000UGC-JOURNAL-VOL 5, All for Website

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Civil Department, Pulchowk Campus, Institute of Engineering

CIVIL DEPARTMENT, PULCHOWK CAMPUS, INSTITUTE OF ENGINEERING Faculty: Civil Engineering Civil Engineering/Structural Engineering/Environment Engineering/Geotechnical Engineering/Surveying/Water Resources Engineering/Transportation Engineering/ Construction Management/Disaster Risk Management Name: VISHWA NATH KHANAL (Professor/Associate Prof./Lecturer/Chief Instructor/ Senior Instructor/ Instructor/ Dy. Instructor) Recent Photo Existing Position: Professor E - Mail: [email protected] Phone Office: 977 01 5525477 Phone Home: 977 01 4282701 Phone Extension: N/A Education Bachelor’s Degree: B. E. (Civil), Tribhuvan University Master’s Degree: M.Sc. in Construction Management, Pokhara University Diploma/PCL/+2 Degree: Diploma in Civil Engineering, Nepal Engineering Institute, Pulchowk Academic Awards N/A. Research Areas Construction Research Interests Construction Management Employment Record and Academic Responsibilities From To Designation Organization 11.09.2012 date Professor Pulchowk Campus 15.04.2012 10.09.2012 Professor Thapathali Campus 24.10.2005 14.04.2012 Associate Professor Thapathali Campus 09.01.2000 23.10.2005 Lecturer Thapathali Campus 15.04.1995 08.01.2000 Lecturer Pulchowk Campus CIVIL DEPARTMENT, PULCHOWK CAMPUS, INSTITUTE OF ENGINEERING 17.08.1990 14.04.1995 Assistant Lecturer Pulchowk Campus 01.07.1984 16.08.1990 Instructor Pulchowk Campus 17.09.1980 30.06.1984 Assistant Project Engineer IOE, Development Project Administrative Responsibilities From To Responsibilities Organization 22.03.2013 22.03.2015 Head of Department, Department of Pulchowk Campus Civil Engineering, 26.01.2003 26.01.2007 Campus Chief Thapathali Campus 26.03.2001 25.01.2003 Act. Campus Chief Thapathali Campus 16.11.2000 25.03.2001 Asst. Campus Chief Thapathali Campus 09.01.2000 15.11.2000 Head of Department Thapathali Campus 10.04.1996 21.01.1997 Director, Facility Management Unit, Institute of Engineering, Engineering Education Project Pulchowk, Lalitpur 01.11.1993 09.04.1996 Program Officer, Diploma Program, Pulchowk Campus Department of Civil Engineering. -

Information Brochure

Tribhuvan University Institute of Engineering Entrance Examination Board Information Brochure Entrance Examination and Admission Procedure for M.Sc. Programs under IOE IOE Entrance Examination Board-2074 2018(2074) Tribhuvan University Institute of Engineering Entrance Examination Board Detailed Schedule for Entrance Examination of Masters Programs – 2074 Time and Date for Online Application: From 10 AM, 1stFalgun 2073 (13thFebruary 2018) To 5 PM, 15thFalgun 2074 (27thFebruary 2018) Admit card can be downloaded during Falgun17-18, 2074 from the website: http://entrance.ioe.edu.np OR www.ioe.edu.np/entrance Entrance Examination will be held at ICTC, IOE, Pulchowk: 19-20 Falgun2074 (March3-4, 2018) Publication of Result:By 25thof Falgun, 2074 (By 9thMarch, 2018) To be eligible for master’s entrance application, the candidate must have passed bachelor degree in relevant subjects with at least second division. Admission Notice for the successful candidates shall be published by the Admission Committee of Constituent Campuses of IOE. The Academic session starts from 16thBaisakh 2075 (29thApril, 2018) lq=lj= OlGhlgol/Ë cWoog ;+:yfgåf/f z}lIfs aif{ @)&$÷)&% df ;+rfng ul/g] :gftsf]Q/ txsf] k|a]z k/LIff ptL0f{ ug{] k/LIffyL{x? g]kfn ;/sf/, lzIff dGqfnosf] 5fqa[lQ ;DaGwL lgodfjnL cg';f/ tf]lsPsf] sfg'gL dfkb08 k'/f u/]df ;f] dGqfnoåf/f @)&$÷)&% df k|bfg ul/g] :gftsf]Q/ txsf pRr lzIffsf 5fqa[lQx?sf nflu ;d]t pDd]bjf/ x'g of]Uo x'g]5g\ . 1 INTRODUCTION 1.1 History of IOE History of engineering education in Nepal can be traced to 1942 AD, when Technical Training School was established. -

Rabin Dhakal Citizenship: Nepal Date of Birth

Rabin Dhakal Citizenship: Nepal Date of Birth: 1991 March 21 Current Address US: 1001 University Ave, Apt 3107, Lubbock, TX 79401 Tel: +1(806) 401-2642 (mob) Email: [email protected], [email protected] Website: https://rabindhakal.com/ EDUCATION Ongoing : Phd in Mechanical Engineering, Texas Tech University 2014 : Bachelor’s Degree in mechanical engineering, Tribhuvan University, Institute of Engineering, Pulchowk Campus 2009 : Diploma in Mechanical Engineering, Tribhuvan University, Institute of Engineering, Thapathali Campus PROFESSIONAL EXPERIENCE 08/2019- now Teaching Assistant (part time as PhD student) Department of Mechanical Engineering, Texas Tech University, TX, USA 07/2018-07/2019 Teaching Faculty (full time) Department of Mechanical Engineering, Kathmandu University, Nepal 09/2014-07/2018 Lecturer (full time) Department of Engineering, Science and Humanities, Kantipur Engineering College, Tribhuvan University, Nepal 2014- 2017 Teaching Assistant (part time) Mechanical and Automobile Department, Thapathali Campus, Institute of Engineering, Tribhuvan University, Nepal 2014- 2019 Freelance Consultant/Consultant, Vortex Energy Solution Pvt. Ltd (part time) Vortex Energy Solution is Rabin’s own private energy research and consulting firm. HONORS and AWARDS 2017 Best Paper Award, IEEE International Conference on Renewable Energy Research and Application 2017, 5-8 Nov, San Diego, USA 2015 Best Practice Award, 11 th International Conference “ASIAN Community Knowledge Networks for the Economy, Society, Culture, and Environmental -

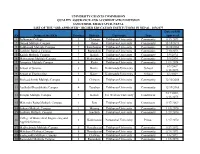

SSR Approved Heis

UNIVERSITY GRANTS COMMISSION QUALITY ASSURANCE AND ACCREDITATION DIVISION SANOTHIMI, BHAKTAPUR, NEPAL LIST OF THE "SSR APPROVED" HIGHER EDUCATION INSTITUTIONS IN NEPAL, 2076/077 Date of SSR SN Name of the HEIs Province District University Type Approved 1 Balkumari College 3 Chitwan Tribhuvan University Community 5/19/2073 2 Damak Multiple Campus 1 Jhapa Tribhuvan University Community 11/15/2073 3 Siddhanath Multiple Campus 7 Kanchanpur Tribhuvan University Community 12/26/2066 4 Lumbini Banijya Campus 5 Rupandehi Tribhuvan University Community 7/10/2073 5 Kailali Multiple Campus 7 Kailali Tribhuvan University Community 3/9/2074 6 Makwanpur Multiple Campus 3 Makwanpur Tribhuvan University Community 3/9/2074 7 Janapriya Multiple Campus 4 Kaski Tribhuvan University Community 11/3/2074 6/1/2069 8 School of Science 3 Kavre Kathmandu University School 3/13/2075 9 School of Engineering 3 Kavre Kathmandu University School 6/1/2069 10 Shaheed Smriti Multiple Campus 3 Chitwan Tribhuvan University Community 12/10/2068 11 Aadikabi Bhanubhakta Campus 4 Tanahun Tribhuvan University Community 12/10/2068 9/17/2069, 12 Tikapur Multiple Campus 7 Kailali Far-Western University Constituent 3/13/2075 13 Mahendra Ratna Multiple Campus 1 Ilam Tribhuvan University Constituent 9/17/2069 14 Sukuna Multiple Campus 1 Morang Tribhuvan University Community 11/5/2070 15 Sindhuli Multiple Campus 3 Sindhuli Tribhuvan University Community 1/27/2070 College of Biomedical Engineering and 16 3 Kathmandu Purbanchal University Private 1/27/2070 Applied Sciences 17 Madhyabindu -

QAA Annual Report 2075/76

HEQAAC 68 Annual Report 2075/076 (2018/019) HIGHER EDUCATION QUALITY ASSURANCE AND ACCREDITATION COUNCIL ANNUAL REPORT 2075/076 (2018/019) UNIVERSITY GRANTS COMMISSION QUALITY ASSURANCE AND ACCREDITATION DIVISION SANOTHIMI, BHAKTAPUR, NEPAL HEQAAC 2075/076 (2018/019) Annual Report 69 ANNUAL REPORT OF HIGHER EDUCATION QUALITY ASSURANCE AND ACCREDITATION COUNCIL, 2075/076 Copyright © : University Grants Commission, Quality Assurance & Accreditation Council, Sanothimi, Bhaktapur, Nepal Edition : December 2019 (Second) Printed Copies : 500 Layout : Digital Print Nepal, 014332600 Printed at : HEQAAC 70 Annual Report 2075/076 (2018/019) FROM THE DESK OF THE CHAIRMAN igher education is the backbone of development and the future of a nation. Its primary aim is to Hproduce qualified, creative and competitive citizens nationally, regionally and globally. To achieve this aim, governments are making their best efforts through introducing various policies, acts, rules and guidelines and by establishing necessary institutions to manage the system. In Nepal, the University Grants Commission (UGC) was established in 2050 BS (1993 AD) as an apex institution to provide grants and coordinate regulate activities related to higher education. Education policies provide road map to the prosperity of the nation and over the last seven decades i.e., since 1950 the country has also implemented at least eight progressive education policies of Nepal and the ‘National Education Policy 2076’ is the latest one. At present, Nepal has 11 operating Universities, six health-science Academies and 1425 higher education institutions (HEIs) under these universities and academies. More than a hundred HEIs are offering academic programs of foreign universities as well. However, the enrolment rate in higher education is quite low (i.e. -

Programme Schedule for Pulchowk Campus (PDF: 104KB)

Seminar on Higher Education Opportunities in Japan Programme Schedule for Pulchowk Campus Date: November- 24, Sunday, 2019. Time: 15.45 PM to 18.30 PM Venue: F - Hall, Civil Department, Pulchowk Campus, Institute of Engineering, Tribhuvan University. Hosted by The University of Tokyo (UTokyo) appointed for Study in Japan Global Network Project in South West Asia by the Ministry of Education, Culture, Sports, Science and Technology (MEXT) and supported by UTokyo Alumni Association of Nepal (UTAAN) and Pulchowk Campus (PC), Institute of Engineering, Tribhuvan University. Program Details SN Program Assigned Time (minutes) Remarks 1 Registration Dr Chalise 15.45-16.00 2 Welcome Remarks Dr Raghunath Jha 16.00-16.05 Host Institution, PC 3 Opening remarks and introduction Mr Ram Bhandari 16.05-16.15 UTAAN - of Japanese delegates Chairperson 4 MEXT Scholarship opportunities Dr Yuriko 16.15-16.27 The Embassy of in Japan Akiyama Japan in Nepal 5 Presentation from Japan Science Mr Kazuhiko Aoki 16.27-16.39 JST and Technology Agency (JST) 6 Presentation from Ehime Prof Netra Prakash 16.39-16.51 Ehime University Bhandary University 7 Presentation from Saitama Mr Goit Chandra 16.51-17.03 Saitama University University Shekhar 8 Presentation from The University Prof Tatsuki 17.03-17.15 The University of of Aizu Kawaguchi; Mr Aizu Shashank Shrestha 9 Experience of Higher Education in Mr Khem Gyawali 17.15-17.27 UTokyo Japan 10 Question & Answer 17.27-17.50 11 Closing Remarks & Way Forward 17.50-17.55 UTokyo 12 Individual consultation /Interaction 17.55 -18.20 M/C : from PC Japanese Delegates Time Schedule Arrival to PEC: 15.15 AM Preparation and set up for the presentation: 15.15-15.30 Meeting with IOE, Authorities : 15.30-15.45 Members of Japanese Delegates 1. -

Tribhuvan University Institute of Engineering Pulchowk Campus

TRIBHUVAN UNIVERSITY INSTITUTE OF ENGINEERING PULCHOWK CAMPUS STRATEGIC PLAN (2017-2021) KATHMANDU, 2018 CONTENTS SECTION 1 ................................................................................................................................... 1 INTRODUCTION ........................................................................................................................ 1 1.1 Contexts and Rationale of Strategic Plan .......................................................................................... 1 1.2 Purpose of the Plan ........................................................................................................................... 1 1.3 Process of Preparing the Plan ........................................................................................................... 2 1.4 Participants of Strategic Planning ..................................................................................................... 2 1.5 Stakeholders ...................................................................................................................................... 2 1.6 Components of the Strategic Plan .................................................................................................... 3 1.6.1. Academic Excellence ................................................................................................................. 3 1.6.2 Think‐Tank .................................................................................................................................. 5 1.6.3 -

ENGIEERING Web2071-2072.Pdf

lghfdtL sd{rf/L ;Gtlt 5fqj[lQ )&!÷)&@ df 5gf}6 ePsf ljBfyL{x?sf] ljj/0f ljifoM Ol~hlgol/ª (ENGINEERING) hDdf l;6 ;+VofM !%$ v'nftkm{ M *%+& -blnt %, ckfª\utf ePsf JolQm @ l;6 yk ul/Psf]_ cfj]bg lbg] hDdf pDd]bjf/M @^^ kb÷;]jf÷>]0f cWoog/t lzIf0f ;+:yfsf] gfd, 7]ufgf ;+s]t g+== laifo ljBfyL{sf] gfd sd{rf/Lsf] gfd, y/ sd{rf/Lsf] sfof{no egf{ jif{ lnË l;=g+= btf{ g+= L ;Dks{ g+=/ Od]n cf}ift k|fKtfª 1 68 sf}/a uf}td b]jL k|;fb uf}td lhNnf jg sfof{no, dsjfgk'/, x]6f}+8f jg /Ifs ENGINEERING 2071 Thapathali Campus, Thapathali M 88.86 2 399 gljg cfrfo{ gf/fo0f k|;fb cfrfo{ ,710873 vfg]kfgL tyf ;/;kmfO{ l8lehg l;=l8=O{= ENGINEERING 2071 Kathmandu Engineering College, M 87.67 sfof{no, uf]/vf Kalimati 3 424 ?s'df zdf{ /fh]Gb| k|;fb zdf{ ,156150 l;+rfO ljefu, nlntk'/ l;=l8=O{= ENGINEERING 2071 Central Campus, Pulchowk F 87.58 4 352 >j0f lbk uf}td tLy{ /fh uf}td ,159396 lhNnf :jf:Yo sfof{no, d+un;]g, tYof+s ENGINEERING 2071 Tribhuvan University Institute of M 87.36 c5fd clws[t Engineering Central Campus Pulchowk, Lalitpur 5 14 k|zfGt bfxfn e"k/fh bfxfn ,118796 lhNnf ljsf; ;ldltsf] sfof{no, uf=lj=;=;lrj ENGINEERING 2071 Central Campus, Pulchowk M 86.60 nlntk'/ -zf=c_ Page 1 6 322 ldng e§/fO{ gf/fo0f k|;fb e§/fO{ ,117879 klZrdf~rn l;+rfO ljsf; l8lehg g+ sfof{no ENGINEERING 2071 TU Institute of Engineering M 86.53 ^, ?kGb]xL ;xof]uL Pashchimanchal Campus, Pokhara 7 414 k|zfGt sfsL{ s]bf/ sfsL{ ,140566 >L dWodf~rn If]qLo x'nfs n]vf clws[t ENGINEERING 2071 Central Campus, Pulchowk M 86.48 lgb]{zgfno, aa/dxn § 8 519 k|Hjn e /fO{ dfwj k|;fb e§/fO{ ,154760 -

1.1A Epigraphy of Inauguration of Thapathali Campus

Institute of Engineering Thapathali Campus Thapathali, Kathmandu 1.A(6).1.1a Epigraphy of inauguration of Thapathali campus Inauguration by Late King Mahendra B.B. Shah and German Chancellor Dr.Heinrich Lubke 1.A(6).1.1 Approval of B.E. and M.Sc. Class in thapathali campus 1 Self Study ANNEX For QAA Institute of Engineering Thapathali Campus Thapathali, Kathmandu Approval of BE industrial Engineering Approval of M.Sc. Earth Quake 2 Self Study ANNEX For QAA Institute of Engineering Thapathali Campus Thapathali, Kathmandu 1.2 3 Self Study ANNEX For QAA Institute of Engineering Thapathali Campus Thapathali, Kathmandu 2.A(9).1.1 LAND OWNERSHIP CERTIFICATE of thapathali campus,thapathali 4 Self Study ANNEX For QAA Institute of Engineering Thapathali Campus Thapathali, Kathmandu 1.A(9).1.2 5 Self Study ANNEX For QAA Institute of Engineering Thapathali Campus Thapathali, Kathmandu 1.3 6 Self Study ANNEX For QAA Institute of Engineering Thapathali Campus Thapathali, Kathmandu 3.A(10).1.1 Llocation map of Thapathali Campus 1.2 Schematic internal infrastructure of Thapathali Campus 7 Self Study ANNEX For QAA Institute of Engineering Thapathali Campus Thapathali, Kathmandu 4.A(11).1.1 Brochure of Thapathali Campus 2075 (English Version) 5.A (14)1.1 Recruitment of teaching and non-teaching staff 8 Self Study ANNEX For QAA Institute of Engineering Thapathali Campus Thapathali, Kathmandu 1.1 The rules of recruitment for permanent from red book of TU 1.2 The rules of recruitment for permanent from red book of TU 9 Self Study ANNEX For QAA Institute -

Institute of Engineering Entrance Examination Board

Tribhuvan University Institute of Engineering Entrance Examination Board Information Brochure on Entrance Examination and Admission for M.Sc. Programs at Pulchowk Campus 2068 0 /17 Tribhuvan University Institute of Engineering Entrance Examination Board Detailed Schedule for Entrance Examination of Masters Programs ‐ 2068. Time and Date for online application : From 8 AM, 26th Bhadra 2068 (12th September 2011) To 8 PM, 8th Ashwin 2068 (25th Septemer 2011) Admit Card Distribution at Pulchowk Campus: Normal Schedule : From 11:00 AM to 3:00 PM 26th & 27th of Ashwin 2068 (13th & 14th October 2011) With 2000/- extra charge : From 11:00 AM to 3:00 PM of 29th Ashwin 2068 (16th October 2011) Entrance Examination at Pulchowk Campus: From 7:00 AM to 10:00 AM, 1st Kartik 2068 (18th October 2011). Publication of Result 5th of Kartik 2068 (22nd October 2068) Score Card Distribution at Pulchowk Campus: From 11:00AM to 3:00 PM, 7th and 8th of Kartik 2068 (24th & 25th October 2011) Notice for the Admission shall be published by Pulchowk Campus Admission Committee. The Academic session starts from 1st Mangsir 2068 (17 November 2011). 1 /17 1. INTRODUCTION 1.1 History of IOE History of engineering education in Nepal can be traced since 1942, when Technical Training School was established. Engineering section of the school offered only trades and civil sub- overseers programs. In 1959, Nepal Engineering Institute, with the assistance of the government of India, started offering civil overseer courses leading to Diploma in Civil Engineering. The Technical Training Institute established in 1965, with the assistance from the Government of Federal Republic of Germany, offered technician courses in General courses in General Mechanics, Auto Mechanics, Electrical Engineering and Mechanical Drafting. -

Thapathali Campus Degree Bachelor of Engineering Examination: 2073 (B .E./8

·' http://edunepal.info/ioe/thapathali ~ ·.r.~ Date : 2073/5/20 ..,. ·"'·\. ~ ~c• · . · :;•. \ . ,f Tribhuvan University ·,. , , r~ ("' r: · c§~..,_,-.,,~ Institute Of Engineering ~~r~,:-; ;· 1J .\ ~~ c~~fi rs t Admission List Campus: Thapathali Campus Degree Bachelor Of Engineering Examination: 2073 (B .E./8. A rch. Entrance Examination) Field of study: Civil Engineering (Regular) (1) Pirority EntranceS Entrance S.No App.No. FuiiName Sex Exam Ro iiNo Pl P2 P3 P4 P7 P8 PlS P16 P19 P20 core Rank Remarks 1. 137 Rakesh Kumar Pand it M 2073-1098 1 77.214 132 2 60 Gu njan Bastola M 2073-4855 1 . 7 77.214 133 3 971 Shi raj an Raj Bajaracharya M 2073-4784 1 19 75.714 159 4 1021_ Rupesh Kumar Limbu M .2073-6587 1 75.000 180 5 16 . Saubhagya B. C M 2073-3833 1 74.857 185 6 360 Gautam Cha urasia M 2073-3743 1 74.857 192 7 946 Pasang Chhiring Sherpa M 2073-4146 1 74.857 198 8 1038 Shash ank Adhikari M 2073-1279 1 2 74.071 204 9 820 Prat ik Babu Pokharel M 2073-2956 1 2 74.071 211 10 769 Rabin Lamichhane M 2073-3893 1 2 73.857 219 11 1034 Su nil Thapa M 2073-6355 1 7 73.429 223 12 1215 Gyanendra Bikram Ghimire M 2073-2331 1 73.286 225 t--· 13 303 Shwet a Sa h F 2073-2296 1 73.286 231 14 973 Yuvaraj Timalsina M 2073-3160 1 73 .286 237 15 411 Sandeep Acharya M 2073-534 1 73.286 238 16 622 Aman Jaiswal M 2073-8916 1 19 7 73.286 244 17 508 Saroj Paudel M 2073-5552 1 72.571 249 18 731 Ravi Ranjan Kumar Mishra M 2073-414 1 72.500 25 1 19 550 Ankit Giri M 2073-5596 1 72.500 254 .., 20 1046 Sarad Lamsal M 2073-4301 . -

Tribhuvan University Institute of Engineering Thapathali Campus

TRIBHUVAN UNIVERSITY INSTITUTE OF ENGINEERING THAPATHALI CAMPUS FINAL YEAR PROJECT REPORT ON INTELLIGENT TRANSPORTATION SYSTEM BY: Anita Maharjan (72851) Laxmi KC (72868) Rasmi Wagle (72876) Rasu Shrestha (72877) SUBMITTED TO: DEPARTMENT OF ELECTRONICS AND COMPUTER ENGINEERING INSTITUTE OF ENGINEERING THAPATHALI CAMPUS KATHMANDU, NEPAL Bhadra, 2071 TRIBHUVAN UNIVERSITY INSTITUTE OF ENGINEERING THAPATHALI CAMPUS FINAL YEAR PROJECT REPORT ON INTELLIGENT TRANSPORTATION SYSTEM BY: Anita Maharjan (72851) Laxmi KC (72868) Rasmi Wagle (72876) Rasu Shrestha (72877) THIS PROJECT WAS SUBMITTED TO THE DEPARTMENT OF ELECTRONICS AND COMPUTER ENGINEERING, IOE, THAPATHALI CAMPUS IN PARTIAL FULLFILLMENT OF THE REQUIREMENT FOR THE BACHELOR’S DEGREE IN ELECTRONICS AND COMMUNICATION ENGINEERING DEPARTMENT OF ELECTRONICS AND COMPUTER ENGINEERING INSTITUTE OF ENGINEERING THAPATHALI CAMPUS KATHMANDU, NEPAL Bhadra, 2071 DEPARTMENT ACCEPTANCE The project titled “Intelligent Transportation System” submitted by Anita Maharjan, Laxmi KC, Rasmi Wagle and Rasu Shrestha in partial fulfillment of the requirement for Bachelor’s Degree in Electronics and Communication Engineering has been accepted as a bona-fide record of work carried out by them for our department. _____________________ Er. Janardan Bhatta Head of Department Department of Electronics and Computer Engineering Institute of Engineering, Thapathali Campus Kathmandu, Nepal i CERTIFICATE OF APPROVAL The undersigned certify that they have read and recommended to the Department of Electronics and Computer Engineering, Institute of Engineering, Thapathali Campus, a final project work titled “Intelligent Transportation System” submitted by Anita Maharjan, Laxmi KC, Rasmi Wagle and Rasu Shrestha in partial fulfillment of the requirement for Bachelor’s Degree in Electronics and Communication Engineering. ___________________ ___________________ Project Supervisor External Examiner Er. Prasanna Kansakar Prof.