karel Bakker, architect, ICOMOS University of Pretoria In close collaboration with the Government of Uganda and the Buganda Kingdom CONCISE REPORT ON THE ADVISORY MISSION TO Tombs of Buganda Kings at Kasubi, UGANDA (C 1022) This document is the result of the mission undertaken in Kampala from 12TH to 15th May 2014 Report by: Karel Bakker ICOMOS Department of Architecture, University of Pretoria Tel: +27 83 5640381 email : [email protected] ACKNOWLEDGEMENTS The mission would like to acknowledge the following people who were instrumental in the successful completion of the evaluation mission or providing insight and/or data: The Katikkiro of Baganda HON Charles P Mayiga 2nd Dep Katikkiro OSM Sekimpi Semambo Secretary General of UNATCOM for UNESCO Mr. Augustine Omare-Okurut Project specialist UNATCOM Mr Daniel Kaweesi UNESCO Eastern Africa Regional Office Mr Marc Patry UNESCO Eastern Africa Regional Office Mr Msakazu Shibata ICOMOS Paris Ms Regina Durighello and staff Commissioner for Museums and Monuments Ms Rose Mwanja Site Manager Kasubi Tombs World Heritage Mr Remigius Kigongo Mugerwa Secretary of the Steering Committee Mr Chris Bwanika CRATerre Mr Sebastien Moriset UNESCO-Japanese Technical Expert mission Prof Kazuhiko Nitto and his team Kasubi Tombs World Heritage site The Nalinya and all in residence SUMMARY REPORT AND LIST OF RECOMMENDATIONS Due to lateness of the mission and the need for the recommendations to be available for the 38th Session, UNESCO and ICOMOS have indicated that the mission Report be concise in answering the TORs of the mission directly, rather than following the standard Advisory Mission Report format. -

Kasubi Tombs. Uganda, Kampala S´Ebastienmoriset

Kasubi Tombs. Uganda, Kampala S´ebastienMoriset To cite this version: S´ebastienMoriset. Kasubi Tombs. Uganda, Kampala. CRAterre, 40 p., 2011, 978-2-906901- 68-1. <hal-00837967> HAL Id: hal-00837967 https://hal.archives-ouvertes.fr/hal-00837967 Submitted on 24 Jun 2013 HAL is a multi-disciplinary open access L'archive ouverte pluridisciplinaire HAL, est archive for the deposit and dissemination of sci- destin´eeau d´ep^otet `ala diffusion de documents entific research documents, whether they are pub- scientifiques de niveau recherche, publi´esou non, lished or not. The documents may come from ´emanant des ´etablissements d'enseignement et de teaching and research institutions in France or recherche fran¸caisou ´etrangers,des laboratoires abroad, or from public or private research centers. publics ou priv´es. A WORLD HERITAGE SITE UN SITE DU PATRIMOINE MONDIAL UGANDA - KAMpaLA TabLE OF CONTENTS | TABLE DES MATIÈRES Location 4 Situation géographique Glossary 6 Lexique History and Culture 7 Histoire et Culture The four Kabakas at Kasubi 10 Les quatre Kabakas de Kasubi Site description 14 Description du site Muzibu-Azaala-Mpanga 18 Muzibu-Azaala-Mpanga The March 2010 Tragedy 24 Tragédie du mars 2010 The reconstruction project 26 Le projet de reconstruction The thatched roofs 28 Les toitures en paille Bark cloth 30 Tissus d’écorce Anthropological dimensions 32 Dimensiosn anthropologiques Conservation 35 Conservation Other places of interest 36 Autres richesses à découvrir Other ganda sites 38 Autres sites Ganda Kabaka Ronald Muwenda Kimera Mutebi II UGANDA - KAMpaLA KASUBI TOMBS This booklet, originally printed in 2006 with Ce fascicule, édité une première fois en 2006 avec le the financial support of the French Embassy in soutien de l’ambassade de France à Kampala, a été révisé Kampala, was revised in 2011 to include new en 2011 pour présenter la stratégie de reconstruction elements on the reconstruction strategy. -

49 USAD Music Resource Guide • 2017–2018 • Revised Page

da ancestral forefather Kintu and his wife Nambi.77 is a list of ensembles and solo instruments associat- ed with it. 80 In some traditions he is the first kabaka (king) of Buganda; in others a later individual named Kato- Entamiivu ensemble (six drums and twelve- tationRuhuuga until took the on second Kintu’s half name of the and nineteenth became the centu first- key amadinda xylophone) kabaka. In the absence of relevant written documen- Akadinda (twenty-four-key xylophone) ry, some scholars have estimated generations back. Kawuugulu (set of six drums) Theward oldest and dated of the the royal origins instruments, of the Buganda a pair ofkingdom drums Mujaguzo (drums of kingship) to Kabaka Kintu in the early fourteenth century ce Emibala (praise drums of the king) - that formed the nucleus of the Kawuugulu set, are Amaggunju (dance drums) believed to date back to at least this first king. It78 was Entenga (tuned drum/drum-chime ensem during the reign of the ninth king, Kabaka Mulondo, - ble) that the full six-drum Kawuugulu set emerged. Lyre (endongo) The kingship of Buganda had major repercus Harp (enanga) sions for the modern nation of Uganda. The Uganda andAgreement his chiefs. of 1900 British established administrators British appointed colonial rule Ba- Fiddle (endingidi) and British indirect rule via the kabaka of Buganda Flute (ndere) - Abalere Side-blown trumpet (amakondere) ganda chiefs to govern other areas of Uganda, which gave the Baganda a privileged status. Due to arbi- (flute and drum ensemble) - trary colonial boundaries, Uganda encompasses the Abadongo (fiddle, flute, and lyre ensemble) relatively centralized Bantu kingdoms in the pre In the mid-1960s, just before the palace was at dominantly Christian south, where there is greater- tacked, there were 315 drummers employed by the limurbanization, north. -

White Fathers, Islam and Kiswahili in Nineteenth-Century Uganda

ASIAN AND AFRICAN STUDIES, 73, 2004, 2, 198-213 WHITE FATHERS, ISLAM AND KISWAHILI IN NINETEENTH-CENTURY UGANDA Viera P a w l i k o v á-V il h a n o v á Institute of Oriental and African Studies, Slovak Academy of Sciences, Klemensova 19, 813 64 Bratislava, Slovakia Though present on the East African coast for nearly a thousand years, Islam only began its expansion into the interior in the nineteenth century. One of the most significant areas of Islamic penetration in East and Central Africa was the Kingdom of Buganda, where Islam predated the arrival of Christianity by several decades and secured a strong foothold. Buganda was won to Christianity amidst much turmoil and bitter struggle between the adherents of Islam and of two forms of Christianity, represented by the Anglican Church Missionary Society and Roman Catholic White Fathers, for the dominant position in the kingdom. Despite severe defeats suffered in Buganda in the late 1880s and throughout the 1890s Islam recovered and survived as a minority religion. However, the latent fear of Islam influenced the language policy and mined the prospects of Kiswahili in Uganda. “I have, indeed, undermined Islamism so much here that Mtesa has deter mined henceforth, until he is better informed, to observe the Christian Sabbath as well as the Muslim Sabbath,...” boasted the famous traveller Henry Morton Stanley when describing his visit to the Kingdom of Buganda in April 1875.1 Though present on the East African coast for nearly a thousand years, Islam only began its expansion into the interior in the nineteenth century.2 One of the most significant areas of Islamic penetration in East and Central Africa was the 1 Stanley, H.M.: Through the Dark Continent.