Eleven Bullets: a Counter Assault on Subjectivity and the Creation of Meaning

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

The Metacomics of Alan Moore, Neil Gaiman, and Warren Ellis

University of Alberta Telling Stories About Storytelling: The Metacomics of Alan Moore, Neil Gaiman, and Warren Ellis by Orion Ussner Kidder A thesis submitted to the Faculty of Graduate Studies and Research in partial fulfilment of the requirements for the degree of Doctor of Philosophy in English Department of English and Film Studies ©Orion Ussner Kidder Spring 2010 Edmonton, Alberta Permission is hereby granted to the University of Alberta Libraries to reproduce single copies of this thesis and to lend or sell such copies for private, scholarly or scientific research purposes only. Where the thesis is converted to, or otherwise made available in digital form, the University of Alberta will advise potential users of the thesis of these terms. The author reserves all other publication and other rights in association with the copyright in the thesis and, except as herein before provided, neither the thesis nor any substantial portion thereof may be printed or otherwise reproduced in any material form whatsoever without the author's prior written permission. Library and Archives Bibliothèque et Canada Archives Canada Published Heritage Direction du Branch Patrimoine de l’édition 395 Wellington Street 395, rue Wellington Ottawa ON K1A 0N4 Ottawa ON K1A 0N4 Canada Canada Your file Votre référence ISBN: 978-0-494-60022-1 Our file Notre référence ISBN: 978-0-494-60022-1 NOTICE: AVIS: The author has granted a non- L’auteur a accordé une licence non exclusive exclusive license allowing Library and permettant à la Bibliothèque et Archives Archives Canada to reproduce, Canada de reproduire, publier, archiver, publish, archive, preserve, conserve, sauvegarder, conserver, transmettre au public communicate to the public by par télécommunication ou par l’Internet, prêter, telecommunication or on the Internet, distribuer et vendre des thèses partout dans le loan, distribute and sell theses monde, à des fins commerciales ou autres, sur worldwide, for commercial or non- support microforme, papier, électronique et/ou commercial purposes, in microform, autres formats. -

Mcwilliams Ku 0099D 16650

‘Yes, But What Have You Done for Me Lately?’: Intersections of Intellectual Property, Work-for-Hire, and The Struggle of the Creative Precariat in the American Comic Book Industry © 2019 By Ora Charles McWilliams Submitted to the graduate degree program in American Studies and the Graduate Faculty of the University of Kansas in partial fulfillment of the requirements for the degree of Doctor of Philosophy. Co-Chair: Ben Chappell Co-Chair: Elizabeth Esch Henry Bial Germaine Halegoua Joo Ok Kim Date Defended: 10 May, 2019 ii The dissertation committee for Ora Charles McWilliams certifies that this is the approved version of the following dissertation: ‘Yes, But What Have You Done for Me Lately?’: Intersections of Intellectual Property, Work-for-Hire, and The Struggle of the Creative Precariat in the American Comic Book Industry Co-Chair: Ben Chappell Co-Chair: Elizabeth Esch Date Approved: 24 May 2019 iii Abstract The comic book industry has significant challenges with intellectual property rights. Comic books have rarely been treated as a serious art form or cultural phenomenon. It used to be that creating a comic book would be considered shameful or something done only as side work. Beginning in the 1990s, some comic creators were able to leverage enough cultural capital to influence more media. In the post-9/11 world, generic elements of superheroes began to resonate with audiences; superheroes fight against injustices and are able to confront the evils in today’s America. This has created a billion dollar, Oscar-award-winning industry of superhero movies, as well as allowed created comic book careers for artists and writers. -

Quick Guide Is Online

SAN DIEGO SAN DIEGO MARRIOTT CONVENTION MARQUIS & MARINA CENTER JULY 18–21 • PREVIEW NIGHT JULY 17 QUICKQUICK GUIDEGUIDE SCHEDULE GRIDS • EXHIBIT HALL MAP • CONVENTION CENTER & HOTEL MAPS HILTON SAN DIEGO BAYFRONT MANCHESTER GRAND HYATT ONLINE EDITION INFORMATION IS SUBJECT TO CHANGE MAPu HOTELS AND SHUTTLE STOPS MAP 1 28 10 24 47 48 33 2 4 42 34 16 20 21 9 59 3 50 56 31 14 38 58 52 6 54 53 11 LYCEUM 57 THEATER 1 19 40 41 THANK YOU TO OUR GENEROUS SHUTTLE 36 30 SPONSOR FOR COMIC-CON 2013: 32 38 43 44 45 THANK YOU TO OUR GENEROUS SHUTTLE SPONSOR OF COMIC‐CON 2013 26 23 60 37 51 61 25 46 18 49 55 27 35 8 13 22 5 17 15 7 12 Shuttle Information ©2013 S�E�A�T Planners Incorporated® Subject to change ℡619‐921‐0173 www.seatplanners.com and traffic conditions MAP KEY • MAP #, LOCATION, ROUTE COLOR 1. Andaz San Diego GREEN 18. DoubleTree San Diego Mission Valley PURPLE 35. La Quinta Inn Mission Valley PURPLE 50. Sheraton Suites San Diego Symphony Hall GREEN 2. Bay Club Hotel and Marina TEALl 19. Embassy Suites San Diego Bay PINK 36. Manchester Grand Hyatt PINK 51. uTailgate–MTS Parking Lot ORANGE 3. Best Western Bayside Inn GREEN 20. Four Points by Sheraton SD Downtown GREEN 37. uOmni San Diego Hotel ORANGE 52. The Sofia Hotel BLUE 4. Best Western Island Palms Hotel and Marina TEAL 21. Hampton Inn San Diego Downtown PINK 38. One America Plaza | Amtrak BLUE 53. The US Grant San Diego BLUE 5. -

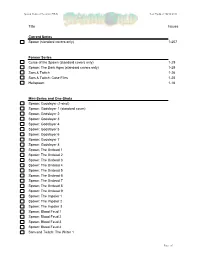

Spawn Comics Checklist (USA)

Spawn Comics Checklist (USA) Last Updated: 06/18/2011 Title Issues Current Series Spawn (standard covers only) 1-207 Former Series Curse of the Spawn (standard covers only) 1-29 Spawn: The Dark Ages (standard covers only) 1-28 Sam & Twitch 1-26 Sam & Twitch: Case Files 1-25 Hellspawn 1-16 Mini-Series and One-Shots Spawn: Godslayer (1-shot) Spawn: Godslayer 1 (standard cover) Spawn: Godslayer 2 Spawn: Godslayer 3 Spawn: Godslayer 4 Spawn: Godslayer 5 Spawn: Godslayer 6 Spawn: Godslayer 7 Spawn: Godslayer 8 Spawn: The Undead 1 Spawn: The Undead 2 Spawn: The Undead 3 Spawn: The Undead 4 Spawn: The Undead 5 Spawn: The Undead 6 Spawn: The Undead 7 Spawn: The Undead 8 Spawn: The Undead 9 Spawn: The Impaler 1 Spawn: The Impaler 2 Spawn: The Impaler 3 Spawn: Blood Feud 1 Spawn: Blood Feud 2 Spawn: Blood Feud 3 Spawn: Blood Feud 4 Sam and Twitch: The Writer 1 Page of Spawn Comics Checklist (USA) Last Updated: 06/18/2011 Sam and Twitch: The Writer 2 Sam and Twitch: The Writer 3 Sam and Twitch: The Writer 4 Angela 1 Angela 2 Angela 3 Cy-Gor 1 Cy-Gor 2 Cy-Gor 3 Cy-Gor 4 Cy-Gor 5 Cy-Gor 6 Violator 1 Violator 2 Violator 3 Spawn: Blood & Shadows (Annual 1) Spawn Bible (1st Print) Spawn Bible (2nd Print) Spawn Bible (3rd Print) Spawn: Book of Souls Spawn: Blood & Salvation Spawn: Simony Spawn: Architects of Fear The Adventures of Spawn Director’s Cut The Adventures of Spawn 2 Celestine 1 (green) Celestine 1 (purple) Celestine 2 Spawn Manga (Shadows of Spawn) vol1 (1st Print) Spawn Manga (Shadows of Spawn) vol1 (2nd Print) Spawn Manga (Shadows of Spawn) -

Friday at Comic Con Files/SDCC Fridays Newsletter.Pdf

FRIDAY ANIME • FILM FESTIVAL • FILMS ANIME SCREENINGS • MARRIOTT MARQUIS & MARINA COMIC-CON T O D AY MARRIOTT HALL 4 MARRIOTT HALL 5 MARRIOTT HALL 6 INTERNATIONAL INDEPENDENT 10:00 Someday’s Dreamers 10:00 Clamp School Detectives 10:00 Gad Guard FILM FESTIVAL Daily Newsletter of Comic-Con International 10:25 True Tears 10:25 And Yet the Town Moves 10:25 Gao-Gai-Gar MARRIOTT HALL 2 10:50 Kobato 10:50 Squid Girl 10:50 Mobile Suit Gundam 0079 Friday, July 13, 2012 11:15 AnoHana: The Flower We Saw 11:15 Lucky Star 11:15 Tiger & Bunny 10:00 Comic-Con Film School 102 That Day 11:40 Kimi Ni Todoke-From Me to You 11:40 Escaflowne 11:40 Super Gals 2 12:05 Ramen Fighter Miki 12:05 Gasaraki COMICS-ORIENTED 12:05 Kekkaishi 12:30 Aria the Natural 12:30 Mobile Suit Zeta Gundam 11:05 Paula Peril: Midnight Whistle 12:30 You’re Under Arrest 3 12:55 A-Channel 12:55 Gun X Sword 11:50 Super to the Heroes 12:55 Zakuro 1:20 Bakuman 1:20 Psychic Squad 12:00 Lost Rites 1:20 Fairy Tail 1:45 K-ON! 1:45 Dirty Pair 12:25 Prelude to Bedlam 1:45 Fushigi Yugi 2:10 Oreimo 2:10 Broken Blade Featuring: 2:10 Nura: Rise of the Yokai Clan 2:35 Kanon 3:00 Sound of the Sky PANEL 2:35 The Melancholy of Haruhi- 3:00 The Melancholy of Haruhi-Chan 3:25 Gin Tama 1:15 From Fanboy to Filmmaker: Chan Suzumiya Suzumiya * Highlights 3:50 Dirty Pair Flash A Case Study on How to 2:40 Rental Magica 3:05 Toradora! 4:20 Full Metal Alchemist: Make a Successful Animated 3:05 Puella Magi Madoka Magica 3:30 Hayate the Combat Butler Brotherhood Film 3:30 Legend of the Legendary Heroes 3:55 Nyan -

Crisis of Infinite Intertexts! Continuity As Adaptation in the Superman Multimedia Franchise

Crisis of Infinite Intertexts! Continuity as Adaptation in the Superman Multimedia Franchise Jack Peterson Teiwes ORCID identifier 0000-0001-8956-1602 Doctor of Philosophy November 2015 School of Culture and Communication The University of Melbourne Submitted in total fulfillment of the requirements of the PhD degree Produced on archival quality paper Abstract Since first appearing as a comic book character over three quarters of a century ago, Superman was not only the first superhero, spawning an entire genre of imitators, but also quickly became one of the most widely disseminated multi-media entertainment franchises. This achieved a degree of intergenerational cultural dissemination that far surpasses his comic book fandom. Yet despite an unprecedented degree of adaptation into other media from radio, newspaper strips, film serials, animation, feature films, video games and television, Superman’s ongoing comic books have remained in unbroken publication, developing a long and complex history of narrative renewal and reinvention. This thesis investigates the multifaceted intertextuality between the comic book portrayals of Superman and its many adaptations over the years, including how such retellings in other media have a generally stronger cultural impact, which exerts in turn an adaptive influence upon these continuing comics’ internalised narrative continuity. I shall argue that Superman comics, as a case study for the wider phenomenon in the superhero genre, demonstrate via their frequent revisions and relaunches of continuity, a process of deeply palimpsestuous self-adaptation. The Introduction positions my research methodology in relation to intertextual theory, with an emphasis on providing terminological clarity, while Chapter 1 expands into a literature review on pertinent key scholarship on adaptation studies and the comics studies field specifically. -

The Biological Basis of Marvel Comics Mutants

Journal of Geek Studies jgeekstudies.org The biological basis of Marvel Comics mutants Damián E. Pérez Instituto Patagónico de Geología y Paleontología (IPGP CCT CONICET- CENPAT), Puerto Madryn, Chubut, Argentina. E-mail: [email protected] “Feared and hated by a world they have changes in human offspring, and mutants sworn to protect” is the catchphrase always were the consequence (Accorsi & Accorsi, present in nearly all comics of Marvel’s mu- 1994; Clemente, 2000; Kakalios, 2005). tants, the X-Men. This phrase was coined by Stan Lee, the co-creator of the X-Men to- Beyond Stan Lee and Jack Kirby, this is gether with Jack Kirby. A popular proverb the same concept used in the Japanese God states that “we fear what we do not under- zilla films of previous years. Thus, the word stand” and this is probably the case with ‘mutant’ was often used in sci-fi literature the mutants within Marvel’s comic book of the 1950s to designate human varia- universe. Therefore, the question is: can we tions with strange superpowers. The term understand Marvel’s mutants? That is the was used a few times during those years in main aim of this essay. some Atlas (previous name of Marvel Com- ics editorial during the 1950s) comic books The word ‘mutant’ is often found in sci- from 1952 to 1963 (for example, in Tales of ence fiction literature, television and mov- Suspense #6, from 1959). Officially, accord- ies. The mutant condition is not an inven- ing to the established cannon, the first time tion of these arts and media. -

A Pictorial History of Comic-Con

A PICTORIAL HISTORY OF COMIC-CON The 2010s THE NOW AGE OF COMIC-CON Comic-Con exploded around the world in the “now” age of social media. It became the show everyone wanted to go to as it expanded into other sites, including hotels and the new San Diego Central Library, creating a downtown campus. COMIC-CON 50 www.comic-con.org 1 OPPOSITE PAGE, TOP ROW LEFT: Jill Thompson sure was pleased to get an Eisner Award. 2010 RIGHT: Manga great 2010 COMIC-CON 41 Moto Hagio had one COMIC-CON 41 request of Comic- Con: Could she please meet Ray Bradbury? NOTABLE JULY 22–25 SECOND ROW, LEFT TO RIGHT: Former GUESTS DC Comics publisher San Diego Jenette Kahn was an Inkpot Award Convention recipient; artist Jillian Center Tamaki; Darkseid schemed. BERKELEY BREATHED THIRD ROW, LEFT: Syndicated cartoonist, Attendance: J. J. Abrams and Joss 126,000 Whedon had a meet- Bloom County, Opus ing of the minds in Hall H. MATT FRACTION Comic-Con entered the second de- RIGHT: Comic book cade of the new millennium with writer Brian Michael Comic book writer, still more expansion to the nearby Bendis with his Inkpot Award. Iron Man, Iron Fist hotels. It added a second day of pro- gramming to the Indigo Ballroom in BOTTOM: The cast of the Hilton San Diego Bayfront, which The Big Bang Theory MOTO HAGIO hosted the Eisner Awards for the very backstage in Hall H. first time. Events such as the CCI-IFF, Manga writer-artist, the fan groups meeting room, and THIS PAGE, TOP A Drunken Dream the anime rooms moved offsite to the AND RIGHT: DC Comics celebrated and Other Stories Marriott Marquis Hotel and Marina their 75th anniver- next door. -

RAynor's ARtfully PRofiled HIs IDeal COmics, Or

Gosh! Raynor's Artfully Profiled His Ideal Comics, or GRAPHIC Edited by Raynor Kuang Questions by Raynor Kuang, Jarret Greene, Aaron Kashtan, Erik Owen And with thanks to Peter Parker, Bruce Wayne, and L. Kuang, the heroes of my childhood Round 6 Tossups 1. In Neil Gaiman’s story “Hold Me,” this character hugs the ghost of a homelass man. Jamie Delano’s run with this character ended with his confrontation of the serial killer the Family Man. This character tried to combat a demon summoned by the child Astra while on tour with his band (*) Mucous Membrane in Newgate. This character’s exes include Nick Necro and Zatanna. Garth Ennis’s run with this character included the story “Dangerous Habits,” which showed him contracting lung cancer. This character was the protagonist of Vertigo’s Hellblazer series, in which he was depicted as a trenchcoatwearing Brit modeled after Sting. For 10 points, name this chain smoking occult detective and sorceror. ANSWER: John Constantine (accept either or both names; accept Hellblazer before mention) 2. This character killed Prince Gavyn’s sister and took over Throneworld. After taking over a planet whose inhabitants all died of a virus, this character discovered two immune infants he raised as his own. This character was eventually killed by the demon Neron, and he was defeated and replaced in his initial position by (*) Draaga. After being recruited by the Cyborg Superman, this villain destroyed Coastal City. In “For the Man Who Has Everything,” this villain causes Superman to see a reality of himself living on Krypton after infecting Superman with the plant Black Mercy, and he’d earlier fought Superman as a gladiator on a massive planetsize spaceship. -

No.102$8.95 Deadpool and Cable TM & © Marvel Characters, Inc

Deadpool and Cable TM & © Marvel Characters, Inc. All Rights Reserved. No.102 February 2018 $8.95 1 82658 00116 2 INTERVIEW WITH DEADPOOL’S FIRST WRITER,FABIANNICIEZA FIRST INTERVIEW WITHDEADPOOL’S Punisher! Featuring Beatty, Claremont, Collins,Lash, Michelinie, anda Liefeldcover! Deathstroke •VigilanteTaskmaster •WildDogCable •andArchieMeets the ISSUE!MERCS &ANTI-HEROES ™ Volume 1, Number 102 February 2018 EDITOR-IN-CHIEF Michael Eury PUBLISHER Comics’ Bronze Age and Beyond! John Morrow DESIGNER Rich Fowlks COVER ARTIST Rob Liefeld COVER COLORIST Glenn Whitmore COVER DESIGNER Michael Kronenberg PROOFREADER Rob Smentek SPECIAL THANKS Terry Beatty Bob McLeod Jarrod Buttery David Michelinie Marc Buxton Fabian Nicieza Joe Casey Luigi Novi Ian Churchill Scott Nybakken Shaun Clancy Chuck Patton Max Allan Collins Philip Schweier FLASHBACK: Deathstroke the Terminator 2 Brian Cronin David Scroggy A bullet-riddled bio of the New Teen Titans breakout star Grand Comics Ken Siu-Chong Database Tod Smith BRING ON THE BAD GUYS: Taskmaster 17 Tom DeFalco Anthony Snyder Is he really the best at everything he does? Christos Gage Allen Stewart Mike Grell Steven Thompson FLASHBACK: The Vigilante 23 Gene Ha Fred Van Lente Who were those masked men in this New Teen Titans spinoff? Heritage Comics Marv Wolfman Auctions Doug Zawisza FLASHBACK: Wild Dog 36 Sean Howe Mike Zeck Max Allan Collins and Terry Beatty unmask DC’s ’80s vigilante Brian Ko Paul Kupperberg ROUGH STUFF 42 James Heath Lantz Grim-and-gritty graphite from Grell, Wrightson, Zeck, and Liefeld -

What the NFT World Can Learn from the Great '90S Comic Book Bubble

What the NFT World Can Learn From the Great ’90s Comic Book Bubble. (It’s a Cautionary Tale) Lessons for Beeple and Grimes from the days of Deadpool and Spawn. Ben Davis, March 30, 2021 Cosplay enthusiasts dressed up as Harley Quinn and Deadpool at the Romics event, on April 8, 2017. Photo by Alberto Pizzoli/AFP via Getty ImaGes. I was giving a lecture to an undergraduate class at NYU a few weeks ago. NFTs were not the subject, but in the Q&A period one student asked me what I thought about NFTs. I told him I was watching the space, but hadn’t much to say yet, and asked what he thought. He said NFTs were the future, that in a generation they would be the only art that matters, and he kept reeling off prices: this CryptoPunk went for this amount, such and such sold for so much on Nifty Gateway, etc. I kept trying to bring the conversation back around: “Yes, but what do you like about these images as art?” He kept coming back at me with the prices. Finally, after I raised the art question one last time, he said in exasperation: “Ben, when the Maurizio Cattelan banana sold at Art Basel—what was the headline? The money! The money is the art.” (I’m paraphrasing, of course, but it’s close.) Fairgoers take pictures of Maurizio Cattelan’s Comedian, for sale from Perrotin at Art Basel Miami Beach. Photo by Sarah Cascone. “People are paying [insert outrageous price] for [insert unbelievable thing]?!?” is one of two or three archetypal art stories, as far as the popular interest is concerned. -

ARCHIE COMICS Random House Adult Blue Omni, Fall 2013 Archie

ARCHIE COMICS Random House Adult Blue Omni, Fall 2013 Archie Comics The Best of Archie Comics 3 Summary: It's Archie's third volume in our all-time Archie Superstars bestselling The Best of Archie Comics graphic novel series, 9781936975617 featuring even more great stories from Archie's eight decades Pub Date: 9/3/13, On Sale Date: 9/3 of excellence! This fun full-color collection of more of Archie's Ages 10 And Up, Grades 5 And Up all-time favorite stories, lovingly hand-selected and $9.99/$10.99 Can. introduced by Archie creators, editors, and historians from 416 pages / FULL-COLOR ILLUSTRATIONS 200,000 pages of material, is a must-have for any Archie fan THROUGHOUT and fans of comics in general, as well as a great introduction Paperback / softback / Digest format paperback to the comics medium! Juvenile Fiction / Comics & Graphic Novels ... Series: The Best Of Archie ComicsTerritory: World Ctn Qty: 1 Author Bio: THE ARCHIE SUPERSTARS are the impressive 5.250 in W | 7.500 in H line-up of talented writers and artists who have brought 133mm W | 191mm H Archie, his friends and his world to life for more than 70 years, from legends such as Dan DeCarlo, Frank Doyle, Harry Lucey, and Bob Montana to recent greats like Dan Parent and Fernando Ruiz, and many more! Random House Adult Blue Omni, Fall 2013 Archie Comics Sabrina the Teenage Witch: The Magic Within 3 Summary: Return to the magic with Sabrina the Teenage Tania del Rio Witch: The Magic Within 3! 9781936975600 Pub Date: 9/10/13, On Sale Date: 9/10 Sabrina and friends become caught up in the secrets of the Ages 10 And Up, Grades 5 And Up Magic Realm, while friendships and relationships are put to the $10.99/$11.99 Can.