Adders in Cheshire Andy Harmer

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Catchment News

Cheshire Agricultural Project | Preventing Water Pollution ISSUE 1 Catchment News 1 Cheshire Agricultural Project | Preventing Water Pollution Editorial Taking the CAP off Exploring a brave new In the past 15 years farms have been This is Helm’s preferred proposal given lots of grants but with thousands which would see subsidies cease and world to fund farming of farmers still waiting to receive public money used for public goods this year’s Basic Payment Scheme, directly contracted through public in the post-Brexit and Pillar 1 and 2 payments only bodies. landscape. guaranteed until 2020, one message is coming across loud and clear – we A public good is any good or need to create a new revenue flow if service which when consumed Whether you voted to leave the subsidies dry up. or stay in the European Union by one person, does not reduce last June, we’ve been told in Dieter Helm, Professor of Energy the amount available to others no uncertain terms by Prime Policy at the University of Oxford and it is not possible to supply Minister Theresa May that and Independent Chair of the Natural it to one person without Capital Committee, gave plenty of supplying it to all - clean water, ‘Brexit means Brexit’. food for thought on this subject in his recent Natural Capital Network paper clean air, productive soils, So how will our environment, British Agricultural Policy after BREXIT, carbon storage and biodiversity our soils, our water and our outlining a number of options for a - are public goods that keep biodiversity be managed and way forward: us and our planet healthy and by whom once we divorce from alive. -

Parish Profile

THE PARISH OF ST PETER, HARGRAVE (0510) In the DIOCESE of CHESTER, MALPAS DEANERY PARISH PROFILE 24th February 2021 1 CONTENTS Introduction A popular place to live Church and associated buildings Church worship Huxley Church of England (Controlled) Primary School Church and village activities Finance Forward planning The incumbent This Parish Profile was prepared by members of Hargrave Parochial Church Council and approved by members of the whole PCC. Introduction The Parish of Hargrave, including Huxley, lies about 7 miles south east of Chester, between the roads to Whitchurch (A41) and Nantwich (A51). It is predominantly farmland on the Cheshire plain, overlooked by the Peckforton Hills and also by the castles of Beeston and Peckforton. The river Gowy ambles through the parish eventually feeding the River Mersey and flowing out into the Irish sea between Liverpool and New Brighton. The Parish (0510) forms part of the Malpas Deanery in the Diocese of Chester and is one of 20 Parishes in that Deanery. A Popular, attractive and vibrant place to live. Having been predominantly a farming community for most of its history, the Parish is now attracting residents who mostly travel to work. However several farms still remain, making in total, about 140 dwellings, and a population of less than 500 of all ages. There is a Village Hall in Huxley and, unusually, a new public house called ‘The Inn at Huxley’. Hargrave has the benefit of the Church Hall which also doubles up as a Village Hall. The Parish Church is St. Peter’s at Hargrave. We have the benefit of an excellent butcher’s shop and Deli at ‘The Inn at Huxley.’ There are other shops within a short driving distance at Tattenhall and Tarporley, both of which are lovely Cheshire villages. -

Anfield Bicycle Club Circular

ANFIELD^CIRCULAR JOURNAL OF THE ANFIELD BICYCLE CLUB (formed March 1879) President: Tony Pickles Captain: Martin Cartwright (S: 01244 539979) Hon Secretary: Craig Clewley 92 Victoria Road, SALTNEY, Flintshire, CH4 8SZ (ffi:01244 683022; e-mail: [email protected]) March 2001 no.896 CLUBRUNS (Please support - lunch is 1230hrs) April 7 Llew Coch Ffrwd (Cefn-y-Bedd) 14 Club 7 Huntington 1130hrs White Horse Churton 21 The Buck Bangor-on-Dee 28 The Swan Marbury May 5 Club 7 Huntington 1130hrs White Horse Churton 12 Committee ii30hrs Sportsman's Arms Tattenhall 19 Miner's Arms Minera 26 Yew Tree Spurstow 28 Anfield 100 HQ: Prees Village Hall June 2 The Crown Liandegla 9 The Bull Clotton 16 Trotting Mare Eastwick 20 Midweek Club 7 Huntington (Wednesday) 1930hrs 23 Committee H30hrs Sportsman's Arms Tattenhall 30 ©Miner's AnfieldArms Rhes-y-CaeBicycle Club CLUB SUBSCRIPTIONS 21 and over: £15.00 Junior (under 21): £7.50 Cadet:£3.50 Hon Treasurer: Chris Edwards, Old Orchard, Darmond's Green, West Kirby, WIRRAL CH48 5DT (S: 0151 625 8982) Editor: David Birchall, 53 Beggarmans Lane, KNUTSFORD, WA16 9BA ffi:01565 651593; e-mail: [email protected] * CLOSING DATE FOR NEXT ISSUE - 23 June 2001 * Racing Notes - Mark Livingstone I would like to take this opportunity to wish everyone a Happy New Year and an enjoyable and successful year's cycling and racing (especially the enjoyable bit). Right then, down to business: The first race of the year is almost upon us and it's going to be an interesting one. The Club '14' on March 24th provides everyone with the first of 2 opportunities to put in a good ride in the Club 14 mile handicap competition. -

The Bishop Bennet Way

The Bishop Bennet Way A 34mile/55km route for horse riders following bridleways, byways and minor roads through the countryside of southwest Cheshire For more information about where to ride in Cheshire, visit www.discovercheshire.co.uk Managed by Cheshire & Warrington Tourism Board Managed by Cheshire & Warrington Tourism Board Tarvin A49 Chester A51 A55 A41 Tarporley Start River B5130 The route is named after Dee an eighteenth century traveller Tattenhall Beeston The Bishop Bennet Way who once explored the tracks Farndon A534 Bishop runs from near Beeston Castle to the village that we now ride for pleasure. A41Bennet Way A49 of Wirswall on the Shropshire border. The For information about the life Malpas route is largely on flat ground, with some of Bishop Bennet, visit B5069 Finish Bangor on Dee _ _ gentle hills in its southern half. Some of the www.cheshire.gov.uk/countryside/HorseRiding/bishop bennet way.htm. A525 Whitchurch central sections of the route can be very wet during winter months. The route comprises some 27kms of surfaced roads (mostly without verges) and 12kms of ‘green lanes’ of which some have bridleway status, some restricted byway status, and others byway open to all traffic status. The rest of the route is by field-edge and cross- field paths, the latter being occasionally subject to ploughing. You must expect to share all these routes with walkers and cyclists and, in the case of byways, roads and some restricted byways, with motor traffic too. You should also expect some use of routes by farmers with agricultural vehicles. Using bed and breakfast accommodation for horse and rider, the whole ride can be completed over two consecutive days or you could choose to ride shorter sections individually. -

Fisheries in the North West Incorporating the Annual Summary of Fishery Statistics

1999 annual report on fisheries in the North west incorporating the annual summary of fishery statistics Item Type monograph Publisher Environment Agency North West Download date 06/10/2021 05:18:22 Link to Item http://hdl.handle.net/1834/24894 Fisheries annual report 1999 ENVIRONMENT AGENCY Front Cover Agencies Fisheries Officer Mark Atherton gives the- scout from the 44th Ormskirk scout troop training- to achieve his scout angling badge. 3)3 TIC 1999 ANNUAL REPORT ON FISHERIES IN THE NORTH WEST INCORPORATING THE ANNUAL SUMMARY OF FISHERY STATISTICS Contents Agency fisheries and recreation staff 2 Introduction 3 National overview 4 Regional overview 5 Northern Area 7 Team reports 7 Projects 10 Surveys 16 Central Area 20 Team reports 20 Habitat Improvement Projects 27 Surveys 31 South Area 34 Team reports 34 Projects 35 Surveys 43 APPENDIX Regional Fisheries Advisory Committee Members 1 Consultative Association Contacts 2 Salmon & Sea Trout Catches 3 Rod & Line (From Licence Returns) 1979-1999 4 Net Catches 1979-1999 14 Summary of Fisheries Statistics 1999 22 1 AGENCY FISHERIES AND RECREATION STAFF Fisheries Officers:-John Martin, Mike Dixon, Peter • Richard Fairclough House Evoy, Graeme McKee, John Hadwin Mark Diamond, Principal, Fisheries, Conservation, • Central Area Recreation and Biology, Richard Fairclough House, Knutsford Road, Warrington, WA4 1HG Dafydd Evans, Area Fisheries Ecology and Tel 01925 653999 Recreation Manager, Miran Aprahamian, Senior Fisheries Scientist, PO Box 519, Lutra House, Preston, PR8 8GD Tel Fisheries Science -

(Public Pack)Agenda Document for Southern Planning Committee, 03

Southern Planning Committee Agenda Date: Wednesday, 3rd February, 2016 Time: 10.00 am Venue: Council Chamber, Municipal Buildings, Earle Street, Crewe CW1 2BJ Members of the public are requested to check the Council's website the week the Southern Planning Committee meeting is due to take place as Officers produce updates for some or all of the applications prior to the commencement of the meeting and after the agenda has been published. The agenda is divided into 2 parts. Part 1 is taken in the presence of the public and press. Part 2 items will be considered in the absence of the public and press for the reasons indicated on the agenda and at the foot of each report. PART 1 – MATTERS TO BE CONSIDERED WITH THE PUBLIC AND PRESS PRESENT 1. Apologies for Absence To receive apologies for absence. 2. Declarations of Interest/Pre Determination To provide an opportunity for Members and Officers to declare any disclosable pecuniary and non-pecuniary interests and for Members to declare if they have pre- determined any item on the agenda. 3. Minutes of Previous Meeting (Pages 1 - 8) To approve the minutes of the meeting held on 6 January 2016. Please contact Julie Zientek on 01270 686466 E-Mail: [email protected] with any apologies or requests for further information [email protected] to arrange to speak at the meeting 4. Public Speaking A total period of 5 minutes is allocated for each of the planning applications for the following: Ward Councillors who are not members of the Planning Committee The relevant Town/Parish Council A total period of 3 minutes is allocated for each of the planning applications for the following: Members who are not members of the planning committee and are not the Ward Member Objectors Supporters Applicants 5. -

The Chemical Release and Fire at the Associated Octel Company Limited

Health C Safety Executive Thechemicalm release and fire at the ASSOCIATED OCTEL A REPORT OF THE INVESTIGATION BY THE HEALTH AND SAFETY EXECUTIVE INTO THE CHEMICAL RELEASE AND FIRE AT THE ASSOCIATED OCTEL COMPANY, ELLESMERE PORT ON 1 AND 2 FEBRUARV 4 HSE BOOKS O Crown copyright 1996 Applications for reproduction should be made to HMSO First published 1996 All rights reserved. No part of this publication may be reproduced, stored in a retrieval system or transmitted in any form or by any means (electronic, mechanical photocopying, recording or otherwise) without the prior written permission of the copyright owner. CONTENTS SUMMARY I THE COMPANY AND SITE 3 PLANT AND PROCESS 5 The sodium and chlorination plants 5 The ethyl chloride process 7 Pumps, pipework and valves 9 Chemical hazards 10 THE INCIDENT AND THE EMERGENCY RESPONSE l l The release I I The fire 13 ON-SITE DAMAGE AND INJURIES 14 OFF-SITE IMPACT 14 HSE INVESTIGATION 16 FINDINGS 18 Source of release 18 Maintenance of plant 21 Maintenance prior to the incident 22 Source of ignition 23 Events during the day and in the control room 23 Company risk assessment of the EC plant 25 The on-site and off-site emergency plans 26 How the emergency was handled in relation to the emergency plans 27 Local concerns 30 MANAGEMENT AND SAFETY SYSTEMS 33 Management structure 33 Management of EC plant 35 Health and safety management 35 HSE AND THE ASSOCIATED OCTEL COMPANY LIMITED 37 CONCLUSIONS AND LESSONS TO BE LEARNED 38 Action by the company 43 Action by the Cheshire Fire Authority 45 REFERENCES AND FURTHER READING 46 GLOSSARY OF TERMS 46 APPENDICES APPENDIX 1: MAP OF THE OCTEL SITE AND IMMEDIATE SURROUNDINGS 48 APPENDIX 2: HEALTH AND SAFETY LEGISLATION 49 SUMMARY 1 At about 8.23 pm on 1 February 1994 there was a release of reactor solution from a recirculating pump near the base of a 25 tonne ethyl chloride (EC) reactor vessel at the factory of The Associated Octel Company Ltd, Oil Sites Road, Ellesmere Port, Cheshire. -

Cheshire Minerals Development Framework

Cheshire Minerals Development Framework Core Strategy & Site Specific Policies & Allocations - Issues and Options Strategic Flood Risk Assessment September 2007 Minerals Development Framework Cheshire County Council Minerals Development Framework Strategic Flood Risk Assessment Cheshire County Council – SFRA Minerals Issues and Options 1 documents. September 2007 (v1) Cheshire County Council CHESHIRE MINERALS DEVELOPMENT FRAMEWORK STRATEGIC FLOOD RISK ASSESSMENT Andy Farrow Strategic Planning Manager Waste and Planning Service Cheshire County Council Backford Hall Chester CH1 6PZ For further information please contact: Louise Hilder Daniel Stafford Tel: (01244) 976756 Tel: (01244) 972954 E-mail: E-mail: [email protected] [email protected] This document is available in alternative formats, including large print, Braille, tapes and other languages, on request from Cheshire County Council Media and Promotion Team, County Hall, Chester, CH1 1SF. Phone: 0845 11 333 11 Web site: www.cheshire.gov.uk Email: [email protected] Paper and CDrom copies can be obtained: By post: Pat Fricker Team Leader, Information Management Waste and Planning Service Cheshire County Council Backford Hall Backford Chester CH1 6PZ Tel: 01244 973766 Fax 01244 603033 Email: [email protected] Web site: www.cheshire.gov.uk/Planning/ Cheshire County Council – SFRA Minerals Issues and Options 1 documents. September 2007 (v1) Contents 1.0 Introduction 1 Planning Policy Statement 25 1 Approach to Producing SFRA 2 2.0 Summary of Flood Risk in Cheshire -

Baseline Report Series: 2. the Permo-Triassic Sandstones of West Cheshire and the Wirral

Baseline Report Series: 2. The Permo-Triassic Sandstones of west Cheshire and the Wirral Groundwater Systems and Water Quality Commissioned Report CR/02/109N National Groundwater & Contaminated Land Centre Technical Report NC/99/74/2 The Natural Quality of Groundwater in England and Wales A joint programme of research by the British Geological Survey and the Environment Agency Contents FOREWORD iv BACKGROUND TO THE BASELINE PROJECT v 1. EXECUTIVE SUMMARY 1 2. PERSPECTIVE 2 3. BACKGROUND TO UNDERSTANDING BASELINE QUALITY 6 3.1 Geology 6 3.2 Hydrogeology 11 3.3 Aquifer mineralogy 15 3.4 Rainfall chemistry 15 4. DATA AND INTERPRETATION 18 4.1 Groundwater sampling programme 18 4.2 Historical data 18 4.3 Interpretation of pumped groundwater samples 20 4.4 Data handling 21 5. HYDROCHEMICAL CHARACTERISTICS 22 5.1 Introduction 22 5.2 Water types and physicochemical characteristics 24 5.3 Major elements 26 5.4 Minor and trace elements 28 5.5 Pollution indicators 31 6. GEOCHEMICAL CONTROLS AND REGIONAL CHARACTERISTICS 32 6.1 Introduction 32 6.2 Chemical evolution along flowlines 32 6.3 Temporal variations 39 6.4 Age of the groundwater 42 6.5 Regional variations 43 7. BASELINE CHEMISTRY OF THE AQUIFER 48 8. SUMMARY AND CONCLUSIONS 49 REFERENCES 50 i List of Figures Figure 2.1 Topographic map of the West Cheshire and Wirral Area 4 Figure 2.2 View of Mid Cheshire Ridge along the east of the study area, taken near Peckforton Castle 3 Figure 2.3 Land use map of the study area. 5 Figure 2.4 View from Helsby Hill towards the Mersey Estuary, illustrating the industrial and agricultural land use in the area. -

Flood Warning

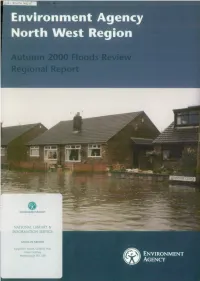

Environment Agency North West Region NATIONAL LIBRARY & INFORMATION SERVICE ANGLIAN REGION Kingfisher House, Goldhay Way, Orton Goldhay, Peterborough PE2 SZR Jeff Lawrenson Regional Flood Defence Manager Richard Fairclough House Knutsford Road Warrington WA4 1HG Tel: 01925 653 999 Fax: 01925 415 961 ISBN 185705 572 1 ©Environment Agency l All rights reserved. No part of this document may be reproduced, stored in a retrieval system, or transmitted, in any form or by any means, electronic, mechanical, photocopying, recording or otherwise, without the prior permission of the Environment Agency. Cover: Flooding in Common Lane Brook area, Leigh (30th October 2000) HO-4/01-150-A Printed on recycled paper Floods Report October/November 2000 Environment Agency North West ENVIRONMENT AGENCY NORTH WEST REGION OCTOBER/NOVEMBER 2000 FLOODS REPORT CONTENTS List of Tables..........................................................................................................................5 List of Figures.........................................................................................................................7 List of Abbreviations............................................................................................................9 Executive Summary............................................................................................................11 1. Introduction.............................................................................................................17 1.1 Introduction................................................................................................ -

Local Environment Agency Plan

local environment agency plan WEAVER/DANE CONSULTATION REPORT OCTOBER 1997 nutsford Biddul, E n v ir o n m e n t A g e n c y NATIONAL LIBRARY & INFORMATION SERVICE ANGLIAN REGION Kingfisher House, Goldhay Way, Orton Goldhay, Peterborough PE2 5ZR En v ir o n m e n t Ag ency Weaver/Dane Key Details • Total Area 1423 km2 • Population c.500,000 • Administrative Details District Councils Vale Royal Chester Newcastle-under-Lyme Congleton High Peak Warrington North Shropshire Crewe & Nantwich Staffordshire Moorlands Halton Macclesfield • Water Resources Largest Abstraction (at Brunner Mond, Northwich) 165,478 m3/day Average Annual Rainfall 716 mm Number of River Level only Measuring Stations 3 Number of River Level & Flow Measuring Stations 7 Number of Raingauges 25 • Flood Protection Length of Designated "Main River" Watercourses 619.4 km (Maintained by the Environment Agency) • Water Quality Length of classified river and canal 623.8 km • Fisheries Length of trout fishery 93 km Length of coarse fishery 187 km • Conservation Number of Sites of Special Scientific Importance (SSSI) 81 Number of Sites of Biological Importance (SBI) 412 • Heritage Sites Number of Scheduled Ancient Monuments (SAMs) 30 Number of Conservation Areas 12 NB These figures are for designated sites located near to "main river" & therefore, do not include all sites within the area boundary. • Integrated Pollution Control/Radioactive Substances I PC sites 21 Authorised Processes 49 RAS Authorisations 7 Registrations 33 • Waste Regulation Number of licensed sites 63 Number of registered exempt sites 114 Number of registered carriers of waste 375 ENVIRONMENT AGENCY Weaver/Dane LEAP The Environment Agency Kingfisher House, Goldhay Way, Orton Goldhay, i ^ ENVIRONMENT Peterborough PE2 5ZR. -

Fl946558 Tn-36895

The Ancestry of JANE THORNTON OF SPARTANBURG South Carolina DAIE MICROFILM 2-/3-73 ITEM ON ROLL H Wife of Arthur Hutchens of Albemarle Parish, Virginia CAMERA NO, CATALOGUE NO. and Ancestress of Clarence Edmund Crowley By ARIEL L. CROWLEY, Ph. D. Idaho City, Idaho 83631 June lb, 1969 ftn ^LUOICAi 891, I'M 7 i INTRODUCTION In proper theory, I suppose, there should be, and perhaps one day vie may see it, but one vast and flawless genealogy, in which the intricacies of human relationships and descent will be perfectly defined (Rev. 20:12). For nresent practical convenience, in spite of the manifest flaws and inadequacies of search and records which beset all genealogists, a second little volume in aid of those who search for the maternal ancestry and ties of Clarence Edmund Crowley (1881-1967) distinguished lawyer and father of this compiler, seems requisite. The point of departure is Harriet Ante Ida Hutchens who married Squire Green Crowley 18 October 1875. She was a daughter of William Birch Hutchens whose ancestry is detailed in the previous volume, FRANCIS HUTCHENS, Immigrant 165U. The real problem in the prior volume was solution of the mystery of the parentage cf Arthur Hutchens,of Spartanburg, grandfather of William Birch Hutchens. Even so, in this volume a solution is offered as to Jane Thornton of Spartanburg, wife of Arthur Hutchens. It is obvious that many doors are now open to those who wish to look more deeply into these ancestral ways. It is hoped that this volume may shortly be followed by others until a comprehensive view may be obtained.