978-613-9-81951-5

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Initial Environmental Examination IND: Second Rural Connectivity Investment Program

Initial Environmental Examination June 2018 IND: Second Rural Connectivity Investment Program- Tranche 2 Madhya Pradesh Prepared by National Rural Road Development Agency, Ministry of Rural Development, Government of India for the Asian Development Bank. CURRENCY EQUIVALENTS (as of 8 June 2018) Currency unit – Indian Rupees (INR/Rs) INR1.00 = $ 0.014835 $1.00 = INR 67.41 ABBREVIATIONS ADB : Asian Development Bank BIS : Bureau of Indian Standards CD : Cross Drainage MPRRDA Madhya Pradesh Rural Road Development Authority CGWB : Central Ground Water Board CO : carbon monoxide COI : Corridor of Impact DM : District Magistrate EA : Executing Agency EAF : Environment Assessment Framework ECOP : Environmental Codes of Practice EIA : Environmental Impact Assessment EMAP : Environmental Management Action Plan EO : Environmental Officer FEO : Field Environmental Officer FGD : Focus Group Discussion FFA : Framework Financing Agreement GOI : Government of India GP : Gram panchyat GSB : Granular Sub Base HA : Hectare HC : Hydro Carbon IA : Implementing Agency IEE : Initial Environmental Examination IRC : Indian Road Congress LPG : Liquefied Petroleum Gas MFF : Multitranche Financing Facility MORD : Ministry of Rural Development MORTH : Ministry of Road Transport and Highways MOU : Memorandum of Understanding MPRRDA : Madhya Pradesh Rural Road Development Agency NAAQS : National Ambient Air Quality Standards NGO : Non-governmental Organisation NOx : nitrogen oxide NC : Not Connected NGO : Non-government Organization NRRDA : National Rural Road Development -

NATIONAL WEEKLY (24 - 31 October) BASIC EXCHANGE and COOPERATION AGREEMENT (BECA) 1

Build your own success story! NATIONAL WEEKLY (24 - 31 October) BASIC EXCHANGE AND COOPERATION AGREEMENT (BECA) 1. India and the United States signed the Basic Exchange and Cooperation Agreement (BECA). 2. BECA, along with the two agreements signed earlier — the Logistics Exchange Memorandum of Agreement (LEMOA) and the Communications Compatibility and Security Agreement (COMCASA) — completes a troika of ―foundational pacts‖ for deep military cooperation between the two countries. 3. BECA will help India get real-time access to American geospatial intelligence that will enhance the accuracy of automated systems and weapons like missiles and armed drones. DR. TULSI DAS CHUGH AWARD 1. CSIR-CDRI Scientist, Dr Satish Mishra bags "Dr. Tulsi Das Chugh Award-2020" given by National Academy of Medical Sciences (India) in recognition of his research work on Malaria parasite's life cycle. UNITED AGAINST CORONA- EXPRESS THROUGH ART 1. A six year old Bangladeshi boy Anzar Mustaeen Ali won a special prize of USD 1000 for his artwork in the global art competition organised by the Indian Council of Cultural Relations (ICCR). FENI BRIDGE 1. The bridge is being built over the Feni River and will connect Tripura with Chittagong port of Bangladesh. Plot No. 43, S-1 & S-3, 2nd Floor, R.R. Arcade, (Behind G K Palace), Zone-II, M.P. Nagar, BHOPAL Mob.: 7223901339 Build your own success story! INDIA-US 2+2 MINISTERIAL DIALOGUE 1. External Affairs Minister S Jaishankar and Defence Minister Rajnath Singh held the third edition of the 2+2 talks with US Secretary of State Mike Pompeo and Secretary of Defense Mark Esper. -

National Parks in India (August)

NATIONAL PARKS IN INDIA (AUGUST) List of National Parks in India States Andhra Pradesh (3) ✓ Papikonda National Park ✓ Rajiv Gandhi (Rameshwaram) National Park ✓ Sri Venkateswara National Park Arunachal Pradesh (2) ✓ Mouling National Park ✓ Namdapha National Park Assam (7) ✓ Rajiv Gandhi (Orang) National Park ✓ Kaziranga National Park ✓ Nemeri National Park ✓ Manas National Park ✓ Dibru-Saikhowa National Park ✓ Raimona National Park (2021) ✓ Dehing-Patkai National Park (2021) Bihar (1) ✓ Valmiki National Park Chhattisgarh (3) ✓ Kanger Valley National Park ✓ Indravati (Kutru) National Park ✓ Guru Ghasidas National Park Goa (1) ✓ Mollem National Park Gujarat (4) ✓ Vansda National Park ✓ Gir National Park ✓ Marine (Gulf of Kachchh) National Park ✓ Bluckbuck (Velavadar) National Park F o l l o w u s : YouTube, Website, Telegram, Instagram, Facebook. Page | 1 NATIONAL PARKS IN INDIA (AUGUST) Haryana (2) ✓ Sultanpur National Park ✓ Kalesar National Park Himachal Pradesh (5) ✓ Pin Valley National Park ✓ Inderkilla National Park ✓ Simbalbara National Park ✓ Khirganga National Park ✓ Great Himalayan National Park Jharkhand (1) ✓ Betla National Park Karnataka (5) ✓ Anshi National Park ✓ Bandipur National Park ✓ Bannerghatta National Park ✓ Kudremukh National Park ✓ Nagarahole (Rajiv Gandhi) National Park Kerala (6) ✓ Silent Valley National Park ✓ Pambadum National Park ✓ Periyar National Park ✓ Mathikettan National Park ✓ Eravikulam National Park ✓ Anamudi Shola National Park Madhya Pradesh (11) ✓ Bandhavgarh National Park ✓ Dinosaur National Park -

List of National Parks and Wildlife Sanctuaries in India

List of National Parks and Wildlife Sanctuaries in India Sr.no. National Park Famous State 1. Sariska National Park For tigers Rajasthan 2. Mount Abu Wild Life For rare flora with rare hyena Rajasthan Sanctuary and jackal 3. Kevala Devi National For parties of the extinct and Rajasthan Park scarce caste 4. Pass National Park For crocodiles with thin Rajasthan mouths 5. Kumbhalgarh Nilgai, sambar bear, wild boar Rajasthan Sanctuary 6. Dazzat National Park Kshis great for indian bustard Rajasthan 7. Taal Chhapar Sanctuary For blackbucks and exotic Rajasthan birds visiting here 8. Ranthambhore National For Bengal tiger Rajasthan Park 9. Kuno National Park For asian lions Madhya Pradesh 10. Panna National Park Famous for wild cat, deer, Madhya vulture, tiger Pradesh 11. Mandla Plant Fausil For plant fossils Madhya National Park Pradesh 12. Madhav National Park For sambar, hyena, tiger, Madhya nilgai, gentle bear, crocodile, Pradesh chinkara, deer, antelope, leopard etc. 13. Bandhavgarh National For Bengal tiger Madhya Park Pradesh 14. Van Vihar Park For major Bengal tigers and Madhya other creatures Pradesh WWW.NAUKRIASPIRANT.COM 1 15. Sanjay National Park For Bengal tiger Madhya Pradesh 16. Kanha National Pak Famous for tigers) Madhya Pradesh 17. Satpura National Park For tiger, blackbuck and Madhya reindeer Pradesh 18. Pench National Park For Royal Bengal Tiger, Madhya Leopard, Sloth Bear, Chinkara Pradesh 19. Chandraprabha For chital, krishnamag, bear, Uttar National Park nilgai Pradesh 20. Dudwa National Park Reindeer for tigers Uttar Pradesh 21. Namdapha National For pedo umbrella Arunachal Park Pradesh 22. Sultanpur National Park Siberian cranes, for waterfowl Haryana 23. -

Assessment of Minimum Water Flow Requirements of Chambal River

Assessment of minimum water flow requirements of Chambal River in the context of Gharial (Gavialis gangeticus) and Gangetic Dolphin (Platanista gangetica) conservation Study Report April 2011 Assessmentofminimumwaterflowrequirements ofChambalRiverinthecontextofGharial(Gavialis gangeticus)andGangeticDolphin(Platanista gangetica)conservation StudyReport April2011 Contributors:SyedAinulHussain,R.K.Shrama,NiladriDasguptaandAngshumanRaha. CONTENTS Executivesummary 1 1. Background 3 2. Introduction 3 3. TheChambalriver 3 4. Existingandproposedwaterrelatedprojects 5 5. TheNationalChambalSanctuary 8 6. Thegharial(Gavialisgangeticus) 8 7. TheGangeticdolphin(Platanistagangetica) 9 8. Objectivesofassessment 10 9. Methodsofassessment 12 10. Results 13 11. Discussion 20 12. References 22 13. AppendixI–IV 26 AssessmentofminimumwaterflowrequirementsofChambalRiver ʹͲͳͳ EXECUTIVESUMMARY The Chambal River originates from the summit of Janapav hill of the Vindhyan range at an altitudeof854mabovethemslat22027’Nand75037’EinMhow,districtIndore,Madhya Pradesh.Theriverhasacourseof965kmuptoitsconfluencewiththeYamunaRiverinthe EtawahdistrictofUttarPradesh.ItisoneofthelastremnantriversinthegreaterGangesRiver system, which has retained significant conservation values. It harbours the largest gharial population of the world and high density of the Gangetic dolphin per river km. Apart from these,themajorfaunaoftheRiverincludesthemuggercrocodile,smoothͲcoatedotter,seven speciesoffreshwaterturtles,and78speciesofwetlandbirds.Themajorterrestrialfaunaofthe -

Ranthambore Tiger Sanctuary: Rajasthan

Ranthambore Tiger Sanctuary: Rajasthan drishtiias.com/printpdf/ranthambore-tiger-sanctuary-rajasthan Why in News Six tigers are missing in Ranthambore Tiger Sanctuary (Rajasthan). Key Points About: Ranthambore Tiger Reserve lies in the eastern part of Rajasthan state in Karauli and Sawai Madhopur districts, at the junction of the Aravali and Vindhya hill ranges. It comprises the Ranthambore National Park as well as Sawai Mansingh and Kailadevi Sanctuaries. The Ranthambore fort, from which the forests derive their name, is said to have a rich history of over 1000 years. It is strategically located atop a 700 feet tall hill within the park and is believed to have been built in 944 AD by a Chauhan ruler. This isolated area with tigers in it represents the north-western limit of the Bengal tiger’s distribution range and is an outstanding example of Project Tiger’s efforts for conservation in the country. India has 2,967 tigers, a third more than in 2014, according to results of a census made public in July 2020. Ranthambore, according to this exercise, had 55 tigers. Features: The reserve consists of highly fragmented forest patches, ravines, river streams and agricultural land. It is connected to Kuno-Palpur Landscape in Madhya Pradesh, through parts of Kailadevi Wildlife Sanctuary, the ravine habitats of Chambal and the forest patches of Sheopur. Tributaries of River Chambal provide easy passage for tigers to move towards the Kuno National Park. 1/2 Vegetation and Wildlife: The vegetation includes grasslands on plateaus and dense forests along the seasonal streams. The forest type is mainly tropical dry deciduous with ‘dhak’ (Butea monosperma), a species of tree capable of withstanding long periods of drought, being the commonest. -

Protected Species and National Parks Operation Clean Art

Protected Species and National Parks Operation Clean Art • Operation Clean Art, conceived by Wildlife Crime Control Bureau (WCCB), is the first pan India operation to crack down on the smuggling of mongoose hair in the country. Great Indian Bustard Desert National Park Sanctuary — Rajasthan Rollapadu Wildlife Sanctuary – Andhra Pradesh Karera Wildlife Sanctuary– Madhya Pradesh With reference to the Great Indian Bustard, which of the following statements is/are correct? 1. It has been classified as critically Endangered species as per the IUCN’s Red List. 2. It is endemic to India only. 3. To protect this species, Project Great Indian Bustard was launched by the Ministry of Environment. 4. In India, the great Indian Bustards are found only in Rollapadu wildlife sanctuary. Select the correct answer using the code given below: a. 1 only b. 1, 3 and 4 only c. 1 and 2 only d. 3 and 4 only Snow Leopard Snow leopard states/UTs are: • Ladakh • Jammu & Kashmir • Himachal Pradesh • Uttarakhand • Sikkim • Arunachal Pradesh Globba andersonii The plant, known commonly as ‘dancing ladies’ or ‘swan flowers’ was thought to have been extinct until its “recollection”, for the first time since 1875 has been sighted in the Sikkim Himalayas near the Teesta river valley region after a gap of nearly 136 years. Pongamia pinnata, which is a leguminous tree, has been in the news recently for which of the following reasons? a. Its seeds are used to formulate vaccines for malaria. b. Being a potential source for the production of Biodiesel. c. For producing protein rich cereals with potential to fight hidden malnutrition. -

MADHYA PRADESH” in “ENGLISH MEDIUM”

MPPSC PRELIMS The Only Comprehensive “CURRENT AFFAIRS” Magazine of “MADHYA PRADESH” in “ENGLISH MEDIUM” National International MADHYA CURRENT Economy PRADESH MP Budget Current Affairs AFFAIRS MP Eco Survey MONTHLY Books-Authors Science Tech Personalities & Environment Sports JANUARY 2020 Contact us: mppscadda.com [email protected] Call - 8368182233 WhatsApp - 7982862964 Telegram - t.me/mppscadda JANUARY 2020 (CURRENT AFFAIRS) 1 MADHYA PRADESH NEWS State's first day care launched Location: Vivekananda Park, Kotra (bhopal) Objective: To provide library for the elderly, TV set for entertainment, chess, and facilities. Fourth Water Festival organized Festival Date : 3rd January to 3rd February 2020 Festival Place : Hanuwantia (Indira Sagar Dam), District Khandwa Indira Sagar Dam is the second largest man made reservoir in Asia. First Water Festival: Year 2016 Meeting between Spiritual Minister of Madhya Pradesh and Foreign Minister of Sri Lanka Meeting place: Colombo, Sri Lanka Major decisions Direct airline to be started between Bhopal Colombo The World Buddhist Museum and Institute of Education will be established in Sanchi. Spiritual Minister of Madhya Pradesh, Mr. BPC Sharma. Sri Lankan Foreign Minister : Mr. Dinesh Govardhan Khadi Festival 2020 Khadi Festival 2020 was launched at Gauhar Mahal Bhopal. Minister of Cottage and Village Industries : Mr. Harsh Yadav. Khadi Board started Khadi Gram Udyog Vikaas Kendra in Chhindwara in PPP mode. Khandwa is going to start center in Hoshangabad , Guna , Satna , Shahdol and Sagar Khadi garments will now be sold under the brand name “Kabira” in the state Khadi has also been exempted from GST. Launch of country's first e - Waste clinic. Inauguration date and location : 23 January MP Nagar Zone 1 Bhopal Bhopal was selected as a pilot project by the Central Pollution Control Board. -

Printpdf/Madhya-Pradesh-Public-Service-Commission-Mppcs-Gk-State-Pcs-English

Drishti IAS Coaching in Delhi, Online IAS Test Series & Study Material drishtiias.com/printpdf/madhya-pradesh-public-service-commission-mppcs-gk-state-pcs-english Madhya Pradesh Public Service Commission (MPPCS) GK Madhya Pradesh GK Formation 1st november, 1956 Capital Bhopal Population 7,26,26,809 Region 3,08,252 sq. km. Population density in state 236 persons per sq.km. Total Districts 52 (52nd District – Niwari) Other Name of State Hriday Pradesh, Soya State, Tiger State, Leopard State High Court Jabalpur (Bench – Indore, Gwalior) 1/16 State Symbol State Animal: State Flower: Barahsingha (reindeer) White Lily State Bird: State Dance: Dudhraj (Shah Bulbul) Rai 2/16 State Tree: Banyan Official Game: Malkhamb Madhya Pradesh : General Information State – Madhya Pradesh Constitution – 01 November, 1956 (Present Form – 1 November 2000) Area – 3,08,252 sq. km. Population – 7,26,26,809 Capital – Bhopal Total District – 52 No. of Divisions – 10 Block – 313 Tehsil (January 2019) – 424 The largest tehsil (area) of the state – Indore The smallest tehsil (area) of the state – Ajaygarh (Panna) Town/city – 476 Municipal Corporation (2018-19) – 16 Municipality – 98 City Council – 294 Municipality – 98 (As per Government Diary 2021: 99) Total Village – 54903 Zilla Panchayat – 51 Gram Panchayat – 22812 (2019–20) Tribal Development Block – 89 State Symbol – A circle inside the 24 stupa shape, in which there are earrings of wheat and paddy. State River – Narmada State Theater – Mach Official Anthem – Mera Madhya Pradesh Hai (Composer – Mahesh Srivastava) -

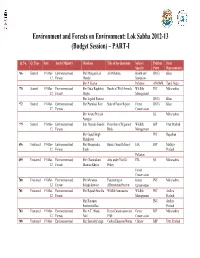

Environment and Forests on Environment: Lok Sabha 2012-13 (Budget Session) – PART-I

Environment and Forests on Environment: Lok Sabha 2012-13 (Budget Session) – PART-I Q. No. Q. Type Date Ans by Ministry Members Title of the Questions Subject Political State Specific Party Representative *66 Starred 19-Mar- Environment and Shri Mangani Lal Air Pollution Health and JD(U) Bihar 12 Forests Mandal Sanitation Shri P. Kumar Pollution AIADMK Tamil Nadu *70 Starred 19-Mar- Environment and Shri Datta Raghobaji Deaths of Wild Animals Wildlife INC Maharashtra 12 Forests Meghe Management Shri Jagdish Sharma JD(U) Bihar *72 Starred 19-Mar- Environment and Shri Purnmasi Ram State of Forest Report Forest JD(U) Bihar 12 Forests Conservation Shri Anand Prakash SS Maharashtra Paranjpe *79 Starred 19-Mar- Environment and Smt. Maneka Gandhi Protection of Migratory Wildlife BJP Uttar Pradesh 12 Forests Birds Management Shri Gopal Singh INC Rajasthan Shekhawat 696 Unstarred 19-Mar- Environment and Shri Bhoopendra Bharat Oman Refinery EIA BJP Madhya 12 Forests Singh Pradesh Pollution 699 Unstarred 19-Mar- Environment and Shri Chandrakant Area under 'No-Go' EIA SS Maharashtra 12 Forests Bhaurao Khaire Policy Forest Conservation 700 Unstarred 19-Mar- Environment and Shri Marotrao Functioning of Forest INC Maharashtra 12 Forests Sainuji Kowase Afforestation Projects Conservation 701 Unstarred 19-Mar- Environment and Shri Rajaiah Siricilla Wildlife Sanctuaries Wildlife INC Andhra 12 Forests Management Pradesh Shri Rayapati INC Andhra Sambasiva Rao Pradesh 703 Unstarred 19-Mar- Environment and Shri A.T. (Nana) Forest Conservation Act, Forest BJP Maharashtra 12 Forests Patil 1980 Conservation 708 Unstarred 19-Mar- Environment and Shri Surendra Singh Carbon Emission Norms Climate BSP Uttar Pradesh 12 Forests Nagar Change and Meteorology 711 Unstarred 19-Mar- Environment and Shri Jeetendra Singh Rehabilitation of Asiatic Wildlife BJP Madhya 12 Forests Bundela Lions Management Pradesh Shri Narendra Singh BJP Madhya Tomar Pradesh 713 Unstarred 19-Mar- Environment and Smt. -

Prey Base Analysis in Kuno National Park, Sheopur, Madhya Pradesh

International Journal of Science and Research (IJSR) ISSN: 2319-7064 ResearchGate Impact Factor (2018): 0.28 | SJIF (2019): 7.583 Prey Base Analysis in Kuno National Park, Sheopur, Madhya Pradesh Vikas Kumar Soni Department of Geography, Govt. P.G. Collage, Sheopur, Madhya Pradesh, India Abstract: Kuno National Park is spread over an area of 748.7618 km2 and is situated in Sheopur district of Madhya Pradesh. The National Park is part of the Kuno National Park division which covers an area of 1235.39 km2. Kuno River, one of the major tributaries of Chambal River flows through the entire length bisecting the National Park division. The division comprises of eight ranges, with Palpur west and Palpur east ranges forming the Sanctuary. The six ranges in the buffer area are Moravan east and west, Sironi north and south, Agara west and east The area is classified as Semi-arid zone (4b), Gujarat- Rajputana bio-geographic region (Rodgers et al. 2002). Keywords: Tributaries, Flows, Bisecting, Bio-geographic, Reserve 1. Introduction to over hunting and habitat destruction. Kuno is currently home to tiger, Indian wolf, jackal, leopard, langur monkey, Kuno park is legendary for tigers, Jackal, Chinkara and now blue-bull, chinkara and spotted deer[10]. this park getting to become unique because Asiatic lions can now be relocated from Gir to the Kuno park . There are large Wildlife: The herbivores found in this area are Axis axis scale deaths within the population annually as a result (Chital), Rusa unicolor (Sambar), Boselaphus tragocamelus of ever increasing competition due to animal (Nilgai), Sus scrofa (Wild pig), Gazella bennetii (Chinkara), overcrowding. -

Complete List of National Parks & Wildlife Sanctuaries in India

Complete list of National Parks & Wildlife Sanctuaries in India About National Parks in India What is a National Park? An area that is identified as being rich in biodiversity is strictly protected from activities like industry or residential development, poaching, deforestation, hunting, forestry, grazing, cultivation, and any other activity which may damage the flora and fauna of that region. The area is declared as a National Park under law, and the boundaries are well defined. They are not to be exploited in any manner whatsoever. Which Indian law provides provision for National Parks? The Wildlife Protection Act of 1972 provides provision for several protected areas and reserves including National Parks, Wildlife Sanctuaries, Tiger Reserves, Conservation Reserves, and Community Reserves. National Parks and Tiger Reserves are more strictly protected than other areas. How many National Parks are there in India? There are a total of 103 National Parks in India (as of 2017). Which is the state with the maximum number of National Parks, and Maximum area under National Parks? Madhya Pradesh and Andaman and Nicobar have the highest number of National Parks (9 each). Largest and Smallest National Park in India? Largest – Hemis National Park, Jammu & Kashmir Smallest – South Button Island National Park, Andaman, and the Nicobar Islands Important facts about the National Parks in India Number of National 104 Total area covered 40,501 sq.km. Maximum National Park M.P. (9), Andaman & Nicobar state (9) First National Park Jim Corbett National Park Largest National Park Hemis National Park Smallest National Park South Button National Park Latest National Park Kuno National Park What is the difference between National Parks and Wildlife Sanctuaries? The difference between a National Park and a Wildlife Sanctuary is that no human activity is allowed inside a national park, while limited activities are permitted within the sanctuary.