Agricultural Workers Renfrewshire

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Renfrewshire Case Study Harnessing Renfrewshire’S Watery Wealth Overview Who? Renfrewshire Council

Renfrewshire Case Study Harnessing Renfrewshire’s Watery Wealth Overview Who? Renfrewshire Council. What? Two hydro projects, a hydro and district heating strategy, and an ambitious plan to grow willow coppices as biomass fuel on derelict industrial sites. Where? Paisley, Lochwinnoch, Renfrewshire How much? £76, 780 (development grants in total). Background Water powered the industrial revolution in Renfrewshire – and it’s now making a comeback as part of ambitious plans to beat fuel poverty. The local The council is now conducting a feasibility study to authority is using almost £20,000 of grant money from see if they can harness the water at the weir to drive a the Warm Homes Fund to explore two potential small- turbine which would supply some of the power used at scale hydro sites for electrical power generation – one Renfrewshire House, where the majority of the council’s in the centre of one of Scotland’s largest towns and the staff are based. Money generated from Feed In Tariffs other near a pretty rural village. could then be used to create a community benefits fund to provide affordable warmth to households. Also on the cards is a forward-thinking scheme to grow willow trees on derelict industrial land around the region, then use the wood to fuel biomass boilers at council buildings, as well as selling any excess on the burgeoning “ At the moment we have several schemes renewable energy market. on the go using Warm Homes Fund money, which has been wonderfully easy to access.” Renfrewshire had hundreds of water-powered mills in the 18th century – they ran the textiles industry which Ron Mould, Energy Officer (Housing), Renfrewshire Council saw Paisley pattern cloth exported across the world. -

Ayrshire & Galloway

ARCH.,EOLOGICAL H ISTORICAL COLLtrCTIONS RELATING TO AYRSHIRE & GALLOWAY VOL. VII. EDINBURGH PRINTED FOR THE AYRSHIRE AND GALLOWAY ARCH.€OLOGICAL ASSOCIATION MDCCCXCIV !a't'j j..l I Pt'inted 6y Ii. €s" Il. Clarlt !'ott DAVID DOUGLAS, EDINBURGII 300 Copies lriruted, Of zu/aiclo tlais is Uo. 7, f ( AYRSHIRE AND GALLOUIAY ARCH.TOtOGICAL ASSOCIATION {D re 5itr e nt. Tnn EARL or STAIR, K.T., LL.D., LP.S.A. Scot., Iord.-Lieutenant of Ayrshire and Wigtonshire. zrlitv--ptviiU sntE, Tirn DUKE or PORTLAND. Tnn MARQUESS or BUTE, K.'I., LL.D., F;S.A. Scot. Tnn MARQUESS ol AILSA, F.S.A. Scot. Tun EARL ol GALLOWAY, K.T. Tltn EARL or GLASGOW. THs LORD HERRIES, Lord-Lieutenant of the Stewartry. Tnn Rr. HoN. SrnJAS. FERGUSSON, B.Enr.,M.P.,G.C.S.I.,K.C.M.G.,C.I.E., LL.D. Tun Rrcnr Hos. Srn J. DALRYMPLE -HAY, Bart., C.8., D.C.L., F.R.S. Srn M. SHAW-STEWART, BAnt., Lord-Lieutenant of Renfrewshire. Sm IMILLIAM J. MOI{TGOMERY-CUNINGIIAME, Banr., Y.C., bf Corsehill. Sm HERBERT EUSTACE MAXWELL, Banr., of Monreith, M.P., F.S.A. Scot. R. A. OSWALD, Esq., of Auchincui've. ilron- Secretsries tor Tvrsbite, R. \ry. COCHRAN-PATRICK, Esq., of Woodsicle, LL.D., F.S.A., F.S.A. Scot. Tsn Hon. HEW DALRYMPLE, tr'.S,A. Scot. (for Carrick). J. SHEDDEN-DOBIE, Est1., of Morishill, F.S.A. Scot (for Cuningharne). R. MUNRO, Esc1., ILD., M.A., F.S.A. Scot. bgn, Setretarieg for fuN,igtsnsbit.e, Tqn Rnv. -

Records of the Lanarkshire and Renfrewshire Hunt

Records of the Lanarkshire and Renfrewshire Hunt HlUm'uiVi^mryTUFTS ii'S^Slt 024 287 G7 J83 Records of the Lanarkshire and Renfrewshire Hunt Records of the Lanarkshire and Renfrewshire Hunt COMPILED BY " TANTIVY » Author of " Scottish Hunts," and Contributor of Special Articles to "The Glasgow Herald" 1921 GLASGOW: PRINTED BY AIRD & COGHILL, LTD. PREFACE. ACTING upon the suggestion of the retiring Master and other prominent members of the Lanarkshire and Renfrewshire Hunt, I have ventured to produce an historical record which it is hoped will meet with the appreciation of those interested. For the description of the sport of the past twenty seasons I am greatly indebted to the diaries so perfectly kept by the late Mr. J. J. Barclay, which were kindly placed at my disposal by Mr. G. Barclay. Without such a valuable asset no work of this kind could ever have been attempted, and I have made the fullest possible use of these records, so that sportsmen and sportswomen of the last quarter of a century can refresh their memory in regard to the many great runs enjoyed during that period. I hope I have succeeded in an effort to furnish a complete and unvarnished account of the doings of the pack, together with a history of the Hunt since its origin. Possibly, at some future time, another enthusiast will take up the pen and bring the records up to date. Harry Judd (" Tantivy "). CONTENTS. PAGE The Lanarkshire and Renfrewshire Hunt, -------- 9 Group of Hounds in Kennel, 39 Presentation Ceremony at Finlaystone House, ------- 40 Meet at Barochan, -.-. -

ATM Operator Street Address Town/City Country Postcode

ATM_Operator Street Address Town/City Country Postcode YourCash HARENESS ROAD ABERDEEN SCOTLAND AB12 3LE Cardtronics UK Ltd BANKHEAD DRIVE ABERDEEN SCOTLAND AB12 4XX Cardtronics UK Ltd BRIDGE OF DEE ABERDEEN SCOTLAND AB12 5XD Cardtronics UK Ltd KINGSWELLS AVENUE ABERDEEN SCOTLAND AB15 8TG NoteMachine NORTH DEESIDE ROAD ABERDEEN SCOTLAND AB15 9DB NoteMachine HOWES ROAD ABERDEEN SCOTLAND AB16 7AG Cardtronics UK Ltd HOWE MOSS CRESCENT ABERDEEN SCOTLAND AB21 0GN Cardtronics UK Ltd THE FOLD ABERDEEN SCOTLAND AB21 0LU Cardtronics UK Ltd OLDMELDRUM ROAD ABERDEEN SCOTLAND AB21 0PJ Cardtronics UK Ltd MAIN ROAD ABERDEEN SCOTLAND AB21 0XN YourCash SCOTLAND AB21 7EA NatWest LAUREL DRIVE ABERDEEN SCOTLAND AB22 8HB Cardtronics UK Ltd ROWAN DRIVE ABERDEEN SCOTLAND AB23 8SW NoteMachine CRAIGOUR ROAD BANCHORY SCOTLAND AB31 4HE YourCash THE TERRACE WESTHILL SCOTLAND AB32 7AX Cardtronics UK Ltd MAR ROAD BALLATER SCOTLAND AB35 5YL YourCash HILL STREET ABERLOUR SCOTLAND AB38 9TB Cardtronics UK Ltd REDCLOAK DRIVE STONEHAVEN SCOTLAND AB39 2XJ NatWest NEWTONHILL ROAD STONEHAVEN SCOTLAND AB39 3PX NoteMachine THE SQUARE ELLON SCOTLAND AB41 7GX Cardtronics UK Ltd PITMEDDEN ELLON SCOTLAND AB41 7NY NatWest CASTLE ROAD ELLON SCOTLAND AB41 9RY Cardtronics UK Ltd ESSLEMONT CIRCLE ELLON SCOTLAND AB41 9UF Barclays LONGSIDE ROAD PETERHEAD SCOTLAND AB42 3JY Cardtronics UK Ltd BRIDGE STREET FRASERBURGH SCOTLAND AB43 6SS NatWest SOUTH HARBOUR ROAD FRASERBURGH SCOTLAND AB43 9TE NoteMachine DUFF STREET MACDUFF SCOTLAND AB44 1PS Cardtronics UK Ltd SEAFIELD STREET BANFF SCOTLAND -

Castle Semple, Lochwinnoch Castle Parkhill Wood Parkhill from “Heartlands” by Betty Mckellar, 1999 NCR7

Mature woodlands, distant views to the Firth of Clyde, a medievalCastle church, Semple, the traces of anLochwinnoch old formal estate, and a loch shore – this route certainly has plenty of variety. In Parkhill Wood you’ll see lots of changes with the passage of the seasons. Bluebells in spring, bright summer flowers, the rich reds and russets of autumn foliage, and bright winter berries attracting feeding birds. Enjoy it at any time of year ! Start and finish Castle Semple Visitor Centre, about 500m from the centre of Lochwinnoch (grid reference NS358590). There are signposts to the Centre in the village, which you can reach by public transport. Distance 8 km (5 miles). Allow 3 hours. Terrain Mixture of excellent flat paths and narrower woodland paths. Some muddy sections. No stiles but The golden finger of a solitary sunbeam shaft some gates. Shows silver silhouettes against the green Of poplar, hawthorn and ash And the slender birch, Ghosts adrift Like grey chiffon Floating in the wisps of twilight Castle Semple, Lochwinnoch Castle Parkhill Wood Parkhill from “Heartlands” by Betty McKellar, 1999 NCR7 5 7 8 3 6 4 9 2 1 Cycle routes N 0 0.2 miles 0 250 metres © Crown copyright. All rights reserved Renfrewshire Council O.S. licence RC100023417 2008. 1 From Castle Semple Visitor Centre car park, walk along the shore of Castle Semple Loch in front of the Centre building. Continue along the shore path. There are plenty of seats along here. 2 At a path junction with a lifebuoy and signboard, turn left up the hill. -

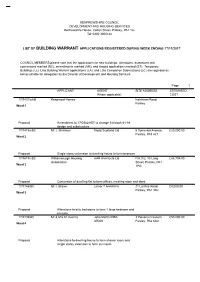

List of Building Warrant Applications Registered During Week Ending 17/11/2017

RENFREWSHIRE COUNCIL DEVELOPMENT AND HOUSING SERVICES Renfrewshire House, Cotton Street, Paisley, PA1 1LL Tel: 0300 3000144 LIST OF BUILDING WARRANT APPLICATIONS REGISTERED DURING WEEK ENDING 17/11/2017 COUNCIL MEMBERS please note that the applications for new buildings, alterations, extensions and conversions marked (BC); amendments marked (AM); and staged applications marked (ST); Temporary Buildings (LL); Late Building Warrant applications (LA); and Late Completion Submissions (LC) are regarded as being suitable for delegation by the Director of Development and Housing Services. Page 1 APPLICANT AGENT SITE ADDRESS ESTIMATED Where applicable) COST 17/1431/eAM Keepmoat Homes Inchinnan Road, Paisley Ward 1 Proposal Amendment to 17/0362/eST to change flat block 61-88 design and substructure 17/1415/eBC Mr J. Shannon Moda Scotland Ltd 8 Somerled Avenue, £20,000.00 Paisley, PA3 4JT Ward 2 Proposal Single storey extension to dwelling house to form bedroom 17/1619/eBC Williamsburgh Housing AHR Architects Ltd Flat 0/2, 10 Lang £43,759.00 Association Street, Paisley, PA1 Ward 3 1PG Proposal Conversion of dwelling flat to form offices, meeting room and store 17/1746/BC Mr J. Brown Linear 7 Architects 21 Lanfine Road, £9,000.00 Paisley, PA1 3NJ Ward 3 Proposal Alterations to attic bedrooms to form 1 large bedroom and en-suite 17/1739/BC Mr & Mrs M. Kearns John Martin RIBA 3 Polsons Crescent, £50,000.00 ARIAS Paisley, PA2 6AU Ward 4 Proposal Alterations to dwelling house to form shower room and single storey extension to form sun room Page 2 APPLICANT AGENT SITE ADDRESS ESTIMATED Where applicable) COST 17/1743/BC Glasgow Airport Limited Administration £1,800.00 Block, Arran Court, Ward 4 St Andrew's Drive, Glasgow Airport, Paisley, PA3 2ST Proposal Alterations to form power supplies for I.T. -

Administration and Divisions

COMMUNICATIONS 1 45 The palmy days of canal traffic both for passengers and goods have passed away. As railways were extended the importance of canals declined. The complete explana- tion of this is by no means easy. It has been attributed to their passing into the control of railway companies, but this explanation is not satisfactory. The smallness of the vessels in use and the consequent additional handling of goods undoubtedly militate against the greater use of canals in these days, when the whole tendency is to handle and carry goods in as large amounts as possible. With the adoption of improved methods of traction or propulsion, there seems no good reason why the importance of canal traffic should not to some extent be restored. 21. Administration and Divisions. Renfrew was originally included with Lanark as an administrative unit, the .separation having been made by King Robert III at the beginning of the fifteenth century. At first the position of sheriff was a hereditary one, and was held by one of the powerful families of the county. The first sheriff that we know of was John Semple of Eliotstoun, who held office in 1426 soon after Renfrew and Lanark were separated. The office remained in the Semple family till it was transferred to the Earl of Eglinton in 1648. Until the Reformation the lands belonging to the Abbey of Paisley were not under the jurisdiction of the sheriff. The abbot was supreme, and had his gallows for hanging men, and his pit for drowning women M. R. 10 146 malefactors. -

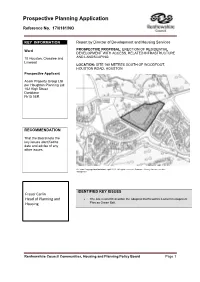

Prospective Planning Application

Prospective Planning Application Reference No. 17/0181/NO KEY INFORMATION Report by Director of Development and Housing Services Ward PROSPECTIVE PROPOSAL: ERECTION OF RESIDENTIAL DEVELOPMENT WITH ACCESS, RELATED INFRASTRUCTURE 10 Houston, Crosslee and AND LANDSCAPING Linwood LOCATION: SITE 160 METRES SOUTH OF WOODFOOT, HOUSTON ROAD, HOUSTON Prospective Applicant Acorn Property Group Ltd per Houghton Planning Ltd 102 High Street Dunblane Fk15 0ER RECOMMENDATION That the Board note the key issues identified to date and advise of any other issues. © Crown Copyright and database right 2013. All rights reserved. Ordnance Survey Licence number 100023417. IDENTIFIED KEY ISSUES Fraser Carlin Head of Planning and The site is identified within the adopted Renfrewshire Local Development Plan as Green Belt. Housing Renfrewshire Council Communities, Housing and Planning Policy Board Page 1 Prospective Application Ref. 17/0181/NO Site Description and justification as to why the site should be Proposal released for housing. The site comprises an area of gently sloping parkland/paddocks forming part of (2) Whether the design, layout, the extensive grounds of Woodend density, form and external finishes respect House, a Category B listed building, and the character of the area; extending to approximately 4.3 hectares, to the east of Houston and north of (3) Whether access and parking, Crosslee/Craigends, and within the Green circulation and other traffic arrangements Belt. are acceptable in terms of road safety and public transport accessibility; The surrounding uses comprise a mix of residential and open countryside and (4) Whether local infrastructure, woodland areas. including sewerage, drainage and educational facilities are capable of It is proposed to develop the site for accommodating the requirements of the residential purposes including open development proposed; and space, landscaping, roads and parking. -

1 Erskine and the Clyde.Indd

There are a few places in and around Glasgow where Start and finish Car park signed “Erskine Riverfront youErskine can walk along and the Clyde.the ErskineClyde is one of the Walkway“ off Kilpatrick Drive, Erskine. The car park is best. It has good footpaths on a long and varied stretch about 150m behind Erskine town centre towards the of the river bank. With luck, you might see a ship: but River Clyde, near Erskine Community Sports Centre (grid don’t bank on it, they are few and far between these reference NS 470708). days. Upstream, the skyline shows off Clydeside’s proud industrial heritage. Downstream, the Kilpatrick Hills loom Distance Just under 6km (4 miles). Allow 2 hours. immediately across the river – and you’ll have the chance to walk under Erskine Bridge. Terrain Mostly flat on wide firm footpaths, either tarmac or gravel. No stiles or gates. Steep section in Boden Boo where boots would be useful. Erskine and the Clyde Erskine Erskine Bridge 7 B 6 B B 5 8 9 1 2 4 3 N 0 0.2 miles 0 250 metres © Crown copyright. All rights reserved Renfrewshire Council O.S. licence RC100023417 2006. 1 From the car park, take the right hand of the two tarmac paths to a semi-circular walk and the Erskine Bridge Hotel, after paved area on the edge of the River Clyde (50m from the start). Then turn right which the path turns away from the river. along the river bank, upstream past the big green navigation light. Erskine… new and old Erskine was a 2 After 500m, the path turns inland at an old harbour. -

GALLOWAY LOCAL GROUP GROUP LEADER’S REPORT Sales Stall So Ably Run, As Usual, by Rhona and Jill

NEWSLETTER 47 AUTUMN 2010 Editor: Stephanie Dewhurst The RSPB speaks out for birds and wildlife, tackling the problems that threaten our environment. Nature is amazing - help us keep it that way. The Royal Society for the Protection of a million Birds (RSPB) is a registered charity: voices for England and Wales No 207076; nature FAIRY TERN IN FLIGHT Scotland Charity No SC037654 GALLOWAY LOCAL GROUP GROUP LEADER’S REPORT sales stall so ably run, as usual, by Rhona and Jill. It was very busy, lots of families there enjoying all the children's Dear Members activities offered by the various organisations and a really As many of you will know my husband Charles passed good atmosphere. Rhona and Jill are still hoping someone th away on 6 July after his cancer suddenly reappeared. (or preferably two) will offer to take over the sales. A contributory factor was the heart failure from which he had suffered since February. He had been the group's Although it had been such a cold winter and spring which newsletter editor for over ten years until the autumn of led us to think that the swallows might be late arriving, 2007. His knowledge of birds and their habitats far in fact, “our birds” arrived on the 19th April, four days exceeded mine which was evident on our walks in the earlier than in many years which just proves you never countryside and on the hills, something denied to him can tell! So far they have had two broods. during the last three years. I hope some of that knowledge has stayed in my memory. -

Information Bulletin June 2018

,1)250$7,21 %8//(7,1 -81( &217(176 6HUYLFH 3DJH1R 'HYHORSPHQW +RXVLQJ6HUYLFHV 'HOHJDWHG,WHPV$SSHDOVDQG%XLOGLQJ:DUUDQWV 0D\WR-XQH (QYLURQPHQWDQG&RPPXQLWLHV 1RWLFHVDQG/LFHQFHV,VVXHG$SULOWR0D\ )LQDQFH 5HVRXUFHV 'HOHJDWHG/LFHQVLQJ$SSOLFDWLRQV0D\DQG-XQH RI RENFREWSHIRE COUNCIL To: INFORMATION BULLETIN By : HEAD OF PLANNING AND DEVELOPMENT Date: June 2018 Subject: DELEGATED ITEMS, APPEALS AND BUILDING WARRANTS 1. SUMMARY 1.1 The undernoted items have been determined by the Director of Development & Housing for Planning Permission under delegated powers. 1.1.1 PLANNING APPLICATIONS Attached as Appendix 1(a) to this report is a list of planning applications dealt with under delegated powers during the period 7 May 2018 to 22 June 2018. Attached as Appendix 1(b) to this report is a list of applications withdrawn under delegated powers during the period 7 May 2018 to 22 June 2018 Attached as Appendix 1(c) to this report is a list of non-material variations dealt with under delegated powers during the period 7 May 2018 to 22 June 2018 Attached as Appendix 1(d) to this report is a list of treeworks applications dealt with under delegated powers during the period7 May 2018 to 22 June 2018. 2. DETERMINATION OF APPEALS 2.1 Attached as Appendix 2 to this report is a list of appeals determined by the Scottish Government Directorate for Planning & Environmental Appeals during the period 7 May 2018 to 22 June 2018 3. APPEALS RECEIVED 3.1 Attached as Appendix 3 to this report is a list of appeals received by the Scottish Government Directorate for Planning & Environmental Appeals during the period 7 May 2018 to 22 June 2018 4. -

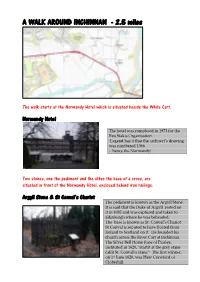

A WALK AROUND INCHINNAN - 2.5 Miles

A WALK AROUND INCHINNAN - 2.5 miles The walk starts at the Normandy Hotel which is situated beside the White Cart. Normandy Hotel The hotel was completed in 1973 for the Reo Stakis Organisation. Legend has it that the architect’s drawing was numbered 1066 - hence the Normandy! Two stones, one the pediment and the other the base of a cross, are situated in front of the Normandy Hotel, enclosed behind iron railings. Argyll Stone & St Conval’s Chariot The pediment is known as the Argyll Stone. It is said that the Duke of Argyll rested on it in 1685 and was captured and taken to Edinburgh where he was beheaded. The base is known as St. Conval’s Chariot. St Conval is reputed to have floated from Ireland to Scotland on it. He founded his church across the River Cart at Inchinnan. The Silver Bell Horse Race of Paisley, instituted in 1620, "startit at the grey stane callit St. Convall's stane." The first winner, on 1st June 1620, was Hew Crawford of Cloberhill. Leaving the Normandy, walk to the river and the bascule bridge. Bascule Bridge The new stone bridge over the White Cart, which was opened in 1812, was too low to accommodate sailing ships as they became larger. This meant that ships sailing up the White Cart to Paisley had to lower their masts to pass through, so a canal was constructed in 1838 to divert ships through a swing bridge. In 1923 this was replaced with the present bascule bridge , built by Sir William Arrol & Company.