Improving Uptake of Family Planning Services in Western Kenya: Evaluation Findings and Key Learnings

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

County Urban Governance Tools

County Urban Governance Tools This map shows various governance and management approaches counties are using in urban areas Mandera P Turkana Marsabit P West Pokot Wajir ish Elgeyo Samburu Marakwet Busia Trans Nzoia P P Isiolo P tax Bungoma LUFs P Busia Kakamega Baringo Kakamega Uasin P Gishu LUFs Nandi Laikipia Siaya tax P P P Vihiga Meru P Kisumu ga P Nakuru P LUFs LUFs Nyandarua Tharaka Garissa Kericho LUFs Nithi LUFs Nyeri Kirinyaga LUFs Homa Bay Nyamira P Kisii P Muranga Bomet Embu Migori LUFs P Kiambu Nairobi P Narok LUFs P LUFs Kitui Machakos Kisii Tana River Nyamira Makueni Lamu Nairobi P LUFs tax P Kajiado KEY County Budget and Economic Forums (CBEFs) They are meant to serve as the primary institution for ensuring public participation in public finances in order to im- Mom- prove accountability and public participation at the county level. basa Baringo County, Bomet County, Bungoma County, Busia County,Embu County, Elgeyo/ Marakwet County, Homabay County, Kajiado County, Kakamega County, Kericho Count, Kiambu County, Kilifi County, Kirin- yaga County, Kisii County, Kisumu County, Kitui County, Kwale County, Laikipia County, Machakos Coun- LUFs ty, Makueni County, Meru County, Mombasa County, Murang’a County, Nairobi County, Nakuru County, Kilifi Nandi County, Nyandarua County, Nyeri County, Samburu County, Siaya County, TaitaTaveta County, Taita Taveta TharakaNithi County, Trans Nzoia County, Uasin Gishu County Youth Empowerment Programs in urban areas In collaboration with the national government, county governments unveiled -

Facilitator's Training Manual

Department of Children's Services Facilitator’s Training Manual Implementing the Guidelines for the Alternative Family Care of Children in Kenya (2014) July 2019 This report was supported in part by Changing the Way We CareSM, a consortium of Catholic Relief Services, the Lumos Foundation, and Maestral International. Changing the Way We Care works in collaboration with donors, including the MacArthur Foundation, USAID, GHR Foundation and individuals. For more information, contact [email protected]. © 2020 This material may not be modified without the express prior written permission of the copyright holder. For permission, contact the Department of Children’s Services: P. O Box 40326- 00100 or 16936-00100, Nairobi Phone +254 (0)2729800-4, Fax +254 (0)2726222. FOREWORD The Government of Kenya’s commitment to provide for children out of family care is demonstrated by the various policies and legislative frameworks that have been developed in the recent years. All children are equal rights-holders and deserve to be within families and community as enshrined in the Constitution of Kenya 2010 and the Children Act 2001. The development of this training manual recognizes the role of the family and the community in the care of our children while the accompanying user friendly handbook aims to boost the skills and knowledge of case workers and practioners in the child protection sector. All efforts need to be made to support families to continue to care for their children and, if this is not possible, to place a child in a family-based alternative care arrangement, such as; kinship care, foster care, guardianship, Kafaalah, Supported Independent Living (SIL), or adoption. -

KENYA POPULATION SITUATION ANALYSIS Kenya Population Situation Analysis

REPUBLIC OF KENYA KENYA POPULATION SITUATION ANALYSIS Kenya Population Situation Analysis Published by the Government of Kenya supported by United Nations Population Fund (UNFPA) Kenya Country Oce National Council for Population and Development (NCPD) P.O. Box 48994 – 00100, Nairobi, Kenya Tel: +254-20-271-1600/01 Fax: +254-20-271-6058 Email: [email protected] Website: www.ncpd-ke.org United Nations Population Fund (UNFPA) Kenya Country Oce P.O. Box 30218 – 00100, Nairobi, Kenya Tel: +254-20-76244023/01/04 Fax: +254-20-7624422 Website: http://kenya.unfpa.org © NCPD July 2013 The views and opinions expressed in this report are those of the contributors. Any part of this document may be freely reviewed, quoted, reproduced or translated in full or in part, provided the source is acknowledged. It may not be sold or used inconjunction with commercial purposes or for prot. KENYA POPULATION SITUATION ANALYSIS JULY 2013 KENYA POPULATION SITUATION ANALYSIS i ii KENYA POPULATION SITUATION ANALYSIS TABLE OF CONTENTS LIST OF ACRONYMS AND ABBREVIATIONS ........................................................................................iv FOREWORD ..........................................................................................................................................ix ACKNOWLEDGEMENT ..........................................................................................................................x EXECUTIVE SUMMARY ........................................................................................................................xi -

Busia County

Sanitation Profile for 2017 Busia County Population of Busia County. Estimated percentage 953,337 21.2% of Busia population 9.6% Estimated percentage of Busia that is under 5 Years. population that is urban. Grand Score Rank Rank County (Out of 110 2 Population density 2017 2014 439/km of Busia County. points) Estimated percentage of Busia Kitui 89 1 9 91.4% population that is rural. Siaya 86 2 13 Nakuru 80 3 2 Source: 2009 Census Projections by the Kenya National Bureau of Statistics (2016). Kiambu 79 4 4 Busia 7474 5 3 Kisii 73 6 19 Machakos 71 7 5 Busia is ranked number 5 out of 47 in the county sanitation Isiolo 68 8 20 Nyeri 68 8 1 benchmarking according to the following key indicators: Homa Bay 67 10 17 Kisumu 67 10 10 E/Marakwet 66 12 10 Embu 64 13 40 Tharaka Nithi 63 14 21 Bungoma 62 15 33 Kirinyaga 61 16 5 Latrine Latrine Latrine Murang’a 61 16 8 Pupil: Pupil: Laikipia 60 18 25 Kilifi 59 19 33 Migori 58 20 14 RANK out of 47 Reporting Timely for Budget Score Sanitation /5 for Number of Score ODF Claim /10 for Cost per ODF Score Village /10 for Economic Costs of Score Poor Sanitation /10 for Score Girls /10 Coverage for Score /10 Boys Coverage for Household Improved Score Rate /15 Latrine Coverage for Number of Score facilities per Handwashing /10 school for Number of ODF Score villages (DPHO Certified /10 Targets of ODF Percent /10 Achieved Villages /10 of ODF Percent GRAND TOTAL Nyandarua 58 20 18 2014 3 5 10 10 3 5 5 15 0 10 10 8 81 Uasin Gishu 58 20 38 Kakamega 56 23 5 2017 5 0 10 10 0 8 8 5 0 10 10 10 74 Trans Nzoia 55 24 -

County Name County Code Location

COUNTY NAME COUNTY CODE LOCATION MOMBASA COUNTY 001 BANDARI COLLEGE KWALE COUNTY 002 KENYA SCHOOL OF GOVERNMENT MATUGA KILIFI COUNTY 003 PWANI UNIVERSITY TANA RIVER COUNTY 004 MAU MAU MEMORIAL HIGH SCHOOL LAMU COUNTY 005 LAMU FORT HALL TAITA TAVETA 006 TAITA ACADEMY GARISSA COUNTY 007 KENYA NATIONAL LIBRARY WAJIR COUNTY 008 RED CROSS HALL MANDERA COUNTY 009 MANDERA ARIDLANDS MARSABIT COUNTY 010 ST. STEPHENS TRAINING CENTRE ISIOLO COUNTY 011 CATHOLIC MISSION HALL, ISIOLO MERU COUNTY 012 MERU SCHOOL THARAKA-NITHI 013 CHIAKARIGA GIRLS HIGH SCHOOL EMBU COUNTY 014 KANGARU GIRLS HIGH SCHOOL KITUI COUNTY 015 MULTIPURPOSE HALL KITUI MACHAKOS COUNTY 016 MACHAKOS TEACHERS TRAINING COLLEGE MAKUENI COUNTY 017 WOTE TECHNICAL TRAINING INSTITUTE NYANDARUA COUNTY 018 ACK CHURCH HALL, OL KALAU TOWN NYERI COUNTY 019 NYERI PRIMARY SCHOOL KIRINYAGA COUNTY 020 ST.MICHAEL GIRLS BOARDING MURANGA COUNTY 021 MURANG'A UNIVERSITY COLLEGE KIAMBU COUNTY 022 KIAMBU INSTITUTE OF SCIENCE & TECHNOLOGY TURKANA COUNTY 023 LODWAR YOUTH POLYTECHNIC WEST POKOT COUNTY 024 MTELO HALL KAPENGURIA SAMBURU COUNTY 025 ALLAMANO HALL PASTORAL CENTRE, MARALAL TRANSZOIA COUNTY 026 KITALE MUSEUM UASIN GISHU 027 ELDORET POLYTECHNIC ELGEYO MARAKWET 028 IEBC CONSTITUENCY OFFICE - ITEN NANDI COUNTY 029 KAPSABET BOYS HIGH SCHOOL BARINGO COUNTY 030 KENYA SCHOOL OF GOVERNMENT, KABARNET LAIKIPIA COUNTY 031 NANYUKI HIGH SCHOOL NAKURU COUNTY 032 NAKURU HIGH SCHOOL NAROK COUNTY 033 MAASAI MARA UNIVERSITY KAJIADO COUNTY 034 MASAI TECHNICAL TRAINING INSTITUTE KERICHO COUNTY 035 KERICHO TEA SEC. SCHOOL -

County Integrated Development Plan 2018-2022 Departmental Visions and Missions Were Inspired by These Aspirations

BUSIA COUNTY COUNTY INTEGRATED DEVELOPMENT PLAN 2018 - 2022 BUSIA COUNTY VISION: A transformative and progressive County for sustainable and equitable development MISSION: To provide high quality service to Busia residents through well governed institutions and equitable resource distribution CORE VALUES: Transparency: We encourage openness in sharing information between the County Government and the public Accountability: We hold ourselves answerable to the highest ideals of professionalism, ethics and competency Integrity: We believe that acting honorably is the foundation of everything we do and the basis of public trust Teamwork: We understand the strength of cooperation and collaboration and that our success depends on our ability to work together as one cohesive team Fairness: We have an open culture and are committed to providing equal opportunities for everyone Honesty: We insist on truthfulness with each other; with the citizens, we expect and value openness Equity: We believe in fairness for every resident in distribution of resources and opportunities ii TABLE OF CONTENTS TABLE OF CONTENTS ......................................................................................................................... iii LIST OF TABLES .................................................................................................................................... x LIST OF FIGURES ................................................................................................................................. xii FOREWORD ......................................................................................................................................... -

44. Uasin Gishu

Public Disclosure Authorized Public Disclosure Authorized Public Disclosure Authorized Public Disclosure Authorized PROJECTS INCOUNTIES WORLD BANK-FUNDED KENYA WORLD BANK-FUNDED PROJECTS IN COUNTIES KENYA March, 2016 DATA SOURCE: 1. Kenya County Fact Sheets: Populaton & Populaton density - Kenya Natonal Bureau of Statstcs 2009 Census. Poverty gap Index Source: Kenya Natonal Bureau of statstcs (2012) County Poverty Trends based on WMS II (1994), WMS III. (1997bs (2005/06) and KIHBS. 2. Exchange rate US$-KSH 103 Central Bank of Kenya average July-September 2015. Disclaimer: The informaton contained in this booklet, is likely to be altered, based on changes that occur during project preparaton and implementaton. The booklet contains informaton on all actve projects in the country as of June 2015. It also captures actve regional projects that impact on various countes in Kenya. The booklet takes into account the difculty of allocatng defned amounts to countes in projects that have a natonal approach and impact. It has applied pro rata amounts as defned in each secton. However, it has not captured informaton under the following projects: EAPP-P112688, KEMP-P120014 & P145104, KEEPP103037, ESRP P083131 & P129910, EEHP -P126579, EATTFT-P079734 & NCTIPP082615, WKCDD & FMP P074106, AAIOSK-P132161, EARTTD-P148853, and KGPED-P14679. Design: Robert Waiharo Photo Credits: Isabela Gómez & Gitonga M’mbijiwe TABLE OF CONTENTS Preface .......................................................................................................................................................................................................... -

Figure1: the Map of Kenya Showing 47 Counties (Colored) and 295 Sub-Counties (Numbered)

BMJ Publishing Group Limited (BMJ) disclaims all liability and responsibility arising from any reliance Supplemental material placed on this supplemental material which has been supplied by the author(s) BMJ Global Health Additional file 1: The county and sub counties of Kenya Figure1: The map of Kenya showing 47 counties (colored) and 295 sub-counties (numbered). The extents of major lakes and the Indian Ocean are shown in light blue. The names of the counties and sub- counties corresponding to the shown numbers below the maps. List of Counties (bold) and their respective sub county (numbered) as presented in Figure 1 1. Baringo county: Baringo Central [1], Baringo North [2], Baringo South [3], Eldama Ravine [4], Mogotio [5], Tiaty [6] 2. Bomet county: Bomet Central [7], Bomet East [8], Chepalungu [9], Konoin [10], Sotik [11] 3. Bungoma county: Bumula [12], Kabuchai [13], Kanduyi [14], Kimilili [15], Mt Elgon [16], Sirisia [17], Tongaren [18], Webuye East [19], Webuye West [20] 4. Busia county: Budalangi [21], Butula [22], Funyula [23], Matayos [24], Nambale [25], Teso North [26], Teso South [27] 5. Elgeyo Marakwet county: Keiyo North [28], Keiyo South [29], Marakwet East [30], Marakwet West [31] 6. Embu county: Manyatta [32], Mbeere North [33], Mbeere South [34], Runyenjes [35] Macharia PM, et al. BMJ Global Health 2020; 5:e003014. doi: 10.1136/bmjgh-2020-003014 BMJ Publishing Group Limited (BMJ) disclaims all liability and responsibility arising from any reliance Supplemental material placed on this supplemental material which has been supplied by the author(s) BMJ Global Health 7. Garissa: Balambala [36], Dadaab [37], Dujis [38], Fafi [39], Ijara [40], Lagdera [41] 8. -

CHOLERA PREVENTION and CONTROL in KENYA Gretchen A

CHOLERA PREVENTION AND CONTROL IN KENYA Gretchen A. Cowman A dissertation submitted to the faculty of the University of North Carolina at Chapel Hill in partial fulfillment of the requirements for the degree of Doctor of Public Health in the Department of Health Policy and Management in the Gillings School of Global Public Health. Chapel Hill 2015 Approved by: Harsha Thirumurthy Suzanne Babich Jamie Bartram Michael Emch Sandra B. Greene © 2015 Gretchen A. Cowman ALL RIGHTS RESERVED ii ABSTRACT Gretchen A. Cowman: Cholera Prevention and Control in Kenya (Under the direction of Harsha Thirumurthy) Kenya experienced widespread cholera outbreaks in 1997-1999 and 2007-2010. The reemergence of cholera in Kenya in the first months of 2015 suggests that cholera remains a public health threat. This study employed a mixed methods approach to investigate the successes and challenges of cholera prevention and control in Kenya through analysis of cholera surveillance data and key informant interviews. The goal of this study was to produce information that will be useful to the Government of Kenya in establishing or strengthening policies and programs that effectively prevent and control cholera. Key findings from analysis of cholera surveillance data indicate: (1) cholera has been recurrent in various geographic regions with differing climatic conditions, (2) cholera has affected some of the least densely populated rural areas as well as Kenya’s largest cities, and (3) cholera occurrence appears to be associated with open defecation, access to improved sanitation, access to improved water sources, poverty, and level of education. Interventions, policies, and strategies that are perceived to be effective in cholera prevention and control include: (1) Community Led Total Sanitation, which aims to eliminate open defecation, (2) provision of clean water, and (3) the Integrated Disease Surveillance and Response strategy, which is Kenya’s platform for implementation of the International Health Regulations. -

Midterm Evaluation

Interim Performance Evaluation: Better Utilization Skills for Youth (BUSY) through Quality Apprenticeships in Kenya United States Department of Labor Bureau of International Labor Affairs Date: September 17, 2019 Author: Kiura Charles Munene This report was prepared for the U.S. Department of Labor (DOL) under Contract Number 1605DC-18-F-00393. The views expressed are those of the author and should not be attributed to DOL. Mention of trade names, commercial products, or organizations do not imply endorsement of them by the U.S. Government. Acknowledgments The evaluator wishes to thank most sincerely all of the people who met and consulted with the evaluation team in the course of this research, who stepped away from their busy schedules to meet with us. They include officials from the tripartite and other project partners, members of the Project Advisory Committee (PAC) and the Workplace-Based Training Coordination Committee (WBTCC), county-level officials, representatives from the informal sector (including youth working in the informal sector), and partners from the Kenya Youth Employment and Skills Program (K-YES) and the Kenya Youth Empowerment and Opportunities Project (KYEOP) and staffs. These are the true owners of the information used to synthesize this report. Special thanks go to the project staff in Nairobi for effectively managing to mobilize all the stakeholders and further for a near-seamless flow of the field mission. Their contribution to logistics was invaluable. Alongside the staff from the United States Department of Labor (USDOL), their technical inputs to the design of the evaluation were invaluable. Interim Evaluation Report: BUSY Project in Kenya ii Table of Contents ACKNOWLEDGMENTS ........................................................................................................... -

Joseph L. Awange and Obiero Ong'ang'a Lake Victoria

Joseph L. Awange and Obiero Ong'ang'a Lake Victoria Joseph L. Awange Obiero Ong'ang'a Lake Victoria Ecology, Resources, Environment With 83 Figures AUTHORS: PROF. DR. ING. DR. OBIERO ONG'ANG'A JOSEPH L. AWANGE OSIENALA (FRIENDS OF LAKE DEPARTMENT OF VICTORIA) ENVIRONMENTAL SCIENCES P.O.BOX 4580-40103 MASENO UNIVERSITY KISUMU, KENYA P.O. BOX 333 MASENO, KENYA E-mail: E-mail: [email protected] [email protected] ISBN 10 3-540-32574-3 Springer Berlin Heidelberg New York ISBN 13 978-3-540-32574-1 Springer Berlin Heidelberg New York Library of Congress Control Number: 2006924571 This work is subject to copyright. All rights are reserved, whether the whole or part of the material is concerned, specifically the rights of translation, reprinting, reuse of illustrations, recitation, broad- casting, reproduction on microfilm or in any other way, and storage in data banks. Duplication of this publication or parts thereof is permitted only under the provisions of the German Copyright Law of September 9, 1965, in its current version, and permission for use must always be obtained from Springer-Verlag. Violations are liable to prosecution under the German Copyright Law. Springer is a part of Springer Science+Business Media springeronline.com © Springer-Verlag Berlin Heidelberg 2006 Printed in The Netherlands The use of general descriptive names, registered names, trademarks, etc. in this publication does not imply, even in the absence of a specific statement, that such names are exempt from the relevant pro- tective laws and regulations and therefore free for general use. Cover design: E. Kirchner, Heidelberg Production: A. -

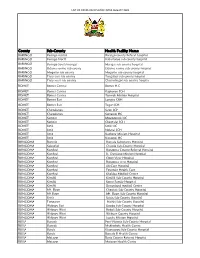

List of Covid-Vaccination Sites August 2021

LIST OF COVID-VACCINATION SITES AUGUST 2021 County Sub-County Health Facility Name BARINGO Baringo central Baringo county Referat hospital BARINGO Baringo North Kabartonjo sub county hospital BARINGO Baringo South/marigat Marigat sub county hospital BARINGO Eldama ravine sub county Eldama ravine sub county hospital BARINGO Mogotio sub county Mogotio sub county hospital BARINGO Tiaty east sub county Tangulbei sub county hospital BARINGO Tiaty west sub county Chemolingot sub county hospital BOMET Bomet Central Bomet H.C BOMET Bomet Central Kapkoros SCH BOMET Bomet Central Tenwek Mission Hospital BOMET Bomet East Longisa CRH BOMET Bomet East Tegat SCH BOMET Chepalungu Sigor SCH BOMET Chepalungu Siongiroi HC BOMET Konoin Mogogosiek HC BOMET Konoin Cheptalal SCH BOMET Sotik Sotik HC BOMET Sotik Ndanai SCH BOMET Sotik Kaplong Mission Hospital BOMET Sotik Kipsonoi HC BUNGOMA Bumula Bumula Subcounty Hospital BUNGOMA Kabuchai Chwele Sub-County Hospital BUNGOMA Kanduyi Bungoma County Referral Hospital BUNGOMA Kanduyi St. Damiano Mission Hospital BUNGOMA Kanduyi Elgon View Hospital BUNGOMA Kanduyi Bungoma west Hospital BUNGOMA Kanduyi LifeCare Hospital BUNGOMA Kanduyi Fountain Health Care BUNGOMA Kanduyi Khalaba Medical Centre BUNGOMA Kimilili Kimilili Sub-County Hospital BUNGOMA Kimilili Korry Family Hospital BUNGOMA Kimilili Dreamland medical Centre BUNGOMA Mt. Elgon Cheptais Sub-County Hospital BUNGOMA Mt.Elgon Mt. Elgon Sub-County Hospital BUNGOMA Sirisia Sirisia Sub-County Hospital BUNGOMA Tongaren Naitiri Sub-County Hospital BUNGOMA Webuye