Nature Essentials Surround - Data Sheet Nature Essentials

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Louisiana Waterthrush (Parkesia Motacilla) Christopher N

Louisiana Waterthrush (Parkesia motacilla) Christopher N. Hull Keweenaw Co., MI 4/6/2008 © Mike Shupe (Click to view a comparison of Atlas I to II) This fascinating southern waterthrush sings its loud, clear, distinctive song over the sound of The species is considered area-sensitive babbling brooks as far north as eastern (Cutright 2006), and large, continuous tracts of Nebraska, lower Michigan, southern Ontario, mature forest, tens to hundreds of acres in size, and New England, and as far south as eastern are required (Eaton 1958, Eaton 1988, Peterjohn Texas, central Louisiana, and northern Florida. and Rice 1991, Robinson 1995, Kleen 2004, It winters from Mexico and southern Florida Cutright 2006, McCracken 2007, Rosenberg south to Central America, northern South 2008). Territories are linear, following America, and the West Indies. (AOU 1983, continuously-forested stream habitat, and range Robinson 1995). 188-1,200 m in length (Eaton 1958, Craig 1981, Robinson 1990, Robinson 1995). Hubbard (1971) suggested that the Louisiana Waterthrush evolved while isolated in the Distribution southern Appalachians during an interglacial Using the newer findings above, which were period of the Pleistocene. It prefers lotic derived using modern knowledge and (flowing-water) upland deciduous forest techniques, the "logical imperative" approach of habitats, for which it exhibits a degree of Brewer (1991) would lead us to predict that the morphological and behavioral specialization Louisiana would have been historically (Barrows 1912, Bent 1953, Craig 1984, Craig distributed throughout the SLP to the tension 1985, Craig 1987). Specifically, the Louisiana zone, and likely beyond somewhat, in suitable Waterthrush avoids moderate and large streams, habitat. -

Northern and Louisiana Waterthrushes in California

CALIFORNIA BIRDS Volume 2, Number 3, 1971 NORTHERN AND LOUISIANA WATERTHRUSHES IN CALIFORNIA Laurence C. Binford INTRODUCTION No thorough summaryof the Californiastatus of the Northern Waterthrush Seiurus noveboracensis and the Louisiana Waterthrush S. rnotacillahas been publishedsince 1944 (Grinnelland Miller). Since then the statusof the LouisianaWaterthrush has not changed,there still beingonly one recordfor the state. For the Northern Waterthrush, on the other hand, the increasein number and sophisticationof birdershas producedmany additional records, from which certain trends begin to emerge. One problem that rendersthese new data difficult to interpret is "observerbias." Field ornithologiststend to be selectivein their birding habits in respectto localitiesand dates. As a result, large areas of the state remain virtually unworked, and other localities are visited only at certain times of the year. My remarksconcerning the statusof the Northern Waterthrushin Californiaare thereforelargely speculative. Calif. Birds2:77-92, 1971 77 WATERTHRUSHES IN CALIFORNIA NORTHERN WATERTHRUSH The Northern Waterthrush breeds from north-central Alaska and the tree line in northern Canada south to central British Columbia and the northern tier of states from Idaho eastward. In winter it occursprimarily from southernMexico, the Bahamas,and Bermuda south through Central America and the West Indies to northern South America. It winters in smaller numbers on both coasts of Mexico north to San Luis Potosi,Sinaloa (rare), Nayarit (common), and southern Baja California, and casuallyin southeasternUnited States(Alden, 1969; AmericanOrnithologists' Union, 1957; Miller, et al., 1957). Althoughthis speciesmigrates principally through central and eastern United States and acrossthe Gulf of Mexico, it is known to be a regular but rather uncommon transient through eastern Arizona(Phillips, et al., 1964). -

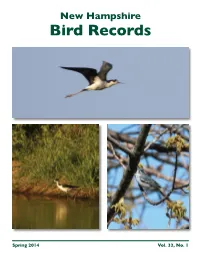

NH Bird Records

New Hampshire Bird Records Spring 2014 Vol. 33, No. 1 IN CELEBRATION his issue of New Hampshire Bird Records with Tits color cover is sponsored by a friend in celebration of the Concord Bird and Wildlife Club’s more than 100 years of birding and blooming. NEW HAMPSHIRE BIRD RECORDS In This Issue VOLUME 33, NUMBER 1 SPRING 2014 From the Editor .......................................................................................................................1 Photo Quiz ..........................................................................................................................1 MANAGING EDITOR 2014 Goodhue-Elkins Award – Allan Keith and Robert Fox .....................................................2 Rebecca Suomala Spring Season: March 1 through May 31, 2014 .......................................................................3 603-224-9909 X309, [email protected] by Eric Masterson The Inland White-winged Scoter Flight of May 2014 ..............................................................27 TEXT EDITOR by Robert A. Quinn Dan Hubbard Beyond the Sandhill Crane: Birding Hidden Towns of Northwestern Grafton County ............30 SEASON EDITORS by Sandy and Mark Turner, with Phil Brown Eric Masterson, Spring Backyard Birder – Waggle Dance of the Woodpeckers .............................................................32 Tony Vazzano, Summer by Brenda Sens Lauren Kras/Ben Griffith, Fall Field Notes ........................................................................................................................33 -

Wood Warblers Wildlife Note

hooded warbler 47. Wood Warblers Like jewels strewn through the woods, Pennsylvania’s native warblers appear in early spring, the males arrayed in gleaming colors. Twenty-seven warbler species breed commonly in Pennsylvania, another four are rare breeders, and seven migrate through Penn’s Woods headed for breeding grounds farther north. In central Pennsylvania, the first species begin arriving in late March and early April. Louisiana waterthrush (Parkesia motacilla) and black and white warbler (Mniotilta varia) are among the earliest. The great mass of warblers passes through around mid-May, and then the migration trickles off until it ends in late May by which time the trees have leafed out, making it tough to spot canopy-dwelling species. In southern Pennsylvania, look for the migration to begin and end a few days to a week earlier; in northern Pennsylvania, it is somewhat later. As summer progresses and males stop singing on territory, warblers appear less often, making the onset of fall migration difficult to detect. Some species begin moving south as early as mid and late July. In August the majority specific habitat types and show a preference for specific of warblers start moving south again, with migration characteristics within a breeding habitat. They forage from peaking in September and ending in October, although ground level to the treetops and eat mainly small insects stragglers may still come through into November. But by and insect larvae plus a few fruits; some warblers take now most species have molted into cryptic shades of olive flower nectar. When several species inhabit the same area, and brown: the “confusing fall warblers” of field guides. -

Schodack Birding Checklist

Species Sp Su F W Species Sp Su F W SHRIKES & VIREOS WOOD-WARBLERS (cont.) Northern Shrike R Black-throated Blue Warbler C C BIRDS Yellow-throated Vireo C C Black-throated Green Warbler C C Red-eyed Vireo C C Blackburnian Warbler U U OF Warbling Vireo C C Prothonotary Warbler U U Blue-headed Vireo C C Black-and-white Warbler C C JAYS & CROWS Mourning Warbler U U SCHODACK ISLAND Blue Jay A A A A Cerulean Warbler*# U U American Crow* A A A A Canada Warbler U U STATE PARK Fish Crow O O O American Redstart* C C 1 Schodack Landing Way SWALLOWS Common Yellowthroat C C Schodack Landing, NY 12156 Purple Martin U C Pine Warbler U U (518) 732-0187 Tree Swallow* U C Prairie Warbler U C Barn Swallow* U C Blackpoll Warbler U U Bank Swallow* U C Hooded Warbler U C CHICKADEES, TITMICE & NUTHATCHES Yellow-throated Warbler O O Black-capped Chickadee A A A A SPARROWS Tufted Titmouse C C C C Eastern Towhee C C White-breasted Nuthatch C C C C Field Sparrow C C CREEPERS, WRENS & KINGLETS Song Sparrow* C A C C Brown Creeper U U U U Swamp Sparrow C C House Wren* U C American Tree Sparrow C C C C Carolina Wren C C C C Chipping Sparrow* C C Marsh Wren U C U Savannah Sparrow C C Ruby-crowned Kinglet U U White-throated Sparrow C U U U Golden-crowned Kinglet U U White-crowned Sparrow U U Blue-gray Gnatcacther C Dark-eyed Junco C C C C Cerulean Warbler THRUSHES, MIMICS, STARLINGS & WAXWINGS CARDINALS American Robin* A C C O Northern Cardinal* A A A A Located on a peninsula in the northern region of Eastern Bluebird* A A C O Scarlet Tanager U C the Hudson River Estuary system, Schodack Island Veery* A C U Rose-breasted Grosbeak* U C State Park’s 864-acre Bird Conservation Area is Wood Thrush* A C U Indigo Bunting U C critical breeding habitat for many species, including Hermit Thrush C C U ORIOLES & BLACKBIRDS species of special concern such as Cerulean Warblers. -

FRONTISPIECE. Three-Striped Warblers (Basileuterus Tristriatus) Were Studied in the Northern Andes of Venezuela. Temperate and T

FRONTISPIECE. Three-striped Warblers (Basileuterus tristriatus) were studied in the northern Andes of Venezuela. Temperate and tropical parulids differ strongly in life histories. Three-striped Warblers have smaller clutches, longer incubation periods, lower nest attentiveness, longer off-bouts, and slower nestling growth rates than most temperate species. Water color by Don Radovich. Published by the Wilson Ornithological Society VOL. 121, NO. 4 December 2009 PAGES 667–914 The Wilson Journal of Ornithology 121(4):667–678, 2009 BREEDING BIOLOGY OF THE THREE-STRIPED WARBLER IN VENEZUELA: A CONTRAST BETWEEN TROPICAL AND TEMPERATE PARULIDS W. ANDREW COX1,3 AND THOMAS E. MARTIN2 ABSTRACT.—We document reproductive life history traits of the Three-striped Warbler (Basileuterus tristriatus) from 146 nests in Venezuela and compare our results to data from the literature for other tropical and temperate parulid species. Mean (6 SE) clutch size was 1.96 6 0.03 eggs (n 5 96) and fresh egg mass was 2.09 6 0.02 g. The incubation period was 15.8 6 0.2 days (n 5 23) and the nestling period was 10.5 6 0.3 days (n 5 12). Males did not incubate and rarely provided food for females during incubation. Females had 57 6 2% (n 5 49) nest attentiveness (% of time on the nest incubating), which caused egg temperature to commonly become cold relative to development. Both adults fed nestlings and feeding rates increased with nestling age. The growth rate constant for nestlings based on mass was K 5 0.490, which is slower than for north temperate warblers. -

Wildlife Report

Crescent Creek Wild and Scenic River Crescent Ranger District Deschutes National Forest Wildlife Report Includes: Executive Summary 1. Wildlife Habitats 3.Managementrnoi3,".Jlf 3#,iil:l:*enservationconcern, and Landbird Conservation Strategy Focal Species 4. Survey and Manage Prepared Joan L Wildlife Biologist 9 - Updated maps and acres for new boundary. Updated TES with the 2019 TES Species list. Box\CRE-eaCrescentCreekWSR20l T\Specialist Reports\FinalWildlifeReport\FinalWLReport26June20l g Box\Wildlife-2600-CRE\2620_fwlllanning\wl_reports\CrescentCreekWSJune20l8\FinalWildlifeReport\FinalWLReport26June20l g 7 EXECUTIVE SUMMARY lntroduction An analysis of wildlife habitats was performed for the proposed Crescent Creek Wild and Scenic River Corridor Boundary (WSR) and Management Plan on the Crescent Ranger District of the Deschutes National Forest. The potential effects finalizing the designation of the WSR Boundary andproposed Management Plan on viable populations or habitat of Proposed, Threatened, Endangered and Region 6 Forester's Sensitive wildlife species (TES), Management Indicator Species (MIS), Birds of Conservation Concem (BCC), Landbird Conservation Strategy Focal Species (LBFS), and Northwest Forest Plan Survey and Manage (SM), were evaluated. Designation of a final Wild and Scenic River Conidor Boundary changes some Forest Plan Allocations potentially altering the consideration for wildlife species and habitat. The Management Plan is a management direction document addressing the allocation changes and future management of the lands within the WSR Corridor. The plan itself does not involve any on-the-ground management activities that could cause effects to wildlife species. Any future proposed projects under the management plan would need site-specific analyses and documentation of effects to these species. The following is a sunmary of the analysis. -

Global Perspectives on Neotropical Migratory Bird Conservation in the Northeast: Long-Term Responsibility Versus Immediate Concern

Global Perspectives on Neotropical Migratory Bird Conservation in the Northeast: Long-Term Responsibility Versus Immediate Concern Kenneth V. Rosenberg Jeffrey V. Wells Abstract—We assessed the conservation priorities of Neotropical welfare. Responsibility for important populations leads to long- migratory bird species in the Northeast Region (USFWS Region 5) term conservation planning, especially in the most important geo- using the most up-to-date information available on distribution, graphic areas, whereas concern for declining populations leads to abundance, and population trends. Priority rankings were devel- immediate conservation action, especially in “hot-spot” areas. oped using the percent of the total population in the Northeast as a measure of the importance of the region to each species’ long-term persistence. We identified 34 species with at least 15% of their total Setting regional conservation priorities is an important population in Region 5. Species for which the Northeast Region is step in the Partners in Flight (PIF) planning process. At the particularly important include Bicknell’s Thrush, Scarlet Tanager, regional level, prioritization may represent a conflict be- Worm-eating Warbler, Louisiana Waterthrush, and Wood Thrush. tween global needs of the entire population of a species and The importance of adjoining USFWS Regions, states and Canadian local concerns or pressures. The PIF species prioritization provinces, and physiographic areas to each species was established scheme (Carter and others, this proceedings) provides an using the same measure. Eastern Canada and the Southeast Region objective means for assessing the relative conservation con- are particularly important to consider as partners in any regional cern for bird species throughout the United States. -

New Hampshire Wildlife and Habitats at Risk

CHAPTER TWO New Hampshire Wildlife and Habitats at Risk Abstract All wildlife species native to New Hampshire were eligible for identification as Species of Greatest Conservation Need (SGCN), including game species, non-game species, fish and marine animals. A number of species prioritization lists and expert review processes were used to determine which species should be included as SGCN. A total of 169 species are identified as SGCN in the 2015 Wildlife Action Plan, of which 27 species are listed as state endangered and 14 listed as state threatened. In the 2005 Wildlife Action Plan 118 species were listed as SGCN, and all but 13 of the 2005 SGCN are included in the 2015 revision. The Wildlife Action Plan also identifies 27 distinct habitats that support both common species and species of greatest conservation need. By identifying and protecting high quality examples of all of New Hampshire’s natural communities, all of the state’s native wildlife species will have access to intact habitats. Overview New Hampshire is home to over 500 vertebrate species and thousands of invertebrates. Many of these are common species that thrive in the state’s diverse landscapes and provide enjoyment through wildlife observation, hunting, fishing, and trapping. This chapter describes the process of determining which species are in trouble – declining in numbers, squeezed into smaller patches of habitat, and threatened by a host of issues. These species are designated as Species of Greatest Conservation Need (SGCN). They include not only species on the NH Endangered Species list, but also those that are not yet seriously threatened. -

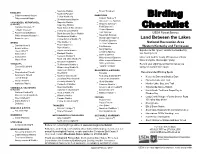

Birding Checklist

Nashville Warbler Brown Thrasher*† KINGLETS Northern Parula*† Golden-crowned Kinglet EMBERIZIDS Yellow Warbler*† Eastern Towhee*† Birding Ruby-crowned Kinglet Chestnut-sided Warbler American Tree Sparrow CHICKADEES, NUTHATCHES, Magnolia Warbler Chipping Sparrow*† & ALLIES Cape May Warbler Field Sparrow*† Carolina Chickadee*† Black-throated Blue Warbler Checklist Vesper Sparrow Tufted Titmouse*† Yellow-rumped Warbler Lark Sparrow Red-breasted Nuthatch Black-throated Green Warbler USDA Forest Service Savannah Sparrow White-breasted Nuthatch*† Blackburnian Warbler Grasshopper Sparrow Brown Creeper Yellow-throated Warbler*† Land Between the Lakes Henslow’s Sparrow Pine Warbler*† WRENS Le Conte’s Sparrow National Recreation Area Prairie Warbler*† Carolina Wren*† Fox Sparrow Western Kentucky and Tennessee Palm Warbler Bewick’s Wren Song Sparrow Bay-breasted Warbler Experience this “green” corridor surrounded by House Wren*† Lincoln’s Sparrow Winter Wren Blackpoll Warbler two flowing rivers. Swamp Sparrow Cerulean Warbler*† Sedge Wren White-throated Sparrow Listen and look for nearly 250 species of birds Black-and-white Warbler*† Marsh Wren White-crowned Sparrow travel along the Mississippi Flyway. American Redstart*† Dark-eyed Junco THRUSHES Prothonotary Warbler*† Record your sightings on this bird list as you Eastern Bluebird*† Lapland Longspur surround yourself with nature. Worm-eating Warbler*† Veery Swainson’s Warbler BLACKBIRDS & ORIOLES Gray-cheeked Thrush Ovenbird*† Bobolink -

Standard Abbreviations for Common Names of Birds M

Standard abbreviations for common names of birds M. Kathleen Klirnkiewicz I and Chandler $. I•obbins 2 During the past two decadesbanders have taken The system we proposefollows five simple rules their work more seriouslyand have begun record- for abbreviating: ing more and more informationregarding the birds they are banding. To facilitate orderly record- 1. If the commonname is a singleword, use the keeping,bird observatories(especially Manomet first four letters,e.g., Canvasback, CANV. and Point Reyes)have developedstandard record- 2. If the common name consistsof two words, use ing forms that are now available to banders.These the first two lettersof the firstword, followed by forms are convenientfor recordingbanding data the first two letters of the last word, e.g., manually, and they are designed to facilitate Common Loon, COLO. automateddata processing. 3. If the common name consists of three words Because errors in species codes are frequently (with or without hyphens),use the first letter of detectedduring editing of bandingschedules, the the first word, the first letter of the secondword, Bird BandingOffices feel that bandersshould use and the first two lettersof the third word, e.g., speciesnames or abbreviationsthereof rather than Pied-billed Grebe, PBGR. only the AOU or speciescode numbers on their field sheets.Thus, it is essentialthat any recording 4. If the common name consists of four words form have provision for either common names, (with or without hypens), use the first letter of Latin names, or a suitable abbreviation. Most each word, •.g., Great Black-backed Gull, recordingforms presentlyin use have a 4-digit GBBG. -

By Joseph T. Leverich, Boston the Northern Waterthrush (Seiurus Noveboriensis) and the Louisiana Water- Thrush (Seiurus Motacill

FIELD IDENTIFICATION NOTES: THE TWO WATERTHRUSHES by Joseph T. Leverich, Boston The Northern Waterthrush (Seiurus noveboriensis) and the Louisiana Water- thrush (Seiurus Motacilla) occur r^gularly in Massachusetts both as Mi- grants and as suMMer residents. Although extreMe individuáis of these two species are easily identified by sight, other interMediate birds can be quite cbnfusing. This article suMMarizes inforMation bearing on the field identification of the two waterthrushes, Binford (l9TlJl) states that "the ornithological literature is confusing and Misleading. Field guides vary considerably as to which characters are mentioned or stressed, and none adequately depicts the subtle dif- ferences betveen the two species. Most guides overeMphasize the throat spotting, incorrectly describe the eyeline, and fail to Mention the flank color." Habitat Where the two species overlap in range they tend to occupy different háb itats, the Northern in bogs along the edges of sMall pools (still water), and the Louisiana next to brooks and sMall streaMs (running water). Thus, both spec.ies are seen Most often in places of deep shade. Crooked Pond, Boxford^' where both occur in cióse proxiMity, is Marvelously glooMy. Unfortunately, those visual field marks that sepárate the two species have to do with tints of grey, buff and yellow. I have always counted Myself lucky to view either species in enough light to see that the back color is brown and not black. DeterMination of the ground color of the underparts was beyond the palé. Henee, this article concludes with a discussion of the territorial songs and cali notes of the two species, both of which are absolutely diagnostic.