Changes to the Drivers of Fire Weather with a Warming Climate – a Case Study of Southeast Tasmania

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

6. Annual Review and Significant Events

6. Annual Review and Significant Events January-April: wet in the tropics and WA, very hot in central to eastern Australia For northern Australia, the tropical wet season (October 2005 – April 2006) was the fifth wettest on record, with an average of 674 mm falling over the period. The monsoon trough was somewhat late in arriving over the Top End (mid-January as opposed to the average of late December), but once it had become established, widespread heavy rain featured for the next four months, except over the NT and Queensland in February. One particularly noteworthy event occurred towards the end of January when an intense low (central pressure near 990 hPa) on the monsoon trough, drifted slowly westward across the central NT generating large quantities of rain. A two-day deluge of 482 mm fell at Supplejack in the Tanami Desert (NT), resulting in major flooding over the Victoria River catchment. A large part of the central NT had its wettest January on record. Widespread areas of above average rain in WA were mainly due to the passages of several decaying tropical cyclones, and to a lesser extent southward incursions of tropical moisture interacting with mid-latitude systems. Severe tropical cyclone Clare crossed the Pilbara coast on 9t h January and then moved on a southerly track across the western fringes of WA as a rain depression. Significant flooding occurred around Lake Grace where 226 mm of rain fell in a 24-hour period from 12 t h to 13 t h January. Tropical cyclone Emma crossed the Pilbara coast on 28 th February and moved on a southerly track; very heavy rain fell in the headwaters of the Murchison River on 1s t March causing this river’s highest flood on record. -

Edition 2 from Forest to Fjaeldmark the Vegetation Communities Highland Treeless Vegetation

Edition 2 From Forest to Fjaeldmark The Vegetation Communities Highland treeless vegetation Richea scoparia Edition 2 From Forest to Fjaeldmark 1 Highland treeless vegetation Community (Code) Page Alpine coniferous heathland (HCH) 4 Cushion moorland (HCM) 6 Eastern alpine heathland (HHE) 8 Eastern alpine sedgeland (HSE) 10 Eastern alpine vegetation (undifferentiated) (HUE) 12 Western alpine heathland (HHW) 13 Western alpine sedgeland/herbland (HSW) 15 General description Rainforest and related scrub, Dry eucalypt forest and woodland, Scrub, heathland and coastal complexes. Highland treeless vegetation communities occur Likewise, some non-forest communities with wide within the alpine zone where the growth of trees is environmental amplitudes, such as wetlands, may be impeded by climatic factors. The altitude above found in alpine areas. which trees cannot survive varies between approximately 700 m in the south-west to over The boundaries between alpine vegetation communities are usually well defined, but 1 400 m in the north-east highlands; its exact location depends on a number of factors. In many communities may occur in a tight mosaic. In these parts of Tasmania the boundary is not well defined. situations, mapping community boundaries at Sometimes tree lines are inverted due to exposure 1:25 000 may not be feasible. This is particularly the or frost hollows. problem in the eastern highlands; the class Eastern alpine vegetation (undifferentiated) (HUE) is used in There are seven specific highland heathland, those areas where remote sensing does not provide sedgeland and moorland mapping communities, sufficient resolution. including one undifferentiated class. Other highland treeless vegetation such as grasslands, herbfields, A minor revision in 2017 added information on the grassy sedgelands and wetlands are described in occurrence of peatland pool complexes, and other sections. -

Derwent Catchment Review

Derwent Catchment Review PART 1 Introduction and Background Prepared for Derwent Catchment Review Steering Committee June, 2011 By Ruth Eriksen, Lois Koehnken, Alistair Brooks and Daniel Ray Table of Contents 1 Introduction ..........................................................................................................................................1 1.1 Project Scope and Need....................................................................................................1 2 Physical setting......................................................................................................................................1 2.1 Catchment description......................................................................................................2 2.2 Geology and Geomorphology ...........................................................................................5 2.3 Rainfall and climate...........................................................................................................9 2.3.1 Current climate ............................................................................................................9 2.3.2 Future climate............................................................................................................10 2.4 Vegetation patterns ........................................................................................................12 2.5 River hydrology ...............................................................................................................12 2.5.1 -

Liawenee Flume Project

Liawenee Flume Project of consumables by boat over 12,000 miles from Barnsley in the United Kingdom to Hobart. On arrival in Hobart, we were met by Hydro Tasmania repre- sentative Norm Cribbin, whose help, local knowledge and sup- port were to prove invaluable, plus he carried the snakebite kits! Also there were representatives of JDP Coatings, a potential new installer for Australia. We hired a small truck and a large station Liawenee flume is situated high in the mountains north of Ho- wagon, loaded up and set off up the mountain. bart, capital city of Tasmania, an island 180 miles south of Aus- At site we unloaded the preparation equipment and set about tralia. Hobart is Australia’s second oldest and southernmost city, removing the moss, growths and unsound areas from the sur- next stop Antarctica. face with a high-pressure jet washer and in more difficult areas Fernco Environmental Ltd. is an U.K. company that markets a with a pneumatic scabbler. For the next stage we sprayed the unique range of products targeted at the preservation, conserva- whole area to be coated with a dilute bleach as a mild biocide tion, harvesting and recycling of water assets. We presented Fernco Ultracoat, an epoxy coating system de- The challenges were a remote site, no facilities veloped by Warren Environmental, to Tasmania Hydro, highlight- whatsoever, in a national park, an area of conservation, ing its special qualities as a no VOCs, high build in one coat, conditions varied from freezing to +20 degrees Celsius. structurally reinforcing and rapidly applied epoxy coating system with over 15 years of successful in ground history. -

Listing Statement

THREATENED SPECIES LISTING STATEMENT ORCHID L iawenee greenhood Pterostylis pratensis D. L. Jones 1998 Status Tasmanian Threatened Species Protection Act 1995 ……………………………….……..………..………………..vulnerable Commonwealth Environment Protection and Biodiversity Conservation Act 1999 ……………………..….….…...............Vulnerable Hans & Annie Wapstra Description December. In flower, the plants are 7 to 15 cm tall, Pterostylis pratensis belongs to a group of orchids with many closely sheathing stem leaves. They commonly known as greenhoods because the dorsal have 2 to 12 densely crowded white flowers with sepal and petals are united to form a predominantly dark green stripes. The hood apex curves down green, hood-like structure that dominates the abruptly and terminates with a short tip. The two flower. When triggered by touch, the labellum flips lateral sepals hang down and are fused to form a inwards towards the column, trapping any insect pouch below the labellum though the tips may inside the flower, thereby aiding pollination as the remain free. The labellum, which also hangs down, insect struggles to escape. Greenhoods are is whitish green, oblong with a shallowly notched deciduous terrestrials that have fleshy tubers, which tip and has an appendage that points out with a dark are replaced annually. At some stage in their life green, knob-like apex with a short, broad, blunt cycle all greenhoods produce a rosette of leaves. beak about 0.5 mm long. In all, the flowers are 7 to 8.5 mm long and 4.5 mm wide. The rosette of Pterostylis pratensis encircles the base of the flower stem. The 4 to 8 rosette leaves Its darker green and white flowers and larger leaves are dark green, crowded, and oval to circular can distinguish Pterostylis pratensis, which grows shaped with the broadest part in the middle, 25 to in montane and subalpine regions on the Central 35 mm long and 14 to 22 mm wide. -

Australian Orchidaceae: Genera and Species (12/1/2004)

AUSTRALIAN ORCHID NAME INDEX (21/1/2008) by Mark A. Clements Centre for Plant Biodiversity Research/Australian National Herbarium GPO Box 1600 Canberra ACT 2601 Australia Corresponding author: [email protected] INTRODUCTION The Australian Orchid Name Index (AONI) provides the currently accepted scientific names, together with their synonyms, of all Australian orchids including those in external territories. The appropriate scientific name for each orchid taxon is based on data published in the scientific or historical literature, and/or from study of the relevant type specimens or illustrations and study of taxa as herbarium specimens, in the field or in the living state. Structure of the index: Genera and species are listed alphabetically. Accepted names for taxa are in bold, followed by the author(s), place and date of publication, details of the type(s), including where it is held and assessment of its status. The institution(s) where type specimen(s) are housed are recorded using the international codes for Herbaria (Appendix 1) as listed in Holmgren et al’s Index Herbariorum (1981) continuously updated, see [http://sciweb.nybg.org/science2/IndexHerbariorum.asp]. Citation of authors follows Brummit & Powell (1992) Authors of Plant Names; for book abbreviations, the standard is Taxonomic Literature, 2nd edn. (Stafleu & Cowan 1976-88; supplements, 1992-2000); and periodicals are abbreviated according to B-P- H/S (Bridson, 1992) [http://www.ipni.org/index.html]. Synonyms are provided with relevant information on place of publication and details of the type(s). They are indented and listed in chronological order under the accepted taxon name. Synonyms are also cross-referenced under genus. -

LAKE SECONDARY ROAD MIENA to HAULAGE HILL ROAD SEALING Submission to the Parliamentary Standing Committee on Public Works Version: 1 Date: August 2017

LAKE SECONDARY ROAD MIENA TO HAULAGE HILL ROAD SEALING Submission to the Parliamentary Standing Committee on Public Works Version: 1 Date: August 2017 State Roads Division Department of State Growth Document Development History Build Status Version Date Author Reason Sections Amendments in this Release Section Title Section Amendment Summary Number Distribution Copy No Version Issue Date Issued To ROAD SEALING Submission to the Parliamentary Standing Committee on Public Works Version: 1 Date: August 2017 Table of Contents 1 INTRODUCTION ........................................................................................................................................ 1 1.1 BACKGROUND ............................................................................................................................................. 1 1.2 PROJECT OBJECTIVES .................................................................................................................................... 1 1.3 PROJECT LOCATION ...................................................................................................................................... 2 1.4 STRATEGIC CONTEXT OF THE PROJECT .............................................................................................................. 3 2 PROJECT DETAILS ..................................................................................................................................... 4 2.1 PROPOSED WORKS ..................................................................................................................................... -

Hobart Derwent Bridge

LSC DH NF LSC LSC TW BO NN DONAGHYS HILL LOOKOUT NELSON FALLS NATURE TRAIL LAKE ST CLAIR THE WALL BOTHWELL Pause for a break on the road and take the Stretch your legs and make the short climb to Australia’s deepest lake was carved out by glaciers. It’s the end This large-scale artwork is lifetime’s work for self- Established in the 1820s by settler-graziers from Scotland easy walk to a lookout point over buttongrass see a rainforest cascade. point of the famous Overland Track, one of the world’s best multi- taught sculptor Greg Duncan, who is carving the stories (with some notable Welsh and Irish connections) this town plains to see a bend of the upper Franklin day walks. Spend an hour or so in the Lake St Clair Park Centre, of the high country in 100 panels of Huon pine, each has more than 50 heritage-listed buildings. It is the site River – on the skyline is the white quartzite where you’ll learn about the region’s amazing geology, fascinating three metres high and a metre wide. of Australia’s oldest golf course, on the historic property summit of Frenchmans Cap. Lake Burbury flora & fauna and rich human heritage. ‘Ratho’. ‘Nant’ is another of the town’s heritage properties TO THE WEST: explore wilderness, Lake St Clair and the source of acclaimed single-malt whisky. TO THE EAST: follow the Derwent Queenstown QU Nelson Falls discover wild history LH NF Nature Trail LSC down to a city by the sea THE WALL Bronte Park THE LYELL HIGHWAY WR Derwent Bridge TW Linking the West Coast with Hobart, the highway you’re on ST crosses the high country of the Central Plateau and runs Strahan through the Tasmanian Wilderness World Heritage Area. -

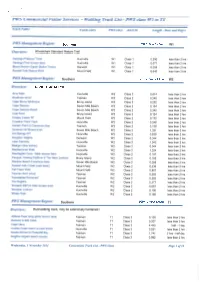

Walking Track List - PWS Class Wl to T4

PWS Commercial Visitor Services - Walking Track List - PWS class Wl to T4 Track Name FieldCentre PWS class AS2156 Length - Kms and Days PWS Management Region: Southern PWS Track Class: VV1 Overview: Wheelchair Standard Nature Trail Hastings Platypus Track Huonville W1 Class 1 0.290 less than 2 hrs Hastings Pool access track Huonville W1 Class 1 0.077 less than 2 hrs Mount Nelson Signal Station Tracks Derwent W1 Class 1 0.059 less than 2 hrs Russell Falls Nature Walk Mount Field W1 Class 1 0.649 less than 2 hrs PWS Management Region: Southern PWS Track Class: W2 Overview: Standard Nature Trail Arve Falls Huonville W2 Class 2 0.614 less than 2 hrs Blowhole circuit Tasman W2 Class 2 0.248 less than 2 hrs Cape Bruny lighthouse Bruny Island W2 Class 2 0.252 less than 2 hrs Cape Deslacs Seven Mile Beach W2 Class 2 0.154 less than 2 hrs Cape Deslacs Beach Seven Mile Beach W2 Class 2 0.345 less than 2 hrs Coal Point Bruny Island W2 Class 2 0.124 less than 2 hrs Creepy Crawly NT Mount Field W2 Class 2 0.175 less than 2 hrs Crowther Point Track Huonville W2 Class 2 0.248 less than 2 hrs Garden Point to Carnarvon Bay Tasman W2 Class 2 3.138 less than 2 hrs Gordons Hill fitness track Seven Mile Beach W2 Class 2 1.331 less than 2 hrs Hot Springs NT Huonville W2 Class 2 0.839 less than 2 hrs Kingston Heights Derwent W2 Class 2 0.344 less than 2 hrs Lake Osbome Huonville W2 Class 2 1.042 less than 2 hrs Maingon Bay lookout Tasman W2 Class 2 0.044 less than 2 hrs Needwonnee Walk Huonville W2 Class 2 1.324 less than 2 hrs Newdegate Cave - Main access -

Conserving Cultural Values in Australian National Parks and Reserves, with Particular Reference to the Tasmanian Wilderness World Heritage Area

Conserving Cultural Values in Australian National Parks and Reserves, with Particular Reference to the Tasmanian Wilderness World Heritage Area by Simon Cubit BEd (Hons) Submitted in fulfilment of the requirements for the degree of Doctor of Philosophy School of Geography and Environmental Studies University of Tasmania Australia Declaration This thesis contains no material which has been accepted for the award of any other degree or diploma in any tertiary institution and to the best of my knowledge and belief, the thesis contains no material previously published or written by another person, except where due reference is made in the text. Simon Cubit This thesis may be made available for loan. Copying of any part of this thesis is prohibited for two years from the date this statement was signed; after that time limited copying is permitted is accordance with the CopyrightAct 1968. .�? """ © Simon Cubit Abstract Beginning in the 1970s and extending into the 1990s community groups, academics and cultural heritage managers in Australia noted with concern the expression of a management philosophy which encouraged the devaluing and removal of European cultural heritage in national parks and protected areas. In the 1990s when the phenomenon became the subject of academic and professional analysis, it was attributed to a longstanding separation in Western notions of culture and nature which underpinned a conflict between the ascendant concept of wilderness and the artefacts of human use and association. As the century drew to a close, these expressions of concern began to fade in line with the emergence of new international valuations of the natural world which rejected wilderness in favour of the conservation of biodiversity. -

On Developing a Historical Fire Weather Data-Set for Australia

Australian Meteorological and Oceanographic Journal 60 (2010) 1-14 On developing a historical fire weather data-set for Australia Christopher Lucas Centre for Australian Weather and Climate Research, a partnership between the Bureau of Meteorology and CSIRO, Melbourne, Australia (Manuscript received May 2009, revised October 2009) The creation of a national historical fire weather data-set, extending from 1973 to 2008, is described. For this purpose, fire weather is described using the McArthur Forest Fire Danger Index (FFDI). A detailed deconstruction of the FFDI and its sensitivities is presented. To create the data-set, meteorological measurements of air temperature, relative humidity, wind speed and rainfall are required. A total of 77 stations are used. At many of these stations, the input data are non-ho- mogeneous. A particularly concerning issue for the fire weather data-set here is the inhomogeneity of the wind measurements, largely a consequence of different measurement instrumentation and methodologies implemented over the decades. Monte Carlo techniques are used to investigate the sensitivity of the distribution of the FFDI to changes in the distribution of the wind. The mean wind speed is shown to have the largest effect. A method for estimating the magnitude of the errors introduced is presented. Introduction The study of past weather and climate is a crucial step in even when human values are not directly affected there can understanding the world around us. Weather and climate be an impact on biodiversity and the ecosystem as a whole. vary across the entire spectrum of temporal and spatial Bushfires are largely a function of the weather and climate. -

Journey Into Central Highlands Heritage — and the Power of the Big Idea the Human Spirit That Was Almost a Disaster

Journey into Central Highlands heritage — and the power of The big idea the human spirit that was almost a disaster The Great Lake Power Scheme was the brainchild of Central Highlands sheep farmer, Harold Bisdee, and his brother-in-law, Alexander McAulay, a university physics professor. Together with metallurgist, James Gillies, they battled to establish it as a private enterprise, until impending war in Europe cut off new capital. The Tasmanian Government took over the scheme in 1914, forming the Hydro-Electric Department — Australia’s first public, statewide energy generating enterprise. “ …Tasmania was practically destitute The visionary scheme came of manufacturing close to disaster many times, industries. Now with formidable snowstorms, new industries are For more information: industrial unrest, impossibly starting every few Highlands Power Trail heavy construction gear, months.” 1300 360 441 (Mon–Fri, business hours) specialist equipment delayed Northern Advocate [email protected] by World War I, and budgets newspaper, New Zealand, www.highlandspowertrail.com.au that ran out. 17 April 1923 What you see as you explore was part of the sacrifice and endeavor that changed and Heritage Office Archive Photo: Tasmanian the fate of an island — from the abandoned tennis court at Waddamana Village to giant handmade spanners at the power station and a canal that looks more architectural than industrial. The scheme and other hydropower developments that followed it brought change on a scale unparalleled. It created what became a statewide The development of the Highlands Power Trail has been supported by Hydro electricity grid, a new economy and a fresh direction. Tasmania, Central Highlands Council, and the Australian Government.