Americana E-Journal of American Studies in Hungary

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

UPA : Redesigning Animation

This document is downloaded from DR‑NTU (https://dr.ntu.edu.sg) Nanyang Technological University, Singapore. UPA : redesigning animation Bottini, Cinzia 2016 Bottini, C. (2016). UPA : redesigning animation. Doctoral thesis, Nanyang Technological University, Singapore. https://hdl.handle.net/10356/69065 https://doi.org/10.32657/10356/69065 Downloaded on 05 Oct 2021 20:18:45 SGT UPA: REDESIGNING ANIMATION CINZIA BOTTINI SCHOOL OF ART, DESIGN AND MEDIA 2016 UPA: REDESIGNING ANIMATION CINZIA BOTTINI School of Art, Design and Media A thesis submitted to the Nanyang Technological University in partial fulfillment of the requirement for the degree of Doctor of Philosophy 2016 “Art does not reproduce the visible; rather, it makes visible.” Paul Klee, “Creative Credo” Acknowledgments When I started my doctoral studies, I could never have imagined what a formative learning experience it would be, both professionally and personally. I owe many people a debt of gratitude for all their help throughout this long journey. I deeply thank my supervisor, Professor Heitor Capuzzo; my cosupervisor, Giannalberto Bendazzi; and Professor Vibeke Sorensen, chair of the School of Art, Design and Media at Nanyang Technological University, Singapore for showing sincere compassion and offering unwavering moral support during a personally difficult stage of this Ph.D. I am also grateful for all their suggestions, critiques and observations that guided me in this research project, as well as their dedication and patience. My gratitude goes to Tee Bosustow, who graciously -

The Disney Strike of 1941: from the Animators' Perspective Lisa Johnson Rhode Island College, Ljohnson [email protected]

Rhode Island College Digital Commons @ RIC Honors Projects Overview Honors Projects 2008 The Disney Strike of 1941: From the Animators' Perspective Lisa Johnson Rhode Island College, [email protected] Follow this and additional works at: https://digitalcommons.ric.edu/honors_projects Part of the Labor Relations Commons, Other Film and Media Studies Commons, Social History Commons, and the United States History Commons Recommended Citation Johnson, Lisa, "The Disney Strike of 1941: From the Animators' Perspective" (2008). Honors Projects Overview. 17. https://digitalcommons.ric.edu/honors_projects/17 This Honors is brought to you for free and open access by the Honors Projects at Digital Commons @ RIC. It has been accepted for inclusion in Honors Projects Overview by an authorized administrator of Digital Commons @ RIC. For more information, please contact [email protected]. The Disney Strike of 1941: From the Animators’ Perspective An Undergraduate Honors Project Presented By Lisa Johnson To The Department of History Approved: Project Advisor Date Chair, Department Honors Committee Date Department Chair Date The Disney Strike of 1941: From the Animators’ Perspective By Lisa Johnson An Honors Project Submitted in Partial Fulfillment of the Requirements for Honors in The Department of History The School of the Arts and Sciences Rhode Island College 2008 1 Table of Contents Introduction Page 3 I. The Strike Page 5 II. The Unheard Struggles for Control: Intellectual Property Rights, Screen Credit, Workplace Environment, and Differing Standards of Excellence Page 17 III. The Historiography Page 42 Afterword Page 56 Bibliography Page 62 2 Introduction On May 28 th , 1941, seventeen artists were escorted out of the Walt Disney Studios in Burbank, California. -

Richard G. Hewlett and Jack M. Holl. Atoms

ATOMS PEACE WAR Eisenhower and the Atomic Energy Commission Richard G. Hewlett and lack M. Roll With a Foreword by Richard S. Kirkendall and an Essay on Sources by Roger M. Anders University of California Press Berkeley Los Angeles London Published 1989 by the University of California Press Berkeley and Los Angeles, California University of California Press, Ltd. London, England Prepared by the Atomic Energy Commission; work made for hire. Library of Congress Cataloging-in-Publication Data Hewlett, Richard G. Atoms for peace and war, 1953-1961. (California studies in the history of science) Bibliography: p. Includes index. 1. Nuclear energy—United States—History. 2. U.S. Atomic Energy Commission—History. 3. Eisenhower, Dwight D. (Dwight David), 1890-1969. 4. United States—Politics and government-1953-1961. I. Holl, Jack M. II. Title. III. Series. QC792. 7. H48 1989 333.79'24'0973 88-29578 ISBN 0-520-06018-0 (alk. paper) Printed in the United States of America 1 2 3 4 5 6 7 8 9 CONTENTS List of Illustrations vii List of Figures and Tables ix Foreword by Richard S. Kirkendall xi Preface xix Acknowledgements xxvii 1. A Secret Mission 1 2. The Eisenhower Imprint 17 3. The President and the Bomb 34 4. The Oppenheimer Case 73 5. The Political Arena 113 6. Nuclear Weapons: A New Reality 144 7. Nuclear Power for the Marketplace 183 8. Atoms for Peace: Building American Policy 209 9. Pursuit of the Peaceful Atom 238 10. The Seeds of Anxiety 271 11. Safeguards, EURATOM, and the International Agency 305 12. -

Digital Surrealism: Visualizing Walt Disney Animation Studios

City University of New York (CUNY) CUNY Academic Works Publications and Research Queens College 2017 Digital Surrealism: Visualizing Walt Disney Animation Studios Kevin L. Ferguson CUNY Queens College How does access to this work benefit ou?y Let us know! More information about this work at: https://academicworks.cuny.edu/qc_pubs/205 Discover additional works at: https://academicworks.cuny.edu This work is made publicly available by the City University of New York (CUNY). Contact: [email protected] 1 Digital Surrealism: Visualizing Walt Disney Animation Studios Abstract There are a number of fruitful digital humanities approaches to cinema and media studies, but most of them only pursue traditional forms of scholarship by extracting a single variable from the audiovisual text that is already legible to scholars. Instead, cinema and media studies should pursue a mostly-ignored “digital-surrealism” that uses computer-based methods to transform film texts in radical ways not previously possible. This article describes one such method using the z-projection function of the scientific image analysis software ImageJ to sum film frames in order to create new composite images. Working with the fifty-four feature-length films from Walt Disney Animation Studios, I describe how this method allows for a unique understanding of a film corpus not otherwise available to cinema and media studies scholars. “Technique is the very being of all creation” — Roland Barthes “We dig up diamonds by the score, a thousand rubies, sometimes more, but we don't know what we dig them for” — The Seven Dwarfs There are quite a number of fruitful digital humanities approaches to cinema and media studies, which vary widely from aesthetic techniques of visualizing color and form in shots to data-driven metrics approaches analyzing editing patterns. -

The University of Chicago Looking at Cartoons

THE UNIVERSITY OF CHICAGO LOOKING AT CARTOONS: THE ART, LABOR, AND TECHNOLOGY OF AMERICAN CEL ANIMATION A DISSERTATION SUBMITTED TO THE FACULTY OF THE DIVISION OF THE HUMANITIES IN CANDIDACY FOR THE DEGREE OF DOCTOR OF PHILOSOPHY DEPARTMENT OF CINEMA AND MEDIA STUDIES BY HANNAH MAITLAND FRANK CHICAGO, ILLINOIS AUGUST 2016 FOR MY FAMILY IN MEMORY OF MY FATHER Apparently he had examined them patiently picture by picture and imagined that they would be screened in the same way, failing at that time to grasp the principle of the cinematograph. —Flann O’Brien CONTENTS LIST OF FIGURES...............................................................................................................................v ABSTRACT.......................................................................................................................................vii ACKNOWLEDGMENTS....................................................................................................................viii INTRODUCTION LOOKING AT LABOR......................................................................................1 CHAPTER 1 ANIMATION AND MONTAGE; or, Photographic Records of Documents...................................................22 CHAPTER 2 A VIEW OF THE WORLD Toward a Photographic Theory of Cel Animation ...................................72 CHAPTER 3 PARS PRO TOTO Character Animation and the Work of the Anonymous Artist................121 CHAPTER 4 THE MULTIPLICATION OF TRACES Xerographic Reproduction and One Hundred and One Dalmatians.......174 -

Animated Stereotypes –

Animated Stereotypes – An Analysis of Disney’s Contemporary Portrayals of Race and Ethnicity Alexander Lindgren, 36761 Pro gradu-avhandling i engelska språket och litteraturen Handledare: Jason Finch Fakulteten för humaniora, psykologi och teologi Åbo Akademi 2020 ÅBO AKADEMI – FACULTY OF ARTS, PSYCHOLOGY AND THEOLOGY Abstract for Master’s Thesis Subject: English Language and Literature Author: Alexander Lindgren Title: Animated Stereotypes – An Analysis of Disney’s Contemporary Portrayals of Race and Ethnicity Supervisor: Jason Finch Abstract: Walt Disney Animation Studios is currently one of the world’s largest producers of animated content aimed at children. However, while Disney often has been associated with themes such as childhood, magic, and innocence, many of the company’s animated films have simultaneously been criticized for their offensive and quite problematic take on race and ethnicity, as well their heavy reliance on cultural stereotypes. This study aims to evaluate Disney’s portrayals of racial and ethnic minorities, as well as determine whether or not the nature of the company’s portrayals have become more culturally sensitive with time. To accomplish this, seven animated feature films produced by Disney were analyzed. These analyses are of a qualitative nature, with a focus on imagology and postcolonial literary theory, and the results have simultaneously been compared to corresponding criticism and analyses by other authors and scholars. Based on the overall results of the analyses, it does seem as if Disney is becoming more progressive and culturally sensitive with time. However, while most of the recent films are free from the clearly racist elements found in the company’s earlier productions, it is quite evident that Disney still tends to rely heavily on certain cultural stereotypes. -

Lister); an American Folk Rhapsody Deutschmeister Kapelle/JULIUS HERRMANN; Band of the Welsh Guards/Cap

Guild GmbH Guild -Light Catalogue Bärenholzstrasse 8, 8537 Nussbaumen, Switzerland Tel: +41 52 742 85 00 - e-mail: [email protected] CD-No. Title Track/Composer Artists GLCD 5101 An Introduction Gateway To The West (Farnon); Going For A Ride (Torch); With A Song In My Heart QUEEN'S HALL LIGHT ORCHESTRA/ROBERT FARNON; SIDNEY TORCH AND (Rodgers, Hart); Heykens' Serenade (Heykens, arr. Goodwin); Martinique (Warren); HIS ORCHESTRA; ANDRE KOSTELANETZ & HIS ORCHESTRA; RON GOODWIN Skyscraper Fantasy (Phillips); Dance Of The Spanish Onion (Rose); Out Of This & HIS ORCHESTRA; RAY MARTIN & HIS ORCHESTRA; CHARLES WILLIAMS & World - theme from the film (Arlen, Mercer); Paris To Piccadilly (Busby, Hurran); HIS CONCERT ORCHESTRA; DAVID ROSE & HIS ORCHESTRA; MANTOVANI & Festive Days (Ancliffe); Ha'penny Breeze - theme from the film (Green); Tropical HIS ORCHESTRA; L'ORCHESTRE DEVEREAUX/GEORGES DEVEREAUX; (Gould); Puffin' Billy (White); First Rhapsody (Melachrino); Fantasie Impromptu in C LONDON PROMENADE ORCHESTRA/ WALTER COLLINS; PHILIP GREEN & HIS Sharp Minor (Chopin, arr. Farnon); London Bridge March (Coates); Mock Turtles ORCHESTRA; MORTON GOULD & HIS ORCHESTRA; DANISH STATE RADIO (Morley); To A Wild Rose (MacDowell, arr. Peter Yorke); Plink, Plank, Plunk! ORCHESTRA/HUBERT CLIFFORD; MELACHRINO ORCHESTRA/GEORGE (Anderson); Jamaican Rhumba (Benjamin, arr. Percy Faith); Vision in Velvet MELACHRINO; KINGSWAY SO/CAMARATA; NEW LIGHT SYMPHONY (Duncan); Grand Canyon (van der Linden); Dancing Princess (Hart, Layman, arr. ORCHESTRA/JOSEPH LEWIS; QUEEN'S HALL LIGHT ORCHESTRA/ROBERT Young); Dainty Lady (Peter); Bandstand ('Frescoes' Suite) (Haydn Wood) FARNON; PETER YORKE & HIS CONCERT ORCHESTRA; LEROY ANDERSON & HIS 'POPS' CONCERT ORCHESTRA; PERCY FAITH & HIS ORCHESTRA; NEW CONCERT ORCHESTRA/JACK LEON; DOLF VAN DER LINDEN & HIS METROPOLE ORCHESTRA; FRANK CHACKSFIELD & HIS ORCHESTRA; REGINALD KING & HIS LIGHT ORCHESTRA; NEW CONCERT ORCHESTRA/SERGE KRISH GLCD 5102 1940's Music In The Air (Lloyd, arr. -

Unsung Sherman Brothers

Unsung Sherman Brothers y the late 1960s, the songwriting team THE 13 CLOCKS ■ ■ ■ ■ ■ imation process is, and they could not raise the known as the Sherman Brothers was al- money to continue. And so, the second project Bready legendary thanks to Mary Poppins, In 1950, the great cartoonist/humorist James was cancelled. The Jungle Book, and any number of other Dis- Thurber published his fantasy story, The 13 ney classics, not to mention their Disneyland an- Clocks, a tale about a prince who must perform Again, thankfully, a demo recording was made, them, “It’s a Small World.” And, of course, there a seemingly impossible task, to rescue a maiden with several of the voice actors singing their was Chitty, Chitty, Bang, Bang, with its fantastical from an evil duke. Thurber, who by then was songs, including Sammy Davis, Jr., Karl Malden, song score. So, it’s hard to imagine that in 1969 blind, could not do the drawings for the book, so and Jinny Tyler. And again, the brothers’ songs three exciting new Sherman Brothers projects he turned to a friend, Marc Simont. The book has are toe-tapping tuneful wonders – from the kicky were all cancelled, back to back, one after an- been in print ever since, and read by thousands “Sir Puss-in-Boots” to the great “Rhythm of the other. And these projects were heartbreakers for of happy readers all over the world. In 1968, Road” (we also include a more “Sammyized” ver- “the boys” (as Walt Disney called them), three Warner Bros. hired producer Mervyn LeRoy sion of that, which is simply supercalifragilisticex- that got away. -

Glorious Technicolor: from George Eastman House and Beyond Screening Schedule June 5–August 5, 2015 Friday, June 5 4:30 the G

Glorious Technicolor: From George Eastman House and Beyond Screening Schedule June 5–August 5, 2015 Friday, June 5 4:30 The Garden of Allah. 1936. USA. Directed by Richard Boleslawski. Screenplay by W.P. Lipscomb, Lynn Riggs, based on the novel by Robert Hichens. With Marlene Dietrich, Charles Boyer, Basil Rathbone, Joseph Schildkraut. 35mm restoration by The Museum of Modern Art, with support from the Celeste Bartos Fund for Film Preservation; courtesy The Walt Disney Studios. 75 min. La Cucaracha. 1934. Directed by Lloyd Corrigan. With Steffi Duna, Don Alvarado, Paul Porcasi, Eduardo Durant’s Rhumba Band. Courtesy George Eastman House (35mm dye-transfer print on June 5); and UCLA Film & Television Archive (restored 35mm print on July 21). 20 min. [John Barrymore Technicolor Test for Hamlet]. 1933. USA. Pioneer Pictures. 35mm print from The Museum of Modern Art. 5 min. 7:00 The Wizard of Oz. 1939. USA. Directed by Victor Fleming. Screenplay by Noel Langley, Florence Ryerson, Edgar Allan Woolf, based on the book by L. Frank Baum. Music by Harold Arlen, E.Y. Harburg. With Judy Garland, Frank Morgan, Ray Bolger, Bert Lahr, Ray Bolger, Margaret Hamilton, Billie Burke. 35mm print from George Eastman House; courtesy Warner Bros. 102 min. Saturday, June 6 2:30 THE DAWN OF TECHNICOLOR: THE SILENT ERA *Special Guest Appearances: James Layton and David Pierce, authors of The Dawn of Technicolor, 1915-1935 (George Eastman House, 2015). James Layton and David Pierce illustrate Technicolor’s origins during the silent film era. Before Technicolor achieved success in the 1930s, the company had to overcome countless technical challenges and persuade cost-conscious producers that color was worth the extra effort and expense. -

The Summer Lobo, Volume 009, No 2, 6/16/1939

University of New Mexico UNM Digital Repository 1938 The aiD ly Lobo 1931 - 1940 6-16-1938 The ummeS r Lobo, Volume 009, No 2, 6/16/1939 University of New Mexico Follow this and additional works at: https://digitalrepository.unm.edu/daily_lobo_1938 Recommended Citation University of New Mexico. "The ummeS r Lobo, Volume 009, No 2, 6/16/1939." 9, 2 (1938). https://digitalrepository.unm.edu/ daily_lobo_1938/35 This Newspaper is brought to you for free and open access by the The aiD ly Lobo 1931 - 1940 at UNM Digital Repository. It has been accepted for inclusion in 1938 by an authorized administrator of UNM Digital Repository. For more information, please contact [email protected]. e Four THE SUMMER LOBO Tuesday, June 6, 1939 liant :McLeish Dunbar, who has been organize the art department of tmmer Students Ready Dean St. Clair a professor of architecture at Scrip;ps College, California, during Cornell University ;for the past 15 which time he headed the a:rt de" T~~ SUMM~R ~LOBO o Study Hard or Hardly Study Congratulates years. partment there. Dunbar is a fellow in the Ameri- UNIVERSITY OF NEW MEXICO By Paul Kircher Publications Board can Institute of Architecture, ln Cricket, the famed English Edited and P~:~blished by the Journalism Class hum-summ.er school starts, FASHION PREVIEW 1931 he was granted .a four years' game, is a popular student sport re is a lot of hard work, while * * Health Improved; leave of absence :from Cornell to at Mount Angel College. VoL. IX ALBUQUERQUE, NEW MEXICO, FRIDAY, JUNE 16, 1939 No.2 •b(ldy else is loafing around in Fights Philistines at the seashore, or the world~s . -

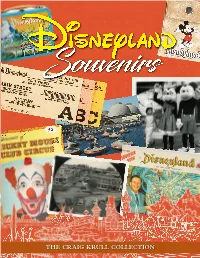

The Craig Krull Collection the Craig Krull Collection

Disneyland COVER THE CRAIG KRULL COLLECTION THE CRAIG KRULL COLLECTION FRIDAY JUNE 9, 2017 IMMEDIATELY FOLLOWING LOT 611 OF ANIMATION & DISNEYANA AUCTION 94 LIVE • MAIL • PHONE • FAX • INTERNET Place your bid over the Internet! PROFILES IN HISTORY will be providing Internet-based bidding to qualified bidders in real-time on the day of the auction. For more information visit us @ www.profilesinhistory.com CATALOG PRICE AUCTION LOCATION (PREVIEWS BY APPOINTMENT ONLY) $35.00 PROFILES IN HISTORY, 26662 AGOURA ROAD, CALABASAS, CA 91302 CALL: 310-859-7701 FAX: 310-859-3842 This auction is a continuation of Profiles in History’s Animation & Disneyana Auction 94, which begins at 11 am PDT on June 9th, 2017, and will commence immediately following Lot 611 of Auction 94. Bidders may register by phone, online at www.profilesinhistory.com, or use the registration and bidding forms in the Auction 94 catalog. “CONDITIONS OF SALE” Profiles may accept current and valid VISA, MasterCard, Discover removed from the premises or possession transferred to Buyer unless and American Express credit or debit cards for payment but under Buyer has fully complied with these Conditions of Sale and the terms AGREEMENT BETWEEN PROFILES IN HISTORY AND the express condition that any property purchased by credit or debit of the Registration Form, and unless and until Profiles has received BIDDER. BY EITHER REGISTERING TO BID OR PLACING A card shall not be refundable, returnable, or exchangeable, and that no the Purchase Price funds in full. Notwithstanding the above, all BID, THE BIDDER ACCEPTS THESE CONDITIONS OF SALE credit to Buyer’s credit or debit card account will be issued under any property must be removed from the premises by Buyer at his or her AND ENTERS INTO A LEGALLY, BINDING, ENFORCEABLE circumstances. -

The Mickey Mouse Sex Tapes (A Fan Fiction Screenplay) by Dawn Bloothe [email protected] Copyright (C) 2019 This Screenplay

The Mickey Mouse Sex Tapes (a Fan Fiction Screenplay) by Dawn Bloothe [email protected] Copyright (c) 2019 This screenplay may not be used or reproduced for any purpose including educational purposes without the expressed written permission of the author. 1 NOTE: This film is a combination of live action and animation. There are all-cartoon sequences that take place in Toontown, as well as toons who come out into a live action world, in the manner of the film “Who Framed Roger Rabbit?” FADE IN: EXT. TOONTOWN STREET – NIGHT Toontown is the cartoon suburb of Los Angeles where toons (cartoon characters) live. The street is lined with suburban houses. It is raining hard. / car races down the street at high speed. It is driven by an exasperated MICKEY MOUSE. IN THE CAR MICKEY MOUSE (muttering to himself) It can’t be. It just can’t be. I can’t believe it. MICKEY’S POV A road sign reads “Suburb of Duckburg - Exit 1 mile ahead” OUTSIDE The car takes the Suburb of Duckburg exit. EXT. DONALD DUCK’S HOUSE – NIGHT Mickey Mouse drives his car up to the front and stops. He gets out and runs up to the house. He POUNDS on the door. INT. LIVINGROOM – DAY DONALD DUCK is watching TV. There are SOUNDS of an old western playing. Donald Duck hears the pounding on his front door. 2 DONALD DUCK (irritated) What the...? Donald Duck gets up and heads for the door. DONALD DUCK (calling, irritated) Hold onto your horses, jackass! (muttering to himself) Break the door down, why doncha? Donald Duck angrily opens the door, REVEALING a very distraught- looking Mickey Mouse.