Jump Blues, Club Blues, and Roy Brown Rob Bowman

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Internet Killed the B-Boy Star: a Study of B-Boying Through the Lens Of

Internet Killed the B-boy Star: A Study of B-boying Through the Lens of Contemporary Media Dehui Kong Senior Seminar in Dance Fall 2010 Thesis director: Professor L. Garafola © Dehui Kong 1 B-Boy Infinitives To suck until our lips turned blue the last drops of cool juice from a crumpled cup sopped with spit the first Italian Ice of summer To chase popsicle stick skiffs along the curb skimming stormwater from Woodbridge Ave to Old Post Road To be To B-boy To be boys who snuck into a garden to pluck a baseball from mud and shit To hop that old man's fence before he bust through his front door with a lame-bull limp charge and a fist the size of half a spade To be To B-boy To lace shell-toe Adidas To say Word to Kurtis Blow To laugh the afternoons someone's mama was so black when she stepped out the car B-boy… that’s what it is, that’s why when the public the oil light went on changed it to ‘break-dancing’ they were just giving a To count hairs sprouting professional name to it, but b-boy was the original name for it and whoever wants to keep it real would around our cocks To touch 1 ourselves To pick the half-smoked keep calling it b-boy. True Blues from my father's ash tray and cough the gray grit - JoJo, from Rock Steady Crew into my hands To run my tongue along the lips of a girl with crooked teeth To be To B-boy To be boys for the ten days an 8-foot gash of cardboard lasts after we dragged that cardboard seven blocks then slapped it on the cracked blacktop To spin on our hands and backs To bruise elbows wrists and hips To Bronx-Twist Jersey version beside the mid-day traffic To swipe To pop To lock freeze and drop dimes on the hot pavement – even if the girls stopped watching and the street lamps lit buzzed all night we danced like that and no one called us home - Patrick Rosal 1 The Freshest Kids , prod. -

Mark III Owners Manual

MESA-BOOGIE MARK III OPERATING INSTRUCTIONS MESA ENGINEERING CONGRATULATIONS! You've just become the proud owner of the world's finest guitar amplifier. When people come up to compliment you on your tone, you can smile knowingly ... and hopefully you'll tell them a little about us! This amplifier has been designed, refined and constructed to deliver maximum musical performance of any style, in any situation. And in order to live up to that tall promise, the controls must be very powerful and sophisticated. But don't worry! Just by following our sample settings, you'll be getting great sounds immediately. And as you gain more familiarity with the Boogie's controls, it will provide you with much greater depth and more lasting satisfaction from your music. THREE MODES For approximately twelve years, the evolution of the guitar amplifier has largely been pioneered by MESA-Boogie. The Original Mark I Boogie was the first amplifier to offer successful lead enhancement. Then the Mark II Boogie was the first amplifier to introduce footswitching between lead and rhythm. Now your new Mark III offers three footswitchable modes of operation: Rhythm 1, Rhythm 2 and Lead. Rhythm 1 is primarily for playing bright and sparkling clean (although a little crunch is available by running the Volume at 10). You might think of Rhythm 1 as "the Fender mode”. Rhythm 2 is mainly for crunch chords, chunking metal patterns and some blues (but low settings of the Volume 1 will produce an alternate clean sound that is very fat and warm). Think of Rhythm 2 as "the Marshall mode". -

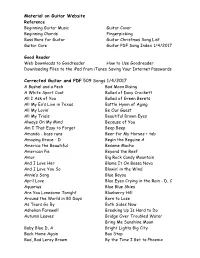

1Guitar PDF Songs Index

Material on Guitar Website Reference Beginning Guitar Music Guitar Cover Beginning Chords Fingerpicking Bass Runs for Guitar Guitar Christmas Song List Guitar Care Guitar PDF Song Index 1/4/2017 Good Reader Web Downloads to Goodreader How to Use Goodreader Downloading Files to the iPad from iTunes Saving Your Internet Passwords Corrected Guitar and PDF 509 Songs 1/4/2017 A Bushel and a Peck Bad Moon Rising A White Sport Coat Ballad of Davy Crockett All I Ask of You Ballad of Green Berets All My Ex’s Live in Texas Battle Hymn of Aging All My Lovin’ Be Our Guest All My Trials Beautiful Brown Eyes Always On My Mind Because of You Am I That Easy to Forget Beep Beep Amanda - bass runs Beer for My Horses + tab Amazing Grace - D Begin the Beguine A America the Beautiful Besame Mucho American Pie Beyond the Reef Amor Big Rock Candy Mountain And I Love Her Blame It On Bossa Nova And I Love You So Blowin’ in the Wind Annie’s Song Blue Bayou April Love Blue Eyes Crying in the Rain - D, C Aquarius Blue Blue Skies Are You Lonesome Tonight Blueberry Hill Around the World in 80 Days Born to Lose As Tears Go By Both Sides Now Ashokan Farewell Breaking Up Is Hard to Do Autumn Leaves Bridge Over Troubled Water Bring Me Sunshine Moon Baby Blue D, A Bright Lights Big City Back Home Again Bus Stop Bad, Bad Leroy Brown By the Time I Get to Phoenix Bye Bye Love Dream A Little Dream of Me Edelweiss Cab Driver Eight Days A Week Can’t Help Falling El Condor Pasa + tab Can’t Smile Without You Elvira D, C, A Careless Love Enjoy Yourself Charade Eres Tu Chinese Happy -

The Money Band Songlist

THE MONEY BAND SONGLIST 50s Bobby Darin Mack the Knife Somewhere Beyond the Sea Ben E King Stand By Me Carl Perkins Blue Suede Shoe Elvis Presley Heartbreak Hotel Hound Dog Jailhouse Rock Frank Sinatra Fly Me To The Moon Johnny Cash Folsom Prison Blues Louis Armstrong What A Wonderful World Ray Charles I Got A Woman Wha’d I Say 60s Beach Boys Surfing USA Beatles Birthday Michelle Norwegian Wood I Feel Fine I Saw Her Standing There Bobby Darin Dream Lover Chantays Pipeline Chuck Berry Johnny B Good Dick Dale Miserlou Wipe Out Elvis Presley All Shook Up Can’t Help Falling In Love Heartbreak Hotel It’s Now or Never Little Less Conversation Little Sister Suspicious Minds Henri Mancini Pink Panther Jerry Lee Lewis Great Balls of Fire Whole Lotta Shakin Jimi Hendrix Fire Hey Joe Wind Cries Mary Johnny Rivers Secret Agent Man Johnny Cash Ring of Fire Kingsmen Louie Louie Otis Redding Dock of the Bay Ricky Nelson Hello Marylou Traveling Man Rolling Stones Paint It Black Jumping Jack Flash Satisfaction Cant Always Get What You Want Beast of Burden Sam the Sham & the Pharaohs Wooly Bully Tommy James Mony Mony Troggs Wild Thing Van Morrison Baby Please Don’t Go Brown Eyed Girl Into The Mystic The Who My Generation 70s Beatles Get Back Imagine Something Bee Gees You Should Be Dancing Staying Alive Carl Douglas Kung Foo Fighting Cat Stevens Wild World The Commodores Brick House David Bowie Rebel, Rebel Diana Ross Upside Down Donna Summer Hot Stuff Doors LA Woman Love Me Two Times Roadhouse Blues The Eagles Hotel California Elvis Presley Steamroller -

Ops Urged to Plan Ahead -- Page 4 I ..A

THE CONFIDENTIAL WEEKLY OF THE COIN MACHINE INDUSTR VOL. 11, NO. 49 SEPTEMBER 2, 1950 Rosemary Clooney, Columbia Records singing star, lends an ear while ace songwriter, Frank Loesser runs thru his new tune "Why Fight The Feeling?" currently getting quite a play from the operators. Rosemary Clooney records exclu- sively on Columbia Records. Personal Management: Joe Shribman. Ops Urged To Plan Ahead -- Page 4 I ..a... emstreeminigemluir t, e' ts .N'.b `gWURLITZERZ1ede MOST VERSATILE PHONOGRAPH EVER BUILT GIVES YOU THE MOST FLEXIBLE PROGRAMMING SYSTEM FOUND ON ANY JUKE BOX Standard sections for which classification cards can be provided are POPULAR TUNES, WALTZES, `FOLK PROGRAM NUMBERS, CLASSICS, WESTERNS and POLKAS. You can have eight tunes under each heading or you CLASSIFICATIONS can tailor your program to location requirements, de- voting any multiple of eight to any type of music, such as 16 PopularTunes,16 Westerns, 8 Polkas and 8 Waltzes. This programming on the Wurlitzer 1250 makes it 48 tunes on 24 records...enough to stimulate all-time more than ever the feature phonograph of the year- high play and keep record costs low. engineered in every way to attract the most play. The Wurlitzer 1250 proved THAT! See it in action at your Wurlitzer Distributors now. Get it in action on location and watch it "go to town" for you. In addition, the 1250 offers another great play -stimu- lating feature. All 1250 record selectors will play the top and bottom You can classify the 48 tunes on a Wurlitzer 1250 in WURLITZER up to SIX SECTIONS for quick, easy selection from MODEL 4820 a program "custom-built" for any location. -

Shoosh 800-900 Series Master Tracklist 800-977

SHOOSH CDs -- 800 and 900 Series www.opalnations.com CD # Track Title Artist Label / # Date 801 1 I need someone to stand by me Johnny Nash & Group ABC-Paramount 10212 1961 801 2 A thousand miles away Johnny Nash & Group ABC-Paramount 10212 1961 801 3 You don't own your love Nat Wright & Singers ABC-Paramount 10045 1959 801 4 Please come back Gary Warren & Group ABC-Paramount 9861 1957 801 5 Into each life some rain must fall Zilla & Jay ABC-Paramount 10558 1964 801 6 (I'm gonna) cry some time Hoagy Lands & Singers ABC-Paramount 10171 1961 801 7 Jealous love Bobby Lewis & Group ABC-Paramount 10592 1964 801 8 Nice guy Martha Jean Love & Group ABC-Paramount 10689 1965 801 9 Little by little Micki Marlo & Group ABC-Paramount 9762 1956 801 10 Why don't you fall in love Cozy Morley & Group ABC-Paramount 9811 1957 801 11 Forgive me, my love Sabby Lewis & the Vibra-Tones ABC-Paramount 9697 1956 801 12 Never love again Little Tommy & The Elgins ABC-Paramount 10358 1962 801 13 Confession of love Del-Vikings ABC-Paramount 10341 1962 801 14 My heart V-Eights ABC-Paramount 10629 1965 801 15 Uptown - Downtown Ronnie & The Hi-Lites ABC-Paramount 10685 1965 801 16 Bring back your heart Del-Vikings ABC-Paramount 10208 1961 801 17 Don't restrain me Joe Corvets ABC-Paramount 9891 1958 801 18 Traveler of love Ronnie Haig & Group ABC-Paramount 9912 1958 801 19 High school romance Ronnie & The Hi-Lites ABC-Paramount 10685 1965 801 20 I walk on Little Tommy & The Elgins ABC-Paramount 10358 1962 801 21 I found a girl Scott Stevens & The Cavaliers ABC-Paramount -

San Diego's Queen of the Boogie Woogie

by Put Kramer Sue Palmer Sun Diego's Qaeen of Boogie Woogie rflhirty years in lhe mustc Sue's first professional I indrrt.y is a long time band was in Tobacco Road, for any performer, particular- a band she formed with well ly for blues artists and espe- known jazz and swing bass cially for women blues per- player Preston Coleman. formers. For Sue Palmer, the Over the next 15 years, the "Queen of Boogie Woogie," band played regular gigs at it's been a star-studded blues the Belly Up Tavern in So- career with many rewards lano Beach. Of Coleman she and awards. The swing, blues says, "Working with Preston and boogie-woogie piano was like going to college to player has toured the world learn my craft. He was the and played music festivals real thing - a man who was throughout the U.S. and Eu- a fantastic performer and ar- rope as the pianist for blues ranger and was kind and gen- diva Candye Kane. But it's erous with us." her solo and band recording While fronting Tobacco as Sue Palmer and Her Mo- Road, Sue met Candye Kane tel Swing Orchestra that have and soon after the two be- generated the most awards. gan collaborating on music. Her fourth release, Sophisti- Later, Sue was invited to join cated Lady won an Interna- Kane's band as piano player tional Blues Challenge Award which led to world tours for "Best Self Produced CD" through the '90s playing club in 2008, her third release, dates and festivals in Canada, Live at Dizzy's won "Best Australia, France, Holland, Blues Album 200212003" the Netherlands and United and her solo piano album, States. -

Aint Gonna Study War No More / Down by the Riverside

The Danish Peace Academy 1 Holger Terp: Aint gonna study war no more Ain't gonna study war no more By Holger Terp American gospel, workers- and peace song. Author: Text: Unknown, after 1917. Music: John J. Nolan 1902. Alternative titles: “Ain' go'n' to study war no mo'”, “Ain't gonna grieve my Lord no more”, “Ain't Gwine to Study War No More”, “Down by de Ribberside”, “Down by the River”, “Down by the Riverside”, “Going to Pull My War-Clothes” and “Study war no more” A very old spiritual that was originally known as Study War No More. It started out as a song associated with the slaves’ struggle for freedom, but after the American Civil War (1861-65) it became a very high-spirited peace song for people who were fed up with fighting.1 And the folk singer Pete Seeger notes on the record “Waist Deep in the Big Muddy and Other Love Songs”, that: "'Down by the Riverside' is, of course, one of the oldest of the Negro spirituals, coming out of the South in the years following the Civil War."2 But is the song as we know it today really as old as it is claimed without any sources? The earliest printed version of “Ain't gonna study war no more” is from 1918; while the notes to the song were published in 1902 as music to a love song by John J. Nolan.3 1 http://myweb.tiscali.co.uk/grovemusic/spirituals,_hymns,_gospel_songs.htm 2 Thanks to Ulf Sandberg, Sweden, for the Pete Seeger quote. -

Marcina Kasiny Oleśnica – 04

TURNIEJ TAŃCA NOWOCZESNEGO o Puchar Wójta Gminy Oleśnica Marcina Kasiny Oleśnica – 04. lutego 2018 r. /niedziela/ 1. Organizator: 2. Współorganizatorzy: Polski Związek Tańca Freestyle Gmina Oleśnica Szkoła Tańca JAST JAST Atan Gminny Ośrodek Kultury Oleśnica 3. Termin imprezy: 04.02.2018 (niedziela) 4. Miejsce: Gminna Hala Sportowa, ul. Wileńska 32, 56 – 400 Oleśnica 5. Cele: - Popularyzacja i propagowanie tańca nowoczesnego. - Integracja Grup Tanecznych oraz instruktorów tańca. - Rywalizacja Fair Play oraz wspólna zabawa uczestników. - Wyłonienie najlepszych zespołów w poszczególnych kategoriach. - Promocja Gminy Oleśnica. - Promocja rywalizacji tanecznej wśród dzieci i młodzieży Gminy Oleśnica. 6. Komisja sędziowska: 5 licencjonowanych sędziów PZTF i skrutiner PZTF. 7. Kategorie wiekowe: Organizator zastrzega sobie możliwość połączenia kategorii wiekowych i dyscyplin tanecznych w przypadku 4 i mniej zespołów. 7 lat i młodsi (rocznik 2011 i młodsi 9 lat i młodsi (roczniki 2009 i młodsi) 11 lat i młodsi (roczniki 2007 i młodsi) 15 lat i młodsi (rocznik 2003 i młodsi) 16 lat i starsi (2002 i starsi) 31 lat i starsi (1987 i starsi) O przynależności do kategorii wiekowej w III, II i I lidze decyduje wiek najstarszego zawodnika – z tolerancją do 1 osoby. W Ekstralidze decyduje wiek najstarszego zawodnika UWAGA! W III, II i I lidze możliwe jest tańczenie jednej albo dwóch prezentacji przez ten sam zespół (oznacza to również, że jeden tancerz może występować w dwóch różnych zespołach danego klubu). Nazwa zespołu tańczącego dwie prezentacje musi kończyć się cyfrą 1 albo 2, np. JAST 1 i JAST 2 - nr 1 oznacza pierwszą prezentację w kolejności, nr 2 – drugą. 8. Muzyka: III , II i I Liga - muzyka własna do 3 min. -

Rhythm & Blues Rhythm & Blues S E U L B & M H T Y

64 RHYTHM & BLUES RHYTHM & BLUES ARTHUR ALEXANDER JESSE BELVIN THE MONU MENT YEARS CD CHD 805 € 17.75 GUESS WHO? THE RCA VICTOR (Baby) For You- The Other Woman (In My Life)- Stay By Me- Me And RECORD INGS (2-CD) CD CH2 1020 € 23.25 Mine- Show Me The Road- Turn Around (And Try Me)- Baby This CD-1:- Secret Love- Love Is Here To Stay- Ol’Man River- Now You Baby That- Baby I Love You- In My Sorrow- I Want To Marry You- In Know- Zing! Went The My Baby’s Eyes- Love’s Where Life Begins- Miles And Miles From Strings Of My Heart- Home- You Don’t Love Me (You Don’t Care)- I Need You Baby- Guess Who- Witch craft- We’re Gonna Hate Ourselves In The Morn ing- Spanish Harlem- My Funny Valen tine- Concerte Jungle- Talk ing Care Of A Woman- Set Me Free- Bye Bye Funny- Take Me Back To Love- Another Time, Another Place- Cry Like A Baby- Glory Road- The Island- (I’m Afraid) The Call Me Honey- The Migrant- Lover Please- In The Middle Of It All Masquer ade Is Over- · (1965-72 ‘Monument’) (77:39/28) In den Jahren 1965-72 Alright, Okay, You Win- entstandene Aufnahmen in seinem eigenwilligen Stil, einer Ever Since We Met- Pledg- Mischung aus Soul und Country Music / his songs were covered ing My Love- My Girl Is Just by the Stones and Beatles. Unique country-soul music. Enough Woman For Me- SIL AUSTIN Volare (Nel Blu Dipinto Di SWINGSATION CD 547 876 € 16.75 Blu)- Old MacDonald (The Dogwood Junc tion- Wildwood- Slow Walk- Pink Shade Of Blue- Charg ers)- Dandilyon Walkin’ And Talkin’- Fine (The Charg ers)- CD-2:- Brown Frame- Train Whis- Give Me Love- I’ll Never -

Texas A&M University at Galveston

TEXAS A&M UNIVERSITY AT GALVESTON Residence Hall Manual Revised: January 2016 TAMUG Residence Life Manual Page 0 Residence Life – 24 hour Phone Number: 409.740.4445 Howdy! On behalf of myself, the Hall Coordinators, Community Leaders and all of our staff, please let me welcome you to our community here at Texas A&M University at Galveston’s Mitchell Campus Residence Life. We are so excited to have you here during this time of scholarship. This is such an incredible time in your lives. Never again will you be exposed to such a cross- section of the world. We want you to take advantage of that. Meet people you would never meet. Put yourself in situations where you can learn, and don’t be afraid to take a chance and ask the crazy question! The answers may surprise us all. It is our mission to provide every student on campus with a place where they can safely live and learn. Past that, we seek to create an environment that fosters scholarship and encourages learning for the sake of learning. We as that you partner with us in building a community of Aggies that care and that embodies the ideals of the Aggie Code of Honor. We do not lie, cheat, steal nor tolerate those that do. We want to provide a safe environment where we can learn from each other through honest dialogues of difference. We know that our relationships are most successful when we communicate with intention in an earnest search to understand before being understood. We value those who stand up for the rights and well-being of others as well as for themselves. -

The Jody Williams Story

THE JODY WILLIAMS STORY Howlin’ Wolf, Jody Williams, Earl Phillips and Hubert Sumlin. Chicago circa mid 1950s. From the B&R Archives. Interview by Mike Stephenson y name is Joseph Leon Williams, that’s the styles because some of the people who were around also impressed me. People who I played with I’d pick up a little bit here and there because at that name my mother gave me. I’ve been called age I was trying to learn all I could. When I got started on guitar, Bo Diddley a little of everything over the years, but taught me how to tune the guitar to an open E. He taught me how to play the M bass background but his playing was limited, I wanted to learn more. I was Jody is a nickname. When I started recording, if hungry for knowledge on the guitar so I would hang around in the clubs and they had put Joe Williams on the record they might stuff like that. You could say I was getting on the job training. have confused me with the singer Joe Williams I started to come into contact with more and more people. I don’t recall how I got into the studio but I went to Chess Studios first around 1956. Willie Dixon who was with Count Basie! So people would have helped me. This is the guy who wrote many tunes, matter of fact he wrote the been buying his recordings thinking it was me and first tune that I recorded and he’s playing on it – ‘Lookin’ For My Baby’ (Blue Lake 116).