Download Download

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

The Taxonomic Challenge Posed by the Antarctic Echinoids Abatus Bidens and Abatus Cavernosus (Schizasteridae, Echinoidea)

Polar Biol DOI 10.1007/s00300-015-1842-5 ORIGINAL PAPER The taxonomic challenge posed by the Antarctic echinoids Abatus bidens and Abatus cavernosus (Schizasteridae, Echinoidea) 1,4 1 2 Bruno David • Thomas Sauce`de • Anne Chenuil • 1 3 Emilie Steimetz • Chantal De Ridder Received: 31 August 2015 / Revised: 6 November 2015 / Accepted: 16 November 2015 Ó Springer-Verlag Berlin Heidelberg 2015 Abstract Cryptic species have been repeatedly described together in two haplogroups separated from one another by for two decades among the Antarctic fauna, challenging the 2.7 % of nucleotide differences. They are located in the classic model of Antarctic species with circumpolar dis- Weddell Sea and in the Bransfield Strait. Specimens of A. tributions and leading to revisit the richness of the cavernosus form one single haplogroup separated from Antarctic fauna. No cryptic species had been so far haplogroups of A. bidens by 5 and 3.5 % of nucleotide recorded among Antarctic echinoids, which are, however, differences, respectively. The species was collected in the relatively well diversified in the Southern Ocean. The R/V Drake Passage and in the Bransfield Strait. Morphological Polarstern cruise PS81 (ANT XXIX/3) came across pop- analyses differentiate A. bidens from A. cavernosus. In ulations of Abatus bidens, a schizasterid so far known by contrast, the two genetic groups of A. bidens cannot be few specimens that were found living in sympatry with the differentiated from one another based on morphology species Abatus cavernosus. The species A. cavernosus is alone, suggesting that they may represent a case of cryptic reported to have a circum-Antarctic distribution, while A. -

SI Appendix for Hopkins, Melanie J, and Smith, Andrew B

Hopkins and Smith, SI Appendix SI Appendix for Hopkins, Melanie J, and Smith, Andrew B. Dynamic evolutionary change in post-Paleozoic echinoids and the importance of scale when interpreting changes in rates of evolution. Corrections to character matrix Before running any analyses, we corrected a few errors in the published character matrix of Kroh and Smith (1). Specifically, we removed the three duplicate records of Oligopygus, Haimea, and Conoclypus, and removed characters C51 and C59, which had been excluded from the phylogenetic analysis but mistakenly remain in the matrix that was published in Appendix 2 of (1). We also excluded Anisocidaris, Paurocidaris, Pseudocidaris, Glyphopneustes, Enichaster, and Tiarechinus from the character matrix because these taxa were excluded from the strict consensus tree (1). This left 164 taxa and 303 characters for calculations of rates of evolution and for the principal coordinates analysis. Other tree scaling methods The most basic method for scaling a tree using first appearances of taxa is to make each internal node the age of its oldest descendent ("stand") (2), but this often results in many zero-length branches which are both theoretically questionable and in some cases methodologically problematic (3). Several methods exist for modifying zero-length branches. In the case of the results shown in Figure 1, we assigned a positive length to each zero-length branch by having it share time equally with a preceding, non-zero-length branch (“equal”) (4). However, we compared the results from this method of scaling to several other methods. First, we compared this with rates estimated from trees scaled such that zero-length branches share time proportionally to the amount of character change along the branches (“prop”) (5), a variation which gave almost identical results as the method used for the “equal” method (Fig. -

Spatangus Purpureus O.F. Müller, 1776

Spatangus purpureus O.F. Müller, 1776 AphiaID: 124418 VIOLET HEART-URCHIN Animalia (Reino) > Echinodermata (Filo) > Echinozoa (Subfilo) > Echinoidea (Classe) > Euechinoidea (Subclasse) > Irregularia (Infraclasse) > Atelostomata (Superordem) > Spatangoida (Ordem) > Brissidina (Subordem) > Spatangoidea (Superfamilia) > Spatangidae (Familia) © Vasco Ferreira Hans Hillewaert Roberto Pillon Facilmente confundível com: 1 Echinocardium cordatum Ouriço-coração Sinónimos Prospatangus purpureus (O.F. Müller, 1776) Spatagus purpureus O.F. Müller, 1776 Spatangus meridionalis Risso, 1825 Spatangus Regina Spatangus reginae Gray, 1851 Spatangus spinosissimus Desor in L. Agassiz & Desor, 1847b Referências additional source Hansson, H. (2004). North East Atlantic Taxa (NEAT): Nematoda. Internet pdf Ed. Aug 1998., available online at http://www.tmbl.gu.se/libdb/taxon/taxa.html [details] basis of record Hansson, H.G. (2001). Echinodermata, in: Costello, M.J. et al. (Ed.) (2001). European register of marine species: a check-list of the marine species in Europe and a bibliography of guides to their identification. Collection Patrimoines Naturels,. 50: pp. 336-351. [details] additional source Southward, E.C.; Campbell, A.C. (2006). [Echinoderms: keys and notes for the identification of British species]. Synopses of the British fauna (new series), 56. Field Studies Council: Shrewsbury, UK. ISBN 1-85153-269-2. 272 pp. [details] additional source Muller, Y. (2004). Faune et flore du littoral du Nord, du Pas-de-Calais et de la Belgique: inventaire. [Coastal fauna and flora of the Nord, Pas-de-Calais and Belgium: inventory]. Commission Régionale de Biologie Région Nord Pas-de-Calais: France. 307 pp., available online at http://www.vliz.be/imisdocs/publications/145561.pdf [details] original description Müller, O. F. (1776). Zoologiae Danicae prodromus: seu Animalium Daniae et Norvegiae indigenarum characteres, nomina, et synonyma imprimis popularium. -

Programa Fondecyt Informe Final Etapa 2011 Comisión

PROGRAMA FONDECYT INFORME FINAL ETAPA 2011 COMISIÓN NACIONAL DE INVESTIGACION CIENTÍFICA Y TECNOLÓGICA VERSION OFICIAL Nº 2 FECHA: 28/06/2013 Nº PROYECTO : 3100139 DURACIÓN : 2 años AÑO ETAPA : 2011 TÍTULO PROYECTO : GENETIC DIVERSITY AND SMALL SCALE POPULATION STRUCTURE OF ABATUS AGASSIZII (MORTENSEN, 1910), A BROODING ANTARCTIC ECHINOID FROM BAHIA FILDES, KING GEORGES ISLAND, SOUTH SHETLAND. DISCIPLINA PRINCIPAL : GENETICA Y EVOLUCION GRUPO DE ESTUDIO : BIOLOGIA 1 INVESTIGADOR(A) RESPONSABLE : KARIN FRANÇOISE GERARD CIUDAD : Santiago REGIÓN : METROPOLITANA FONDO NACIONAL DE DESARROLLO CIENTIFICO Y TECNOLOGICO (FONDECYT) Moneda 1375, Santiago de Chile - casilla 297-V, Santiago 21 Telefono: 2435 4350 FAX 2365 4435 Email: [email protected] INFORME FINAL PROYECTO FONDECYT POSTDOCTORADO OBJETIVOS Cumplimiento de los Objetivos planteados en la etapa final, o pendientes de cumplir. Recuerde que en esta sección debe referirse a objetivos desarrollados, NO listar actividades desarrolladas. Nº OBJETIVOS CUMPLIMIENTO FUNDAMENTO 1 Delimitación geográfica de la población y TOTAL Al principio del proyecto, se conocía un solo sitio obtención de muestras de Abatus agassizii en de con Abatus agassizii se en la Caleta Ardley Bahía Fildes (Bahía Fildes). En la campaña de terreno 2010 en Antártica, buscamos erizos en la Caleta Ardley y frente al glaciar Collins. En 2011, la búsqueda cubro el resto de la Bahía Fildes: la caleta de la Base China, la zona de la base Coreana y la costa Suroeste de la Bahía Fildes. Tuvimos la oportunidad de buscar en la Bahía Almirantazgo y cerca de la Isla Ross (Sur del Paso Antártico). De eso, resulto un mapa de presencia/Ausencia de A. agassizii (ver resultados parte 1). -

Big Oyster, Robust Echinoid: an Unusual Association from the Maastrichtian Type Area (Province of Limburg, Southern Netherlands)

Swiss Journal of Palaeontology (2018) 137:357–361 https://doi.org/10.1007/s13358-018-0151-3 (0123456789().,-volV)(0123456789().,-volV) REGULAR RESEARCH ARTICLE Big oyster, robust echinoid: an unusual association from the Maastrichtian type area (province of Limburg, southern Netherlands) 1,2 3 Stephen K. Donovan • John W. M. Jagt Received: 27 February 2018 / Accepted: 10 May 2018 / Published online: 1 June 2018 Ó Akademie der Naturwissenschaften Schweiz (SCNAT) 2018 Abstract Large, denuded tests of holasteroid echinoids were robust benthic islands in the Late Cretaceous seas of northwest Europe. A test of Hemipneustes striatoradiatus (Leske) from the Nekum Member (Maastricht Formation; upper Maastrichtian) of southern Limburg, the Netherlands, is encrusted by a large oyster, Pycnodonte (Phygraea) vesiculare (Lamarck). This specimen is a palaeoecological conundrum, at least in part. No other members of the same oyster spatfall attached to this test and survived. Indeed, only two other, much smaller bivalve shells, assignable to the same species, attached either then or somewhat later. The oyster, although large, could have grown to this size in a single season. The larval oyster cemented high on the test and this would have been advantageous initially, the young shell being elevated above sediment-laden bottom waters. However, as the oyster grew, the incurrent margin of the commissure would have grown closer to the sediment surface. Thus, the quality of the incurrent water probably deteriorated with time. Keywords Late Cretaceous Á Pycnodonte Á Hemipneustes Á Taphonomy Á Palaeoecology Introduction et al. 2013, 2017). Associations on holasteroid tests may be monospecific or nearly so, such as dense accumulations of Large holasteroid echinoids, such as the genera pits assigned to Oichnus Bromley, 1981 (see, for example, Echinocorys Leske, 1778, Cardiaster Forbes, 1850, and Donovan and Jagt 2002; Hammond and Donovan 2017; Hemipneustes Agassiz, 1836, in the Upper Cretaceous of Donovan et al. -

Benthic Habitat Classes and Trawl Fishing Disturbance in New Zealand Waters Shallower Than 250 M

Benthic habitat classes and trawl fishing disturbance in New Zealand waters shallower than 250 m New Zealand Aquatic Environment and Biodiversity Report No.144 S.J. Baird, J. Hewitt, B.A. Wood ISSN 1179-6480 (online) ISBN 978-0-477-10532-3 (online) January 2015 Requests for further copies should be directed to: Publications Logistics Officer Ministry for Primary Industries PO Box 2526 WELLINGTON 6140 Email: [email protected] Telephone: 0800 00 83 33 Facsimile: 04-894 0300 This publication is also available on the Ministry for Primary Industries websites at: http://www.mpi.govt.nz/news-resources/publications.aspx http://fs.fish.govt.nz go to Document library/Research reports © Crown Copyright - Ministry for Primary Industries Contents EXECUTIVE SUMMARY 1 1. INTRODUCTION 3 The study area 3 2. COASTAL BENTHIC HABITAT CLASSES 4 2.1 Introduction 4 2.2 Habitat class definitions 6 2.3 Sensitivity of the habitat to fishing disturbance 10 3. SPATIAL PATTERN OF BOTTOM-CONTACTING TRAWL FISHING ACTIVITY 11 3.1 Bottom-contact trawl data 12 3.2 Spatial distribution of trawl data 21 3.3 Trawl footprint within the study area 26 3.4 Overlap of five-year trawl footprint on habitats within 250 m 32 3.5 GIS output from the overlay of the trawl footprint and habitat classes 37 4. SUMMARY OF NON-TRAWL BOTTOM-CONTACT FISHING METHODS IN THE STUDY AREA 38 5. DISCUSSION 39 6. ACKNOWLEDGMENTS 41 7. REFERENCES 42 APPENDIX 1: AREAS CLOSED TO FISHING WITHIN THE STUDY AREA 46 APPENDIX 2: MAPS SHOWING THE DISTRIBUTION OF THE DATA INPUTS FOR THE BENTHIC HABITAT DESCRIPTORS 49 APPENDIX 3: SENSITIVITY TO FISHING DISTURBANCE 53 APPENDIX 4: TRAWL FISHING DATA 102 APPENDIX 5: CELL-BASED TRAWL SUMMARIES 129 APPENDIX 6: TRAWL FOOTPRINT SUMMARY 151 APPENDIX 7: TRAWL FOOTPRINT – HABITAT OVERLAY 162 APPENDIX 8: SUMMARY OF DREDGE OYSTER AND SCALLOP EFFORT DATA WITHIN 250 M, 1 OCTOBER 2007–30 SEPTEMBER 2012 165 APPENDIX 9: SUMMARY OF DANISH SEINE EFFORT 181 EXECUTIVE SUMMARY Baird, S.J.; Hewitt, J.E.; Wood, B.A. -

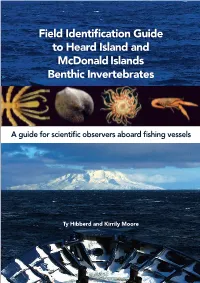

Benthic Field Guide 5.5.Indb

Field Identifi cation Guide to Heard Island and McDonald Islands Benthic Invertebrates Invertebrates Benthic Moore Islands Kirrily and McDonald and Hibberd Ty Island Heard to Guide cation Identifi Field Field Identifi cation Guide to Heard Island and McDonald Islands Benthic Invertebrates A guide for scientifi c observers aboard fi shing vessels Little is known about the deep sea benthic invertebrate diversity in the territory of Heard Island and McDonald Islands (HIMI). In an initiative to help further our understanding, invertebrate surveys over the past seven years have now revealed more than 500 species, many of which are endemic. This is an essential reference guide to these species. Illustrated with hundreds of representative photographs, it includes brief narratives on the biology and ecology of the major taxonomic groups and characteristic features of common species. It is primarily aimed at scientifi c observers, and is intended to be used as both a training tool prior to deployment at-sea, and for use in making accurate identifi cations of invertebrate by catch when operating in the HIMI region. Many of the featured organisms are also found throughout the Indian sector of the Southern Ocean, the guide therefore having national appeal. Ty Hibberd and Kirrily Moore Australian Antarctic Division Fisheries Research and Development Corporation covers2.indd 113 11/8/09 2:55:44 PM Author: Hibberd, Ty. Title: Field identification guide to Heard Island and McDonald Islands benthic invertebrates : a guide for scientific observers aboard fishing vessels / Ty Hibberd, Kirrily Moore. Edition: 1st ed. ISBN: 9781876934156 (pbk.) Notes: Bibliography. Subjects: Benthic animals—Heard Island (Heard and McDonald Islands)--Identification. -

Microbial Composition and Genes for Key Metabolic Attributes in the Gut

Article Microbial Composition and Genes for Key Metabolic Attributes in the Gut Digesta of Sea Urchins Lytechinus variegatus and Strongylocentrotus purpuratus Using Shotgun Metagenomics Joseph A. Hakim 1,†, George B. H. Green 1, Stephen A. Watts 1, Michael R. Crowley 2, Casey D. Morrow 3,* and Asim K. Bej 1,* 1 Department of Biology, The University of Alabama at Birmingham, 1300 University Blvd., Birmingham, AL 35294, USA; [email protected] (J.A.H.); [email protected] (G.B.H.G.); [email protected] (S.A.W.) 2 Department of Genetics, Heflin Center Genomics Core, School of Medicine, The University of Alabama at Birmingham, 705 South 20th Street, Birmingham, AL 35294, USA; [email protected] 3 Department of Cell, Developmental and Integrative Biology, The University of Alabama at Birmingham, 1918 University Blvd., Birmingham, AL 35294, USA * Correspondence: [email protected] (C.D.M.); [email protected] (A.K.B.); Tel.: +1-205-934-5705 (C.D.M.); +1-205-934-9857 (A.K.B.) † Current Address: School of Medicine (M.D.), The University of Alabama at Birmingham, 1670 University Blvd, Birmingham, AL 35233, USA. Abstract: This paper describes the microbial community composition and genes for key metabolic genes, particularly the nitrogen fixation of the mucous-enveloped gut digesta of green (Lytechinus variegatus) and purple (Strongylocentrotus purpuratus) sea urchins by using the shotgun metagenomics Citation: Hakim, J.A.; Green, G.B.H.; approach. Both green and purple urchins showed high relative abundances of Gammaproteobacteria Watts, S.A.; Crowley, M.R.; Morrow, at 30% and 60%, respectively. However, Alphaproteobacteria in the green urchins had higher relative C.D.; Bej, A.K. -

Smithsonian at the Poles Contributions to International Polar Year Science

A Selection from Smithsonian at the Poles Contributions to International Polar Year Science Igor Krupnik, Michael A. Lang, and Scott E. Miller Editors A Smithsonian Contribution to Knowledge WASHINGTON, D.C. 2009 This proceedings volume of the Smithsonian at the Poles symposium, sponsored by and convened at the Smithsonian Institution on 3–4 May 2007, is published as part of the International Polar Year 2007–2008, which is sponsored by the International Council for Science (ICSU) and the World Meteorological Organization (WMO). Published by Smithsonian Institution Scholarly Press P.O. Box 37012 MRC 957 Washington, D.C. 20013-7012 www.scholarlypress.si.edu Text and images in this publication may be protected by copyright and other restrictions or owned by individuals and entities other than, and in addition to, the Smithsonian Institution. Fair use of copyrighted material includes the use of protected materials for personal, educational, or noncommercial purposes. Users must cite author and source of content, must not alter or modify content, and must comply with all other terms or restrictions that may be applicable. Cover design: Piper F. Wallis Cover images: (top left) Wave-sculpted iceberg in Svalbard, Norway (Photo by Laurie M. Penland); (top right) Smithsonian Scientifi c Diving Offi cer Michael A. Lang prepares to exit from ice dive (Photo by Adam G. Marsh); (main) Kongsfjorden, Svalbard, Norway (Photo by Laurie M. Penland). Library of Congress Cataloging-in-Publication Data Smithsonian at the poles : contributions to International Polar Year science / Igor Krupnik, Michael A. Lang, and Scott E. Miller, editors. p. cm. ISBN 978-0-9788460-1-5 (pbk. -

Echinodermata: Echinoidea) Alexander Ziegler*1, Cornelius Faber2 and Thomas Bartolomaeus3

Frontiers in Zoology BioMed Central Research Open Access Comparative morphology of the axial complex and interdependence of internal organ systems in sea urchins (Echinodermata: Echinoidea) Alexander Ziegler*1, Cornelius Faber2 and Thomas Bartolomaeus3 Address: 1Institut für Immungenetik, Charité-Universitätsmedizin Berlin, Freie Universität Berlin, Thielallee 73, 14195 Berlin, Germany, 2Institut für Klinische Radiologie, Universitätsklinikum Münster, Westfälische Wilhelms-Universität Münster, Waldeyerstraße 1, 48149 Münster, Germany and 3Institut für Evolutionsbiologie und Zooökologie, Rheinische Friedrich-Wilhelms-Universität Bonn, An der Immenburg 1, 53121 Bonn, Germany Email: Alexander Ziegler* - [email protected]; Cornelius Faber - [email protected]; Thomas Bartolomaeus - [email protected] * Corresponding author Published: 9 June 2009 Received: 4 December 2008 Accepted: 9 June 2009 Frontiers in Zoology 2009, 6:10 doi:10.1186/1742-9994-6-10 This article is available from: http://www.frontiersinzoology.com/content/6/1/10 © 2009 Ziegler et al; licensee BioMed Central Ltd. This is an Open Access article distributed under the terms of the Creative Commons Attribution License (http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/2.0), which permits unrestricted use, distribution, and reproduction in any medium, provided the original work is properly cited. Abstract Background: The axial complex of echinoderms (Echinodermata) is composed of various primary and secondary body cavities that interact with each other. In sea urchins (Echinoidea), structural differences of the axial complex in "regular" and irregular species have been observed, but the reasons underlying these differences are not fully understood. In addition, a better knowledge of axial complex diversity could not only be useful for phylogenetic inferences, but improve also an understanding of the function of this enigmatic structure. -

Redalyc.Echinoids of the Pacific Waters of Panama: Status Of

Revista de Biología Tropical ISSN: 0034-7744 [email protected] Universidad de Costa Rica Costa Rica Lessios, H.A. Echinoids of the Pacific Waters of Panama: Status of knowledge and new records Revista de Biología Tropical, vol. 53, núm. 3, -diciembre, 2005, pp. 147-170 Universidad de Costa Rica San Pedro de Montes de Oca, Costa Rica Available in: http://www.redalyc.org/articulo.oa?id=44919815009 How to cite Complete issue Scientific Information System More information about this article Network of Scientific Journals from Latin America, the Caribbean, Spain and Portugal Journal's homepage in redalyc.org Non-profit academic project, developed under the open access initiative Echinoids of the Pacific Waters of Panama: Status of knowledge and new records H.A. Lessios Smithsonian Tropical Research Institute, Apartado 0843-03092, Balboa, Panama; Fax: 507-212-8790; [email protected] Received 14-VI-2004. Corrected 09-XII-2004. Accepted 17-V-2005. Abstract: This paper is primarily intended as a guide to researchers who wish to know what echinoid species are available in the Bay of Panama and in the Gulf of Chiriqui, how to recognize them, and what has been published about them up to 2004. Fifty seven species of echinoids have been reported in the literature as occurring in the Pacific waters of Panama, of which I have collected and examined 31, including two species, Caenopedina diomediae and Meoma frangibilis, that have hitherto only been mentioned in the literature from single type specimens. For the 31 species I was able to examine, I list the localities in which they were found, my impression as to their relative abundance, the characters that distinguish them, and what is known about their biology and evolution. -

Taxonomy, Phylogeny and Paleobiogeography of the Cassiduloid Echinoids

Taxonomy, Phylogeny and Paleobiogeography of the Cassiduloid Echinoids By Camilla Alves Souto A dissertation submitted in partial satisfaction of the requirements for the degree of Doctor of Philosophy in Integrative Biology in the Graduate Division of the University of California, Berkeley Committee in charge: Professor Charles R. Marshall, Chair Professor Rauri Bowie Professor Kipling Will Professor Richard Mooi Fall 2018 Taxonomy, Phylogeny and Paleobiogeography of the Cassiduloid Echinoids Copyright 2018 by Camilla Alves Souto Abstract Taxonomy, Phylogeny and Paleobiogeography of the Cassiduloid Echinoids By Camilla Alves Souto Doctor of Philosophy in Integrative Biology University of California, Berkeley Professor Charles R. Marshall, Chair Cassiduloids are rare and poorly known irregular echinoids, which include the sand dollars and heart urchins, that typically live buried in the sediment, where they feed on small organic particles. Cassiduloids evolved during the Marine Mesozoic Revolution, but despite their rich fossil record, species richness (diversity) is very low. The goal of this thesis is to improve our taxonomic knowledge of the group, propose hypotheses of relationship among its representatives and analyze their patterns of geographic distribution through time, thereby contributing to our understanding of their evolutionary history. In the first chapter1, I used synchrotron radiation-based micro-computed tomography (SRµCT) images of type specimens to describe a new Cassidulus species and a new cassiduloid genus that could not have been discovered with traditional techniques. I also designate a neotype for the type species of the genus Cassidulus, Cassidulus caribaearum, provide remarks on the taxonomic history of each taxon, a diagnostic table of all living cassidulid species, and extend the known geographic and bathymetric range of two species.