The Documentation of Nineteenth-Century Gardens: an Examination of the New Orleans Notarial Archives

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

City of New Orleans Residential Parking Permit (Rpp) Zones

DELGADO CITY PARK COMMUNITY COLLEGE FAIR GROUNDS ZONE 17 RACE COURSE ZONE 12 CITY OF NEW ORLEANS RESIDENTIAL PARKING E L Y PERMIT (RPP) ZONES S 10 I ¨¦§ A ES N RPP Zones Boundary Descriptions: PL F A I N E Zone 1: Yellow (Coliseum Square) AD L E D St. Charles Avenue / Pontchartrain Expwy / S AV Mississippi River / Jackson Avenue A T V S Zone 2: Purple (French Quarter) D North Rampart Street / Esplanade Avenue / A Mississippi River / Iberville Street O R TU B LA Zone 3: Blue NE ZONE 11 South Claiborne Avenue / State Street / V AV Willow Street / Broadway Street A C N AN O AL Zone 4: Red (Upper Audubon) T S LL T St. Charles Avenue / Audubon Street / O Leake Avenue / Cherokee Street R R A 10 Zone 5: Orange (Garden District) C ¨¦§ . S St. Charles Avenue / Jackson Avenue / ZONE 2 Constance Street / Louisiana Avenue Zone 6: Pink (Newcomb Blvd/Maple Area) Willow Street / Tulane University / St. Charles Avenue / South Carrollton Avenue Zone 7: Brown (University) Willow Street / State Street / St. Charles Avenue / Calhoun Street / Loyola University ZONE 18 Zone 9: Gold (Touro Bouligny) ZONE 14 St. Charles Avenue / Louisiana Avenue / Magazine Street / Napoleon Avenue ZONE 3 AV Zone 10: Green (Nashville) NE St. Charles Avenue / Arabella Street / ZONE 6 OR Prytania Street / Exposition Blvd IB LA C Zone 11: Raspberry (Faubourg Marigny) S. TULANE St. Claude Avenue / Elysian Fields Avenue / UNIVERSITY ZONE 16 Mississippi River / Esplanade Avenue ZONE 15 Zone 12: White (Faubourg St. John) DeSaix Blvd / St. Bernard Avenue / LOYOLA N North Broad Street / Ursulines Avenue / R UNIVERSITY A Bell Street / Delgado Drive ZONE 7 P O E L Zone 13: Light Green (Elmwood) E AV ZONE 1 Westbank Expwy / Marr Avenue / O ES V General de Gaulle Drive / Florence Avenue / N L ZONE 4 R Donner Road A HA I V . -

Appraisal of Former Audubon School/ Carrollton Courthouse Property 719 South Carrollton Avenue New Orleans, Louisiana70118

APPRAISAL OF FORMER AUDUBON SCHOOL/ CARROLLTON COURTHOUSE PROPERTY 719 SOUTH CARROLLTON AVENUE NEW ORLEANS, LOUISIANA70118 FOR MR. LESLIE J. REY EXECUTIVE DIRECTOR PURCHASING/ANCILLARY SERVICES & TRANSPORTATION 3520 GENERAL DE GAULLE DRIVE 5TH FLOOR, ROOM 5078 NEW ORLEANS, LOUISIANA 70053 BY HENRY W. TATJE, III ARGOTE, DERBES & TATJE, LLC REPORT DATE 512 N. CAUSEWAY BLVD NOVEMBER 28, 2016 METAIRIE, LA 70001 504.830.3864 DIRECT LINE OUR FILE NUMBER 504.830.3870 FAX 16-296.003 ARGOTE, DERBES & TATJE, LLC. REAL ESTATE APPRAISAL & COUNSELING 512 N. Causeway Boulevard Metairie, Louisiana 70001 Direct Line: (504) 830-3864 Email: [email protected] November 28, 2016 Our File No. 16-0296.003 Mr. Leslie J. Rey Executive Director Purchasing/Ancillary Services & Transportation 3520 General De Gaulle Drive 5th Floor, Room 5078 New Orleans, Louisiana 70114 RE: Appraisal of Former Audubon School/Carrollton Courthouse Property 719 South Carrollton Avenue New Orleans, Louisiana 70118 Owner: Orleans Parish School Board Dear Mr. Rey: In accordance with your request, I have prepared a real property appraisal of the above-referenced property, presented in a summary appraisal report format. This appraisal report sets forth the most pertinent data gathered, the techniques employed, and the reasoning leading to my opinion of the current market value of the Unencumbered Fee Simple Interest in and to the appraised property in current “As Is Condition”. Market Value, as used herein, is defined as: "The most probable price which a property should bring in a competitive and open market under all conditions requisite to a fair sale, the buyer and seller each acting prudently and knowledgeably, and assuming the price is not affected by undue stimulus." The property rights appraised is the Unencumbered Fee Simple Interest which is defined as: “an absolute fee; a fee without limitations to any particular class of heirs or restrictions, but subject to the limitations of eminent domain, escheat, police power, and taxation. -

Bayou Boogaloo Authentic Cajun & Creole Cuisine

120 West Main Street, Norfolk, Virginia 23510 P: 757.441.2345 • W: festevents.org • E: [email protected] Media Release Media Contact: Erin Barclay For Immediate Release [email protected] P: 757.441.2345 x4478 Nationally Known New Orleans Chefs Serve Up Authentic Cajun & Creole Cuisine at 25th Annual Bayou Boogaloo and Cajun Food Festival presented by AT&T Friday, June 20 – Sunday, June 22, 2014 Town Point Park, Downtown Norfolk Waterfront, VA • • • NORFOLK, VA – (May 27, 2014) – Nothing says New Orleans like the uniquely delicious delicacies and distinctive flavor of Cajun & Creole cuisine! Norfolk Festevents is bringing nationally known chefs straight from New Orleans to Norfolk to serve up the heart and soul of Louisiana food dish by dish at the 25th Annual AT&T Bayou Boogaloo & Cajun Food Festival starting Friday, June 20- Sunday, June 22, 2014 in Town Point Park in Downtown Norfolk, VA. Norfolk’s annual “second line” with New Orleans’ unique culture spices it up this year with the addition of multiple New Orleans chefs that are sure to bring that special spirit to life in Town Point Park. Cooking up their famous cajun & creole cuisines are Ms. Linda The Ya-ka-Mein Lady, Chef Curtis Moore from the Praline Connection, Chef Woody Ruiz, New Orleans Crawfish King Chris “Shaggy” Davis, Jacques-Imo’s Restaurant, Edmond Nichols of Direct Select Seafood, Chef Troy Brucato, Cook Me Somethin’ Mister Jambalaya and more! They have been featured on such television shows as Anthony Bourdain’s “No Reservations”, Food Networks highly competitive cooking competition “Chopped”, “Food Paradise” and “The Best Thing I Ever Ate”. -

Posted on May 5, 2021 Sites with Asterisks (**) Are Able to Vaccinate 16-17 Year Olds

Posted on May 5, 2021 Sites with asterisks (**) are able to vaccinate 16-17 year olds. Updated at 4:00 PM All sites are able to vaccinate adults 18 and older. Visit www.vaccinefinder.org for a map of vaccine sites near you. Parish Facility Street Address City Website Phone Acadia ** Acadia St. Landry Hospital 810 S Broadway Street Church Point (337) 684-4262 Acadia Church Point Community Pharmacy 731 S Main Street Church Point http://www.communitypharmacyrx.com/ (337) 684-1911 Acadia Thrifty Way Pharmacy of Church Point 209 S Main Street Church Point (337) 684-5401 Acadia ** Dennis G. Walker Family Clinic 421 North Avenue F Crowley http://www.dgwfamilyclinic.com (337) 514-5065 Acadia ** Walgreens #10399 806 Odd Fellows Road Crowley https://www.walgreens.com/covid19vac Acadia ** Walmart Pharmacy #310 - Crowley 729 Odd Fellows Road Crowley https://www.walmart.com/covidvaccine Acadia Biers Pharmacy 410 N Parkerson Avenue Crowley (337) 783-3023 Acadia Carmichael's Cashway Pharmacy - Crowley 1002 N Parkerson Avenue Crowley (337) 783-7200 Acadia Crowley Primary Care 1325 Wright Avenue Crowley (337) 783-4043 Acadia Gremillion's Drugstore 401 N Parkerson Crowley https://www.gremillionsdrugstore.com/ (337) 783-5755 Acadia SWLA CHS - Crowley 526 Crowley Rayne Highway Crowley https://www.swlahealth.org/crowley-la (337) 783-5519 Acadia Miller's Family Pharmacy 119 S 5th Street, Suite B Iota (337) 779-2214 Acadia ** Walgreens #09862 1204 The Boulevard Rayne https://www.walgreens.com/covid19vac Acadia Rayne Medicine Shoppe 913 The Boulevard Rayne https://rayne.medicineshoppe.com/contact -

Mid-City Market 401 North Carrollton Avenue New Orleans, Louisiana

MID-CITY MARKET 401 North Carrollton Avenue NEW ORLEANS, LoUISIANA WWW.STIRLINGPROPERTIES.COM OVERVIEW MAPS SITE PLAN AERIALS AREA INFO DEMOGRAPHICS ------------------------------------OVERVIEW Located along North Carrollton Avenue in New Orleans, Louisiana, Mid-City Market will serve as the retail and restaurant center of the community. Grocery anchored by a new Winn-Dixie Supermarket, the site will feature both small shop retail and restaurant space, as well as the scarce opportunity for Junior Anchors to gain access to Orleans Parish. The Mid-City area has continued to thrive since Hurricane Katrina with stable demographics and income base. The oak-lined area has long been a local favorite for restaurants, coffee shops, retail, service and recreation. The addition of the BioDistrict to Mid-City will further help to bring additional people and jobs and include a new VA Hospital, Univeristy Medical Center, Lousiana Cancer Research Center, and BioInovations . The over 2 billion dollar campus-style facility is currently under construction and slated to open in 2013 and employ collectively more than 5,500 permanent jobs in the first 5 years it is in service. Over a 10 year period, this project will bring approximately 13,400 total jobs to Mid-City. New Orleans was recently named one of the 7 Cities that have Caught “Start-Up Fever” by Details Magazine. The area also was named atop of Forbes and New Geography’s list of “Brain Gain Magnets” where recent college graduates are taking their degrees. ------------------------------------AVAILABILITY ▪ Space Available: 1,000 - 28,000 SF ▪ Total Square Footage Available: 54,216 SF ------------------------------------SPACE DELIVERY ▪ August 2012 ------------------------------------AREA RETAILERS ▪ Home Depot ▪ Rouses Supermarket ▪ Nike Factory Outlet Store ▪ Walgreens The foregoing is solely for information purposes and is subject to change without notice. -

IDB Cover.Indd

Past Projects A Message From Our President MTW Investments – $1.6M - 701 Julia Street - 757-59 Greetings: St. Charles Avenue HEG, Inc. – 1983 - $3.5M This is our fi rst annual report since Hurricane Katrina, a hurricane 926 –36 Common Street which dealt our City a terrible blow. The City of New Orleans is now Blvd. Enterprises - $1M faced with participating in its own metamorphosis – not by choice JR Miller – $5.7M - KFC’s (9 locations) but by happenstance – a catastrophic happenstance. We all must 601 St. Charles Partnership – $3M - 601-25 St. Charles Avenue now look at rebuilding our City in creative and daring ways. We, Mid-City Self Storage – $2.5M - 3440 S. Carrollton Avenue the members of the Industrial Development Board of the City of The Mills (Federal Fiber) – $10M New Orleans, Louisiana Inc. are committed to this challenge and opportunity. We know that we must not only look at rebuilding Pritchard Place Partnership - $750K - 600 Julia Street New Orleans, bringing our citizens back to homes and jobs but we SFE Technologies – $7.8M - 4100 Michoud Boulevard must also look at creating economic development that contributes Natchez Properties – $1.8M - 526-32 Natchez Street to the City’s future growth with courage and conviction. Today, Jimmie Thorns Jr. this is the mission of the Industrial Development Board. As New President 1981 Orleanians, we are on the threshold of putting New Orleans back FLA Property – $1.5M 527 Tchoupitoulas Street on the map bigger and better than before. 400 Lafayette Company – $2.6M The material that follows constitutes the work, efforts and contributions to our City by the members of the Family Inn – 6301 Chef Highway Industrial Development Board. -

MULTIFAMILY for SALE Uptown New Orleans - Next to Tulane University

MULTIFAMILY FOR SALE Uptown New Orleans - Next to Tulane University 6325-27 & 6331-35 S. Johnson 8 1 0 u n i o n S T R E E T , N E W O R L E A N S , L A 7 0 1 1 2 5 0 4 - 2 7 4 - 2 7 0 1 | M C E N E R Y C O . C O M Offering overview Address: 6325-27 & 6331-35 S. Johnson, New Orleans, LA 70118 Price: $525,000 (6325-27 S. Johnson) | $485,000 (6331-35 S. Johnson) Property Overview: Extremely rare multifamily opportunity adjacent to Tulane Campus. Two buildings consisting of three units each. Located on S. Johnson St., the properties share a property line with Tulane's Campus providing immediate access to the University and surrounding area. 6331- 33 S Johnson is a One story structure consisting of 3 total units. It was renovated to the studs in 2012 including new systems, insulation, etc.. 6325-6327 S Johnson is a two story structure consisting of three total units. The downstairs was renovated to the Studs post Katrina. Covered, off-street parking in rear of the property. Impeccably maintained and 100% occupied. Properties can be purchased together or separately. TROY HAGSTETTE D: 504.582.9251 C: 504.251.5719 email: [email protected] The information contained herein has been obtained from sources that we deem reliable. No representation or warranty is made as to the accuracy thereof, and it is submitted subject to errors, omissions, change of price, or other conditions, or withdrawal without notice. -

Final Staff Report

CITY PLANNING COMMISSION CITY OF NEW ORLEANS MITCHELL J. LANDRIEU ROBERT D. RIVERS MAYOR EXECUTIVE DIRECTOR LESLIE T. ALLEY DEPUTY DIRECTOR City Planning Commission Staff Report Executive Summary Summary of Uptown and Carrollton Local Historic District Proposals: The Historic Preservation Study Committee Report of April 2016, recommended the creation of the Uptown Local Historic District with boundaries to include the area generally bounded by the Mississippi River, Lowerline Street, South Claiborne Avenue and Louisiana Avenue, and the creation of the Carrollton Local Historic District with boundaries to include the area generally bounded by Lowerline Street, the Mississippi River, the Jefferson Parish line, Earhart Boulevard, Vendome Place, Nashville Avenue and South Claiborne Avenue. These partial control districts would give the Historic District Landmarks Commission (HDLC) jurisdiction over demolition. Additionally, it would give the HDLC full control jurisdiction over all architectural elements visible from the public right-of-way for properties along Saint Charles Avenue between Jena Street and South Carrollton Avenue, and over properties along South Carrollton Avenue between the Mississippi River and Earhart Boulevard. Recommendation: The City Planning Commission staff recommends approval of the Carrollton and Uptown Local Historic Districts as proposed by the Study Committee. Consideration of the Study Committee Report: City Planning Commission Public Hearing: The CPC holds a public hearing at which the report and recommendation of the Study Committee are presented and the public is afforded an opportunity to consider them and comment. City Planning Commission’s recommendations to the City Council: Within 60 days after the public hearing, the City Planning Commission will consider the staff report and make recommendations to the Council. -

Tulane Medical Center Saratoga St

From Covington/Mandeville or Metairie: ■ Take I-10 East following the New Orleans signs. ■ Exit right at the Claiborne/Superdome Exit. ■ Follow signs to Claiborne East, going up onto the overpass, keeping to the right. ■ Go down Claiborne Avenue to Cleveland Avenue and turn right. ■ Travel three blocks to LaSalle St. and take a right. The LaSalle St. Parking Garage is on the right. CAMPUS ■ Or, travel five blocks on Cleveland to South Tulane Medical Center Saratoga St. and take a left. The South 1415 Tulane Avenue, New Orleans, LA 70112 Saratoga St. Parking Garage is on the left. From the Westbank: ■ Travel east across the Crescent City Connection over the Mississippi River. 504-988-5800 or ■ Take the Superdome Exit and turn right onto Cleveland Avenue. ■ Travel three blocks to LaSalle St. and take a 800-588-5800 right. The LaSalle St. Parking Garage is on the right. ■ Or, travel five blocks on Cleveland to South Tulane LaSalle Street Parking Garage Saratoga St. and take a left. The South at 275 LaSalle Street between Tulane Avenue and Cleveland is open 24 hours Saratoga St. Parking Garage is on the left. daily. The garage is connected to the second-floor level of Tulane Medical Center, where outpatient Lab/Radiology registration and admitting are also located. From New Orleans East/Slidell: Tulane’s Multispecialty Center is located on the first floor of the parking garage, ■ Follow I-10 West to the Canal and the Medical Center’s Emergency Department is across the street from the Street/Superdome Westbank Exit. garage entrance. -

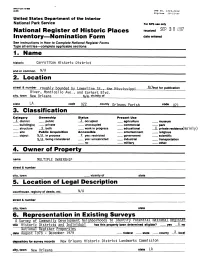

National Register Off Historic Places Inventory—Nomination Form 1

NFS Form 10-900 (3-82) OMB No. 1024-0018 Expires 10-31-87 United States Department of the Interior National Park Service For NPS use only National Register off Historic Places received SEP 3 0 J987 Inventory—Nomination Form date entered See instructions in How to Complete National Register Forms Type all entries—complete applicable sections 1. Name historic Carrollton Historic District and or common N/A 2. Location street & number roughly bounded by Lower! ine .St., thP MJQs-j«;<nppi Jl/Anot for publication River, Monticello Ave., and Earhart Blvd. city, town New Orleans__________N/A- vicinity of state LA code 022 county Orleans Parish code 071 3. Classification Category Ownership Status Present Use _ X_ district public X occupied agriculture museum building(s) private unoccupied commercial park structure X both work in progress educational _JL private residence! mainly) site Public Acquisition Accessible entertainment religious object N/A in process -,X -yes: restricted government scientific N/A being considered - yes: unrestricted industrial transportation no military __ other: 4. Owner off Property name MULTIPLE OWNERSHIP street & number city, town vicinity of state 5. Location off Legal Description courthouse, registry of deeds, etc. N/A street & number city, town state 6. Representation in Existing Surveys A Survey of Community Development^ Neighborhoods to Identity Potential National Kegister title Historic Districts and Individual has this property been determined eligible? __ yes _X_no National Register Properties date August 1978 - December 1979 ________________ ___ federal __ state __ county __L local depository for survey records New Orleans Historic District Landmarks Commission _______ _ city, town New Orleans ___________________________ »tate LA__________ 7. -

A Season in Town: Plantation Women and the Urban South, 1790-1877

Western University Scholarship@Western Electronic Thesis and Dissertation Repository 8-23-2011 12:00 AM A Season in Town: Plantation Women and the Urban South, 1790-1877 Marise Bachand University of Western Ontario Supervisor Margaret M.R. Kellow The University of Western Ontario Graduate Program in History A thesis submitted in partial fulfillment of the equirr ements for the degree in Doctor of Philosophy © Marise Bachand 2011 Follow this and additional works at: https://ir.lib.uwo.ca/etd Part of the Women's History Commons Recommended Citation Bachand, Marise, "A Season in Town: Plantation Women and the Urban South, 1790-1877" (2011). Electronic Thesis and Dissertation Repository. 249. https://ir.lib.uwo.ca/etd/249 This Dissertation/Thesis is brought to you for free and open access by Scholarship@Western. It has been accepted for inclusion in Electronic Thesis and Dissertation Repository by an authorized administrator of Scholarship@Western. For more information, please contact [email protected]. A SEASON IN TOWN: PLANTATION WOMEN AND THE URBAN SOUTH, 1790-1877 Spine title: A Season in Town: Plantation Women and the Urban South Thesis format: Monograph by Marise Bachand Graduate Program in History A thesis submitted in partial fulfillment Of the requirements for the degree of Doctor of Philosophy The School of Graduate and Postdoctoral Studies The University of Western Ontario London, Ontario, Canada © Marise Bachand 2011 THE UNIVERSITY OF WESTERN ONTARIO School of Graduate and Postdoctoral Studies CERTIFICATE OF EXAMINATION Supervisor Examiners ____________________ ____________________ Dr. Margaret M.R. Kellow Dr. Charlene Boyer Lewis ____________________ Dr. Monda Halpern ____________________ Dr. Robert MacDougall ____________________ Dr. -

PDF (1.53 Mib)

NEWS The Tulane Hullabaloo • October 1, 1999 • 7 Rock the CASA parties for a cause Louisiana: Adrienne Gregory are volunteers and they want to be there helpmg upperclassmen to get together," said Kappa Alpha Theta advisor Emily Henderson. co11tributi11g 1,c.1riter the children. no one ends up as just a file or that one case a worker has to address before Last year around one thousand people Tulane recruits in-state going home in the afternoon. attended the 「 ・ ョ セ ヲ ゥ エ concert and, according to Kappa Alpha Theta will host the eighth contirrned.from page 1 keep a minimum 3.0 GPA and annual Rock the CASA party next Thursday, Gwen Alcus, special project coordinator Henderson, eight hundred of them were college for CASA New Orleans, said she became students. Tickets. which will be $12 in advance continuous enrollment in the Oct. 7. This year's benefit concert begins at 9 for Louisiana students. University. involved with CASA because it is a needed and $15 at the door. can be obtained from the p.m. at Tipitina 's Uptown. There will also be One new scholarship that will service. "Especially in this area, there is a high booth in the UC or by calling Tipitina's to The Tulane Book Award is a pre party tonight at the Boot at 9:30 p.m. only be available to entering another feature of this new with local band Tom's House. Proceeds from amount ofjuvenile delmquency. If we can catch reserve them. Shirts for the event were designed freshman i.; the Louisiana Scholars, recruitment program.