University News 633 CLARK STREET EVANSTON, ILL

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Cmsa's Class of 2017 Students Celebrate 308 Acceptances

FOR IMMEDIATE RELEASE Contact: Irene Bermudez, 773 761 8960, ext. 306 [email protected] CMSA’S CLASS OF 2017 STUDENTS CELEBRATE 308 ACCEPTANCES TO COLLEGES INCLUDING IVY LEAGUE SCHOOLS AND $13,338,680 IN MERIT SCHOLARSHIPS! Chicago, IL – (April 19, 2017) – Chicago Math and Science Academy (CMSA) proudly announces that students in the Class of 2017 have received 308 acceptances from colleges, including Ivy League Schools, and have earned a total of over $13 million in merit scholarships! Here is a list of the schools where our students are accepted: Brown University, Cornell University ,University of Chicago, Northwestern University, Loyola University, Marquette University , Illinois Institute of Technology, Roosevelt University, DePaul University, University of Illinois Chicago, University of Illinois Urbana Champaign, Augustan College, Beloit College, Benediction University, Boston University, Bradley University, Butler University, Capital University, Carthage College, Case Western Reserve University, Central State University, Columbia College, Concordia University, Dominican University, Drake University, Eastern Kentucky University, Elmhurst College, Full Sail University, Georgia State University, Goshen College, Grinnell College, Hamilton College, Harry S. Truman College, Hampton University, Hofstra University, Illinois College, Illinois State University, Illinois Wesleyan University, Indiana University, Indiana University Purdue University, Iowa Wesleyan University, Ithaca College, Jackson State University, Kalamazoo College, -

AIR Guard Albion College American Honors at Ivy Tech Community

AIR Guard Indiana Army National Guard Rose-Hulman Albion College Indiana State University Saint Louis University American Honors at Ivy Tech Community College Indiana Tech Saint Mary's College American National University Indiana University Kokomo Salem International University Ancilla College Indiana University School of Social Work Samford University Anderson University Indiana University-Purdue University Fort Wayne Savannah State University Augustana College Indiana Wesleyan University School of Advertising Art Aviation Technology Center ISM College Planning Simmons College of Kentucky Baldwin Wallace University IU Bloomington Smith College Ball State University IU Kelley School of Business Indianapolis Southern Illinois University Carbondale Boyce College (Southern Baptist Theological IUPUI Taylor University Seminary) IUPUI Army ROTC The Art Institutes Bradley University IUPUI, Herron School of Art and Design The University of Alabama Brescia University Kendall College of Art & Design The University of Toledo Butler University Kettering University Tougaloo College Central Michigan University Lawrence University Transylvania University Cleveland State University Lourdes University Trine University Columbia College in Missouri Loyola University Chicago United States Air Force Concordia University Chicago Marian University University of Cincinnati Denison University Miami University University of Indianapolis DePauw University Michigan Technological University University of Kentucky Dominican University Midwest Technical Institute University -

Admissions Brochure

College of Engineering & Computer Science Syracuse University ecs.syr.edu Personal attention. Approachable faculty. The accessibility of a small college set within the en less opportunities of a comprehensive university. An en uring commitment to the community. Team spirit. A rive to o more. Transforming together. Welcome to Syracuse University’s College of Engineering an Computer Science, where our spirit unites us in striving for nothing less than a higher quality of life for all—in a safer, healthier, more sustainable world. Together, we are e icate to preparing our stu ents to excel at the highest levels in in ustry, in aca emia—an in life. Message from the Dean Inquisitive. Creative. Entrepreneurial. These are fun amental attributes of Syracuse engineers an computer scientists. Unlike ever before, engineers an computer scientists are a ressing the most important global an social issues impacting our future—an Syracuse University is playing an integral role in shaping this future. The College of Engineering an Computer Science is a vibrant community of stu ents, faculty, staff, an alumni. Our egree programs evelop critical thinking skills, as well as han s-on learning. Our experiential programs provi e opportunities for research, professional experience, stu y abroa , an entrepreneurship. Dean Teresa Abi-Na er Dahlberg, Ph.D. Through cutting e ge research, curricular innovations, an multi- isciplinary collaborations, we are a ressing challenges such as protecting our cyber-systems, regenerating human tissues, provi ing clean water supplies, minimizing consumption of fossil fuels, an A LEADIN MODEL securing ata within wireless systems. Our stu ents stan out as in ivi uals an consistently prove they can be successful as part of a team. -

Chapter 3: the Rise of the Antinuclear Power Movement: 1957 to 1989

Chapter 3 THE RISE OF THE ANTINUCLEAR POWER MOVEMENT 1957 TO 1989 In this chapter I trace the development and circulation of antinuclear struggles of the last 40 years. What we will see is a pattern of new sectors of the class (e.g., women, native Americans, and Labor) joining the movement over the course of that long cycle of struggles. Those new sectors would remain autonomous, which would clearly place the movement within the autonomist Marxist model. Furthermore, it is precisely the widening of the class composition that has made the antinuclear movement the most successful social movement of the 1970s and 1980s. Although that widening has been impressive, as we will see in chapter 5, it did not go far enough, leaving out certain sectors of the class. Since its beginnings in the 1950s, opposition to the civilian nuclear power program has gone through three distinct phases of one cycle of struggles.(1) Phase 1 —1957 to 1967— was a period marked by sporadic opposition to specific nuclear plants. Phase 2 —1968 to 1975— was a period marked by a concern for the environmental impact of nuclear power plants, which led to a critique of all aspects of nuclear power. Moreover, the legal and the political systems were widely used to achieve demands. And Phase 3 —1977 to the present— has been a period marked by the use of direct action and civil disobedience by protesters whose goals have been to shut down all nuclear power plants. 3.1 The First Phase of the Struggles: 1957 to 1967 Opposition to nuclear energy first emerged shortly after the atomic bomb was built. -

Jieda Li Education Work Experience Technial Skills

JIEDA LI https://www.linkedin.com/in/jieda/ | 612-805-5828 | [email protected] EDUCATION Northwestern University, Evanston, IL Expected: Dec 2020 Master of Science in Analytics (MSiA) Relevant Courses: Predictive Analytics, Machine Learning, Data Mining, Text Analytics, Big Data Southern Methodist University (SMU), Dallas, TX May 2010 Master of Science in Electrical Engineering (GPA: 3.85/4.0) University of Electronic Science and Technology of China (UESTC), Chengdu, China Jun 2007 Bachelor of Science in Electrical Engineering (GPA: 3.79/4.0, graduated with highest honor) WORK EXPERIENCE Apple, Cupertino, CA May 2017 – May 2019 Hardware Engineer • Responsible for key circuit block validation for several generations of Apple SOC chip. • Authored Test automation software to perform automated test for Apple chip (Python, Git). • Processed raw test data into publishable results/visualizations (Pandas, Matplotlib, Seaborn). • Developed a deep learning model for integrated circuit performance prediction (Keras). • Presented a machine learning tutorial to fellow engineers (15-people group). • Contributed to team-effort in re-architecting test software and constructing data pipeline. • Received top performance reviews for work quality and effective team collaboration. Oracle, San Diego, CA. Oct 2010 – Jan 2017 Senior Hardware Engineer / Hardware Engineer / Engineer Intern • Responsible for high-speed electrical link system architecture design and validation. • Built system simulator for performance simulation and architecture optimization (MATLAB). • Built test automation software that measures performance of high-speed IO (LabView). • Granted with 1 U.S. patent and published 3 peer-reviewed technical papers. Southern Methodist University, Dallas, TX Aug 2007 – May 2010 Graduate Research Assistant • Designed, fabricated and characterized an innovative integrated photonic device. -

Chicago: North Park Garage Overview North Park Garage

Chicago: North Park Garage Overview North Park Garage Bus routes operating out of the North Park Garage run primarily throughout the Loop/CBD and Near Northside areas, into the city’s Northeast Side as well as Evanston and Skokie. Buses from this garage provide access to multiple rail lines in the CTA system. 2 North Park Garage North Park bus routes are some busiest in the CTA system. North Park buses travel through some of Chicago’s most upscale neighborhoods. ● 280+ total buses ● 22 routes Available Media Interior Cards Fullbacks Brand Buses Fullwraps Kings Ultra Super Kings Queens Window Clings Tails Headlights Headliners Presentation Template June 2017 Confidential. Do not share North Park Garage Commuter Profile Gender Age Female 60.0% 18-24 12.5% Male 40.0% 25-44 49.2% 45-64 28.3% Employment Status 65+ 9.8% Residence Status Full-Time 47.0% White Collar 50.1% Own 28.9% 0 25 50 Management, Business Financial 13.3% Rent 67.8% HHI Professional 23.7% Neither 3.4% Service 14.0% <$25k 23.6% Sales, Office 13.2% Race/Ethnicity $25-$34 11.3% White 65.1% Education Level Attained $35-$49 24.1% African American 22.4% High School 24.8% Hispanic 24.1% $50-$74 14.9% Some College (1-3 years) 21.2% Asian 5.8% >$75k 26.1% College Graduate or more 43.3% Other 6.8% 0 15 30 Source: Scarborough Chicago Routes # Route Name # Route Name 11 Lincoln 135 Clarendon/LaSalle Express 22 Clark 136 Sheridan/LaSalle Express 36 Broadway 146 Inner Drive/Michigan Express 49 Western 147 Outer Drive Express 49B North Western 148 Clarendon/Michigan Express X49 Western Express 151 Sheridan 50 Damen 152 Addison 56 Milwaukee 155 Devon 82 Kimball-Homan 201 Central/Ridge 92 Foster 205 Chicago/Golf 93 California/Dodge 206 Evanston Circulator 96 Lunt Presentation Template June 2017 Confidential. -

Lake Michigan

ASHLAND AVE. ISABELLA ST. AVE. ASBURY MILBURN ST. Miller Park Wieboldt House Trienens (one block north) Performance Drysdale Field President’s Residence LAKE Center 2601 Orrington Avenue Northwestern University MICHIGAN Welsh-Ryan Arena/ Long Field Evanston, Illinois McGaw Memorial Hall Career Advancement Patten Gymnasium/ LINCOLN ST. Anderson LINCOLN ST. Gleacher Golf CAMPUS DR. Ryan RD. SHERIDAN Center Field Hall Inset is one Beach block north and 3/4 mile Norris Aquatics west Student CENTRAL ST. Student Center Residences Residences COLFAX ST. COLFAX ST. BRYANT AVE. Student Residences Ryan Fieldhouse and Tennis North Wilson Field Courts Campus Parking Garage RIDGE AVE. Walter ORRINGTON AVE. ORRINGTON Crown Sports Pavilion/ GRANT ST. Athletics DARTMOUTH PL. Student The Garage Combe Tennis Center SHERMAN AVE. SHERMAN Center Residences N. CAMPUS DR. International Christie Student and Tennis Scholar Services Center Lakeside Martin Frances Field Stadium CTA Station TECH DR. Searle Building NOYES ST. NOYES ST. NOYES ST. TECH DR. CTA TO CHICAGO TO CTA Mudd Thomas Technological Building Athletic SIMPSON ST. Institute Complex Inset is Cook Hall 1-1/2 blocks Ryan Family south Auditorium Hutcheson LEONARD PL. and Lutheran Hogan Biological Kellogg Field HAVEN ST. 1/3 mile Center Sciences Building Global Hub ASBURY AVE. ASBURY west LEON PL. TECH DR. SHERIDAN R SHERIDAN GAFFIELD PL. 2020 Ridge Catalysis RIDGE AVE. Shakespeare Center Ryan Garden Ford Motor Hall Student Pancoe-NSUHS Company Dearborn Allen Residences Life Sciences Engineering Observatory Silverman Hall Center D Design Center Pavilion FOSTER . GARRETT PL. Garrett-Evangelical Annenberg Hall Sheil Theological Seminary Catholic SIMPSON ST. SIMPSON ST. Center SIMPSON ST. NORTHWESTERN PL. -

From Wilderness to the Toxic Environment: Health in American Environmental Politics, 1945-Present

From Wilderness to the Toxic Environment: Health in American Environmental Politics, 1945-Present The Harvard community has made this article openly available. Please share how this access benefits you. Your story matters Citation Thomson, Jennifer Christine. 2013. From Wilderness to the Toxic Environment: Health in American Environmental Politics, 1945- Present. Doctoral dissertation, Harvard University. Citable link http://nrs.harvard.edu/urn-3:HUL.InstRepos:11125030 Terms of Use This article was downloaded from Harvard University’s DASH repository, and is made available under the terms and conditions applicable to Other Posted Material, as set forth at http:// nrs.harvard.edu/urn-3:HUL.InstRepos:dash.current.terms-of- use#LAA From Wilderness to the Toxic Environment: Health in American Environmental Politics, 1945-Present A dissertation presented by Jennifer Christine Thomson to The Department of the History of Science In partial fulfillment of the requirements for the degree of Doctor of Philosophy in the subject of History of Science Harvard University Cambridge, Massachusetts May 2013 @ 2013 Jennifer Christine Thomson All rights reserved. Dissertation Advisor: Charles Rosenberg Jennifer Christine Thomson From Wilderness to the Toxic Environment: Health in American Environmental Politics, 1945-Present Abstract This dissertation joins the history of science and medicine with environmental history to explore the language of health in environmental politics. Today, in government policy briefs and mission statements of environmental non-profits, newspaper editorials and activist journals, claims about the health of the planet and its human and non-human inhabitants abound. Yet despite this rhetorical ubiquity, modern environmental politics are ideologically and organizationally fractured along the themes of whose health is at stake and how that health should be protected. -

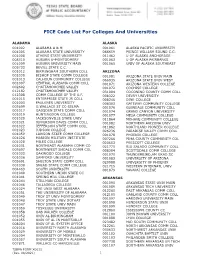

FICE Code List for Colleges and Universities (X0011)

FICE Code List For Colleges And Universities ALABAMA ALASKA 001002 ALABAMA A & M 001061 ALASKA PACIFIC UNIVERSITY 001005 ALABAMA STATE UNIVERSITY 066659 PRINCE WILLIAM SOUND C.C. 001008 ATHENS STATE UNIVERSITY 011462 U OF ALASKA ANCHORAGE 008310 AUBURN U-MONTGOMERY 001063 U OF ALASKA FAIRBANKS 001009 AUBURN UNIVERSITY MAIN 001065 UNIV OF ALASKA SOUTHEAST 005733 BEVILL STATE C.C. 001012 BIRMINGHAM SOUTHERN COLL ARIZONA 001030 BISHOP STATE COMM COLLEGE 001081 ARIZONA STATE UNIV MAIN 001013 CALHOUN COMMUNITY COLLEGE 066935 ARIZONA STATE UNIV WEST 001007 CENTRAL ALABAMA COMM COLL 001071 ARIZONA WESTERN COLLEGE 002602 CHATTAHOOCHEE VALLEY 001072 COCHISE COLLEGE 012182 CHATTAHOOCHEE VALLEY 031004 COCONINO COUNTY COMM COLL 012308 COMM COLLEGE OF THE A.F. 008322 DEVRY UNIVERSITY 001015 ENTERPRISE STATE JR COLL 008246 DINE COLLEGE 001003 FAULKNER UNIVERSITY 008303 GATEWAY COMMUNITY COLLEGE 005699 G.WALLACE ST CC-SELMA 001076 GLENDALE COMMUNITY COLL 001017 GADSDEN STATE COMM COLL 001074 GRAND CANYON UNIVERSITY 001019 HUNTINGDON COLLEGE 001077 MESA COMMUNITY COLLEGE 001020 JACKSONVILLE STATE UNIV 011864 MOHAVE COMMUNITY COLLEGE 001021 JEFFERSON DAVIS COMM COLL 001082 NORTHERN ARIZONA UNIV 001022 JEFFERSON STATE COMM COLL 011862 NORTHLAND PIONEER COLLEGE 001023 JUDSON COLLEGE 026236 PARADISE VALLEY COMM COLL 001059 LAWSON STATE COMM COLLEGE 001078 PHOENIX COLLEGE 001026 MARION MILITARY INSTITUTE 007266 PIMA COUNTY COMMUNITY COL 001028 MILES COLLEGE 020653 PRESCOTT COLLEGE 001031 NORTHEAST ALABAMA COMM CO 021775 RIO SALADO COMMUNITY COLL 005697 NORTHWEST -

Air Force ROTC at Illinois Institute of Tech Albion College Allegheny

Air Force ROTC at Illinois Institute of Tech Colgate University Albion College College of DuPage Allegheny College College of St. Benedict and St. John's University Alverno College Colorado College American Academy of Art Colorado State University Andrews University Columbia College-Chicago Aquinas College Columbia College-Columbia Arizona State University Concordia University-Chicago Auburn University Concordia University-WI Augustana College Cornell College Aurora University Cornell University Ball State University Creighton University Baylor University Denison University Belmont University DePaul University Blackburn College DePauw University Boston College Dickinson College Bowling Green State University Dominican University Bradley University Drake University Bucknell University Drexel University Butler University Drury University Calvin College East West University Canisius College Eastern Illinois University Carleton College Eastern Michigan University Carroll University Elmhurst College Carthage College Elon University Case Western Reserve University Emmanuel College Central College Emory University Chicago State University Eureka College Clarke University Ferris State University Florida Atlantic University Lakeland University Florida Institute of Technology Lawrence Technological University Franklin College Lawrence University Furman University Lehigh University Georgia Institute of Technology Lewis University Governors State University Lincoln Christian University Grand Valley State University Lincoln College Hamilton College -

William Kunstler: Disturbing the Universe a Film by Emily Kunstler and Sarah Kunstler

William Kunstler: Disturbing the Universe A film by Emily Kunstler and Sarah Kunstler POV www.pbs.org/pov DISCUSSION GUIDE William Kunstler: Disturbing the Universe POV Letter frOm the fiLmmakers NEw YorK , 2010 Dear Colleague, William kunstler: Disturbing the Universe grew out of conver - sations that Emily and I began having about our father and his impact on our lives. It was 2005, 10 years after his death, and Hurricane Katrina had just shredded the veneer that covered racism in America. when we were growing up, our parents imbued us with a strong sense of personal responsibility. we wanted to fight injustice; we just didn’t know what path to take. I think both Emily and I were afraid of trying to live up to our father’s accomplishments. It was in a small, dusty Texas town that we found our path. In 1999, an unlawful drug sting imprisoned more than 20 percent of Tulia’s African American population. The injustice of the incar - cerations shocked us, and the fury and eloquence of family members left behind moved us beyond sympathy to action. while our father lived in front of news cameras, we found our place behind the lens. our film, Tulia, Texas: Scenes from the Filmmakers Emily Kunstler and Sarah Kunstler. Photo courtesy of Maddy Miller Drug War helped exonerate 46 people. one day when we were driving around Tulia, hunting leads and interviews, Emily turned to me. “I think I could be happy doing this for the rest of my life,” she said, giving voice to something we had both been thinking. -

Report on Closed Institutions and Teach-Out Locations in Illinois

Item #I-2 December 4, 2018 Report on Closed Institutions and Teach-out Locations in Illinois Submitted for: Information Summary: This agenda item presents a report of institutions that have closed or commenced teach-out from 2016 to 2018. Action Requested: None. 331 332 Item #I-2 December 4, 2018 STATE OF ILLINOIS BOARD OF HIGHER EDUCATION Report on Closed Institutions and Teach-out Locations in Illinois The Illinois Board of Higher Education (IBHE) administers the Private College Act and the Academic Degree Act, two Illinois statutes regulating the operation and degree-granting activity of private colleges and universities in the state of Illinois. IBHE Academic Affairs staff maintain accurate records of institutional authorities and review institutions to ensure compliance with relevant administrative code. Institutions must show evidence of financial health, accreditation/regulatory compliance, and integrity of program implementation. There are a variety of reasons why an institution may close including compliance issues, accreditation/regulatory actions, financial problems, and corporate/institutional restructuring. Through each scenario, IBHE Academic Affairs staff work with institutions to coordinate teach-out plans and manage the disposition of records, all in a manner to protect Illinois students and ensure compliance with administrative code. IBHE Academic Affairs staff maintain an institutional closure website to provide information to current and former students, as well as other interested parties, regarding student transcripts,