DISTRIBUTION of IROQUOIAN DISCOIDAL CLAY BEADS James F. Pendergast ABSTRACT Following an Extensive Search of the Literature Invo

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

7 Great Pottery Projects

ceramic artsdaily.org 7 great pottery projects | Second Edition | tips on making complex pottery forms using basic throwing and handbuilding skills This special report is brought to you with the support of Atlantic Pottery Supply Inc. 7 Great Pottery Projects Tips on Making Complex Pottery Forms Using Basic Throwing and Handbuilding Skills There’s nothing more fun than putting your hands in clay, but when you get into the studio do you know what you want to make? With clay, there are so many projects to do, it’s hard to focus on which ones to do first. So, for those who may wany some step-by-step direction, here are 7 great pottery projects you can take on. The projects selected here are easy even though some may look complicated. But with our easy-to-follow format, you’ll be able to duplicate what some of these talented potters have described. These projects can be made with almost any type of ceramic clay and fired at the recommended temperature for that clay. You can also decorate the surfaces of these projects in any style you choose—just be sure to use food-safe glazes for any pots that will be used for food. Need some variation? Just combine different ideas with those of your own and create all- new projects. With the pottery techniques in this book, there are enough possibilities to last a lifetime! The Stilted Bucket Covered Jar Set by Jake Allee by Steve Davis-Rosenbaum As a college ceramics instructor, Jake enjoys a good The next time you make jars, why not make two and time just like anybody else and it shows with this bucket connect them. -

Pottery Pieces Designed & Handmade in Our Ceramic Studios and Fired in Our Kilns

GLAZES ACCESSORIES FOUNTAINS PLANTERS & URNS OIL JARS ORNAMENTAL PIECES BIRDBATHS INTRODUCTION TERY est. 1875 Gladding, McBean & Co. POT Over A Century Of Camanship In Clay INTRODUCTION artisan made This catalog shows the wide range of pottery pieces designed & handmade in our ceramic studios and fired in our kilns. These pieces are not only for the garden, but also for general use of decoration indoors and out. Gladding, McBean & Co. has been producing this pottery for 130 years. Its manufacture began in the earliest years of the company’s existence at a time when no other terra cotta plant on the Pacific Coast was attempting anything of the sort. Gladding, McBean & Co. therefore, has pioneered in pottery-making. The company feels that it has carried the art to an impressive height of excellence. In every detail but color the following photographs speak for themselves. Each piece is glazed in one of our beautiful proprietary glazes. A complete set of glaze samples can be seen at our retail showrooms. This pottery is on display at, and may be ordered from, any of the retail showrooms listed on our website at www.gladdingmcbean.com. In photographing the pieces, and in reproducing the photographs for this catalog, the strictist care was taken to make the pictures as faithful as possible to the objects themselves. We are confident that in every instance the pottery will be found lovelier than its picture. The poet might well have had this pottery in mind when he wrote: “A thing of beauty is a joy forever.” BIRDBATHS no. 1099 birdbath width: 15.5” height: 24.5” base: 10” Birdbath no. -

Ch. 4. NEOLITHIC PERIOD in JORDAN 25 4.1

Borsa di studio finanziata da: Ministero degli Affari Esteri di Italia Thanks all …………. I will be glad to give my theses with all my love to my father and mother, all my brothers for their helps since I came to Italy until I got this degree. I am glad because I am one of Dr. Ursula Thun Hohenstein students. I would like to thanks her to her help and support during my research. I would like to thanks Dr.. Maysoon AlNahar and the Museum of the University of Jordan stuff for their help during my work in Jordan. I would like to thank all of Prof. Perreto Carlo and Prof. Benedetto Sala, Dr. Arzarello Marta and all my professors in the University of Ferrara for their support and help during my Phd Research. During my study in Italy I met a lot of friends and specially my colleges in the University of Ferrara. I would like to thanks all for their help and support during these years. Finally I would like to thanks the Minister of Fournier of Italy, Embassy of Italy in Jordan and the University of Ferrara institute for higher studies (IUSS) to fund my PhD research. CONTENTS Ch. 1. INTRODUCTION 1 Ch. 2. AIMS OF THE RESEARCH 3 Ch. 3. NEOLITHIC PERIOD IN NEAR EAST 5 3.1. Pre-Pottery Neolithic A (PPNA) in Near east 5 3.2. Pre-pottery Neolithic B (PPNB) in Near east 10 3.2.A. Early PPNB 10 3.2.B. Middle PPNB 13 3.2.C. Late PPNB 15 3.3. -

A Comparative Study of the Swennes Woven Nettle Bag and Weaving Techniques

Karoll UW-L Journal of Undergraduate Research XII (2009) A Comparative Study of the Swennes Woven Nettle Bag and Weaving Techniques Amy Karol Faculty Sponsors: Dr. Connie Arzigian and Dr. David Anderson, Department of Sociology and Archaeology ABSTRACT During recent years, the Mississippi Valley Archaeology Center (MVAC) has acquired permission to look at a beautifully preserved bag from 47Lc84, a rockshelter located in La Crosse County, Wisconsin. The bag is tentatively dated to the Oneota cultural tradition (A.D. 1250-1650) based on pottery sherds associated with it. Nothing of its kind has been found archaeologically in this region before, owing mostly to poor preservation conditions. Due to its uniqueness, there is nothing to compare it to within the Oneota tradition. Therefore, to gain a better understanding of this bag, a cross-cultural study was undertaken. This paper examines separate sites in the American Midwest, as well as textile impressions that are preserved on pottery, the ethnohistoric and early historic record, and modern hand-weaving techniques to determine the textile tradition from which the bag may have emerged as well as how it was constructed. INTRODUCTION Textiles in the archaeological record are poorly preserved in the American Midwest. Only in very few sites are they actually found, and in even fewer are the fragments large enough to be studied in depth. Detailed studies conducted on textiles are not numerous. Lacking in these studies is a cross-cultural comparison of types and materials from sites that do have better preserved textiles to try and determine similarities and differences in textile manufacture. -

Outdoor Pottery Sculpture in Ife Art School

E-ISSN 2281-4612 Academic Journal of Interdisciplinary Studies Vol 4 No 3 ISSN 2281-3993 MCSER Publishing, Rome-Italy November 2015 Outdoor Pottery Sculpture in Ife Art School Moses Akintunde Akintonde1 Toyin Emmanuel Akinde2 Segun Oladapo Abiodun3 Michael Adeyinka Okunade4 1,2,3 Department of Fine and Applied Arts, Ladoke Akintola University of Technology, Ogbomoso, Nigeria 4Department of Fine Arts, Obafemi Awolowo University, Ile-Ife, Nigeria; [email protected] [email protected], [email protected], [email protected] Doi:10.5901/ajis.2015.v4n3p219 Abstract The rich public outdoor sculpture practice of the Southwest of Nigeria still lacks scientific and empirical experimentation of non- conventional material for the production of outdoor sculpture, particularly pottery images. Although scholarship on public outdoor sculpture in the Southwest of Nigeria is becoming steady in growth, yet a reconnaissance study of the pottery sculpture in art practice and historical perspective has not been made. A study of this type of art, erected in the garden of Ife art school is exigent and paramount now that many of the works are not being maintained. The study underscores the inherent values in the genre of the art; and examined pottery sculpture types, its uses in public sphere and its development in morphology, iconic thematic and stylistic expressions. The study observed that outdoor pottery sculptures are impressive, apparent in sculpture multiplicity of type and dynamics; it is rare in occurrence in Southwestern Nigeria. Keywords: Ife Art School; outdoor sculpture, pottery sculpture; handbuilt pottery; Yoruba pottery. 1. Introduction The praxes of outdoor sculpture in Nigeria, beginning from the first quarter of twentieth century presented different latitudes. -

Redalyc.Toolkits and Cultural Lexicon: an Ethnographic

Indiana ISSN: 0341-8642 [email protected] Ibero-Amerikanisches Institut Preußischer Kulturbesitz Alemania Andrade Ciudad, Luis; Joffré, Gabriel Ramón Toolkits and Cultural Lexicon: An Ethnographic Comparison of Pottery and Weaving in the Northern Peruvian Andes Indiana, vol. 31, 2014, pp. 291-320 Ibero-Amerikanisches Institut Preußischer Kulturbesitz Berlin, Alemania Available in: http://www.redalyc.org/articulo.oa?id=247033484009 How to cite Complete issue Scientific Information System More information about this article Network of Scientific Journals from Latin America, the Caribbean, Spain and Portugal Journal's homepage in redalyc.org Non-profit academic project, developed under the open access initiative Toolkits and Cultural Lexicon: An Ethnographic Comparison of Pottery and Weaving in the Northern Peruvian Andes Luis Andrade Ciudad and Gabriel Ramón Joffré Ponticia Universidad Católica del Perú, Lima, Perú Abstract: The ndings of an ethnographic comparison of pottery and weaving in the Northern Andes of Peru are presented. The project was carried out in villages of the six southern provinces of the department of Cajamarca. The comparison was performed tak- ing into account two parameters: technical uniformity or diversity in ‘plain’ pottery and weaving, and presence or absence of lexical items of indigenous origin – both Quechua and pre-Quechua – in the vocabulary of both handicraft activities. Pottery and weaving differ in the two observed domains. On the one hand, pottery shows more technical diver- sity than weaving: two different manufacturing techniques, with variants, were identied in pottery. Weaving with the backstrap loom ( telar de cintura ) is the only manufacturing tech- nique of probable precolonial origin in the area, and demonstrates remarkable uniformity in Southern Cajamarca, considering the toolkit and the basic sequence of ‘plain’ weaving. -

Mass Cannibalism in the Linear Pottery Culture at Herxheim

Mass cannibalism in the Linear Pottery Culture at Herxheim (Palatinate, Germany) Bruno Boulestin1, Andrea Zeeb-Lanz2, Christian Jeunesse3, Fabian Haack2, Rose-Marie Arbogast3 & Anthony Denaire3,4 The Early Neolithic central place at Herxheim is defined by a perimeter of elongated pits containing fragments of human bone, together with pottery imported from areas several hundred kilometres distant. This article offers a context for the centre, advancing strong evidence that the site was dedicated to ritual activities in which cannibalism played an important part. Keywords: Europe, Germany, Linearbandkeramik pottery, LBK, human bone, cannibalism, butchering Introduction Since the early 1990s, archaeological and anthropological research into violence and war has become increasingly dynamic. The number of recent publications on the subject confirms this growing interest, for instance in the theoretical basis for the understanding of violence and war, and their relationships with social structures (Haas 1990; Reyna & Downs 1994; Keeley 1996; Martin & Frayer 1997; Carman & Harding 1999; Kelly 2000; Guilaine & Zammit 2001; Leblanc & Register 2003; Arkush & Allen 2006). The Neolithic of the Old World plays a particularly important part in this debate. While the problem of Neolithic violence was already tackled in early archaeological papers, it has recently been re-activated (Keeley 1996; Carman & Harding 1999; Guilaine & Zammit 2001; Beyneix 2001, 2007; Thorpe 2003; Christensen 2004; Pearson & Thorpe 2005; Schulting & Fibiger 2008), and debates about the importance of violence during the Neolithic, and how it should be qualified (should we speak of war?) remain heated. In particular, several discoveries made in Germany and Austria in the past 30 years raise the question of the reality of a climate of collective violence as early as the beginning of the Neolithic, that is at the end of the Linear Pottery Culture (end of the sixth millennium cal BC). -

Creative Beads Embellishment on Ceramic Wares in Nigeria

IOSR Journal Of Humanities And Social Science (IOSR-JHSS) Volume 19, Issue 10, Ver. II (Oct. 2014), PP 09-12 e-ISSN: 2279-0837, p-ISSN: 2279-0845. www.iosrjournals.org Creative Beads Embellishment on Ceramic Wares in Nigeria Okewu Ebute Jonathan 1* Deborah Ebute Jonathan2 1Department of Visual and Creative Arts, Federal University Lafia, Nasarawa State 2Department of Industrial Design, University of Maiduguri, Borno State Abstract: Conventional products are often decorated by incision, stamping, embossment, sprigging, graffito and glazing. However, some pieces are often marred by the kind of finishing that are given to them, particularly, inappropriate glazes. Therefore, the introduction of beads on ceramics wares might be a remedy to cushion the problem. The experimental process of this study went through the sourcing and processing of materials which include: Clay and kaolin collection, beneficiating the materials, production on the potter's wheel and drying, bisque and glaze firing. While the beads design entailed collecting assorted colours of beads and strand, passing the strands through the beads and finally hanging on the ceramics vases in a creative manner. Bead design on ceramic ware added value and enhanced the texture and aesthetic qualities of the products produced. This is a pointer to the fact that other non-conventional materials could be explored for such products to inspire and educate producers to increase creativity. Keywords: Creative, mix media, beads, glaze, ceramics I. Introduction Ceramics and Fashion design belong to the industrial design field and this field is more importantly concerned with the development of products which range from that of utility to decoration. -

Mehrgarh Neolithic

Paper presented in the International Seminar on the "First Farmers in Global Perspective', Lucknow, India, 18-20 January, 2006 Mehrgarh Neolithic Jean-Fran¸ois Jarrige From 1975 to 1985, the French Archaeological had already provided a summary of the main results Mission, in collaboration with the Department of brought by the excavations conducted from 1977 Archaeology of Pakistan, has conducted excavations to 1985 in the Neolithic sector of Mehrgarh. in a wide archaeological area near to the modern From 1985 to 1996, the excavations at Mehrgarh village of Mehrgarh in Balochistan at the foot of the were stopped and the French Mission undertook the Bolan Pass, one of the major communication routes excavation of a mound close to the village of between the Iranian Plateau, Central Asia and the Nausharo, 6 miles South of Mehrgarh. This excavation Indus Valley. showed clearly that the mound of Nausharo had Mehrgarh is located in the Bolan Basin, in the north- been occupied from 3000 to 2000 BC. After a western part of the Kachi-Bolan plain, a great alluvial Period I contemporary with Mehrgarh VI and VII, expanse that merges with the Indus Valley (Fig. 1). Periods II and III (c. 2500 to 2000 BC) at Nausharo The site itself is a vast area of about 300 hectares belong to the Indus (or Harappan) civilisation. covered with archaeological remains left by a Therefore the excavations at Nausharo allowed us to continuous sequence of occupations from the 8th to link in the Kachi-Bolan region, the Indus civilisation the 3rd millennium BC. to a continuous sequence of occupations starting from the aceramic Neolithic period. -

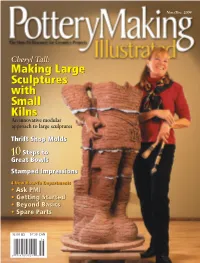

Making Large Sculptures with Small Kilns Thrift

PMI Nov_Dec 04 p0Cover 10/27/04 9:46 AM Page 1 Nov./Dec. 2004 Cheryl Tall: Making Large Sculptures with Small Kilns An innovative modular approach to large sculptures Thrift Shop Molds 10Steps to Great Bowls Stamped Impressions 4 New How-To Departments • AskAsk PMI • GettingGetting StartedStarted • BeyondBeyond BasicsBasics • SpareSpare PartsParts $5.00 US $7.50 CAN PMI Nov_Dec 04 p0IFC_13 10/27/04 9:47 AM Page IFC2 PMI Nov_Dec 04 p0IFC_13 10/27/04 9:48 AM Page 1 November/December 2004 • PotteryMaking Illustrated 1 PMI Nov_Dec 04 p0IFC_13 10/27/04 9:48 AM Page 2 TABLE OF CONTENTS Features 14Throwing a Basic Bowl by Mel Jacobson A step-by-step demonstration for creating the bowl form. 18Making Great Impressions with Stamps by Roger Graham How to make stamps for marks and decoration. 24Making Large Sculptures with Small Kilns by Norma Yuskos A modular approach to large work allows the use of a smaller kiln. 32Spray those Glazes by Kathy Chamberlin Use a spray gun for unique glaze application. 36Creating Plates and Bowls Using Glass Molds by Lou Roess Add texture and designs to your pots using old glassware. 2 PotteryMaking Illustrated • November/December 2004 PMI Nov_Dec 04 p0IFC_13 10/27/04 9:48 AM Page 3 Departments 4 Fired Up Another Exciting Moment by Tim Frederich 6 Ask PMI Studio, Kiln and Glaze Problems 8 Getting Started Hints for Even Drying by Snail Scott 10 Beyond Basics Use Your Legs by Mel Jacobson 12 Spare Parts Assemble a Throwing Gauge by Don Adamaitis 40 Off the Shelf Handbuilding Books by Sumi von Dassow 42 Kid’s Korner Nutcracker Candlestick Holders by Craig Hinshaw 48 The Peephole On the Cover: Cheryl Tall is shown with one of her modular sculp- tures in progress. -

(ALPC) Linear Pottery Cultures: Ceramics and Lithic Raw Materials Circulation

A C T AEARLY/MIDDL A R C HE NAE OLITHICE O L W EOST GER NI (LCBK) A VS C EAST A RER NP (ALA PCT)... H I C 37A VOL. XLIX, 2014 PL ISSN 0001-5229 JANUSZ K. Kozłowski, Małgorzata Kaczanowska, Agnieszka Czekaj-Zastawny, ANNA rauba-Bukowska, Krzysztof Bukowski EARLY/MIDDLE NEOLITHIC WESTERN (LBK) VS EASTERN (ALPC) LINEAR POTTERY CULTURES: CERAMICS AND LITHIC RAW MATERIALS CIRCULATION ABSTRACT J. K. Kozłowski, M. Kaczanowska, A. Czekaj-Zastawny, A. Rauba-Bukowska, K. Bukowski 2014. Early/Middle Neolithic Western (LBK) vs Eastern (ALPC) Linear Pottery Cultures: ceramics and lithic raw materials circulation, AAC 49: 37–76. In this paper we focused on the relations between the north-eastern range of the Linear Band- keramik (LBK) in the Upper Vistula basin and the area of Eastern (Alföld) Linear Pottery Culture (ALPC) in eastern Slovakia, separated by the main ridge of the Western Carpathians. Contacts between these two Early/Middle Neolithic cultural zones were manifested by the exchange of lithic raw materials (Carpathian obsidian from south-eastern Slovakia and north eastern Hun- gary vs Jurassic flint from Kraków-Częstochowa) and pottery. Ceramic exchange was studied by comparing the mineralogical-petrographic composition of the local LBK pottery from sites in the Upper Vistula basin and sherds from the same LBK sites showing ALPC stylistic features, and pottery samples from ALPC sites in eastern Slovakia. Observation under polarized light microscope and SEM-EDS analyses resulted in identification of a group of pottery samples with ALPC stylis- tic features which could be imports to LBK sites in southern Poland from Slovakia, and a group of vessels with ALPC decorations but produced in the Upper Vistula basin from local ceramic fabric, which were imitations by the local LBK population. -

Fine Chinese Works Of

AUCTION JUNE, 16TH 2018 Fine Chinese Works of Art 慵天ᷕ⚳喅埻⑩ and Buddhist Sculpturesġ ⍲ἃ㔁晽⁷ AUCTION Fine Chinese Works of Art FRONT COVER: Lot 120 – Detail A LARGE AND VERY RARE KANGXI 慵天ᷕ⚳喅埻⑩ PERIOD FAMILLE VERTE BALUSTER VASE ‘LIU HAI AND FEMALE IMMORTALS’ and Buddhist Sculptures BACK COVER: Lot 77 ⍲ἃ㔁晽⁷ A LARGE YUAN / MING DYNASTY PAINTING OF FEMALE DEITIES WITH th pm GESSO HIGHLIGHTS Saturday, June 16 2018 at 2 CET CATALOG CA0618 VIEWING www.zacke.at IN OUR GALLERY June 11th - June 16th Monday - Friday 10am - 6pm Saturday - June 16th 10am - 1pm and by appointment GALERIE ZACKE MARIAHILFERSTRASSE 112 Lot 98 A LARGE AND IMPORTANT MING 1070 VIENNA AUSTRIA DYNASTY POLYCHROME-LACQUERED WOOD FIGURE OF GUANYIN Tel +43 1 532 04 52 Fax +20 E-mail offi[email protected] 1 IMPORTANT INFORMATION ABSENTEE BIDDING FORM (According to the general terms and conditions of business Gallery Zacke Vienna) FOR THE AUCTION FINE CHINESE WORKS OF ART AND BUDDHIST SCULPTURES CATALOG CA0618 ON DATE Saturday, June 16th 2018 at 2pm CET NO. TITLE BID IN EURO Endangered Species / CITES Information Some items in this catalogue may consist of material such as for example ivory, rhinoceros horn, tortoise shell, coral or any rare types of tropical wood, and are therefore subject to the Convention on International Trade in Endangered Species of Wild Fauna and Flora [CITES]. Such items may only be exported outside the European Union after an export permit in accordance with CITES has been granted by the Austrian authorities. Zacke Gallery cannot and does not guarantee that such export permit may or will be obtained, but will by order of the winning bidder, once and exclusively after the item in question has been paid in full, apply to obtain such a permit at a fixed administrative fee of euro 500, - per application.