Konerko Reserved Tough Side While 'Good

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Tml American - Single Season Leaders 1954-2016

TML AMERICAN - SINGLE SEASON LEADERS 1954-2016 AVERAGE (496 PA MINIMUM) RUNS CREATED HOMERUNS RUNS BATTED IN 57 ♦MICKEY MANTLE .422 57 ♦MICKEY MANTLE 256 98 ♦MARK McGWIRE 75 61 ♦HARMON KILLEBREW 221 57 TED WILLIAMS .411 07 ALEX RODRIGUEZ 235 07 ALEX RODRIGUEZ 73 16 DUKE SNIDER 201 86 WADE BOGGS .406 61 MICKEY MANTLE 233 99 MARK McGWIRE 72 54 DUKE SNIDER 189 80 GEORGE BRETT .401 98 MARK McGWIRE 225 01 BARRY BONDS 72 56 MICKEY MANTLE 188 58 TED WILLIAMS .392 61 HARMON KILLEBREW 220 61 HARMON KILLEBREW 70 57 TED WILLIAMS 187 61 NORM CASH .391 01 JASON GIAMBI 215 61 MICKEY MANTLE 69 98 MARK McGWIRE 185 04 ICHIRO SUZUKI .390 09 ALBERT PUJOLS 214 99 SAMMY SOSA 67 07 ALEX RODRIGUEZ 183 85 WADE BOGGS .389 61 NORM CASH 207 98 KEN GRIFFEY Jr. 67 93 ALBERT BELLE 183 55 RICHIE ASHBURN .388 97 LARRY WALKER 203 3 tied with 66 97 LARRY WALKER 182 85 RICKEY HENDERSON .387 00 JIM EDMONDS 203 94 ALBERT BELLE 182 87 PEDRO GUERRERO .385 71 MERV RETTENMUND .384 SINGLES DOUBLES TRIPLES 10 JOSH HAMILTON .383 04 ♦ICHIRO SUZUKI 230 14♦JONATHAN LUCROY 71 97 ♦DESI RELAFORD 30 94 TONY GWYNN .383 69 MATTY ALOU 206 94 CHUCK KNOBLAUCH 69 94 LANCE JOHNSON 29 64 RICO CARTY .379 07 ICHIRO SUZUKI 205 02 NOMAR GARCIAPARRA 69 56 CHARLIE PEETE 27 07 PLACIDO POLANCO .377 65 MAURY WILLS 200 96 MANNY RAMIREZ 66 79 GEORGE BRETT 26 01 JASON GIAMBI .377 96 LANCE JOHNSON 198 94 JEFF BAGWELL 66 04 CARL CRAWFORD 23 00 DARIN ERSTAD .376 06 ICHIRO SUZUKI 196 94 LARRY WALKER 65 85 WILLIE WILSON 22 54 DON MUELLER .376 58 RICHIE ASHBURN 193 99 ROBIN VENTURA 65 06 GRADY SIZEMORE 22 97 LARRY -

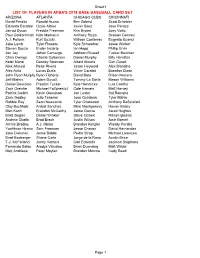

List of Players in Apba's 2018 Base Baseball Card

Sheet1 LIST OF PLAYERS IN APBA'S 2018 BASE BASEBALL CARD SET ARIZONA ATLANTA CHICAGO CUBS CINCINNATI David Peralta Ronald Acuna Ben Zobrist Scott Schebler Eduardo Escobar Ozzie Albies Javier Baez Jose Peraza Jarrod Dyson Freddie Freeman Kris Bryant Joey Votto Paul Goldschmidt Nick Markakis Anthony Rizzo Scooter Gennett A.J. Pollock Kurt Suzuki Willson Contreras Eugenio Suarez Jake Lamb Tyler Flowers Kyle Schwarber Jesse Winker Steven Souza Ender Inciarte Ian Happ Phillip Ervin Jon Jay Johan Camargo Addison Russell Tucker Barnhart Chris Owings Charlie Culberson Daniel Murphy Billy Hamilton Ketel Marte Dansby Swanson Albert Almora Curt Casali Nick Ahmed Rene Rivera Jason Heyward Alex Blandino Alex Avila Lucas Duda Victor Caratini Brandon Dixon John Ryan Murphy Ryan Flaherty David Bote Dilson Herrera Jeff Mathis Adam Duvall Tommy La Stella Mason Williams Daniel Descalso Preston Tucker Kyle Hendricks Luis Castillo Zack Greinke Michael Foltynewicz Cole Hamels Matt Harvey Patrick Corbin Kevin Gausman Jon Lester Sal Romano Zack Godley Julio Teheran Jose Quintana Tyler Mahle Robbie Ray Sean Newcomb Tyler Chatwood Anthony DeSclafani Clay Buchholz Anibal Sanchez Mike Montgomery Homer Bailey Matt Koch Brandon McCarthy Jaime Garcia Jared Hughes Brad Ziegler Daniel Winkler Steve Cishek Raisel Iglesias Andrew Chafin Brad Brach Justin Wilson Amir Garrett Archie Bradley A.J. Minter Brandon Kintzler Wandy Peralta Yoshihisa Hirano Sam Freeman Jesse Chavez David Hernandez Jake Diekman Jesse Biddle Pedro Strop Michael Lorenzen Brad Boxberger Shane Carle Jorge de la Rosa Austin Brice T.J. McFarland Jonny Venters Carl Edwards Jackson Stephens Fernando Salas Arodys Vizcaino Brian Duensing Matt Wisler Matt Andriese Peter Moylan Brandon Morrow Cody Reed Page 1 Sheet1 COLORADO LOS ANGELES MIAMI MILWAUKEE Charlie Blackmon Chris Taylor Derek Dietrich Lorenzo Cain D.J. -

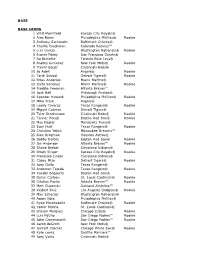

2021 Bowman Baseball Checklist .Xls

BASE BASE CARDS 1 Whit Merrifield Kansas City Royals® 2 Alec Bohm Philadelphia Phillies® Rookie 3 Anthony Santander Baltimore Orioles® 4 Charlie Blackmon Colorado Rockies™ 5 Luis Garcia Washington Nationals® Rookie 6 Buster Posey San Francisco Giants® 7 Bo Bichette Toronto Blue Jays® 8 Andres Gimenez New York Mets® Rookie 9 Trevor Bauer Cincinnati Reds® 10 Jo Adell Angels® Rookie 11 Tarik Skubal Detroit Tigers® Rookie 12 Brian Anderson Miami Marlins® 13 Sixto Sanchez Miami Marlins® Rookie 14 Freddie Freeman Atlanta Braves™ 15 Josh Bell Pittsburgh Pirates® 16 Spencer Howard Philadelphia Phillies® Rookie 17 Mike Trout Angels® 18 Leody Taveras Texas Rangers® Rookie 19 Miguel Cabrera Detroit Tigers® 20 Tyler Stephenson Cincinnati Reds® Rookie 21 Tanner Houck Boston Red Sox® Rookie 22 Max Kepler Minnesota Twins® 23 Sam Huff Texas Rangers® Rookie 24 Christian Yelich Milwaukee Brewers™ 25 Alex Bregman Houston Astros® 26 Bobby Dalbec Boston Red Sox® Rookie 27 Ian Anderson Atlanta Braves™ Rookie 28 Shane Bieber Cleveland Indians® 29 Brady Singer Kansas City Royals® Rookie 30 Francisco Lindor Cleveland Indians® 31 Casey Mize Detroit Tigers® Rookie 32 Joey Gallo Texas Rangers® 33 Anderson Tejeda Texas Rangers® Rookie 34 Xander Bogaerts Boston Red Sox® 35 Dylan Carlson St. Louis Cardinals® Rookie 36 Cristian Pache Atlanta Braves™ Rookie 37 Matt Chapman Oakland Athletics™ 38 Keibert Ruiz Los Angeles Dodgers® Rookie 39 Max Scherzer Washington Nationals® 40 Aaron Nola Philadelphia Phillies® 41 Ryan Mountcastle Baltimore Orioles® Rookie 42 Yadier Molina -

National Champions 1976, 1980, 1986 14 CWS

2002 Arizona Baseball Schedule/Results Date Opponent Time National Champions January 25 New Mexico 3 p.m. 1976, 1980, 1986 26 New Mexico 3 p.m. 27 New Mexico 1 p.m. 14 CWS Appearances February 1 Utah 3 p.m. 2002 Game Notes 2 Utah 1 p.m. 3 Utah 3 p.m. vs. New Mexico (1/25 3 p.m., 1/26 3 p.m., 1/27 1 p.m.) 4 Southern Utah 3 p.m. First Up - New Mexico: In a rivalry that dates back to 1917, Arizona and New Mexico will lock 5 Southern Utah 3 p.m. horns for the 12th straight season, Jan.25-27, in Tucson. Arizona leads the all-time series 122- 7 San Diego State 3 p.m. 28 and has won the last 14 consecutive games played between the two schools, include three 8 San Diego State 3 p.m. games last season. The Lobos went 26-34 in 2001 and 14-16 in the Mountain West Confer- 9 San Diego State 1 p.m. ence. UNM lost eight position players from last season’s team, but return seven of its nine 10 All-Pro Alumni 1 p.m. pitchers. The top two players to return for the Lobos are right-handed pitcher Jeremy DeYapp 13 at Texas A&M-Corpus Christi 7 p.m. (4-3, 4.32 ERA, 58 K’s) and second baseman Troy Cairns, Jr. (.349, 26 2B, 32 RBI). Rich Alday, 15 at Texas A&M 3 p.m. the coach who started the baseball program at Pima C.C. -

ESPN Fantasy Baseball Cheat Sheet: Roto Leagues Starting Pitchers, Cont

ESPN Fantasy Baseball cheat sheet: Roto leagues Starting pitchers, cont. First basemen Shortstops Outfielders Outfielders, cont. 51. (246) Jake Arrieta PHI 1. (15) Freddie Freeman ATL 1. (6) Alex Bregman HOU 1. (1) Mike Trout LAA 63. (226) Ramon Laureano OAK 52. (251) Nick Pivetta PHI 2. (16) Paul Goldschmidt STL 2. (7) Trea Turner WSH 2. (2) Mookie Betts BOS 64. (228) Randal Grichuk TOR 53. (255) Yusei Kikuchi SEA 3. (38) Anthony Rizzo CHC 3. (9) Francisco Lindor CLE 3. (4) J.D. Martinez BOS 65. (229) Cedric Mullins BAL 54. (256) Rich Hill LAD 4. (45) Cody Bellinger LAD 4. (13) Manny Machado SD 4. (10) Ronald Acuna Jr. ATL 66. (230) Brian Anderson MIA 55. (258) Yu Darvish CHC 5. (46) Joey Votto CIN 5. (14) Javier Baez CHC 5. (12) Christian Yelich MIL 67. (242) Nick Markakis ATL Last updated: 56. (259) Marco Gonzales SEA 6. (53) Jose Abreu CWS 6. (18) Trevor Story COL 6. (17) Aaron Judge NYY 68. (244) Jesse Winker CIN Friday, March 01, 2019 57. (263) Zack Godley ARI 7. (59) Matt Carpenter STL 7. (33) Carlos Correa HOU 7. (19) Andrew Benintendi BOS 69. (248) Ian Happ CHC 58. (264) Jon Gray COL 8. (84) Jesus Aguilar MIL 8. (48) Xander Bogaerts BOS 8. (20) Bryce Harper PHI 70. (249) Manuel Margot SD Position rank is listed first, followed by 59. (266) Julio Teheran ATL 9. (93) Edwin Encarnacion SEA 9. (51) Gleyber Torres NYY 9. (21) Kris Bryant CHC 71. (250) Daniel Palka CWS overall rank in parentheses. -

2002 NCAA Baseball and Softball Records Book

Baseball Award Winners American Baseball Coaches Association— Division I All-Americans By College.................. 140 American Baseball Coaches Association— Division I All-America Teams (1947-2001) ............. 142 Baseball America— Division I All-America Teams (1981-2001) ............. 144 Collegiate Baseball— Division I All-America Teams (1991-2001) ............. 145 American Baseball Coaches Association— Division II All-Americans By College................. 146 American Baseball Coaches Association— Division II All-America Teams (1969-2001) ............ 148 American Baseball Coaches Association— Division III All-Americans By College................ 149 American Baseball Coaches Association— Division III All-America Teams (1976-2001) ........... 151 Individual Awards .............................................. 153 140 AMERICAN BASEBALL COACHES ASSOCIATION—DIVISION I ALL-AMERICANS BY COLLEGE 97—Tim Hudson 75—Denny Walling FORDHAM (1) All-America 95—Ryan Halla 67—Rusty Adkins 97—Mike Marchiano 89—Frank Thomas 60—Tyrone Cline FRESNO ST. (12) Teams 88—Gregg Olson 59—Doug Hoffman 97—Giuseppe Chiaramonte 67—Q. V. Lowe 47—Joe Landrum 91—Bobby Jones 62—Larry Nichols COLGATE (1) 89—Eddie Zosky American Baseball BALL ST. (1) 55—Ted Carrangele Tom Goodwin Coaches 86—Thomas Howard COLORADO (2) 88—Tom Goodwin BAYLOR (6) 77—Dennis Cirbo Lance Shebelut Association 01—Kelly Shoppach 73—John Stearns John Salles 99—Jason Jennings 84—John Hoover COLORADO ST. (1) 82—Randy Graham 77—Steve Macko 77—Glen Goya DIVISION I ALL- 54—Mickey Sullivan 78—Ron Johnson AMERICANS BY COLLEGE 53—Mickey Sullivan COLUMBIA (2) 72—Dick Ruthven 84—Gene Larkin 51—Don Barnett (First-Team Selections) 52—Larry Isbell 65—Archie Roberts BOWDOIN (1) GEORGIA (1) ALABAMA (4) 53—Fred Fleming CONNECTICUT (3) 87—Derek Lilliquist 97—Roberto Vaz 63—Eddie Jones GA. -

Fox's Sun Sports Announces 150-Game Tampa Bay Rays

FOX’S SUN SPORTS ANNOUNCES 150-GAME TAMPA BAY RAYS TELEVISION SCHEDULE FOR 2015 SEASON Four spring training games Nine episodes of “Inside the Rays” Three nationally televised games on FOX Sports 1 TAMPA, Fla. (March 2, 2015) — Sun Sports, the statewide television home of the Tampa Bay Rays, announced today the network will produce and televise 150 Rays regular season games as part of the 2015 Major League Baseball season. Opening Day coverage begins live from Tropicana Field with a special 90 minute pregame show, starting at 1:30 p.m. on Monday, April 6, when the Rays host the Baltimore Orioles. Like last year, both home and away game broadcasts will feature half-hour Rays LIVE pregame shows and all will offer extended postgame coverage from site. Home games Rays LIVE will originate from Tropicana Field, while away games will air from the FOX Sports studio in Fort Lauderdale, Fla. Dewayne Staats returns this year for his 18th season as play-by-play announcer for Rays baseball on Sun Sports and will be joined in the booth by former MLB pitcher Brian Anderson. Staats enters his 38th year broadcasting baseball, while Anderson enters his 7th season providing color commentary on Sun Sports. Also in his 18th season, Todd Kalas serves as host for Rays LIVE pre- and postgame shows at Tropicana Field, while Rich Hollenberg will return for his second season anchoring away games from the FOX Sports studio. Orestes Destrade also returns in his role as analyst on Rays LIVE. Two new faces join the broadcast team this season as Tampa native Emily Austen will serve as in-game reporter and host of select “Inside the Rays” episodes, while former Rays pitcher Doug Waechter will provide in-depth pitching insight this season as analyst. -

1 Wright State Baseball

WRIGHT STATE RAIDERS • WRIGHT STATE RAIDERS • WRIGHT STATE RAIDERS • WRIGHT STATE RAIDERS • WRIGHT STATE RAIDERS • WRIGHT STATE RAIDERS • WRIGHT STATE RAIDERS • WRIGHT STATE RAIDERS • WRIGHT STATE RAIDERS • WRIGHT STATE RAIDERS • WRIGHT STATE RAIDERS • WRIGHT STATE RAIDERS • WRIGHT STATE RAIDERS • WRIGHT STATE RAIDERS • WRIGHT STATE RAIDERS • WRIGHT STAT WRIGHT STATE BASEBALL 1 WRIGHT STATE RAIDERS • WRIGHT STATE RAIDERS • WRIGHT STATE RAIDERS • WRIGHT STATE RAIDERS • WRIGHT STATE RAIDERS • WRIGHT STATE RAIDERS • WRIGHT STATE RAIDERS • WRIGHT STATE RAIDERS • WRIGHT STATE RAIDERS • WRIGHT STATE RAIDERS • WRIGHT STATE RAIDERS • WRIGHT STATE RAIDERS • WRIGHT STATE RAIDERS • WRIGHT STATE RAIDERS • WRIGHT STATE RAIDERS • WRIGHT STAT WRIGHT STATE BASEBALL 1 WRIGHT STATE RAIDERS • WRIGHT STATE RAIDERS • WRIGHT STATE RAIDERS • WRIGHT STATE RAIDERS • WRIGHT STATE RAIDERS • WRIGHT STATE RAIDERS • WRIGHT STATE RAIDERS • WRIGHT STATE RAIDERS • WRIGHT STATE RAIDERS • WRIGHT STATE RAIDERS • WRIGHT STATE RAIDERS • WRIGHT STATE RAIDERS • WRIGHT STATE RAIDERS • WRIGHT STATE RAIDERS • WRIGHT STATE RAIDERS • WRIGHT STAT All-Time Roster A Bruns, Rob ............................. 94, 96, 97, 98 Eshbaugh, Mark ..................................... 86 Abrams, Casey ........................ 01, 02, 03 Brunswick, Jeff ....................................... 89 Estepp, Ron ............................................ 71 Abusaleh, Amin .............................. 05, 06 Bruskotter, Aaron ................. 95, 96, 97, 98 Eubank, Carl ................................... -

ESPN Fantasy Baseball Cheat Sheet: Head-To-Head Points Leagues Starting Pitchers, Cont

ESPN Fantasy Baseball cheat sheet: Head-to-head points leagues Starting pitchers, cont. First basemen Shortstops Outfielders Outfielders, cont. 51. (253) Jon Lester CHC 1. (7) Freddie Freeman ATL 1. (5) Trea Turner WSH 1. (1) Mookie Betts BOS 63. (202) Domingo Santana SEA 52. (256) Robbie Erlin SD 2. (20) Paul Goldschmidt STL 2. (11) Trevor Story COL 2. (2) Mike Trout LAA 64. (205) Kevin Pillar TOR 53. (257) Mike Leake SEA 3. (29) Anthony Rizzo CHC 3. (13) Francisco Lindor CLE 3. (4) J.D. Martinez BOS 65. (207) Byron Buxton MIN 54. (265) Kevin Gausman ATL 4. (31) Cody Bellinger LAD 4. (14) Alex Bregman HOU 4. (12) Christian Yelich MIL 66. (208) Nomar Mazara TEX 55. (266) Reynaldo Lopez CWS 5. (46) Joey Votto CIN 5. (18) Javier Baez CHC 5. (15) Charlie Blackmon COL 67. (213) Ryan Braun MIL Last updated: 56. (271) Joey Lucchesi SD 6. (52) Matt Carpenter STL 6. (23) Manny Machado SD 6. (17) Ronald Acuna Jr. ATL 68. (217) Adam Eaton WSH Friday, March 08, 2019 57. (276) Nathan Eovaldi BOS 7. (56) Jose Abreu CWS 7. (41) Xander Bogaerts BOS 7. (19) Aaron Judge NYY 69. (221) Christin Stewart DET 58. (279) Zack Godley ARI 8. (65) Carlos Santana CLE 8. (42) Jean Segura PHI 8. (21) Giancarlo Stanton NYY 70. (223) Harrison Bader STL Position rank is listed first, followed by 59. (281) Robbie Ray ARI 9. (71) Edwin Encarnacion SEA 9. (57) Adalberto Mondesi KC 9. (22) Whit Merrifield KC 71. (229) Cedric Mullins BAL overall rank in parentheses. -

2020 Donruss Optic Baseball Checklist

2020 Donruss Optic Baseball Team Autograph Player Grid Purple=Fireworks; Orange=Highlights; Green=Optic; Yellow=Rated Prospect; White=Rated Rookie; Gold=Retro; Grey=Signatures Series Angels Dillon Peters Jo Adell Jo Adell Jose Suarez Matt Thaiss Patrick Sandoval Shohei Ohtani Troy Glaus Aaron Sanchez Abraham Toro Alex Bregman Alex Bregman Bryan Abreu Forrest Whitley Freudis Nova Jose Altuve Astros Jose Altuve Josh James Yordan Alvarez Yordan Alvarez Athletics A.J. Puk Jesus Luzardo Matt Chapman Rickey Henderson Sean Murphy Sean Murphy Sheldon Neuse Stephen Piscotty Anthony Kay Bo Bichette Jonathan Davis Reese McGuire Shun Yamaguchi T.J. Zeuch Thomas Pannone Vladimir Guerrero Jr. Blue Jays Vladimir Guerrero Jr. Braves Austin Riley Chipper Jones Cole Hamels Cristian Pache Drew Waters Ozzie Albies Ronald Acuna Jr. Brewers Brice Turang Corbin Burnes Corey Ray Josh Hader Trent Grisham Tyrone Taylor Austin Dean Dakota Hudson Dylan Carlson Dylan Carlson Edmundo Sosa Kwang-Hyun Kim Matthew Liberatore Nolan Gorman Cardinals Paul DeJong Randy Arozarena Tommy Edman Cubs Adbert Alzolay Anthony Rizzo Anthony Rizzo Duane Underwood Miguel Amaya Nico Hoerner Robel Garcia Diamondbacks Alek Thomas Corbin Carroll Daulton Varsho Domingo Leyba Josh Rojas Kristian Robinson Taylor Clarke Zac Gallen Clayton Kershaw Cody Bellinger Corey Seager Dustin May Edwin Rios Gavin Lux Justin Turner Luis Rodriguez Dodgers Miguel Vargas Tony Gonsolin Giants Heliot Ramos Jaylin Davis Joey Bart Juan Marichal Logan Webb Luis Matos Mauricio Dubon Mauricio Dubon Aaron Civale Adam Plutko Bobby Bradley Bobby Bradley CC Sabathia Cesar Hernandez Eric Haase Logan Allen Indians Nolan Jones Triston McKenzie Tyler Freeman Yu Chang Yu Chang Alex Rodriguez Donnie Walton Evan White Evan White Jake Fraley Jarred Kelenic Julio Rodriguez Justin Dunn Mariners Kyle Lewis Kyle Lewis Logan Gilbert Noelvi Marte Shed Long Jr. -

CHEAT SHEET for 2021 FANTASY DRAFTS 5X5 12-Team Mixed-League Cheat Sheet

CHEAT SHEET FOR 2021 FANTASY DRAFTS 5x5 12-team mixed-league cheat sheet CATCHERS SECOND BASEMEN SHORTSTOPS OUTFIELDERS STARTING PITCHERS STARTING PITCHERS RELIEF PITCHERS 25 J.T. Realmuto 33 DJ LeMahieu 50 Fernando Tatis Jr. 11 Austin Meadows 47 Gerrit Cole 1 Aaron Civale 15 Liam Hendriks 12 Salvador Perez 27 Ozzie Albies 47 Trea Turner 11 Lourdes Gurriel Jr. 46 Jacob deGrom 1 Marcus Stroman 15 Josh Hader 10 Will Smith 15 Keston Hiura 45 Trevor Story 8 Jeff McNeil 44 Shane Bieber 1 Jose Urquidy 10 Aroldis Chapman 8 Yasmani Grandal 15 Jose Altuve 40 Francisco Lindor 8 Byron Buxton 38 Lucas Giolito 1 Freddy Peralta 9 Edwin Díaz 6 Willson Contreras 15 Cavan Biggio 35 Bo Bichette 7 Wil Myers 38 Trevor Bauer 1 Jameson Taillon 9 Raisel Iglesias 5 Travis d’Arnaud 13 Brandon Lowe 33 Adalberto Mondesi 7 Alex Verdugo 37 Yu Darvish 1 Elieser Hernandez 8 James Karinchak 5 Sean Murphy 11 Ketel Marte 33 Corey Seager 6 Joey Gallo 36 Aaron Nola 1 Dustin May 8 Trevor Rosenthal 4 Gary Sánchez 7 Mike Moustakas 28 Xander Bogaerts 6 Jorge Soler 35 Walker Buehler 1 Cristian Javier 7 Ryan Pressly 3 Christian Vazquez 3 Jake Cronenworth 20 Tim Anderson 6 Tommy Pham 34 Max Scherzer 1 James Paxton 7 Brad Hand 3 Austin Nola 3 Nick Madrigal 18 Gleyber Torres 6 Kyle Lewis 33 Luis Castillo 1 John Means 6 Kenley Jansen 2 James McCann 2 Jean Segura 11 Javier Báez 6 Ramón Laureano 32 Jack Flaherty 1 Shohei Ohtani 4 Craig Kimbrel 1 Mitch Garver 1 Jonathan Villar 8 Dansby Swanson 6 Mike Yastrzemski 29 Clayton Kershaw 1 Drew Smyly 4 Alex Colomé 1 Wilson Ramos 1 Gavin Lux -

2001 NCAA Baseball and Softball Records Book

AwardsBB00 2/8/01 9:07 AM Page 137 Ba s e b a l l Awa r d Win n e r s American Baseball Coaches Association— Division I All-Americans By College.. 138 American Baseball Coaches Association— Division I All-America Teams (194 7 - 0 0 ) .. 140 Baseball America— Division I All-America Teams (1981- 0 0 ) .. 142 Collegiate Baseball— Division I All-America Teams (199 1 - 0 0 ) .. 143 American Baseball Coaches Association— Division II All-Americans By College.. 144 American Baseball Coaches Association— Division II All-America Teams (196 9 - 0 0 ) .. 146 American Baseball Coaches Association— Division III All-Americans By College.. 147 American Baseball Coaches Association— Division III All-America Teams (1976- 0 0 ) .. 149 Individual Awa rd s .. 150 AwardsBB00 2/8/01 9:07 AM Page 138 13 8 AMERICAN BASEBALL COACHES ASSOCIATION—DIVISION I ALL-AMERICANS BY COLLEGE 97 — Tim Hudson 60 — Tyrone Cline FORDHAM (1) Al l - A m e r i c a 95 — Ryan Halla 59 — Doug Hoffman 97 — Mike Marchiano 89 — Frank Thomas 47 — Joe Landrum FRESNO ST. (12) 88 — Gregg Olson Tea m s COLGATE (1) 97 — Giuseppe Chiaramonte 67 — Q. V. Lowe 55 — Ted Carrangele 91 — Bobby Jones 62 — Larry Nichols 89 — Eddie Zosky COLORADO (2) BALL ST. (1) Tom Goodwin American Baseball 77 — Dennis Cirbo 86 — Thomas Howard 88 — Tom Goodwin Co a c h e s 73 — John Stearns BAYLOR (5) Lance Shebelut As s o c i a t i o n 99—Jason Jennings COLORADO ST. (1) John Salles 77 — Steve Macko 77 — Glen Goya 84 — John Hoover 54 — Mickey Sullivan COLUMBIA (2) 82 — Randy Graham 78 — Ron Johnson DIVISION I ALL- 53 — Mickey Sullivan 84 — Gene Larkin 72 — Dick Ruthven AMERICANS BY COLLEGE 52 — Larry Isbell 65 — Archie Roberts 51 — Don Barnett (First-Team Selections) BOWDOIN (1) CONNECTICUT (3) GEORGIA (1) 53 — Fred Fleming 63 — Eddie Jones ALABAMA (4) 87 — Derek Lilliquist BRIGHAM YOUNG (10) 59 — Moe Morhardt 97 — Roberto Vaz GA.