Group Identity: Bands, Rock and Popular Music

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

2004 General Catalog

MASTERS SERIES Masters Series Lacquer Finish . Available Colors MMX MRX MHX BRX Masters Series Covered Finish . Available Colors MSX No.100 Wine Red No.400 White Marine Pearl No.102 Natural Maple No.401 Royal Gold No.103 Piano Black No.402 Abalone No.112 Natural Birch No.403 Red Onyx No.122 Black Mist No.404 Amethyst No.128 Vintage Sunburst No.141 Red Mahogany No.148 Emerald Fade No.151 Platinum Mist PEARL DRUMS No.152 Antique Gold No.153 Sunrise Fade m No.154 Midnight Fade o c . No.156 Purple Storm m No.160 Silver Sparkle u r d No.165 Diamond Burst l r No.166 Black Sparkle a e p No.168 Ocean Sparkle . w w w SESSION / EXPORT / FORUM / RHYTHM TRAVELER . Lacquer Finish Available Colors SMX SBX ELX Covered Finish Available Colors EXR EX FX RT www.pearldrum.com No.281 Carbon Mist No.430 Prizm Blue No.290 Vintage Fade No.431 Strata Black No.291 Cranberry Fade No.432 Prizm Purple No.292 Marine Blue Fade No.433 Strata White No.296 Green Burst No.21 Smokey Chrome No.280 Vintage Wine No.31 Jet Black No.283 Solid Black No.33 Pure White No.284 Tobacco Burst No.49 Polished Chrome No.289 Blue Burst No.78 Teal Metallic No.271 Ebony Mist No.91 Red Wine No.273 Blue Mist No.95 Deep Blue No.274 Amber Mist No.98 Charcoal Metallic No.294 Amber Fade No.295 Ruby Fade No.299 Cobalt Fade For more information on these or any Pearl product, visit your local authorized Pearl Dealer. -

Papeete, Tahiti

Global Aviation M A G A Z I N E Issue 69/ May 2016 Page 1 - Introduction Welcome on board this Global Aircraft. In this issue of the Global Aviation Magazine, we will take a look at two more Global Lines cities Vancouver, British Columbia, Canada and Papeete, Tahiti. We also take another look at a featured aircraft in the Global Fleet. This month’s featured aircraft is the Embraer ERJ-145. We wish you a pleasant flight. 2. Vancouver, B.C., Canada – West Meets Best 4. Papeete, Tahiti – Pacific Paradise 6. Pilot Information 8. Introducing the Embraer ERJ-145LR – With All the Frills 10. In-flight Movies/Featured Music Page 2 – Vancouver, British Columbia, Canada – West Meets Best Vancouver is a coastal city located in the Lower Mainland of British Columbia, Canada. It is named for British Captain George Vancouver, who explored and first mapped the area in the 1790s. The metropolitan area is the most populous in Western Canada and the third-largest in the country, with the city proper ranked eighth among Canadian cities. According to the 2006 census Vancouver had a population of 578,041 and just over 2.1 million people resided in its metropolitan area. Over the last 30 years, immigration has dramatically increased, making the city more ethnically and linguistically diverse; 52% do not speak English as their first language. Almost 30% of the city's inhabitants are of Chinese heritage. From a logging sawmill established in 1867 a settlement named Gastown grew, around which a town site named Granville arose. With the announcement that the railhead would reach the site, it was renamed "Vancouver" and incorporated as a city in 1886. -

Is Hip Hop Dead?

IS HIP HOP DEAD? IS HIP HOP DEAD? THE PAST,PRESENT, AND FUTURE OF AMERICA’S MOST WANTED MUSIC Mickey Hess Library of Congress Cataloging-in-Publication Data Hess, Mickey, 1975- Is hip hop dead? : the past, present, and future of America’s most wanted music / Mickey Hess. p. cm. Includes bibliographical references and index. ISBN-13: 978-0-275-99461-7 (alk. paper) 1. Rap (Music)—History and criticism. I. Title. ML3531H47 2007 782.421649—dc22 2007020658 British Library Cataloguing in Publication Data is available. Copyright C 2007 by Mickey Hess All rights reserved. No portion of this book may be reproduced, by any process or technique, without the express written consent of the publisher. Library of Congress Catalog Card Number: 2007020658 ISBN-13: 978-0-275-99461-7 ISBN-10: 0-275-99461-9 First published in 2007 Praeger Publishers, 88 Post Road West, Westport, CT 06881 An imprint of Greenwood Publishing Group, Inc. www.praeger.com Printed in the United States of America The paper used in this book complies with the Permanent Paper Standard issued by the National Information Standards Organization (Z39.48–1984). 10987654321 CONTENTS ACKNOWLEDGMENTS vii INTRODUCTION 1 1THE RAP CAREER 13 2THE RAP LIFE 43 3THE RAP PERSONA 69 4SAMPLING AND STEALING 89 5WHITE RAPPERS 109 6HIP HOP,WHITENESS, AND PARODY 135 CONCLUSION 159 NOTES 167 BIBLIOGRAPHY 179 INDEX 187 ACKNOWLEDGMENTS The support of a Rider University Summer Fellowship helped me com- plete this book. I want to thank my colleagues in the Rider University English Department for their support of my work. -

Lista MP3 Por Genero

Rock & Roll 1955 - 1956 14668 17 - Bill Justis - Raunchy (Album: 247 en el CD: MP3Albms020 ) (Album: 793 en el CD: MP3Albms074 ) 14669 18 - Eddie Cochran - Summertime Blues 14670 19 - Danny and the Juniors - At The Hop 2561 01 - Bony moronie (Popotitos) - Williams 11641 01 - Rock Around the Clock - Bill Haley an 14671 20 - Larry Williams - Bony Moronie 2562 02 - Around the clock (alrededor del reloj) - 11642 02 - Long Tall Sally - Little Richard 14672 21 - Marty Wilde - Endless Sleep 2563 03 - Good golly miss molly (La plaga) - Bla 11643 03 - Blue Suede Shoes - Carl Perkins 14673 22 - Pat Boone - A Wonderful Time Up Th 2564 04 - Lucile - R Penniman-A collins 11644 04 - Ain't that a Shame - Pat Boone 14674 23 - The Champs - Tequila 2565 05 - All shock up (Estremecete) - Blockwell 11645 05 - The Great Pretender - The Platters 14675 24 - The Teddy Bears - To Know Him Is To 2566 06 - Rockin' little angel (Rock del angelito) 11646 06 - Shake, Rattle and Roll - Bill Haley and 2567 07 - School confidential (Confid de secund 11647 07 - Be Bop A Lula - Gene Vincent 1959 2568 08 - Wake up little susie (Levantate susani 11648 08 - Only You - The Platters (Album: 1006 en el CD: MP3Albms094 ) 2569 09 - Don't be cruel (No seas cruel) - Black 11649 09 - The Saints Rock 'n' Roll - Bill Haley an 14676 01 - Lipstick on your collar - Connie Franci 2570 10 - Red river rock (Rock del rio rojo) - Kin 11650 10 - Rock with the Caveman - Tommy Ste 14677 02 - What do you want - Adam Faith 2571 11 - C' mon everydody (Avientense todos) 11651 11 - Tweedle Dee - Georgia Gibbs 14678 03 - Oh Carol - Neil Sedaka 2572 12 - Tutti frutti - La bastrie-Penniman-Lubin 11652 12 - I'll be Home - Pat Boone 14679 04 - Venus - Frankie Avalon 2573 13 - What'd I say (Que voy a hacer) - R. -

"World Music" and "World Beat" Designations Brad Klump

Document généré le 26 sept. 2021 17:23 Canadian University Music Review Revue de musique des universités canadiennes Origins and Distinctions of the "World Music" and "World Beat" Designations Brad Klump Canadian Perspectives in Ethnomusicology Résumé de l'article Perspectives canadiennes en ethnomusicologie This article traces the origins and uses of the musical classifications "world Volume 19, numéro 2, 1999 music" and "world beat." The term "world beat" was first used by the musician and DJ Dan Del Santo in 1983 for his syncretic hybrids of American R&B, URI : https://id.erudit.org/iderudit/1014442ar Afrobeat, and Latin popular styles. In contrast, the term "world music" was DOI : https://doi.org/10.7202/1014442ar coined independently by at least three different groups: European jazz critics (ca. 1963), American ethnomusicologists (1965), and British record companies (1987). Applications range from the musical fusions between jazz and Aller au sommaire du numéro non-Western musics to a marketing category used to sell almost any music outside the Western mainstream. Éditeur(s) Canadian University Music Society / Société de musique des universités canadiennes ISSN 0710-0353 (imprimé) 2291-2436 (numérique) Découvrir la revue Citer cet article Klump, B. (1999). Origins and Distinctions of the "World Music" and "World Beat" Designations. Canadian University Music Review / Revue de musique des universités canadiennes, 19(2), 5–15. https://doi.org/10.7202/1014442ar All Rights Reserved © Canadian University Music Society / Société de musique Ce document est protégé par la loi sur le droit d’auteur. L’utilisation des des universités canadiennes, 1999 services d’Érudit (y compris la reproduction) est assujettie à sa politique d’utilisation que vous pouvez consulter en ligne. -

Harmonic Resources in 1980S Hard Rock and Heavy Metal Music

HARMONIC RESOURCES IN 1980S HARD ROCK AND HEAVY METAL MUSIC A thesis submitted to the College of the Arts of Kent State University in partial fulfillment of the requirements for the degree of Master of Arts in Music Theory by Erin M. Vaughn December, 2015 Thesis written by Erin M. Vaughn B.M., The University of Akron, 2003 M.A., Kent State University, 2015 Approved by ____________________________________________ Richard O. Devore, Thesis Advisor ____________________________________________ Ralph Lorenz, Director, School of Music _____________________________________________ John R. Crawford-Spinelli, Dean, College of the Arts ii Table of Contents LIST OF FIGURES ............................................................................................................................... v CHAPTER I........................................................................................................................................ 1 INTRODUCTION ........................................................................................................................... 1 GOALS AND METHODS ................................................................................................................ 3 REVIEW OF RELATED LITERATURE............................................................................................... 5 CHAPTER II..................................................................................................................................... 36 ANALYSIS OF “MASTER OF PUPPETS” ...................................................................................... -

Smash Hits Volume 60

35p USA $1 75 March I9-April 1 1981 W I including MIND OFATOY RESPECTABLE STREE CAR TROUBLE TOYAH _ TALKING HEADS in colour FREEEZ/LINX BEGGAR &CO , <0$& Of A Toy Mar 19-Apr 1 1981 Vol. 3 No. 6 By Visage on Polydor Records My painted face is chipped and cracked My mind seems to fade too fast ^Pg?TF^U=iS Clutching straws, sinking slow Nothing less, nothing less A puppet's motion 's controlled by a string By a stranger I've never met A nod ofthe head and a pull of the thread on. Play it I Go again. Don't mind me. just work here. I don't know. Soon as a free I can't say no, can't say no flexi-disc comes along, does anyone want to know the poor old intro column? Oh, no. Know what they call me round here? Do you know? The flannel panel! The When a child throws down a toy (when child) humiliation, my dears, would be the finish of a more sensitive column. When I was new you wanted me (down me) Well, I can see you're busy so I won't waste your time. I don't suppose I can drag Now I'm old you no longer see you away from that blessed record long enough to interest you in the Ritchie (now see) me Blackmore Story or part one of our close up on the individual members of The Jam When a child throws down a toy (when toy) (and Mark Ellen worked so hard), never mind our survey of the British funk scene. -

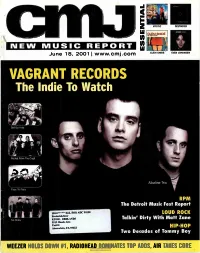

VAGRANT RECORDS the Lndie to Watch

VAGRANT RECORDS The lndie To Watch ,Get Up Kids Rocket From The Crypt Alkaline Trio Face To Face RPM The Detroit Music Fest Report 130.0******ALL FOR ADC 90198 LOUD ROCK Frederick Gier KUOR -REDLANDS Talkin' Dirty With Matt Zane No Motiv 5319 Honda Ave. Unit G Atascadero, CA 93422 HIP-HOP Two Decades of Tommy Boy WEEZER HOLDS DOWN el, RADIOHEAD DOMINATES TOP ADDS AIR TAKES CORE "Tommy's one of the most creative and versatile multi-instrumentalists of our generation." _BEN HARPER HINTO THE "Geggy Tah has a sleek, pointy groove, hitching the melody to one's psyche with the keen handiness of a hat pin." _BILLBOARD AT RADIO NOW RADIO: TYSON HALLER RETAIL: ON FEDDOR BILLY ZARRO 212-253-3154 310-288-2711 201-801-9267 www.virginrecords.com [email protected] [email protected] [email protected] 2001 VIrg. Records Amence. Inc. FEATURING "LAPDFINCE" PARENTAL ADVISORY IN SEARCH OF... EXPLICIT CONTENT %sr* Jeitetyr Co owe Eve« uuwEL. oles 6/18/2001 Issue 719 • Vol 68 • No 1 FEATURES 8 Vagrant Records: become one of the preeminent punk labels The Little Inclie That Could of the new decade. But thanks to a new dis- Boasting a roster that includes the likes of tribution deal with TVT, the label's sales are the Get Up Kids, Alkaline Trio and Rocket proving it to be the indie, punk or otherwise, From The Crypt, Vagrant Records has to watch in 2001. DEPARTMENTS 4 Essential 24 New World Our picks for the best new music of the week: An obit on Cameroonian music legend Mystic, Clem Snide, Destroyer, and Even Francis Bebay, the return of the Free Reed Johansen. -

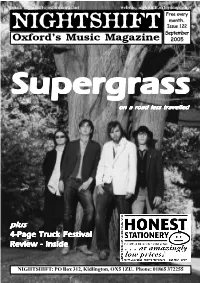

[email protected] Website: Nightshift.Oxfordmusic.Net Free Every Month

email: [email protected] website: nightshift.oxfordmusic.net Free every month. NIGHTSHIFT Issue 122 September Oxford’s Music Magazine 2005 SupergrassSupergrassSupergrass on a road less travelled plus 4-Page Truck Festival Review - inside NIGHTSHIFT: PO Box 312, Kidlington, OX5 1ZU. Phone: 01865 372255 NEWNEWSS Nightshift: PO Box 312, Kidlington, OX5 1ZU Phone: 01865 372255 email: [email protected] THE YOUNG KNIVES won You Now’, ‘Water and Wine’ and themselves a coveted slot at V ‘Gravity Flow’. In addition, the CD Festival last month after being comes with a bonus DVD which picked by Channel 4 and Virgin features a documentary following Mobile from over 1,000 new bands Mark over the past two years as he to open the festival on the Channel recorded the album, plus alternative 4 stage, alongside The Chemical versions of some tracks. Brothers, Doves, Kaiser Chiefs and The Magic Numbers. Their set was THE DOWNLOAD appears to have then broadcast by Channel 4. been given an indefinite extended Meanwhile, the band are currently in run by the BBC. The local music the studio with producer Andy Gill, show, which is broadcast on BBC recording their new single, ‘The Radio Oxford 95.2fm every Saturday THE MAGIC NUMBERS return to Oxford in November, leading an Decision’, due for release on from 6-7pm, has had a rolling impressive list of big name acts coming to town in the next few months. Transgressive in November. The monthly extension running through After their triumphant Truck Festival headline set last month, The Magic th Knives have also signed a publishing the summer, and with the positive Numbers (pictured) play at Brookes University on Tuesday 11 October. -

Precious but Not Precious UP-RE-CYCLING

The sounds of ideas forming , Volume 3 Alan Dunn, 22 July 2020 presents precious but not precious UP-RE-CYCLING This is the recycle tip at Clatterbridge. In February 2020, we’re dropping off some stuff when Brigitte shouts “if you get to the plastic section sharpish, someone’s throwing out a pile of records.” I leg it round and within seconds, eyes and brain honed from years in dank backrooms and charity shops, I smell good stuff. I lean inside, grabbing a pile of vinyl and sticking it up my top. There’s compilations with Blondie, Boomtown Rats and Devo and a couple of odd 2001: A Space Odyssey and Close Encounters soundtracks. COVER (VERSIONS) www.alandunn67.co.uk/coverversions.html For those that read the last text, you’ll enjoy the irony in this introduction. This story is about vinyl but not as a precious and passive hands-off medium but about using it to generate and form ideas, abusing it to paginate a digital sketchbook and continuing to be astonished by its magic. We re-enter the story, the story of the sounds of ideas forming, after the COVER (VERSIONS) exhibition in collaboration with Aidan Winterburn that brings together the ideas from July 2018 – December 2019. Staged at Leeds Beckett University, it presents the greatest hits of the first 18 months and some extracts from that first text that Aidan responds to (https://tinyurl.com/y4tza6jq), with me in turn responding back, via some ‘OUR PRICE’ style stickers with quotes/stats. For the exhibition, the mock-up sleeves fabricated by Tom Rodgers look stunning, turning the digital detournements into believable double-sided artefacts. -

The Sound of Ruins: Sigur Rós' Heima and the Post

CURRENT ISSUE ARCHIVE ABOUT EDITORIAL BOARD ADVISORY BOARD CALL FOR PAPERS SUBMISSION GUIDELINES CONTACT Share This Article The Sound of Ruins: Sigur Rós’ Heima and the Post-Rock Elegy for Place ABOUT INTERFERENCE View As PDF By Lawson Fletcher Interference is a biannual online journal in association w ith the Graduate School of Creative Arts and Media (Gradcam). It is an open access forum on the role of sound in Abstract cultural practices, providing a trans- disciplinary platform for the presentation of research and practice in areas such as Amongst the ways in which it maps out the geographical imagination of place, music plays a unique acoustic ecology, sensory anthropology, role in the formation and reformation of spatial memories, connecting to and reviving alternative sonic arts, musicology, technology studies times and places latent within a particular environment. Post-rock epitomises this: understood as a and philosophy. The journal seeks to balance kind of negative space, the genre acts as an elegy for and symbolic reconstruction of the spatial its content betw een scholarly w riting, erasures of late capitalism. After outlining how post-rock’s accommodation of urban atmosphere accounts of creative practice, and an active into its sonic textures enables an ‘auditory drift’ that orients listeners to the city’s fragments, the engagement w ith current research topics in article’s first case study considers how formative Canadian post-rock acts develop this concrete audio culture. [ More ] practice into the musical staging of urban ruin. Turning to Sigur Rós, the article challenges the assumption that this Icelandic quartet’s music simply evokes the untouched natural beauty of their CALL FOR PAPERS homeland, through a critical reading of the 2007 tour documentary Heima. -

What Questions Should Historians Be Asking About UK Popular Music in the 1970S? John Mullen

What questions should historians be asking about UK popular music in the 1970s? John Mullen To cite this version: John Mullen. What questions should historians be asking about UK popular music in the 1970s?. Bernard Cros; Cornelius Crowley; Thierry Labica. Community in the UK 1970-79, Presses universi- taires de Paris Nanterre, 2017, 978-2-84016-287-2. hal-01817312 HAL Id: hal-01817312 https://hal-normandie-univ.archives-ouvertes.fr/hal-01817312 Submitted on 17 Jun 2018 HAL is a multi-disciplinary open access L’archive ouverte pluridisciplinaire HAL, est archive for the deposit and dissemination of sci- destinée au dépôt et à la diffusion de documents entific research documents, whether they are pub- scientifiques de niveau recherche, publiés ou non, lished or not. The documents may come from émanant des établissements d’enseignement et de teaching and research institutions in France or recherche français ou étrangers, des laboratoires abroad, or from public or private research centers. publics ou privés. What questions should historians be asking about UK popular music in the 1970s? John Mullen, Université de Rouen Normandie, Equipe ERIAC One of the most important jobs of the historian is to find useful and interesting questions about the past, and the debate about the 1970s has partly been a question of deciding which questions are important. The questions, of course, are not neutral, which is why those numerous commentators for whom the key question is “Did the British people become ungovernable in the 1970s?” might do well to balance this interrogation with other equally non-neutral questions, such as, perhaps, “Did the British elites become unbearable in the 1970s?” My reflection shows, it is true, a preoccupation with “history from below”, but this is the approach most suited to the study of popular music history.