Pragati, Koraput Experiences in System of Ragi Intensification

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Online Donation Re Donation Received on 11-04-2020 On

Chief Minister’s Relief Fund Government Of Odisha https://cmrfodisha.gov.in Online Donation Received on 11-04-2020 The contribution to Chief Minister's Relief Fund entitles the donor to 100% e xemption under section 80 G(2)(iiihf) of Income Tax Act.1961 https://cmrfodisha.gov.in Donor Details Sl. Name and Address of Donor Amount Abinash Sahoo 1 100000 Khurdha Neha Enterprises 2 100000 Khurda Pawan Consumer Care 3 100000 Khurda Alekha Kumar Das 4 51000 Khurdha Sumanta Sathua 5 51000 Puri Chandra Mohan Behera 6 25000 Mayurbhanj Puspita Behera 7 25000 Mayurbhanj Asruta Pritam 8 20000 Bhadrak Forest Range Office Bargarh 9 15790 Bargarh Head Master And Staff 10 15000 Rayagada Turunji Christian Mandali 11 13000 Nabarangpur Basanta Kumar Tripathy 12 11111 Bhubaneswar Soumyakanta Mahalik 13 11111 Angul Ms Krishna Rig Service 14 11000 Kalahandi Prafulla Kumar Gachhayat 15 10001 Khordha Trilochan Mahanta 16 10001 Kendujhar Abhinaba Kumar Rao 17 10000 Sambalpur Bc Kavya 18 10000 Puri Online Donation Received on 11-04-2020 Page 2 https://cmrfodisha.gov.in Bikash Prasad Das 19 10000 Cuttack Debasmita Sahu 20 10000 Jharsuguda Gayatri Jena 21 10000 Cuttack Kumar Sourabh 22 10000 Keonjhar Sanjeeb Kumar Mohanty 23 10000 Khurda S P Kar 24 10000 Sundargarh Sudarshan Send 25 10000 Balasore Veer Surendra Sai Institute Of Medical Science And Research 26 8200 Sambalpur Mohini Hota 27 8096 Sambalpur Santanu Sengupta 28 8000 Sambalpur Prabhu Panda 29 7500 Bhadrak Priyadarshinee Naik 30 5100 Kalahandi Benjamin Kujur 31 5001 Rourkela Mandakini Kar 32 5001 Keonjhar -

Cultural Life of the Tribals of the Koraput Region

Odisha Review ISSN 0970-8669 Cultural Life of the Tribals of the Koraput Region Rabindra Nath Dash If one thinks of cultural history of primitive tribes Literarily the definition of their culture is so broad one must turn towards south Odisha, the hub of that we appreciate and accept every aspect of tribals. So this Koraput region, the domain of their life style which is associated with culture. tribals has become centre of study and research. In 1863 this region was under direct Although the tribal population in Odisha administration of British. The Government of India has around 25%, their contribution in the Act of 1919 declared the entire area of Koraput development process of the state is outstanding. district as Scheduled Area and the major tribes Their tradition and culture is broad and inhabiting the district have been declared as uncommon. And the cultural history of tribals of scheduled tribes. this undivided Koraput has special importance all over India. The tribal population consists of Normally the primitive tribes express the 53.74% in the undivided Koraput (now divided cultural identity through their custom, tradition, into 4 districts Koraput, Rayagada, Nawarangpur, festivals, dress and ornaments. Every tribe has a and Malkangiri) as per 2001 census. The certain place of origin and its spreading. They anthropologist study gives an account that there have their own oral and written language for are 62 types of tribes in Odisha. They all live in interaction of each other. The matrimonial alliance the above districts although their number is so of a tribe is arranged byits own community as small. -

Some Phytotherapeutic Claims by Tribals of Rayagada District, Orissa, India

Ethnobotanical Leaflets 10: 189-197. 2006. Some Phytotherapeutic Claims by Tribals of Rayagada District, Orissa, India Chiranjibi Pattanaik*, Ch. Sudhakar Reddy, N. K. Dhal¹ and Rashmita Das² *Forestry and Ecology Division, National Remote Sensing Agency Hyderabad, Andhra Pradesh, India ¹Natural Products Division, Regional Research Laboratory, CSIR, Bhubaneswar, Orissa, India ²Department of Botany, Berhampur University, Berhampur, Orissa, India *Corresponding author Email: [email protected] Issued 11 August 2006 Abstract The present paper reports with 30 plant species belonging to 23 families, mostly used by the tribal people of Rayagada district, Orissa. The tribal population of the region primarily depends upon these plants for curing various diseases. They are enumerated with binomial, family, habit, local name, parts used and ethnomedicinal uses. Further studies on chemical and pharmacological actions are suggested to validate the claims. Key Words: Phytotherapeutic claim, Ethnomedicine, Tribes, Herbal healer, Orissa. Introduction Use of plant based drugs and chemicals for curing various ailments and personal adornment is as old as human civilization. In India, the sacred Vedas dating back between 3500 B.C and 800 B.C give many references of medicinal plants. One of the remotest works in traditional herbal medicine is “Virikshayurveda”, compiled even before the beginning of Christian era and formed the basis of medicinal studies in ancient India. “Rig Veda”, one of the oldest Indian literatures written around 2000 B.C. mentions the use of Cinnamon (Cinnamomum verum Prel.), Ginger (Zingiber officinale Rose.), Sandalwood (Santalum album L.) etc. not only in religious ceremonies but also in medical preparation (Bentley and Trimen, 1980). Plants and plant-based medicaments are the basis of many of the modern pharmaceuticals we used today for our various ailments (Abraham, 1981; Atal & Kapur, 1982). -

NEW RAILWAYS NEW ODISHA a Progressive Journey Since 2014 Sundargarh Parliamentary Constituency

TIVE Y INDICA MAP IS ONL Shri Narendra Modi Hon'ble Prime Minister NEW RAILWAYS NEW ODISHA A progressive journey since 2014 Sundargarh Parliamentary Constituency SUNDARGARH RAILWAYS’ DEVELOPMENT IN ODISHA (2014-PRESENT) SUNDARGARH PARLIAMENTARY CONSTITUENCY A. ASSEMBLY SEGMENTS : Talsara, Sundargarh, Biramitrapur, Raghunathpali, Rourkela, Rajgangpur, Bonai RAILWAY STATIONS COVERED : Rourkela, Rajgangpur, Bamra, Bondamunda, Garposh, Kanshbahal, Panposh, Kalunga, Tangarmunda, Sonakhan, Sagra, Daghora, Bisra, Nuagaon, Jamga, Himgir, Chandiposi, Kuarmunda, Bimlagarh Junction, Birmitrapur, Barsuan, Dumerta, Lathikata, Dharuadihi, Dhutra, Karampada, Barajamda, Gua, Goilkera, Posoita, Manoharpur, Jaraikela, Bhalulata, Orga B. WORKS COMPLETED IN LAST FIVE YEARS : B.1. New Trains and Stoppages / Extension / Increase in Frequency : Train No. 58660-58659, Rourkela- Hatia-Rourkela passenger started from 09.02.2015. Train No. 78103-78104 Rourkela- Sambalpur-Rourkela DMU started from 07.06.2015. Train No. 12101-12102, Jnaneswari Deluxe Howrah-Lokmanya Tilak Terminus-Howrah provided stoppage at Jharsuguda from 09.05.2017. Train No. 18110-18109, Jammu Tawi MURI Rourkela Express extended from Jammu Tawi to Rourkela and further extended upto Sambalpur w.e.f.12.08.2017. Train No. 18417-18418, Rajya Rani Exp from Rourkela to Bhubaneswar extended upto Gunupur from 21.03.2017. Train No. 18415/18416 Puri-Barbil-Puri Express has been extended upto Rourkela. Train No. 18451/18452 Tapaswini Express has been provided additional stoppage at Kalunga. Train No. 18107/18108 Rourkela-Jagdalpur-Rourkela Express has been provided additional stoppage at Rajgangpur. Train No. 18108/18107 Rourkela - Koraput - Rourkela Express extended upto Jagdalpur. Frequency of 18117/18118 Rourkela-Gunupur-Rourkela Rajyarani Express has been increased to run Daily. B.2. Improvement of Passenger Amenities : Escalators at important stations - 2 Nos at Rourkela at a cost of `1.060 Crore. -

![[-] MI Division, Jeypore](https://docslib.b-cdn.net/cover/2850/mi-division-jeypore-1152850.webp)

[-] MI Division, Jeypore

STATUS OF IRRIGATION SUPPLIED DURING KHARIFF AS ON SEPTEMBER 2015 IN KORAPUT DISTRICT Reason for less/ Length of canal system in Km Ayacut in Ha. excess of ayacut Sl Ayacut Name of District Name of Block Name of MIP Actual length in Actual irrigated/ Reason No. Design Designed irrigated which water Potential for not reaching tail length Ayacut upto 30th supplied Created Sept'2015 end 1 2 3 4 5 6 7 8 9 10 1 Koraput Bandhugam Dondabadi 5.46 3.82 324.00 235.00 235.00 Canal bed silted up. 2 Koraput Bandhugam Kumbhariput 3.00 2.10 59.00 40.00 40.00 Canal bed silted up. 3 Koraput Bandhugam Majhijhola 5.00 3.75 202.00 128.00 128.00 Canal bed silted up. 4 Koraput Bandhugam Yessada 2.40 1.68 81.00 50.00 50.00 Canal bed silted up. 5 Koraput Boipariguda Chikima 15.05 11.28 786.00 680.00 680.00 Canal bed silted up. Canal exisiting up to 6 Koraput Boipariguda Majhiguda 1.00 0.78 55.00 33.00 33.00 0.78 K.M. Field to field 7 Koraput Boipariguda Ramagiri - - 41.00 40.00 40.00 irrigation. Canal exisiting up to 8 Koraput Boipariguda Talamaliguda 2.70 2.14 80.00 40.00 40.00 2.14 K.M. 9 Koraput Boriguma Bairagipadar 2.81 2.04 121.00 92.00 92.00 Canal bed silted up. 10 Koraput Boriguma Benasur 0.68 0.68 46.00 45.00 45.00 Canal bed silted up. 11 Koraput Boriguma Bodigaon 0.28 0.07 69.00 40.00 40.00 Canal bed silted up. -

NEW RAILWAYS NEW ODISHA a Progressive Journey Since 2014 Koraput Parliamentary Constituency

MAP IS ONLY INDICATIVE Shri Narendra Modi Hon'ble Prime Minister NEW RAILWAYS NEW ODISHA A progressive journey since 2014 Koraput Parliamentary Constituency KORAPUT RAILWAYS’ DEVELOPMENT IN ODISHA (2014-PRESENT) KORAPUT PARLIAMENTARY CONSTITUENCY A. ASSEMBLY SEGMENTS : Gunupur, Bissam Cuttack, Rayagada, Lakshmipur, Jeypore, Koraput, Pottangi RAILWAY STATIONS COVERED : Darliput, Padua, Bheja, Machkund Road, Paliba, Suku, Koraput Junction, Dumuriput, Damanjodi, Baiguda, Kakiriguma, Lakshmipur Road, Manabar, Jarati, Jeypore, Kotapad, Jimidipeta, Ladda, Gunupur, Rayagada, Therubali, Singapur Road, Bissam Cuttack, Sansarthali PH., Muniguda, Doikallu, Ambodala, Malligura, Chhatriput, Bhalumaska, Lilliguma, Rauli, Tikri. B. WORKS COMPLETED B.1. New Trains and Stoppages / Extension / Increase in Frequency : ¦ Train No. 58505 Gunupur -Visakhapatnam -Gunupur Passenger has been introduced on 09.02.2015. ¦ Train No. 18111 Tata Nagar- Yesvantpur -Tata Nagar weekly express having stoppage at Rayagada. ¦ Train No. 19453 Gandhidham- Puri-Gandhidham weekly Express introduced w.e.f. 08.10.14 having stoppage at Rayagada. ¦ Train No. 18108/18107 Rourkela - Koraput - Rourkela Express extended upto Jagdalpur. ¦ Train No. 17244 Rayagada - Vijayawada Express has been extended upto Gunupur. ¦ Train No. 18177/18118 Rourkela - Gunupur - Rourkela Rajyarani Express has been increased to run Daily. B.2. Passenger Amenities : ¦ Circulating Area at Sukku, Tikiri, Manabar, Chatriput, Padua, Rayagada, Bheja, Darliput at a cost of ` 0.200 Crores. ¦ WiFi at Rayagada at a cost of ` 1.200 Crore. ¦ Waiting Halls at Lakshmipur Road, Kakrigumma, Dhanapur, Inauguration of Bridge No. 588 by Hon’ble Prime Minster Khadapa, Koraput, Machhkund road, Singapur Road, Padua, Shri Narendra Modi at a function held at Balangir Rayagada at a cost of ` 0.180 Crore. ¦ 2 Urinals at Singapuram Road, 7 Urinals at Rayagada at a cost of ` 0.100 Crore. -

Koraput Traditional Agricultural System, India to Be Designated As Globally Important Agricultural Heritage (GIAHS) Site

Koraput Traditional Agricultural System, India to be designated as Globally Important Agricultural Heritage (GIAHS) site Bhubaneswar, (India)– During the 99th Session of the Indian Science Congress, an important announcement function will take place for the certification of the Traditional Agricultural System of Koraput (Odisha, India) as a Globally Important Agricultural Heritage System (GIAHS) site. The congress, aiming to draw the attention of scientists and stakeholders towards the need to better employ science and technology, will be held from 3 to 7 January 2012 at the Kalinga Institute of Industrial Technology (KIIT), with the participation of over 5000 scientists from all over the world. During his Inaugural Address to the congress, the Prime Minister of India will announce the official recognition of the Koraput System as a GIAHS site for present and future generations, providing outstanding contribution to promoting food security, biodiversity, indigenous knowledge and cultural diversity for sustainable and equitable development. Following on, a special session of the congress will take place, where Dr. Alexander Mueller, Assistant Director-General, Natural Resources Management and Environment Department, will deliver a lecture on “Agricultural Heritage and Food Security in an Era of Climate Change”. Dr. Parviz Koohafkan, Director Land and Water Division and global GIAHS Coordinator, will also participate to the session delivering an address on GIAHS and other important initiatives of the Organization. Odisha is a picturesque state located in the Eastern part of the sub-continent, between the Bay of Bengal and the Eastern Ghats. With its gorgeous rivers, captivating lakes, alluring waterfalls and awe-inspiring temples, it is a land of unique and fascinating beauty. -

Status of Education of Scheduled Tribes in KBK Districts of Orissa

Orissa Review * October - 2009 Status of Education of Scheduled Tribes in KBK Districts of Orissa Atal Bihari Das Introduction: ST constitutes slightly less than 40% of its The role of education in economic population) contributes significantly towards its overall backwardness. development is well recognized by several research studies, economist, Constitution of India, It is well documented that there is a the national policies of education and the five- positive impact of literacy and basic education year plans. The 93rd constitutional amendment on economic productivity of the recipients of made education a fundamental right. The national education. Many empirical research on this topic policy on education, 1986, modified in 1992 from a handful of studies found that the number envisaged free and compulsory education for all of years of schooling (mostly primary schooling) children up to the age of 14 years before the onset is closely related with income or job productivity. of 21st century. To this end a number of policies For example in the agriculture sector, studies have and programmes have been launched. It is widely supported the notion that an additional year of realised that the society with higher percentage primary schooling can directly affect wages and of literates has higher levels of development. farm output. Studies also suggest that an additional Primary education takes a lead in economic year of schooling leads to economic returns that development, as the return to primary education are greater than the cost of education itself is the highest followed by secondary and higher (Haddad et.al, 1990). In view of the contribution education. -

District & Sessions Court Complex, Koraput-Jeypore

District & Sessions Court Complex, Koraput-Jeypore Advocate Reg. No. in Bar Advocate Name Mobile no Email Code Council 69 Ajit Kumar Sahu 797/2012 8599877077 50 Ajit Prasad Mandal 9437069158 103 Amit Kumar Beborta O-1398/2006 9437373516 93 Anand Rath O516/1994 9861566677 [email protected] 61 Anjana Singh 191/2000 9437236591 174 Anup Kumar Patra 241/2006 9437165095 [email protected] 141 Anup Kumar Takri O-1962/1994 9438577158 [email protected] 181 Arati Mishra 374/15 9777336363 64 Arati Mohanty 1793/1995 9437236649 79 Arun Kumar K 399/2002 9437846706 [email protected] 80 Arun Kumar Panda O-1641/1994 9439528847 99 Asha Latha Nandigram 342/1992 8763493877 [email protected] 163 Ashok Kumar Mishra O-943/2003 9437912120 [email protected] 4 Ashok Mishra 0-1180-2005 9437374650 [email protected] 53 Ashok Samantroy 1985 9437720334 173 Aswin Kumar Patnaik O-261/1981 9437375939 [email protected] 39 Balaram Khara 0/459-1985 9439825052 111 Balaram Nayak 8763711811 176 Bansi Dhar Pradhan O-149/1979 7205051691 [email protected] 175 Basant Kumar Patra O-661/1981 9437340030 [email protected] 102 Bhabani Prasad padhy O-2193/1995 9437011535 [email protected] 132 Bhanumati Pujari O-821/2007 9938138281 81 Bijay Kumar Rai Jena Deo O-29/1994 8895511111 172 Binod Chandra Patro New Street Lane Jeyp 9437212750 45 Binod Kumar Patro 0-508/1984 7735039631 13 Binoy Biswas 671/2006 9438362651 [email protected] 90 Bipina Chandra Mohapatro O-559/1984 9437693646 1 Biresh Patnaik 0349/1991 9437102571 [email protected] -

Ganjam District

CHATRAPUR SUB-DIVISION S.I NO POLICE STATION NBWs PENDING FIGURE 1 CHATRAPUR 72 2 GANJAM 10 3 RAMBHA 106 4 CHAMAKHANDI 27 5 KHALLIKOTE 120 6 MARINE 02 TOTAL 337 PURUSOTAMPUR SUB-DIVISION S.I NO POLICE STATION NBWs PENDING FIGURE 1 PURUSOTAMPUR 56 2 KODALA 75 3 POLOSARA 39 4 KABISURYANAGAR 103 TOTAL 273 ASKA SUB-DIVISION S.I NO POLICE STATION NBWs PENDING FIGURE 1 ASKA 606 2 HINJILI 110 3 SHERAGAD A 39 4 PATTAPUR 75 5 DHARAKOTE 109 6 BADAGADA 107 7 SORODA 84 TOTAL 1130 BHANJANAGAR SUB-DIVISION S.I NO POLICE STATION NBWs PENDING FIGURE 1 BHANJANAGAR 245 2 BUGUDA 64 3 GANGAPUR 57 4 J.N.PRASAD 37 5 TARASINGH 66 TOTAL 469 NAME OF SUB-DIVISION TOTAL CHATRAPUR SUB-DIVISION 337 PURUSOTAMPUR SUB-DIVISION 273 ASKA SUB-DIVISION 1130 BHANJANAGAR SUB-DIVISION 469 TOTAL 2209 GANJAM PS Sl No. NBW REF NAME THE FATHERS NAME ADDRESS THE CASE REF WARRANTEE WARRANTEE 1. ADDL SESSION Ramuda Krishna Rao S/O- Roga Rao vill- Malada PS/Dist Ganjam ST-75/13 U/S- 147/148/149/307 JUDGE CTR Ganjam . /323/324/337/294/506/34 IPC . 2. 2nd Addl Dist and Bhalu @ Susanta S/O- Bhakari Gouda vill Maheswar Colony SC- 42/07(A) Session Judge , Gouda PS/Dist Ganjam SC—119/05 Chatrapur 3. ASST SESSION Shyam Sundar Behera S/O- Balaram Behera vill- Kalyamar PS/Dist SC-6/96(3) U/S-147/148/294/307/ JUDGE CHATRAPUR @Babula Ganjam . 506/and 7 crl Amendment Act 4. S.D.J. -

Chapter III Compliance Audit DEPARTMENT of COOPERATION

Chapter III: Compliance Audit Chapter III Compliance Audit Compliance Audit of Departments of Government and their field formation brought out instances of lapses in management of resources and failure in observance of regularity and propriety. These have been discussed in the succeeding paragraphs. DEPARTMENT OF COOPERATION 3.1 Odisha State Agricultural Marketing Board 3.1.1 Introduction Odisha State Agricultural Marketing Board (OSAMB) being an apex statutory body in the State under Cooperation Department was established in 1985 after amendment of Odisha Agriculture Produce Markets (OAPM) Act 1956 in the year 1984 to exercise supervision and control over the working and other affairs of Regulated Market Committees (RMCs). It includes programmes for development of markets and market areas with intention of regulating sale and purchase of agriculture produce in the State. The Board supervises and guides the RMCs in preparation of plan and estimates of construction works undertaken for development of markets and market areas. The objective of this body is to regulate the markets for agriculture produce to ensure payment of fair price to the agriculturists. At present under the control of the Board, 66 RMCs are operating covering 314 Blocks of the State. The above RMCs supervise 483 markets comprising of 54 principal market yards and 429 submarket yards. In addition, 43 krushak bazars were also established. Audit was conducted during April-July 2015 covering the period of five years ending March 2015 in 2017 out of 66 RMCs on the basis of revenue earnings. Audit objectives were to assess whether adequate marketing infrastructure was available and satisfactory mechanism exists to secure fair price for agricultural produce. -

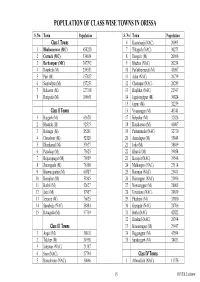

Population of Class Wise Towns in Orissa

POPULATION OF CLASS WISE TOWNS IN ORISSA S. No. Town Population S. No. Town Population Class I Towns 6 Kantabanji (NAC) 20095 1 Bhubaneswar (MC) 658220 7 Titlagarh (NAC) 30273 2 Cuttack (MC) 534654 8 Deogarh (M) 20096 3 Berhampur (MC) 307792 9 Bhuban (NAC) 20234 4 Rourkela (M) 259553 10 Parlakhemundi (M) 43097 5 Puri (M) 157837 11 Aska (NAC) 20739 6 Sambalpur (M) 157253 12 Chatrapur (NAC) 20289 7 Balasore (M) 127358 13 Hinjlikat (NAC) 21347 8 Baripada (M) 100651 14 Jagatsinghpur (M) 30824 15 Jajpur (M) 32239 Class II Towns 16 Vyasanagar (M) 40741 1 Bargarh (M) 63678 17 Belpahar (M) 32826 2 Bhadrak (M) 92515 18 Kendrapara (M) 41407 3 Bolangir (M) 85261 19 Pattamundai (NAC) 32730 4 Choudwar (M) 52528 20 Anandapur (M) 35048 5 Dhenkanal (M) 57677 21 Joda (M) 38689 6 Paradeep (M) 73625 22 Khurda (M) 39054 7 Brajarajnagar (M) 76959 23 Koraput (NAC) 39548 8 Jharsuguda (M) 76100 24 Malkangiri (NAC) 23114 9 Bhawanipatna (M) 60787 25 Karanjia (NAC) 21441 10 Keonjhar (M) 51845 26 Rairangpur (NAC) 21896 11 Barbil (M) 52627 27 Nowrangpur (M) 28005 12 Jatni (M) 57957 28 Umarkote (NAC) 24859 13 Jeypore (M) 76625 29 Phulbani (M) 33890 14 Sunabeda (NAC) 58884 30 Gunupur (NAC) 24706 15 Rayagada (M) 57759 31 Burla (NAC) 42822 32 Hirakud (NAC) 26394 Class III Towns 33 Biramitrapur (M) 29447 1 Angul (M) 38018 34 Rajgangpur (M) 43594 2 Talcher (M) 34998 35 Sundargarh (M) 38421 3 Jaleswar (NAC) 21387 4 Soro (NAC) 27794 Class IV Towns 5 Basudevpur (NAC) 30006 1 Athmallick (NAC) 11376 15 RCUES, Lucknow S.