The-Party-1943.Pdf

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Método De Interpretación De La Historia Argentina Interpretación La Presente Reedición Reproduce La Publicación De Pluma De 1975

Bases para una interpretación científica de la historia argentina Folletos mimeografiados desde 1965 Primera edición de imprenta en sección publicaciones Facultad de Arquitectura y Urbanismo, Universidad Nac de Córdoba, 1972 Método de Primera edición ampliada y corregida por el autor, con la colaboración de Hugo Kasevich, por Editorial Pluma, Buenos Aires, 1975 bajo el título: Método de interpretación de la historia argentina interpretación La presente reedición reproduce la publicación de Pluma de 1975 de la historia Cuatro tesis sobre la colonización española y portuguesa Ediciones mimeografiadas desde 1948 Revista Estrategia, Nº 1, 1957 argentina Fue republicado junto a otros trabajos en: Feudalismo y capitalismo en la colonización de América, Ediciones Avanzada, julio 1972 Para comprender la historia, George Novack, Pluma, Buenos Aires, 1975 Ediciones El Socialista, noviembre 2012 Maquetación: María Isabel Lorca Nahuel Moreno Queda hecho en el depósito que establece la Ley 11.723 www.izquierdasocialista.org.ar www.uit-ci.org www.nahuelmoreno.org ©Copyright by Ediciones El Socialista Buenos Aires, 2012 Ediciones PRESENTACIÓN por el castrismo, quien morirá trágicamente en julio de 1964 junto Presentación con casi toda la primera célula de un abortado proyecto foquista.1 En ese período, el rearme teórico era decisivo: el partido de Moreno estaba en tratos de unidad con el Frente Revolucionario Indoamericano Popular (FRIP), un grupo que actuaba en Tucumán y Santiago del Estero, liderado por los hermanos Amílcar, Mario Nahuel Moreno, el político y Francisco “el Negro” Santucho, un apasionado de los estudios de historia colonial. Dotar al partido de una visión estructurada que “hizo historia” de la historia nacional permitía debatir temas que concluían en cuestiones programáticas y teóricas de primera importancia, como las consignas de transición hacia el socialismo, el papel de Por Ricardo de Titto* la clase obrera y del campesinado y la pequeñoburguesía urbana en esa lucha y, por consiguiente, el propio carácter del partido. -

Joseph Hansen Papers

http://oac.cdlib.org/findaid/ark:/13030/tf78700585 No online items Register of the Joseph Hansen papers Finding aid prepared by Joseph Hansen Hoover Institution Archives 434 Galvez Mall Stanford University Stanford, CA, 94305-6003 (650) 723-3563 [email protected] © 1998, 2006, 2012 Register of the Joseph Hansen 92035 1 papers Title: Joseph Hansen papers Date (inclusive): 1887-1980 Collection Number: 92035 Contributing Institution: Hoover Institution Archives Language of Material: English Physical Description: 109 manuscript boxes, 1 oversize box, 3 envelopes, 1 audio cassette(46.2 linear feet) Abstract: Speeches and writings, correspondence, notes, minutes, reports, internal bulletins, resolutions, theses, printed matter, sound recording, and photographs relating to Leon Trotsky, activities of the Socialist Workers Party in the United States, and activities of the Fourth International in Latin America, Western Europe and elsewhere. Physical Location: Hoover Institution Archives Creator: Hansen, Joseph, Access The collection is open for research; materials must be requested at least two business days in advance of intended use. Publication Rights For copyright status, please contact the Hoover Institution Archives. Preferred Citation [Identification of item], Joseph Hansen papers, [Box no., Folder no. or title], Hoover Institution Archives. Acquisition Information Acquired by the Hoover Institution Archives in 1992. Accruals Materials may have been added to the collection since this finding aid was prepared. To determine if this has occurred, find the collection in Stanford University's online catalog at http://searchworks.stanford.edu . Materials have been added to the collection if the number of boxes listed in the online catalog is larger than the number of boxes listed in this finding aid. -

Perú Y La Estrategia Armada En Los Años Sesenta: La Reactualización De Un Debate

Contenciosa , Año IV, nro.6, primer semestre 2016 - ISSN 2347-0011 PERÚ Y LA ESTRATEGIA ARMADA EN LOS AÑOS SESENTA: LA REACTUALIZACIÓN DE UN DEBATE MARTÍN MANGIANTINI (Instituto Ravignani – CONICET / UBA) Facultad de Filosofía y Letras / Universidad de Buenos Aires Becario del Consejo Nacional de Investigaciones Científicas y Técnicas / Instituto Ravignani (25 de Mayo 221, 2° piso, CABA) [email protected] Resumen A principios de los años sesenta, la organización trotskista argentina Palabra Obrera decidió el envío de tres militantes al Perú con el objetivo de construcción e inserción política en un contexto de importante convulsión social, principalmente a partir de la toma de tierra y la sindicalización campesina en la región del Cuzco. La puesta en práctica de acciones armadas por parte de este grupo generó un proceso de discusión y debate que, recientemente, se trajo a colación a raíz de una serie de nuevos insumos documentales. Es objetivo de este artículo analizar este hecho a la luz de estas flamantes herramientas de discusión. Palabras Claves Lucha armada - Trotskismo - Movimiento campesino - Guevarismo Abstract At the beginning of the sixties, the Trotskyist Argentine organization Palabra Obrera (Working Word) decided to send three militants to Peru with the aim of construction and of political insertion in a context of important social convulsion, principally from the capture of land and the rural unionization in the region of the Cuzco. The implementation of armed actions by this group generated a process of discussion and debate that, recently, was brought to collation immediately after a series of new documentary inputs. It is the aim of this article to analyze this fact in the light of these brand new discussion tools. -

The Democratic Socialist Party & the Fourth International

The Democratic Socialist Party & the Fourth International Jim Percy & Doug Lorimer 2 The Democratic Socialist Party & the Fourth International Contents Introduction ..................................................................................3 Trotskyism & the Socialist Workers Party by Jim Percy.................4 Isolation & the circle spirit....................................................................................6 Making a fetish of ‘program’................................................................................ 9 Two errors........................................................................................................... 14 Internationalism & an international................................................................... 18 Clearing away obstacles...................................................................................... 20 Lenin’s method.................................................................................................... 23 Learning from the Cubans................................................................................. 25 Organising the party........................................................................................... 26 The 12th World Congress of the Fourth international & the future of the Socialist Workers Party’s international relations by Doug Lorimer......................................30 Debate on world political situation.................................................................... 32 Debate over ‘permanent revolution’................................................................. -

No. 245, December 7, 1979

WORKERS ,,16(;0I1R' 25¢ -~.... ~-, ... No. 245 .. •J:l.... '~y X·523 7 December 1979 Desnite Khomeini'sDeath Wish for Iran 010 It ;;an't go on much longer without a ready to die for the "imam" and the head-on crash between the world's most Americans who have made a fashion of dangerous imperialist power and the "Nuke the Ayatollah" T-shirts. world's most powerful medievalist The U.S. media counts off the days religious fanatic. Not for much longer for a frustrated. angry and humiliated can Khomeini threaten to hold trials population. while a group of congress and execute the hostages at the U.S. men have organized a campaign to "set embassy in Teheran while he calls forth the date" for military retaliation. ABC Islamic wrath against the "American TV runs a near-nightly news special Satan." and taunts Carter for having entitled. "America Held Hostage." and "no guts." It cannot go on indefinitely. Tillli' magazine's tlag-and-eagle cover thiS gathering of U.S. warships and demands to know: "Has America Lost aircraft off the coast of the Arabian Its Clout')" peninsula and these storm clouds of war No. it can't go on much longer. sentiment on the streets of America and Despite the efforts to "play it cool." Iran. Carter's war threats are real. and the In the bizarre events of the last month conscLJuences terriblc~tor the masses there IS a tearful S) mmetr) in the lunatiC of Iran and the international proletanat. pronouncements of the 79-year-old nut For the ultimate target in the \\'1'1" with state powcr in Qum who says that room of U.S. -

Wfjrkers ,,IN'ij,IR'25¢

WfJRKERS ,,IN'IJ,IR' 25¢ No. 316 .~~~~. X-S23 29 October 1982 Protesters·Rout Klan- Boston COliS Riot UPI .iiiJII'iI BOSTON, October 16-Hooded and j 1 I • white-sheeted Ku Klux Klansmen were • surrounded by an angry, jeering crowd of 1.500. pelted with eggs. and. scared II ;:,ut of their w~ts, were tlln off the sheets of Boston today. Not even a full-scale riot by scores of motorcycle and mounted police defending the KKKers could disperse the protesters. who came determined to stop the fascists' provoca tion. It was the first solid anti-racist stand after years of unrelieved racist terror for black people in Boston. October 16 was a stunning blow against the cross-burners and lynchers that has been heard across the whole country. Under Reagan reaction, the KKK figures it has a license to spew out its race-hate poison everywhere. A Klan endorsed president in the White House, Democrats and Republicans united in an anti-Soviet war drive have made it open season on unions and minority rights at home. And Boston is where rampaging mobs ofwhite racists took to the streets against busing. An ideal place for a Klan march, figured "imperial wizard" Bill Wilkinson. But the all WV Photo purpose hate mongers of the KKK not (Above) Boston cops protect Klan. (Below) Spartaclst contingent on October 16. only target blacks, Jews, communists, labor: Catholics are also high on their TV cringing. The cops, meanwhile, protesters in Cambridge Street. Motor the Plaza, directed this time at the hit list. So when Wilkinson said he'd began beating on anyone around, cycle cops roared into the crowd in City police. -

UC Santa Barbara Dissertation Template

UNIVERSITY OF CALIFORNIA Santa Barbara Defining the Monster: The Social Science and Rhetoric of Neo-Marxist Theories of Imperialism in the United States and Latin America, 1945-1973 A dissertation submitted in partial satisfaction of the requirements for the degree Doctor of Philosophy in History by Christopher Cody Stephens Committee in charge: Professor Nelson Lichtenstein, Chair Professor Alice O’Connor Professor Salim Yaqub June 2018 The dissertation of Christopher Cody Stephens is approved. ____________________________________________ Salim Yaqub ____________________________________________ Alice O’Connor ____________________________________________ Nelson Lichtenstein, Committee Chair April 2017 ACKNOWLEDGEMENTS I had the benefit of working with many knowledgeable and generous faculty members at UCSB. As my advisor and the chair of my dissertation committee, Nelson Lichtenstein has ushered the project through every stage of its development, from conceptualization to defense. I pitched the idea of writing a seminar paper on Andre Gunder Frank in his office roughly four years ago, and since then he has enthusiastically supported my efforts, encouraged me to stay focused on the end goal, and provided detailed feedback on multiple drafts. That is not to say that I have always incorporated all his comments/criticisms, but when I have failed to do so it is mostly out of lack of time, resources, or self-discipline. I will continue to draw from a store of Nelson’s comments as a blueprint as I revise the manuscript for eventual publication as a monograph. Alice O’Connor, Mary Furner, and Salim Yaqub also read and commented on the manuscript, and more broadly influenced my intellectual trajectory. Salim helped me present my work at numerous conferences, which in turn helped me think through how the project fit in the frame of Cold War historiography. -

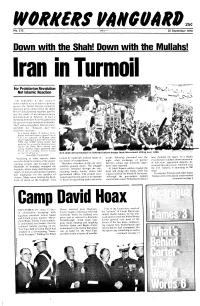

Down with the Shah! Down with the Mullahs! • Ran in I

WORKERS VIIN(JIJIIR' 25¢ t..ln .. ;';;'i.~,~.• ~2J 1'0 .... 215 '. '~6b""!" .. 22 September 1978 Down with the Shah! Down with the Mullahs! • ran In I For Proletarian Revolution Not Islamic Reaction On Septemher S, this summer's uninterrupted waH: of massi\C protests against the hrutal Iranian monarch~ reached a grisly climax \vhen the shah's Royal Guard poured machine gun fire into the ranks of an anti-government demonstration in Teheran. At least a thousand protesters were slaughtered in the greatest single massacre in decades. Ihe l.ondon Guardian's Teheran corre spondent, Lif Thurgood, gave this e\cwitness account: In a hrutal display of military force, troops and small tanb opened fire at Y·.20 am. vesterdav in Madan Jaleh [.Ialeh Slju,lre] at a spot where hetween 5.()()O and IO.OOD young people had gathered lor a peaeeful demonstration a~ainst the Shah. Men. women. and Y;lung children, many splattered with hloc,d. ran screaming. 'Thev're killing Setbourld,.'S iP;;:B';:;~},"Star us. the\'re killiilg us'." Anti-shah demonstration in Teheran before troops fired into crowd, killing over 1,000. Guardian 9 Septemher later doubled the figure. In a Majlis According to other reports, tanks treated by makeshift medical teams in trucks. Shooting continued into the ("parliament") debate shown on nation moved in from the corners of the square, the homes of sympathizers. night. when exchanges of gunfire al television, opposition deputies de crushing corpses and wounded alike. Marchers elsewhere in the city were between troops and unknown oppo similarly gunned down. -

Nahuel Moreno to Be Trotskyist Today Written: 1985 Spanish First Edition: Cuadernos De Correo Internacional (International Courier Booklets), 1988

Nahuel Moreno To be Trotskyist today Written: 1985 Spanish First Edition: Cuadernos de Correo Internacional (International Courier Booklets), 1988. English First Edition: Ediciones El Socialista, 2013 English Translation: Daniel Iglesias, 2013 www.nahuelmoreno.org Let's start with understanding what it means to be truly Marxist. We cannot make a cult, as it has been done for Mao or Stalin. Being Trotskyist today does not mean agreeing with everything that Trotsky wrote or said, but to know how to critique or exceed him, same as with Marx, Engels or Lenin, because Marxism intends to be scientific and science teaches that there are no absolute truths. This is the first thing, to be Trotskyist is to be critical, including of Trotskyism itself. On the positive side, to be Trotskyist is to respond to three clear analysis and programmatic positions. The first is that while capitalism exists in the world or a country, there is no real solution for absolutely any problem — starting with education, art, and getting to the more general problems of hunger, increased poverty, etc. Coupled with this, although not exactly the same, the approach that a merciless struggle is needed against capitalism until their defeat, to impose a new economic and social order in the world that cannot be other than socialism. Second problem, in those places where the bourgeoisie has been expropriated (I speak of the USSR and of all countries that call themselves socialist), there is no solution if workers' democracy does not prevail. The great evil, the syphilis of world labour movement is bureaucracy, the totalitarian methods that exist in these countries and labour organizations, unions, parties who claim to be of the working class, and have been corrupted by the bureaucracy. -

Nahuel Moreno Letter to Gonzalez Moscoso (Bolivia)

CEHuS Centro de Estudios Humanos y Sociales Nahuel Moreno Letter to Gonzalez Moscoso (Bolivia) Nahuel Moreno Letter to Gonzalez Moscoso (Bolivia) September 1965 Taken from Revista de America No 6-7, July–October 1971 English translation: Daniel Iglesias Editor notes: Daniel Iglesias Cover and interior design: Daniel Iglesias www.nahuelmoreno.org www.uit-ci.org www.izquierdasocialista.org.ar Copyright by CEHuS , Centro de Estudios Humanos y Sociales Buenos Aires, 2021 [email protected] CEHuS Centro de Estudios Humanos y Sociales Contents Foreword ...................................................................................... 1 Letter to Gonzalez Moscoso (Bolivia) ........................................... 2 The need for a newspaper and revolutionary political course ................ 2 It is urgent to agree on the nature of the stage and the government .... 4 The current situation ............................................................................... 4 From which organisations will we help the miners? ............................... 5 The problem of the United Front ............................................................. 5 The United Front in relation to the problem of power ............................ 6 The big task: To prepare for the armed struggle ..................................... 6 The use of legality ................................................................................... 7 Conclusions .............................................................................................. 7 Editorial -

Argentina: a Triumphant Democratic Revolution

Nahuel Moreno Argentina: A Triumphant Democratic Revolution Ediciones Nahuel Moreno Argentina: A Triumphant Democratic Revolution First Spanish Edition Spanish Edition: Internal document of PST, 1984 First Spanish Book Edition: Ediciones Crux, Buenos Aires, 1992 First English Internet Edition:: Ediciones El Socialista, Buenos Aires, 2015 Cover and interior design: Daniel Iglesias Cover Picture: Movilisation on 30 April 1982 www.nahuelmoreno.org www.uit-ci.org www.izquierdasocialista.org.ar Contents Foreword .......................................................................................................................................1 Part I: A Triumphant Democratic Revolution ........................................................................................2 Part II The stages of the Argentine revolution ....................................................................................16 Part III Our party and its political line ...................................................................................................29 Ediciones ARGENTINA: A TRIUMPHANT DEMOCRATIC REVOLUTION Foreword This work was published for the first time to the public in 1992 by Ediciones Crux in their Unpublished Collection as an appendix to Party Cadres’ School: Argentina 1984, already published by www.nahuelmoreno.org. We believe it is appropriate to publish it for the first time in English, although in many parts it is similar to Revolutions of the XX Century and 1982: The Revolution Begins, because in the first chapter there are some -

Nahuel Moreno Cehus

CEHuS Centro de Estudios Humanos y Sociales Nahuel Moreno The break with Pabloism Nahuel Moreno The break with Pabloism 1953 (Archive material) English Translation: Daniel Iglesias Cover and interior design: Daniel Iglesias www.nahuelmoreno.org www.uit-ci.org www.izquierdasocialista.org.ar Copyright by CEHuS Centro de Estudios Humanos y Sociales Buenos Aires, 2020 [email protected] CEHuS Centro de Estudios Humanos y Sociales Contents Foreword ......................................................................................................... 1 The break with Pabloism A. Letter to the International Secretariat ......................................................... 3 A false quote which is a method: Disloyalty in small and large things ....................................... 5 From the world war as a very probable trend without a fixed term of the present time… ......... 7 … War as inevitable at a fixed-term of two to four years ......................................................... 10 From a workers’ bureaucracy (particularly Stalinist) that in an exceptional case can unite or lead the revolution… ................................................................................................................. 13 … To a bureaucracy that will inevitably lead the revolution to the taking of power .................. 14 … To a long-term world strategy of taking over the non-Trotskyist revolutionary parties or the revolutionary centrist tendencies .............................................................................................