Apollinaire and the Whatnots

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Redalyc.Giorgio Morandi and the “Return to Order”: from Pittura

Anales del Instituto de Investigaciones Estéticas ISSN: 0185-1276 [email protected] Instituto de Investigaciones Estéticas México AGUIRRE, MARIANA Giorgio Morandi and the “Return to Order”: From Pittura Metafisica to Regionalism, 1917- 1928 Anales del Instituto de Investigaciones Estéticas, vol. XXXV, núm. 102, 2013, pp. 93-124 Instituto de Investigaciones Estéticas Distrito Federal, México Available in: http://www.redalyc.org/articulo.oa?id=36928274005 How to cite Complete issue Scientific Information System More information about this article Network of Scientific Journals from Latin America, the Caribbean, Spain and Portugal Journal's homepage in redalyc.org Non-profit academic project, developed under the open access initiative MARIANA AGUIRRE laboratorio sensorial, guadalajara Giorgio Morandi and the “Return to Order”: From Pittura Metafisica to Regionalism, 1917-1928 lthough the art of the Bolognese painter Giorgio Morandi has been showcased in several recent museum exhibitions, impor- tant portions of his trajectory have yet to be analyzed in depth.1 The factA that Morandi’s work has failed to elicit more responses from art historians is the result of the marginalization of modern Italian art from the history of mod- ernism given its reliance on tradition and closeness to Fascism. More impor- tantly, the artist himself favored a formalist interpretation since the late 1930s, which has all but precluded historical approaches to his work except for a few notable exceptions.2 The critic Cesare Brandi, who inaugurated the formalist discourse on Morandi, wrote in 1939 that “nothing is less abstract, less uproot- ed from the world, less indifferent to pain, less deaf to joy than this painting, which apparently retreats to the margins of life and interests itself, withdrawn, in dusty kitchen cupboards.”3 In order to further remove Morandi from the 1. -

Futurism-Anthology.Pdf

FUTURISM FUTURISM AN ANTHOLOGY Edited by Lawrence Rainey Christine Poggi Laura Wittman Yale University Press New Haven & London Disclaimer: Some images in the printed version of this book are not available for inclusion in the eBook. Published with assistance from the Kingsley Trust Association Publication Fund established by the Scroll and Key Society of Yale College. Frontispiece on page ii is a detail of fig. 35. Copyright © 2009 by Yale University. All rights reserved. This book may not be reproduced, in whole or in part, including illustrations, in any form (beyond that copying permitted by Sections 107 and 108 of the U.S. Copyright Law and except by reviewers for the public press), without written permission from the publishers. Designed by Nancy Ovedovitz and set in Scala type by Tseng Information Systems, Inc. Printed in the United States of America by Sheridan Books. Library of Congress Cataloging-in-Publication Data Futurism : an anthology / edited by Lawrence Rainey, Christine Poggi, and Laura Wittman. p. cm. Includes bibliographical references and index. ISBN 978-0-300-08875-5 (cloth : alk. paper) 1. Futurism (Art) 2. Futurism (Literary movement) 3. Arts, Modern—20th century. I. Rainey, Lawrence S. II. Poggi, Christine, 1953– III. Wittman, Laura. NX456.5.F8F87 2009 700'.4114—dc22 2009007811 A catalogue record for this book is available from the British Library. This paper meets the requirements of ANSI/NISO Z39.48–1992 (Permanence of Paper). 10 9 8 7 6 5 4 3 2 1 CONTENTS Acknowledgments xiii Introduction: F. T. Marinetti and the Development of Futurism Lawrence Rainey 1 Part One Manifestos and Theoretical Writings Introduction to Part One Lawrence Rainey 43 The Founding and Manifesto of Futurism (1909) F. -

Aksenov BOOK

Other titles in the Södertörn Academic Studies series Lars Kleberg (Stockholm) is Professor emeritus of Russian at Södertörn University. He has published numerous Samuel Edquist, � �uriks fotspår: �m forntida svenska articles on Russian avant-garde theater, Russian and österledsfärder i modern historieskrivning, 2012. Polish literature. His book �tarfall: � �riptych has been translated into fi ve languages. In 2010 he published a Jonna Bornemark (ed.), �henomenology of �ros, 2012. literary biography of Anton Chekhov, �jechov och friheten Jonna Bornemark and Hans Ruin (eds.), �mbiguity of ([Chekhov and Freedom], Stockholm: Natur & Kultur). the �acred, forthcoming. Aleksei Semenenko (Stockholm) is Research fellow at Håkan Nilsson (ed.), �lacing �rt in the �ublic the Slavic Department of Stockholm University. He is the �ealm, 2012. author of �ussian �ranslations of �amlet and �iterary �anon �ormation (Stockholm University, 2007), �he Per Bolin, �etween �ational and �cademic �gendas, �exture of �ulture: �n �ntroduction to �uri �otman’s forthcoming. �emiotic �heory (Basingstoke: Palgrave Macmillan, 2012), and articles on Russian culture, translation and semiotics. Ларс Клеберг (Стокгольм) эмерит-профессор Седертoрнского университета, чьи многочисленные публикации посвящены театру русского авангарда и русской и польской литературе. Его книга Звездопад. Триптих была переведена на пять языков. В 2010 году вышла его биография А. П. Чехова �jechov och friheten [«Чехов и свобода»]. Алексей Семененко (Стокгольм) научный сотрудник Славянского института Стокгольмского университета, автор монографий �ussian �ranslations of �amlet and �iterary �anon �ormation и �he �exture of �ulture: �n �ntroduction to �uri �otman’s �emiotic �heory, а также работ по русской культуре, переводу и семиотике. Södertörns högskola [email protected] www.sh.se/publications Other titles in the Södertörn Academic Studies series Lars Kleberg (Stockholm) is Professor emeritus of Russian at Södertörn University. -

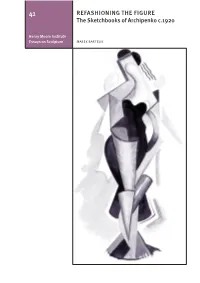

REFASHIONING the FIGURE the Sketchbooks of Archipenko C.1920

41 REFASHIONING THE FIGURE The Sketchbooks of Archipenko c.1920 Henry Moore Institute Essays on Sculpture MAREK BARTELIK 2 3 REFASHIONING THE FIGURE The Sketchbooks of Archipenko c.19201 MAREK BARTELIK Anyone who cannot come to terms with his life while he is alive needs one hand to ward off a little his despair over his fate…but with his other hand he can note down what he sees among the ruins, for he sees different (and more) things than the others: after all, he is dead in his own lifetime, he is the real survivor.2 Franz Kafka, Diaries, entry on 19 October 1921 The quest for paradigms in modern art has taken many diverse paths, although historians have underplayed this variety in their search for continuity of experience. Since artists in their studios produce paradigms which are then superseded, the non-linear and heterogeneous development of their work comes to define both the timeless and the changing aspects of their art. At the same time, artists’ experience outside of their workplace significantly affects the way art is made and disseminated. The fate of artworks is bound to the condition of displacement, or, sometimes misplacement, as artists move from place to place, pledging allegiance to the old tradition of the wandering artist. What happened to the drawings and watercolours from the three sketchbooks by the Ukrainian-born artist Alexander Archipenko presented by the Henry Moore Institute in Leeds is a poignant example of such a fate. Executed and presented in several exhibitions before the artist moved from Germany to the United States in the early 1920s, then purchased by a private collector in 1925, these works are now being shown to the public for the first time in this particular grouping. -

Futurismo : 1909-1944 / Claudia Salaris

1895 Lucini, Gian Pietro Gian Pietro da Core / G.P. Lucini. - Milano : Galli, 1895. - XII, 261 p., [1] c. di tav. ; 19 cm. Prima del tit.: Storia della evoluzione della idea. 1900 Buzzi, Paolo Il miracolo della parete : commedia in due sintesi in versi / Paolo Buzzi. - Milano : Associazione di propaganda per il risparmio e la previdenza, [1900?] [19--?]. - 47 p. ; 18 cm. Cappa, Innocenzo Pagine staccate / Innocenzo Cappa ; raccolte da Terenzio Grandi ; con una lettera dell'autore e una nota biografica. - Bari : Humanitas, [1900?] [19--?]. - 329 p., [ritr.] ; 21 cm. Lucini, Gian Pietro Filosofi ultimi : rassegna a volo d'aquila del Melibeo controllata da G.P. Lucini : contributo ad una storia della filosofia contemporanea / Gian Pietro Lucini. - Roma : Libreria politica moderna, [1900?] [19--?]. - VIII, 243 p. ; 21 cm. - (Arte, scienza, filosofia / [Libreria politica moderna] ; 1). Lucini, Gian Pietro Poesie scelte / G.P. Lucini. - Milano : ISEDI, [1900?] [19--?]. - 207 p. ; 10 cm. - (Raccolta di breviari intellettuali ; 72). Mallarmé, Stéphane Versi e prose / Mallarmé ; prima traduzione italiana di F.T. Marinetti. - Milano : Istituto Editoriale Italiano, [1900?] [19--?]. - 173 p. ; 10 cm. - (Raccolta di breviari intellettuali ; 24). Poe, Edgar Allan Racconti straordinari / Edgardo Poe ; traduzione di Decio Cinti ; illustrazioni di Arnaldo Ginna. - Milano : Facchi, [1900?] [19--?]. - 268 p. : ill. ; 24 cm. Pratella, Francesco Balilla Un prologo all'opera in due atti per il teatro dei fanciulli La ninna nanna della bambola / F. Balilla Pratella. - Ravenna : STEM, [1900?] [19--?]. - 14 p. ; 19 cm. Dati della cop. 1903 Govoni, Corrado Le fiale / Corrado Govoni. - Firenze : Lumachi, 1903. - 223 p. ; 25 cm. Marinetti, Filippo Tommaso Gabriele D'Annunzio intime / F. -

Nationalism and Regionalism In

Nationalism and Regionalism in the Art of Ardengo Soffici 1907-1938 HELEN MARAH DUDLEY A thesis submitted to the Department of Art History in conformity with the requirernents for the degree of Master of Arts Queen's University Kingston, Ontario, Canada September, 1998 copyright O Helen Marah Dudley, 1998 National Library Bibliothèque nationale du Canada Acquisitions and Acquisitions et Bibliographie Services services bibiiographiques 395 Wellington Street 395, rue Wellington Oîtawa ON K1A ON4 OttawaON K1AW CaMda canada The author has granted a non- L'auteur a accordé une licence non exclusive Licence allowing the exclusive permettant à la National Library of Canada to Biblotheque nationale du Canada de reproduce, loan, distribute or sell reproduire, prêter, distribuer ou copies of this thesis in microform, vendre des copies de cette thèse sous paper or electronic formats. la forme de microfiche/film, de reproduction sur papier ou sur format électronique. The author retains ownership of the L'auteur conserve la propriété du copwght in this thesis. Neither the droit d'auteur qui protège cette thèse. thesis nor substantial extracts fiom it Ni la thèse ni des extraits substantiels may be printed or otherwise de celle-ci ne doivent être imprimés reproduced without the author's ou autrement reproduits sans son permission. autorisation. ABSTRACT This thesis will examine the pre and post World War One cultural politics and anistic output of the Florentine artist, art critic, and author Ardengo Soffici ( 1879-1 96.0. Soffici is perhaps best known for his cubist inspired art and contact with the avant-garde circle of Pablo Picasso and Georges Braque. -

Filippo Tommaso Marinetti Correspondence and Papers, 1886-1974, Bulk 1900-1944

http://oac.cdlib.org/findaid/ark:/13030/kt6k4037tr No online items Finding aid for the Filippo Tommaso Marinetti correspondence and papers, 1886-1974, bulk 1900-1944 Finding aid prepared by Annette Leddy. 850702 1 Descriptive Summary Title: Filippo Tommaso Marinetti correspondence and papers Date (inclusive): 1886-1974 (bulk 1900-1944) Number: 850702 Creator/Collector: Marinetti, Filippo Tommaso, 1876-1944 Physical Description: 8.5 linear feet(16 boxes) Repository: The Getty Research Institute Special Collections 1200 Getty Center Drive, Suite 1100 Los Angeles, California, 90049-1688 (310) 440-7390 Abstract: Writer and founder and leader of the Italian Futurist movement. Correspondence, writings, photographs, and printed matter from Filippo Tommaso Marinetti's papers, documenting the history of the futurist movement from its beginning in the journal Poesia, through World War I, and less comprehensively, through World War II and its aftermath. Request Materials: Request access to the physical materials described in this inventory through the catalog record for this collection. Click here for the access policy . Language: Collection material is in English Biographical/Historical Note Filippo Tommaso Marinetti, born in Alexandria in 1876, attended secondary school and university in France, where he began his literary career. After gaining some success as a poet, he founded and edited the journal Poesia (1905), a forum in which the theories of futurism rather quickly evolved. With "Fondazione e Manifesto del Futurismo," published in Le Figaro (1909), Marinetti launched what was arguably the first 20th century avant-garde movement, anticipating many of the issues of Dada and Surrealism. Like other avant-garde movements, futurism took the momentous developments in science and industry as signaling a new historical era, demanding correspondingly innovative art forms and language. -

O Olhar Florentino De Ardengo Soffici Sobre O Futurismo

Rafael Zamperetti Copetti Universidade Federal de Santa Catarina [email protected] ]\ sobre o Futurismo Considering that the understanding of literary Futurism demands an approach from the interpretation of the dissonant points-of-view that com- \]- \S understanding of Futurism is problematized from the Florentine perspective as a whole. ! Considerando-se que a compreensão do Futurismo literário exige que o mesmo seja abordado a partir da interpretação dos pontos-de-vista " # \& objetivo, problematiza-se também o entendimento do Futurismo a partir da ] !] ( ) " nome que vem à tona é o do fundador do movimento, Filippo Tom- maso Marinetti. Quanto à essa tendência é sugestiva a argumentação &+1+457:;PQ Enciclopedia del novecento>+)\ encontrar obras representativas do Futurismo literário e sugere que quem de fato sobrevive nesse campo de atuação do movimento é o próprio Marinetti. Em linhas gerais, pode-se dizer que encontram-se nas palavras do estudioso sueco uma referência aos manifestos marinettianos e uma crítica aos escritores e poetas que seguiram acriticamente os seus pos- tulados. Desta forma, é licito indagar: quais foram os protagonistas do futurismo literário que efetivamente colaboraram para tornar operante " A B )" #" Fragmentos, número 36, p. 069/080 Florianópolis/ jan - jun/ 2009 PQN" N (- trar o foco de investigações a respeito de questões relativas ao Futuris- "# " o mesmo deva ser abordado sem tendências maniqueístas e sob seus mais variados prismas, de modo que assim seja possível fazer emergir a partir da fricção entre pontos de vista e visões de mundo em muitos as- NN operada por este grupo de intelectuais que ao longo de maior ou menor período de tempo e com graus variados de intensidade estiveram de al- N N+RV Cada um de nós forma-se e age no interior de instituições, pois a cultura pre- existe e sobrevive à ação do sujeito. -

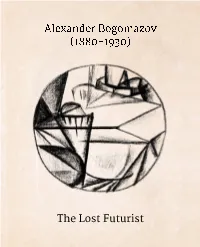

The Lost Futurist

ALEXANDER BOGOMAZOV (1880-1930) - THE LOST FUTURIST ALEXANDER Alexander Bogomazov (1880-1930) The Lost Futurist 34 Ravenscourt Road, London W6 OUG tel +44 (0)20 8748 7320 email [email protected] www.jamesbutterwick.com Self-Portrait, 1914-15 Rolling the Logs (detail), 1928-9 Alexander Bogomazov (1880-1930) The Lost Futurist 34 Ravenscourt Road, London W6 OUG tel +44 (0)20 8748 7320 email [email protected] www.jamesbutterwick.com Contents 4 Introduction by Tatiana Popova (Granddaughter of A. Bogomazov) 7 Left-hand Drive By Simon Hewitt 13 Wanda and her Family By James Butterwick 39 Kiev and Environs – The Studio Art historian Andrei Nakov recalls a visit to Kiev in 1973 85 Bogomazov and Theory – Painting and Elements By Anna Kuznetsova 107 The Caucasus 1915–1916 By James Butterwick 119 Sawyers at Work By Simon Hewitt Portrait of A Young Girl (Wanda Monastyrska), 1908 2 3 Introduction Good fortune again strikes the creative destiny Kiev: Bogomazov: Kiev is, in the plasticity of its chair sat father, deep in work... In our short moments of Alexander Bogomazov and, not for the first volume, full of beautiful diverse deep dynamism. Here of rest, we hastened into the forest. He took great time, this event is associated with Maastricht the streets are resting on the sky. Forms are elastic. interest in telling me about everything in and, in particular, TEFAF 2019. Lines are energetic. They fall, break, sing and play. the forest. James Butterwick, a passionate connoisseur Look at our stone box-houses and you will feel the of Bogomazov and an effective populariser of his amplified movement of upwards mass. -

Porter Wall List

The J. Paul Getty Trust 1200 Getty Center Drive, Suite 400 Tel 310 440 7360 Commu nications Department Los Angeles, California 90049-1681 Fax 310 440 7722 www.getty.edu [email protected] NEWS FROM THE GETTY AVAILABLE IMAGES A Tumultuous Assembly: Visual Poems of the Italian Futurists (August 1, 2006–January 7, 2007) BÏF§ZF+18 Simultaneità e chimismi lirici (A§Lot + 18 Simultaneity and Lyrical Chemistry) Florence, 1915 Ardengo Soffici (Italian, 1876-1944) Relief printing with some hand-coloring 130/300 © Eredi Soffici, Italy “Tipografia” (“Typography”) Ardengo Soffici, BÏF§ZF+18 (Florence, 1915), p. 67 Facsimile 1568-453 © Eredi Soffici, Italy “Une assemblée tumultueuse. Sensibilité numérique” (“A Tumultuous Assembly. Numerical Sensibility”) Filippo Tommaso Marinetti (Italian, 1876-1944) Les mots en liberté futuristes (Milan, 1919), p. 107 87-B6595 © 2006 Artists Rights Society (ARS), New York / SIAE, Rome “Danza Serpentina” ("Serpentine Dance") Gino Severini (Italian, 1883-1966) Lacerba (July 1, 1914), vol. 2, no. 13 , p. 202 86-S1483 © 2006 Artists Rights Society (ARS), New York / ADAGP, Paris -more- Page 2 “Deretani di Case” ("Backsides of Houses") Vincenzo Volt (Italian, 1888-1927) Archi voltaici (Milan, 1916), p. 39 90-B23637 “Après la Marne, Joffre visita le front en auto” (After the Marne, Joffre Visited the Front by Car") 1915 Filippo Tommaso Marinetti (Italian, 1876-1944) Les mots en liberté futuristes (Milan, 1919), p. 99 87-B6595 © 2006 Artists Rights Society (ARS), New York / SIAE, Rome Zang tumb tuuum Adrianopoli ottobre 1912 (Zang Tumb Tuuum: Adrianople October 1912: Words-in-Freedom) Milan, 1914 Filippo Tommaso Marinetti (Italian, 1876-1944) 85-B17320 © 2006 Artists Rights Society (ARS), New York / SIAE, Rome “Caffé Arcobaleno Liquido” ("Liquid Rainbow Café") Angelo Rognoni (Italian, 1896-1957) Fabbrica + Treno (1916), p. -

News from the Getty

The J. Paul Getty Trust 1200 Getty Center Drive, Suite 400 Tel 310 440 7360 Communications Department Los Angeles, California 90049-1681 Fax 310 440 7722 www.getty.edu [email protected] NEWS FROM THE GETTY OBJECT LIST A Tumultuous Assembly: Visual Poems of the Italian Futurists (August 1, 2006–January 7, 2007) 1. Poesia 7. Parole in libertà futuriste olfattive tattili termiche August-October 1909, vol. 5, no. 7-9, cover (Olfactory Tactile Thermal Futurist Words in 84-S826 Freedom) Rome and Savona, 1932 2. Filippo Tommaso Marinetti with Futurist Journals Filippo Tommaso Marinetti (Italian, 1876-1944) Rome, ca. 1922 Lithograph on tin Gelatin silver print 89-B4381 Photo: Luxardo Roma 850702 8. Depero futurista (Depero Futurist), 1913-1927 3. “Manifesto tecnico della letteratura futurista” Fortunato Depero (Italian, 1892-1960) (“Technical Manifesto of Futurist Literature”) Milan and Paris, 1927 Milan. 1912 87-B16665 Filippo Tommaso Marinetti (Italian, 1876-1944) 93-B14258 9. “Tipografia” (“Typography”) Ardengo Soffici, BÏF§ZF+18 (Florence, 4. “L’Immaginazione senza fili e le Parole in Libertà” 1915), p. 67 ("Imagination without strings and Words in Facsimile Freedom") 1568-453 Milan, 1913 © Eredi Soffici, Italy Filippo Tommaso Marinetti (Italian, 1876-1944) 93-B15750 10. “Danza Serpentina” ("Serpentine Dance") Gino Severini (Italian, 1883-1966) 5. “Lo splendore geometrico e meccanico nelle Lacerba (July 1, 1914), vol. 2, no. 13, p. 202 parole in libertà” 86-S1483 ("Geometric and Mechanical Splendor and in © 2006 Artists Rights Society (ARS), the Words in Freedom") New York / ADAGP, Paris Filippo Tommaso Marinetti (1876-1944) Lacerba, vol. 2, no. 6 (March 15, 1914), 11. -

Elder Cubismfuturism

BIBLIOGRAPHY to accompany CUBISMANDFUTURISM SPIRITUAL MACHINES AND THE CINEMATIC EFFECT BY R. BRUCE ELDER © 2018 Wilfrid Laurier University Press BIBLIOGRAPHY Fernand Léger: Cited Works Anthologies and Collections Abel, Richard, ed. French Film Theory and Criticism 1907–1939: A History/ Anthology, vol. 1: 1907–1929. Princeton: Princeton University Press, 1988. Léger, Fernand. Fonctions de la peinture. Paris: Éditions Denoël-Gonthier, 1965. ———. Fonctions de la peinture, ed. Sylvie Forestier. Paris: Gallimard, 1997. ———. The Functions of Painting, ed. and introduced by Edward F. Fry, trans. Alexandra Anderson. New York: Viking Press, 1973. Individual Works “Autour du Ballet mécanique” [1926]. In Fonctions de la peinture, 164–67; augmented ed., 133–39. In English: “Ballet Mécanique,” in The Functions of Painting, 48–51. “L’avenir du cinéma” [1923?] (response to a questionnaire from René Clair). Unpublished, n.d. Fernand Léger Archives, formerly Musée national Fer- nand Legér, Biot. “Charlot Cubiste” [1922?]. Film script, n.d., unpublished in Léger’s lifetime, likely written before the Ballet mécanique was made. In English: “Charlot 1 2 BIBLIOGRAPHY the Cubist.” In Patrice Blouin, Christian Delage, and Sam Stourdzé. Chaplin in Pictures (Paris: NBC Editions, 2005). Prepared as unpaginated notes for the exhibition “Chaplin in Pictures,” Jeu de Paume, Paris, 7 June–18 Sep- tember 2005. “Film by Fernand Leger and Dudley Murphy, Musical Synchronism by George Antheil.” Little Review (Autumn–Winter 1924–25): 42–44. “The Machine Aesthetic: The Manufactured Object, the Artisan, and the Art- ist.” Little Review 9, no. 3 (1923): 45–49, dedicated to Ezra Pound. Collected in The Functions of Painting, ed. Fry, 52–61.