Minilap: a MIGS Approach to the Benign Large Adnexal Mass Surgical Technique Video

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Neurokinin Receptor NK Receptor

Neurokinin Receptor NK receptor There are three main classes of neurokinin receptors: NK1R (the substance P preferring receptor), NK2R, and NK3R. These tachykinin receptors belong to the class I (rhodopsin-like) G-protein coupled receptor (GPCR) family. The various tachykinins have different binding affinities to the neurokinin receptors: NK1R, NK2R, and NK3R. These neurokinin receptors are in the superfamily of transmembrane G-protein coupled receptors (GPCR) and contain seven transmembrane loops. Neurokinin-1 receptor interacts with the Gαq-protein and induces activation of phospholipase C followed by production of inositol triphosphate (IP3) leading to elevation of intracellular calcium as a second messenger. Further, cyclic AMP (cAMP) is stimulated by NK1R coupled to the Gαs-protein. The neurokinin receptors are expressed on many cell types and tissues. www.MedChemExpress.com 1 Neurokinin Receptor Antagonists, Agonists, Inhibitors, Modulators & Activators Aprepitant Befetupitant (MK-0869; MK-869; L-754030) Cat. No.: HY-10052 (Ro67-5930) Cat. No.: HY-19670 Aprepitant (MK-0869) is a selective and Befetupitant is a high-affinity, nonpeptide, high-affinity neurokinin 1 receptor antagonist competitive tachykinin 1 receptor (NK1R) with a Kd of 86 pM. antagonist. Purity: 99.67% Purity: >98% Clinical Data: Launched Clinical Data: No Development Reported Size: 10 mM × 1 mL, 5 mg, 10 mg, 50 mg, 100 mg, 200 mg Size: 1 mg, 5 mg Biotin-Substance P Casopitant mesylate Cat. No.: HY-P2546 (GW679769B) Cat. No.: HY-14405A Biotin-Substance P is the biotin tagged Substance Casopitant mesylate (GW679769B) is a potent, P. Substance P (Neurokinin P) is a neuropeptide, selective, brain permeable and orally active acting as a neurotransmitter and as a neurokinin 1 (NK1) receptor antagonist. -

Stembook 2018.Pdf

The use of stems in the selection of International Nonproprietary Names (INN) for pharmaceutical substances FORMER DOCUMENT NUMBER: WHO/PHARM S/NOM 15 WHO/EMP/RHT/TSN/2018.1 © World Health Organization 2018 Some rights reserved. This work is available under the Creative Commons Attribution-NonCommercial-ShareAlike 3.0 IGO licence (CC BY-NC-SA 3.0 IGO; https://creativecommons.org/licenses/by-nc-sa/3.0/igo). Under the terms of this licence, you may copy, redistribute and adapt the work for non-commercial purposes, provided the work is appropriately cited, as indicated below. In any use of this work, there should be no suggestion that WHO endorses any specific organization, products or services. The use of the WHO logo is not permitted. If you adapt the work, then you must license your work under the same or equivalent Creative Commons licence. If you create a translation of this work, you should add the following disclaimer along with the suggested citation: “This translation was not created by the World Health Organization (WHO). WHO is not responsible for the content or accuracy of this translation. The original English edition shall be the binding and authentic edition”. Any mediation relating to disputes arising under the licence shall be conducted in accordance with the mediation rules of the World Intellectual Property Organization. Suggested citation. The use of stems in the selection of International Nonproprietary Names (INN) for pharmaceutical substances. Geneva: World Health Organization; 2018 (WHO/EMP/RHT/TSN/2018.1). Licence: CC BY-NC-SA 3.0 IGO. Cataloguing-in-Publication (CIP) data. -

Acer Therapeutics Inc. Form 8-K Current Event Report Filed 2021-06

SECURITIES AND EXCHANGE COMMISSION FORM 8-K Current report filing Filing Date: 2021-06-17 | Period of Report: 2021-06-17 SEC Accession No. 0001564590-21-033350 (HTML Version on secdatabase.com) FILER Acer Therapeutics Inc. Mailing Address Business Address ONE GATEWAY CENTER ONE GATEWAY CENTER CIK:1069308| IRS No.: 320426967 | State of Incorp.:DE | Fiscal Year End: 1231 (300 WASHINGTON ST.) (300 WASHINGTON ST.) Type: 8-K | Act: 34 | File No.: 001-33004 | Film No.: 211024741 SUITE 351 SUITE 351 SIC: 2834 Pharmaceutical preparations NEWTON MA 02458 NEWTON MA 02458 (844) 902-6100 Copyright © 2021 www.secdatabase.com. All Rights Reserved. Please Consider the Environment Before Printing This Document UNITED STATES SECURITIES AND EXCHANGE COMMISSION WASHINGTON, D.C. 20549 FORM 8-K CURRENT REPORT Pursuant to Section 13 or 15(d) of the Securities Exchange Act of 1934 Date of Report (date of earliest event reported): June 17, 2021 ACER THERAPEUTICS INC. (Exact name of registrant as specified in its charter) Delaware 001-33004 32-0426967 (State or other jurisdiction of (Commission File Number) (IRS Employer Identification No.) incorporation) One Gateway Center, Suite 351 300 Washington Street Newton, Massachusetts 02458 (Address of principal executive offices) (Zip Code) Registrant’s telephone number, including area code: (844) 902-6100 N/A (Former name or former address, if changed since last report) Check the appropriate box below if the Form 8-K filing is intended to simultaneously satisfy the filing obligation of the registrant under any of -

WHO-EMP-RHT-TSN-2018.1-Eng.Pdf

WHO/EMP/RHT/TSN/2018.1 The use of stems in the selection of International Nonproprietary Names (INN) for pharmaceutical substances FORMER DOCUMENT NUMBER: WHO/PHARM S/NOM 15 WHO/EMP/RHT/TSN/2018.1 © World Health Organization [2018] Some rights reserved. This work is available under the Creative Commons Attribution-NonCommercial-ShareAlike 3.0 IGO licence (CC BY-NC-SA 3.0 IGO; https://creativecommons.org/licenses/by-nc-sa/3.0/igo). Under the terms of this licence, you may copy, redistribute and adapt the work for non-commercial purposes, provided the work is appropriately cited, as indicated below. In any use of this work, there should be no suggestion that WHO endorses any specific organization, products or services. The use of the WHO logo is not permitted. If you adapt the work, then you must license your work under the same or equivalent Creative Commons licence. If you create a translation of this work, you should add the following disclaimer along with the suggested citation: “This translation was not created by the World Health Organization (WHO). WHO is not responsible for the content or accuracy of this translation. The original English edition shall be the binding and authentic edition”. Any mediation relating to disputes arising under the licence shall be conducted in accordance with the mediation rules of the World Intellectual Property Organization. Suggested citation. The use of stems in the selection of International Nonproprietary Names (INN) for pharmaceutical substances. Geneva: World Health Organization; 2018 (WHO/EMP/RHT/TSN/2018.1). Licence: CC BY-NC-SA 3.0 IGO. -

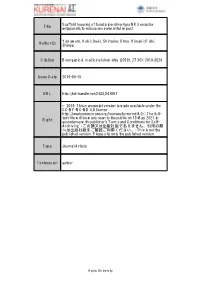

Title Scaffold Hopping of Fused Piperidine-Type NK3 Receptor

Scaffold hopping of fused piperidine-type NK3 receptor Title antagonists to reduce environmental impact Yamamoto, Koki; Inuki, Shinsuke; Ohno, Hiroaki; Oishi, Author(s) Shinya Citation Bioorganic & medicinal chemistry (2019), 27(10): 2019-2026 Issue Date 2019-05-15 URL http://hdl.handle.net/2433/241057 © 2019. This manuscript version is made available under the CC-BY-NC-ND 4.0 license http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by-nc-nd/4.0/.; The full- text file will be made open to the public on 15 May 2021 in Right accordance with publisher's 'Terms and Conditions for Self- Archiving'.; この論文は出版社版でありません。引用の際 には出版社版をご確認ご利用ください。; This is not the published version. Please cite only the published version. Type Journal Article Textversion author Kyoto University Scaffold hopping of fused piperidine-type NK3 receptor antagonists to reduce environmental impact Koki Yamamoto, Shinsuke Inuki, Hiroaki Ohno, Shinya Oishi* Graduate School of Pharmaceutical Sciences, Kyoto University, Sakyo-ku, Kyoto 606-8501, Japan *Corresponding Author: Shinya Oishi, Ph.D. Graduate School of Pharmaceutical Sciences Kyoto University Sakyo-ku, Kyoto, 606-8501, Japan Tel.: +81-75-753-4561; Fax: +81-75-753-4570, E-mail: [email protected] ABSTRACT Neurokinin-3 receptor (NK3R) plays a pivotal role in the release of gonadotropin-releasing hormone in the hypothalamus–pituitary–gonadal (HPG) axis. To develop novel NK3R antagonists with less environmental toxicity, a series of heterocyclic scaffolds for the triazolopiperazine substructure in an NK3R antagonist fezolinetant were designed and synthesized. An isoxazolo[3,4-c]piperidine derivative exhibited moderate NK3R antagonistic activity and favorable properties that were decomposable under environmental conditions. -

OCTOBER 2019 Mrx Pipeline a View Into Upcoming Specialty and Traditional Drugs TABLE of CONTENTS

OCTOBER 2019 MRx Pipeline A view into upcoming specialty and traditional drugs TABLE OF CONTENTS EDITORIAL STAFF Introduction Maryam Tabatabai, PharmD Editor in Chief Senior Director, Drug Information Pipeline Deep Dive Carole Kerzic, RPh Executive Editor Drug Information Pharmacist Keep on Your Radar Consultant Panel Michelle Booth, PharmD Director, Medical Pharmacy Strategy Becky Borgert, PharmD, BCOP Pipeline Drug List Director, Clinical Oncology Product Development Lara Frick, PharmD, BCPS, BCPP Drug Information Pharmacist Glossary Robert Greer, RPh, BCOP Senior Director, Clinical Strategy and Programs Sam Leo, PharmD Director, Clinical Strategy and Innovation, Specialty Troy Phelps Senior Director, COAR - Analytics Nothing herein is or shall be construed as a promise or representation regarding past or future events and Magellan Rx Management expressly disclaims any and all liability relating to the use of or reliance on the information contained in this presentation. The information contained in this publication is intended for educational purposes only and should not be considered clinical, financial, or legal advice. By receipt of this publication, each recipient agrees that the information contained herein will be kept confidential and that the information will not be photocopied, reproduced, distributed to, or disclosed to others at any time without the prior written consent of Magellan Rx Management. 1 | magellanrx.com INTRODUCTION Welcome to the MRx Pipeline. In its third year of publication, this quarterly report offers clinical insights and competitive intelligence on anticipated drugs in development. Our universal forecast addresses trends applicable across market segments. Traditional and specialty drugs, agents under the pharmacy and medical benefits, new molecular entities, pertinent new and expanded indications for existing medications, and biosimilars are profiled in the report. -

Fezolinetant: a Novel Approach for Targeted Menopausal Symptom Relief

ASTELLAS INVESTOR MEETING fezolinetant: A Novel Approach for Targeted Menopausal Symptom Relief December 14, 2017 CAUTIONARY STATEMENT REGARDING FORWARD-LOOKING 2 INFORMATION In this material, statements made with respect to current plans, estimates, strategies and beliefs and other statements that are not historical facts are forward-looking statements about the future performance of Astellas Pharma. These statements are based on management’s current assumptions and beliefs in light of the information currently available to it and involve known and unknown risks and uncertainties. A number of factors could cause actual results to differ materially from those discussed in the forward-looking statements. Such factors include, but are not limited to: (i) changes in general economic conditions and in laws and regulations, relating to pharmaceutical markets, (ii) currency exchange rate fluctuations, (iii) delays in new product launches, (iv) the inability of Astellas to market existing and new products effectively, (v) the inability of Astellas to continue to effectively research and develop products accepted by customers in highly competitive markets, and (vi) infringements of Astellas’ intellectual property rights by third parties. Information about pharmaceutical products (including products currently in development) which is included in this material is not intended to constitute an advertisement or medical advice. AGENDA 3 VMS and fezolinetant I Graeme Fraser, PhD Market Overview II Jeffrey Kern Questions & Answers III B. Zeiher, G. Fraser, J. Kern VMS AND FEZOLINETANT Graeme Fraser, PhD Chief Scientific Officer Ogeda SA MECHANISM OF VASOMOTOR SYMPTOMS (VMS) 5 • Vasomotor symptoms, typically comprised of hot flashes and night sweats, are associated with decreases in reproductive hormones commonly associated with menopause (eg. -

Edinburgh Research Explorer

Edinburgh Research Explorer Effects of NT-814, a dual neurokinin 1 and 3 receptor antagonist, on vasomotor symptoms in postmenopausal women: a placebo- controlled, randomized controlled trial Citation for published version: Trower, M, Anderson, R, Ballantyne, E, Joffe, H, Kerr, M & Pawsey, S 2020, 'Effects of NT-814, a dual neurokinin 1 and 3 receptor antagonist, on vasomotor symptoms in postmenopausal women: a placebo- controlled, randomized controlled trial', Menopause. https://doi.org/10.1097/GME.0000000000001500 Digital Object Identifier (DOI): 10.1097/GME.0000000000001500 Link: Link to publication record in Edinburgh Research Explorer Document Version: Publisher's PDF, also known as Version of record Published In: Menopause General rights Copyright for the publications made accessible via the Edinburgh Research Explorer is retained by the author(s) and / or other copyright owners and it is a condition of accessing these publications that users recognise and abide by the legal requirements associated with these rights. Take down policy The University of Edinburgh has made every reasonable effort to ensure that Edinburgh Research Explorer content complies with UK legislation. If you believe that the public display of this file breaches copyright please contact [email protected] providing details, and we will remove access to the work immediately and investigate your claim. Download date: 27. Sep. 2021 Menopause: The Journal of The North American Menopause Society Vol. 27, No. 5, pp. 498-505 DOI: 10.1097/GME.0000000000001500 ß 2020 The Author(s). Published by Wolters Kluwer Health, Inc. on behalf of The North American Menopause Society. ORIGINAL STUDY Effects of NT-814, a dual neurokinin 1 and 3 receptor antagonist, on vasomotor symptoms in postmenopausal women: a placebo-controlled, randomized trial Mike Trower, PhD,1 Richard A. -

Non-Confidential Corporate Presentation

Developing Therapeutics for the Treatment of Serious Rare and Life-Threatening Diseases with Significant Unmet Medical Needs Corporate Presentation August 2020 Nasdaq: ACER Forward-looking Statements This presentation contains “forward-looking statements” that involve substantial risks and uncertainties for purposes of the safe harbor provided by the Private Securities Litigation Reform Act of 1995. All statements, other than statements of historical facts, included in this presentation regarding strategy, future operations, timelines, future financial position, future revenues, projected expenses, regulatory submissions, actions or approvals, cash position, liquidity, prospects, plans and objectives of management are forward-looking statements. Examples of such statements include, but are not limited to, statements relating to expectations regarding our capital resources; the potential for emetine, ACER-001, EDSIVO™ (celiprolol) and osanetant to safely and effectively treat diseases and to be approved for marketing; the commercial or market opportunity of any of our product candidates in any target indication and any territory; the adequacy of our capital to support our future operations and our ability to successfully initiate and complete clinical trials and regulatory submissions; our progress toward possible approval for EDSIVO™ in light of the Complete Response Letter we received June 2019 and the Formal Dispute Resolution Request response letter received March 2020; the ability to protect our intellectual property rights; our strategy and business focus; and the development, expected timeline and commercial potential of any of our product candidates. We may not actually achieve the plans, carry out the intentions or meet the expectations or projections disclosed in the forward-looking statements and you should not place undue reliance on these forward-looking statements. -

Lääkeaineiden Yleisnimet (INN-Nimet) 31.12.2019

Lääkealan turvallisuus- ja kehittämiskeskus Säkerhets- och utvecklingscentret för läkemedelsområdet Finnish Medicines Agency Lääkeaineiden yleisnimet (INN-nimet) 31.12. -

Neurokinin Receptor NK Receptor

Neurokinin Receptor NK receptor There are three main classes of neurokinin receptors: NK1R (the substance P preferring receptor), NK2R, and NK3R. These tachykinin receptors belong to the class I (rhodopsin-like) G-protein coupled receptor (GPCR) family. The various tachykinins have different binding affinities to the neurokinin receptors: NK1R, NK2R, and NK3R. These neurokinin receptors are in the superfamily of transmembrane G-protein coupled receptors (GPCR) and contain seven transmembrane loops. Neurokinin-1 receptor interacts with the Gαq-protein and induces activation of phospholipase C followed by production of inositol triphosphate (IP3) leading to elevation of intracellular calcium as a second messenger. Further, cyclic AMP (cAMP) is stimulated by NK1R coupled to the Gαs-protein. The neurokinin receptors are expressed on many cell types and tissues. www.MedChemExpress.com 1 Neurokinin Receptor Inhibitors & Modulators Aprepitant Befetupitant (MK-0869; MK-869; L-754030) Cat. No.: HY-10052 (Ro67-5930) Cat. No.: HY-19670 Bioactivity: Aprepitant (MK-0869) is a selective and high-affinity Bioactivity: Befetupitant is a high-affinity, nonpeptide, competitive neurokinin 1 receptor antagonist with a Kd of 86 pM. tachykinin 1 receptor ( NK1R) antagonist. Purity: 99.93% Purity: >98% Clinical Data: Launched Clinical Data: No Development Reported Size: 10mM x 1mL in DMSO, Size: 1 mg, 5 mg, 10 mg, 20 mg 5 mg, 10 mg, 50 mg, 100 mg, 200 mg, 500 mg Fezolinetant Fosaprepitant (ESN-364) Cat. No.: HY-19632 (L-758298) Cat. No.: HY-14407 Bioactivity: Fezolinetant is an antagonist of the neurokinin 3 receptor Bioactivity: Fosaprepitant (L-758298) is a neurokinin-1 receptor antagonist (NK3R), used for the treatment of menopausal hot flushes. -

REED Vulva LA Tak Due 1-15-16 Vulvar Talk LA January 2016.Pptx 1

REED 9/25/18 Vulva LA Tak due 1-15-16 Vulvar Talk LA January 2016.pptx 1-11-2016 UW MEDICINE │ NAMS 2018 DISCLOSURES RECENT ADVANCES IN THE TREATMENT OF VASOMOTOR SYMPTOMS Disclosures: • Royalties from online UpToDate, Scientific American, and ACP Smart KNDy May Be the New Sweet Spot Medicine • Research funding from NIH, Bayer • No COI Trade Names: Every attempt made to present in a nonbiased fashion Definitions: • K = Kispeptin • N = Neurokinin B Istockphoto.com • Dy = dynorphin Susan D Reed, MD, MPH • PRKA = peripherally restricted Professor and Vice Chair kappa agonist Department of Obstetrics and Gynecology Program Director, Women’s Reproductive Health Research Center • NK3R = neurokinin 3 receptor University of Washington, Seattle • NK1R = neurokinin 1 receptor LEARNING OBJECTIVES KNDY NEURONS SECRETE NEUROPEPTIDES After this education, learners should be able to: Kisspeptin: G-protein coupled receptor ligand neuropeptide Describe the rationale for targeting the KNDy (gene kiss1) neuron complex for new therapeutic interventions for menopausal symptoms Neurokinin B: endogenous peptide ligand that belongs to the Understand potential side effects from KNDy family of tachykinin peptides neuron therapeutics (gene TAC) highest affinity NK3R Dynorphin: kappa opiod Describe what is known about drugs in the pipeline that target KNDy KNDy neurons are co-localized with > 95% of ER, PR, AR in arcuate nucleus 1 REED 9/25/18 Vulva LA Tak due 1-15-16 Vulvar Talk LA January 2016.pptx 1-11-2016 WORKING HYPOTHESIS KNDY NEURON PULSE GENERATOR Arcuate