MOBILE INTERNET and the RISE of DIGITAL ACTIVISM AMONG UNIVERSITY STUDENTS in NIGERIA Thesis Submitted for the Degree of Doct

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Corruption in Civil Society Activism in the Niger Delta and Defines Csos to Include Ngos, Self-Help Groups and Militant Organisations

THE ROLE OF CORRUPTION ON CIVIL SOCIETY ACTIVISM IN THE NIGER DELTA BY TOMONIDIEOKUMA BRIGHT A THESIS SUBMITTED IN PARTIAL FULFILMENT OF THE REQUIREMENTS OF THE LANCASTER UNIVERSITY FOR DOCTOR OF PHILOSOPHY SUBMISSION DATE: SEPTEMBER, 2019 i Abstract: This thesis studies the challenges and relationships between the Niger delta people, the federal government and Multinational Oil Companies (MNOCs). It describes the major problems caused by unmonitored crude oil exploitation as environmental degradation and underdevelopment. The study highlights the array of roles played by Civil Society Organisations (CSOs) in filling the gap between the stakeholders in the oil industry and crude oil host communities. Except for the contributions from Austin Ikelegbe (2001), Okechukwu Ibeanu (2006) and Shola Omotola (2009), there is a limitation in the literature on corruption and civil society activism in the Niger delta. These authors dwelt on the role of CSOs in the region’s struggle. But this research fills a knowledge gap on the role of corruption in civil society activism in the Niger delta and defines CSOs to include NGOs, self-help groups and militant organisations. Corruption is problematic in Nigeria and affects every sector of the economy including CSOs. The corruption in CSOs is demonstrated in their relationship with MNOCs, the federal government, host communities and donor organisations. Smith (2010) discussed the corruption in NGOs in Nigeria which is also different because this work focuses on the role of corruption in CSOs in the Niger delta and the problems around crude oil exploitation. The findings from the fieldwork using oral history, ethnography, structured and semi-structured interview methods show that corruption impacts CSOs activism in diverse ways and has structural and historical roots embedded in colonialism. -

Zerohack Zer0pwn Youranonnews Yevgeniy Anikin Yes Men

Zerohack Zer0Pwn YourAnonNews Yevgeniy Anikin Yes Men YamaTough Xtreme x-Leader xenu xen0nymous www.oem.com.mx www.nytimes.com/pages/world/asia/index.html www.informador.com.mx www.futuregov.asia www.cronica.com.mx www.asiapacificsecuritymagazine.com Worm Wolfy Withdrawal* WillyFoReal Wikileaks IRC 88.80.16.13/9999 IRC Channel WikiLeaks WiiSpellWhy whitekidney Wells Fargo weed WallRoad w0rmware Vulnerability Vladislav Khorokhorin Visa Inc. Virus Virgin Islands "Viewpointe Archive Services, LLC" Versability Verizon Venezuela Vegas Vatican City USB US Trust US Bankcorp Uruguay Uran0n unusedcrayon United Kingdom UnicormCr3w unfittoprint unelected.org UndisclosedAnon Ukraine UGNazi ua_musti_1905 U.S. Bankcorp TYLER Turkey trosec113 Trojan Horse Trojan Trivette TriCk Tribalzer0 Transnistria transaction Traitor traffic court Tradecraft Trade Secrets "Total System Services, Inc." Topiary Top Secret Tom Stracener TibitXimer Thumb Drive Thomson Reuters TheWikiBoat thepeoplescause the_infecti0n The Unknowns The UnderTaker The Syrian electronic army The Jokerhack Thailand ThaCosmo th3j35t3r testeux1 TEST Telecomix TehWongZ Teddy Bigglesworth TeaMp0isoN TeamHav0k Team Ghost Shell Team Digi7al tdl4 taxes TARP tango down Tampa Tammy Shapiro Taiwan Tabu T0x1c t0wN T.A.R.P. Syrian Electronic Army syndiv Symantec Corporation Switzerland Swingers Club SWIFT Sweden Swan SwaggSec Swagg Security "SunGard Data Systems, Inc." Stuxnet Stringer Streamroller Stole* Sterlok SteelAnne st0rm SQLi Spyware Spying Spydevilz Spy Camera Sposed Spook Spoofing Splendide -

Ethnic Groups in Africa 1 Ethnic Groups in Africa

Ethnic groups in Africa 1 Ethnic groups in Africa Ethnic groups in Africa number in the hundreds, each generally having its own language (or dialect of a language) and culture. Many ethnic groups and nations of Sub-Saharan Africa qualify, although some groups are of a size larger than a tribal society. These mostly originate with the Sahelian kingdoms of the medieval period, such as that of the Igbo of Nigeria, deriving from the Kingdom of Nri (11th century).[1] Overview The following ethnic groups number 10 million people or more: • Arabic, speaking groups: ca. 180 million. See also Ethnic groups of the Middle East • Arab, up to ca. 100 million, see Demographics of the Arab Ethnic groups in Africa in 1996 League • Berber ca. 65 million • Hausa in Nigeria, Niger, Ghana, Chad, Cameroon, Cote d'Ivoire and Sudan (ca. 30 million) • Yoruba in Nigeria and Benin (ca. 30 million) • Oromo in Ethiopia and Kenya (ca. 30 million) • Igbo in Nigeria and Cameroon (ca. 30 million)[2] • Akan in Ghana and Côte d'Ivoire (ca. 20 million) • Amhara in Ethiopia, Sudan, Somalia, Eritrea and Djibouti (ca. 20 million) • Somali in Somalia, Djibouti, Ethiopia and Kenya (ca. 15-17 million) • Ijaw in Nigeria (ca. 14 million) • Kongo in Democratic Republic of the Congo, Angola and Republic of the Congo (ca. 10 million) • Fula in Guinea, Nigeria, Cameroon, Senegal, Mali, Sierra Leone Central African Republic, Burkina Faso, Benin, Niger, Gambia, Guinea Bissau, Ghana, Chad, Sudan, Togo and Côte d'Ivoire (ca. 10 million) • Shona in Zimbabwe and Mozambique (ca. 10 million) • Zulu in South Africa (ca. -

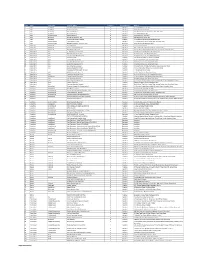

S/No State City/Town Provider Name Category Coverage Type Address

S/No State City/Town Provider Name Category Coverage Type Address 1 Abia AbaNorth John Okorie Memorial Hospital D Medical 12-14, Akabogu Street, Aba 2 Abia AbaNorth Springs Clinic, Aba D Medical 18, Scotland Crescent, Aba 3 Abia AbaSouth Simeone Hospital D Medical 2/4, Abagana Street, Umuocham, Aba, ABia State. 4 Abia AbaNorth Mendel Hospital D Medical 20, TENANT ROAD, ABA. 5 Abia UmuahiaNorth Obioma Hospital D Medical 21, School Road, Umuahia 6 Abia AbaNorth New Era Hospital Ltd, Aba D Medical 212/215 Azikiwe Road, Aba 7 Abia AbaNorth Living Word Mission Hospital D Medical 7, Umuocham Road, off Aba-Owerri Rd. Aba 8 Abia UmuahiaNorth Uche Medicare Clinic D Medical C 25 World Bank Housing Estate,Umuahia,Abia state 9 Abia UmuahiaSouth MEDPLUS LIMITED - Umuahia Abia C Pharmacy Shop 18, Shoprite Mall Abia State. 10 Adamawa YolaNorth Peace Hospital D Medical 2, Luggere Street, Yola 11 Adamawa YolaNorth Da'ama Specialist Hospital D Medical 70/72, Atiku Abubakar Road, Yola, Adamawa State. 12 Adamawa YolaSouth New Boshang Hospital D Medical Ngurore Road, Karewa G.R.A Extension, Jimeta Yola, Adamawa State. 13 Akwa Ibom Uyo St. Athanasius' Hospital,Ltd D Medical 1,Ufeh Street, Fed H/Estate, Abak Road, Uyo. 14 Akwa Ibom Uyo Mfonabasi Medical Centre D Medical 10, Gibbs Street, Uyo, Akwa Ibom State 15 Akwa Ibom Uyo Gateway Clinic And Maternity D Medical 15, Okon Essien Lane, Uyo, Akwa Ibom State. 16 Akwa Ibom Uyo Fulcare Hospital C Medical 15B, Ekpanya Street, Uyo Akwa Ibom State. 17 Akwa Ibom Uyo Unwana Family Hospital D Medical 16, Nkemba Street, Uyo, Akwa Ibom State 18 Akwa Ibom Uyo Good Health Specialist Clinic D Medical 26, Udobio Street, Uyo, Akwa Ibom State. -

Mid-Term Report of the Transformation Agenda

MID-TERM REPORT OF THE TRANSFORMATION AGENDA (MAY 2011 – MAY 2013) TAKING STOCK, MOVING FORWARD 1 LIST OF ACRONYMS AFCON - African Cup of Nations AFN - Armed Forces of Nigeria AG - Associated Gas AGRA - Alliance for Green Revolution in Africa AIS - Aeronautical Information Service AMCON - Asset Management Company of Nigeria APA - Action Push Agenda APC - Amoured Personnel Carriers ASI - All Share Index ASYCUDA - Automated SYstem for CUstoms Data ATA - Agricultural Transformation Agenda ATOs - Aviation Training Organizations AU - African Union AUMTCO - Abuja Urban Mass Transport Company b/d - barrels per day BASAs - Bilateral Air Services Agreements BDC - Bureaux de Change BDS - Business Development Services BoA - Bank of Agric BoI - Bank of Industry BPC - Business Plan Competition BPE - Bureau for Public Enterprises BPP - Bureau of Public Procurement BUDFOW - Business Development Fund for Women CAC - Corporate Affairs Commission CACS - Commercial Agriculture Credit Scheme CAPAM - Commonwealth Association of Public Administration and Management CBN - Central Bank of Nigeria CCTV - Close Circuit Television CDM - Clean Development Mechanism CEDAW - Convention on the Elimination of Discrimination Against Women CEOs - Chief Executive Officers CERS - Coalition Emergency Response Subsystems CHEWs - Community Health Extension Workers CMAM - Community Management of Acute Malnutrition CME/HMF - Coordinating Minister for the Economy/Honourable Minister of Finance CoD - Community of Democracies COPE - Care of People CORS - Continuously Operating -

Bbc Corporate Responsibility Performance Review 2012

BBC CORPORATE RESPONSIBILITY PERFORMANCE REVIEW 2012 For more information see www.bbc.co.uk/outreach 2 Contents Welcome to our latest Corporate Responsibility Performance Review, the last during my time as Director-General. Introduction 3 The BBC’s focus as an international public service broadcaster continues to be on distinctive output, improved value for money, Outreach and the BBC’s Public Purposes 5 doing more to serve all our audiences and being even more open about what we do. Our strategic six-year plan, Delivering Quality Sustainability 13 First, and the long term savings we need to find to live within our means have inevitably meant some tough choices in 2011/12; Our Business 18 however, some things are not negotiable. Supporting Charities 25 BBC licence fee payers expect high quality content across our services; they also expect the BBC to meet the highest standards in Looking Ahead 30 how we behave as an organisation. I believe we are delivering on both of those expectations. In this remarkable year for the UK it has been a source of pride that the work we do beyond broadcasting to benefit our audiences has been so imaginative, collaborative and far-reaching. Cover image: Stargazing Live Oxfordshire, A Stargazing LIVE event at the Rollright Stones, Oxfordshire, organised by Chipping Norton Amateur Astronomy Group attracted around 150 enthusiasts. Mark Thompson Photo: Mel Gigg, CNAAG For more information about other areas of our business, please 3 Introduction see the BBC Annual Report and Accounts the London 2012 Apprenticeships scheme is now building an Olympics legacy in training and careers. -

Harnischfeger Igbo Nationalism & Biafra Long Paper

Igbo Nationalism and Biafra Johannes Harnischfeger, Frankfurt Content 0. Foreword .................................................................... 3 1. Introduction 1.1 The War and its Legacy ....................................... 8 1.2 Trapped in Nigeria.............................................. 13 1.2 Nationalism, Religion, and Global Identities....... 17 2. Patterns of Ethnic and Regional Conflicts 2.1 Early Nationalism ............................................... 23 2.2 The Road to Secession ...................................... 31 3. The Defeat of Biafra 3.1 Left Alone ........................................................... 38 3.2 After the War ...................................................... 44 4. Global Identities and Religion 4.1 9/11 in Nigeria .................................................... 52 4.2 Christian Solidarity ............................................. 59 5. Nationalist Organisations 5.1 Igbo Presidency or Secession............................ 64 2 5.2 Internal Divisions ................................................ 70 6. Defining Igboness 6.1 Reaching for the Stars........................................ 74 6.2 Secular and Religious Nationalism..................... 81 7. A Secular, Afrocentric Vision 7.1 A Community of Suffering .................................. 86 7.2 Roots .................................................................. 91 7.3 Modernism.......................................................... 97 8. The Covenant with God 8.1 In Exile............................................................. -

Bad Habits Asserting Themselves How a Mild Virus Might Turn

Bad Habits Asserting Themselves 3 How a Mild Virus Might Turn Vicious 5 At Last, Facing Down Bullies (and Their Enablers) 7 Is This a Pandemic? Define ‘Pandemic’ 9 Letting the Patient Call the Shots 12 Rotavirus: Every Child Should Be Vaccinated Against Diarrheal Disease, W.H.O. Says 15 1984 thoughtcrime? Does it matter that George Orwell pinched the plot? 16 Diabetes warning signs detected 18 Rogue protein 'spreads in brain' 20 Oily fish 'can halt eye disease' 22 Australia wind farm gets go-ahead 24 Chimps mentally map fruit trees 26 Mobile scanner could detect guns 28 Girls 'hampered by failure fears' 31 Animal Mating Choices More Complex Than Once Thought 33 Hundreds Of Cell-surface Proteins Can Be Simultaneously Studied With New Technique 35 Self-regulation Game Predicts Kindergarten Achievement 38 Prehistoric Complex Including Two 6,000-year-old Tombs Discovered In Britain 39 Fat In Mammalian Cells May Help Explain How Toxin Harms Farm Animals 41 Is Rural Land Use Too Important To Be Left To Farmers? 42 Drinking Water From Air Humidity 43 Cantabrian Cornice Has Experienced Seven Cooling Phases Over Past 41,000 Years 44 Prehistoric Whale Discovered On The West Coast Of Sweden 46 Nanoscale Zipper Cavity Responds To Single Photons Of Light 47 Television Watching Before Bedtime Can Lead To Sleep Debt 50 'Warrior Gene' Linked To Gang Membership, Weapon Use 51 Basket Weaving May Have Taught Humans To Count 53 Archaeologists Locate Confederate Cannons, Naval Yard 55 Flexible Solar Power Shingles Transform Roofs From Wasted Space To Energy -

1 the Influence of Igbo Catechists on Roman

1 THE INFLUENCE OF IGBO CATECHISTS ON ROMAN CATHOLICISM IN IGBOLAND (1888 -1931) BY UMEIKE, RICHARDMARY CHIGBOOGU REG. NO: 2011077019F DEPARTMENT OF RELIGION AND HUMAN RELATIONS, FACULTY OF ARTS NNAMDI AZIKIWE UNIVERSITY, AWKA-NIGERIA MARCH, 2019. 2 THE INFLUENCE OF IGBO CATECHISTS ON ROMAN CATHOLICISM IN IGBOLAND (1888 -1931) BY UMEIKE,RICHARDMARY CHIGBOOGU REG. NO: 2011077019F A DISSERTATION SUBMITTED TO THE DEPARTMENT OF RELIGION AND HUMAN RELATIONS, IN PARTIAL FULFILMENT OF THE REQUIREMENTS FOR THE AWARD OF THEDEGREE OF DOCTOR OF PHILOSOPHY (Ph.D) IN RELIGION AND HUMAN RELATIONS (HISTORY OF CHRISTIANITY) FACULTY OF ARTS NNAMDI AZIKIWE UNIVERSITY, AWKA MARCH, 2019. 3 CERTIFICATION I,Umeike, RichardMary Chigboogu with Registration number 2011077019F, hereby certify that this thesis is original and have been written by me. It is a record of my research and has not been submitted before in part or full for any other diploma or degree of this university or any institution or any previous publications. _____________________________ _________________ Umeike, RichardMary Chigboogu Date (Student) 4 APPROVAL We certify that this dissertation carried out under our supervision, has been examined and found to have met the regulations of Nnamdi Azikiwe University, Awka. We therefore approve the work for the award of Ph.D in Religion and Human Relations (History of Christianity). __________________ ________________ Prof. L.E. Ugwueye Date Supervisor ________________________ ________________ Pro. O.O.C. Uche Date Head of Department ______________________________ _________________ Fr. Prof. Bona Umeogu Date Dean Faculty of Arts ______________________________ _________________ Prof. R.K. Igbokwe Date Dean, School of Post Graduate Studies _______________________________ ________________ External Examiner Date 5 DEDICATION To all Catechists whose inestimable sacrifices watered the seed of Igbo Roman Catholicism. -

Women's Access to Political Power in Ancient Egypt And

WOMEN’S ACCESS TO POLITICAL POWER IN ANCIENT EGYPT AND IGBOLAND: A CRITICAL STUDY A Dissertation Submitted to the Temple University Graduate Board In Partial Fulfillment of the Requirement for the Degree DOCTOR OF PHILOSOPHY by Antwanisha V. Alameen January 2013 Examining Committee Members: Dr. Molefi Kete Asante, Advisory Chair, African American Studies Dr. Ama Mazama, African American Studies Dr. Kimmika Williams-Witherspoon, Theater Dr. Adisa Alkebulan, External Member, San Diego State University i Copyright By Antwanisha Alameen 2012 All Rights Reserved ii ABSTRACT This is an Afrocentric examination of women’s use of agency in Ancient Egypt and Igboland. Most histories written on Kemetic women not only disconnect them from Africa but also fail to fully address the significance of their position within the political spiritual structure of the state. Additionally, the presence of matriarchy in Ancient Egypt is dismissed on the basis that patriarchy is the most visible and seemingly the most dominant form of governance. Diop contended that matriarchy was one of the key factors that connected Ancient Egypt with other parts of Africa which is best understood as the Africa’s cultural continuity theory. My research analyzes the validity of his theory by comparing how Kemetic women exercised agency in their political structure to how Igbo women exercised political agency. I identified Igbo women as a cultural group to be compared to Kemet because of their historical political resistance in their state during the colonial period. However, it is their traditional roles prior to British invasion that is most relevant to my study. I define matriarchy as the central role of the mother in the social and political function of societal structures, the political positions occupied by women that inform the decisions of the state and the inclusion of female principles within the religious-political order of the nation. -

TAKING IT to the STREETS What the New Vox Populi Risk Means for Politics, the Economy and Markets

TAKING IT TO THE STREETS What the New Vox Populi Risk Means for Politics, the Economy and Markets Citi GPS: Global Perspectives & Solutions May 2014 Tina M Fordham Matthew P Dabrowski Willem Buiter Robert Buckland Edward L Morse Citi is one of the world’s largest financial institutions, operating in all major established and emerging markets. Across these world markets, our employees conduct an ongoing multi-disciplinary global conversation – accessing information, analyzing data, developing insights, and formulating advice for our clients. As our premier thought-leadership product, Citi GPS is designed to help our clients navigate the global economy’s most demanding challenges, identify future themes and trends, and help our clients profit in a fast-changing and interconnected world. Citi GPS accesses the best elements of our global conversation and harvests the thought leadership of a wide range of senior professionals across our firm. This is not a research report and does not constitute advice on investments or a solicitation to buy or sell any financial instrument. For more information on Citi GPS, please visit www.citi.com/citigps. Citi GPS: Global Perspectives & Solutions May 2014 Tina M Fordham, Managing Director, is the first and only Chief Global Political Analyst on Wall Street. She has been named in the “Top 100 Most Influential Women in Finance” and the “Top 19 Economists on Wall Street.” With Citi since 2003, she has pioneered a political science-based approach to investment research, specializing in geopolitics and socio-economic risks as well as focusing on more traditional elections and policy analysis. Ms. Fordham is a member of the World Economic Forum’s Geopolitical Risk Committee, Associate Fellow at King's College Graduate Centre Risk Management, and a member of Chatham House and London’s Kit Cat Club. -

Africa Magazine

FOCUS ON MEDIA INFORMATION 2007 AFRICA MAGAZINE Now in its eighteenth successful year, BBC Focus on Africa from across Africa and around the world to its listeners in READERSHIP PROFILE Magazine is published quarterly by the BBC World Service, sub-Saharan Africa. and distributed in virtually every English-speaking country Male 87 Female 13 in Africa. Although it continues to broadcast on short-wave the BBC is becoming increasingly available on FM, making it Aged up to 24 9 Aged 25 to 34 33 The magazine enjoys an excellent reputation as it is seen easier for people across Africa to tune in to its Aged 35 to 44 32 to represent the high quality associated with the BBC programmes. Aged 45 or older 25 No formal/ 2 name. Using a network of correspondents over the primary education continent, it reflects the unbiased, informative and African Heads of State, Ministers and Opposition Leaders Secondary 22 invaluable reporting of the BBC. are frequently interviewed in BBC programmes for Africa Higher 76 in seven different languages. Professional 50 Editorial address Skilled Occupation 21 BBC Focus on Africa magazine Each edition is full of feature articles, news reports and Manual Occupation 5 Bush House Service Occupation 6 photographs covering the continent’s latest political, Student 9 PO Box 76 THE AUDIENCE economic, social, cultural and sporting developments and Other 9 % of Adults (15+) Strand 0 10 20 30 40 50 60 70 80 90 100 London WC2B 4PH providing a unique picture of Africa today. In a typical week, 59.2 million adults listen to the BBC United Kingdom in Africa in any language.