Deltoid* the Deltoid Curve Was Conceived by Euler in 1745 in Con

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

On Ramified Covers of the Projective Plane I: Segre's Theory And

ON RAMIFIED COVERS OF THE PROJECTIVE PLANE I: SEGRE’S THEORY AND CLASSIFICATION IN SMALL DEGREES (WITH AN APPENDIX BY EUGENII SHUSTIN) MICHAEL FRIEDMAN AND MAXIM LEYENSON1 Abstract. We study ramified covers of the projective plane P2. Given a smooth surface S in Pn and a generic enough projection Pn → P2, we get a cover π : S → P2, which is ramified over a plane curve B. The curve B is usually singular, but is classically known to have only cusps and nodes as singularities for a generic projection. Several questions arise: First, What is the geography of branch curves among all cuspidal-nodal curves? And second, what is the geometry of branch curves; i.e., how can one distinguish a branch curve from a non-branch curve with the same numerical invariants? For example, a plane sextic with six cusps is known to be a branch curve of a generic projection iff its six cusps lie on a conic curve, i.e., form a special 0-cycle on the plane. We start with reviewing what is known about the answers to these questions, both simple and some non-trivial results. Secondly, the classical work of Beniamino Segre gives a complete answer to the second question in the case when S is a smooth surface in P3. We give an interpretation of the work of Segre in terms of relation between Picard and Chow groups of 0-cycles on a singular plane curve B. We also review examples of small degree. In addition, the Appendix written by E. Shustin shows the existence of new Zariski pairs. -

Plotting Graphs of Parametric Equations

Parametric Curve Plotter This Java Applet plots the graph of various primary curves described by parametric equations, and the graphs of some of the auxiliary curves associ- ated with the primary curves, such as the evolute, involute, parallel, pedal, and reciprocal curves. It has been tested on Netscape 3.0, 4.04, and 4.05, Internet Explorer 4.04, and on the Hot Java browser. It has not yet been run through the official Java compilers from Sun, but this is imminent. It seems to work best on Netscape 4.04. There are problems with Netscape 4.05 and it should be avoided until fixed. The applet was developed on a 200 MHz Pentium MMX system at 1024×768 resolution. (Cost: $4000 in March, 1997. Replacement cost: $695 in June, 1998, if you can find one this slow on sale!) For various reasons, it runs extremely slowly on Macintoshes, and slowly on Sun Sparc stations. The curves should move as quickly as Roadrunner cartoons: for a benchmark, check out the circular trigonometric diagrams on my Java page. This applet was mainly done as an exercise in Java programming leading up to more serious interactive animations in three-dimensional graphics, so no attempt was made to be comprehensive. Those who wish to see much more comprehensive sets of curves should look at: http : ==www − groups:dcs:st − and:ac:uk= ∼ history=Java= http : ==www:best:com= ∼ xah=SpecialP laneCurve dir=specialP laneCurves:html http : ==www:astro:virginia:edu= ∼ eww6n=math=math0:html Disclaimer: Like all computer graphics systems used to illustrate mathematical con- cepts, it cannot be error-free. -

Combination of Cubic and Quartic Plane Curve

IOSR Journal of Mathematics (IOSR-JM) e-ISSN: 2278-5728,p-ISSN: 2319-765X, Volume 6, Issue 2 (Mar. - Apr. 2013), PP 43-53 www.iosrjournals.org Combination of Cubic and Quartic Plane Curve C.Dayanithi Research Scholar, Cmj University, Megalaya Abstract The set of complex eigenvalues of unistochastic matrices of order three forms a deltoid. A cross-section of the set of unistochastic matrices of order three forms a deltoid. The set of possible traces of unitary matrices belonging to the group SU(3) forms a deltoid. The intersection of two deltoids parametrizes a family of Complex Hadamard matrices of order six. The set of all Simson lines of given triangle, form an envelope in the shape of a deltoid. This is known as the Steiner deltoid or Steiner's hypocycloid after Jakob Steiner who described the shape and symmetry of the curve in 1856. The envelope of the area bisectors of a triangle is a deltoid (in the broader sense defined above) with vertices at the midpoints of the medians. The sides of the deltoid are arcs of hyperbolas that are asymptotic to the triangle's sides. I. Introduction Various combinations of coefficients in the above equation give rise to various important families of curves as listed below. 1. Bicorn curve 2. Klein quartic 3. Bullet-nose curve 4. Lemniscate of Bernoulli 5. Cartesian oval 6. Lemniscate of Gerono 7. Cassini oval 8. Lüroth quartic 9. Deltoid curve 10. Spiric section 11. Hippopede 12. Toric section 13. Kampyle of Eudoxus 14. Trott curve II. Bicorn curve In geometry, the bicorn, also known as a cocked hat curve due to its resemblance to a bicorne, is a rational quartic curve defined by the equation It has two cusps and is symmetric about the y-axis. -

On the Topology of Hypocycloid Curves

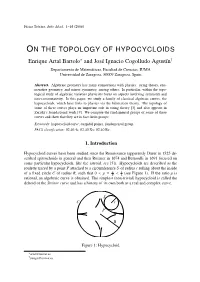

Física Teórica, Julio Abad, 1–16 (2008) ON THE TOPOLOGY OF HYPOCYCLOIDS Enrique Artal Bartolo∗ and José Ignacio Cogolludo Agustíny Departamento de Matemáticas, Facultad de Ciencias, IUMA Universidad de Zaragoza, 50009 Zaragoza, Spain Abstract. Algebraic geometry has many connections with physics: string theory, enu- merative geometry, and mirror symmetry, among others. In particular, within the topo- logical study of algebraic varieties physicists focus on aspects involving symmetry and non-commutativity. In this paper, we study a family of classical algebraic curves, the hypocycloids, which have links to physics via the bifurcation theory. The topology of some of these curves plays an important role in string theory [3] and also appears in Zariski’s foundational work [9]. We compute the fundamental groups of some of these curves and show that they are in fact Artin groups. Keywords: hypocycloid curve, cuspidal points, fundamental group. PACS classification: 02.40.-k; 02.40.Xx; 02.40.Re . 1. Introduction Hypocycloid curves have been studied since the Renaissance (apparently Dürer in 1525 de- scribed epitrochoids in general and then Roemer in 1674 and Bernoulli in 1691 focused on some particular hypocycloids, like the astroid, see [5]). Hypocycloids are described as the roulette traced by a point P attached to a circumference S of radius r rolling about the inside r 1 of a fixed circle C of radius R, such that 0 < ρ = R < 2 (see Figure 1). If the ratio ρ is rational, an algebraic curve is obtained. The simplest (non-trivial) hypocycloid is called the deltoid or the Steiner curve and has a history of its own both as a real and complex curve. -

Around and Around ______

Andrew Glassner’s Notebook http://www.glassner.com Around and around ________________________________ Andrew verybody loves making pictures with a Spirograph. The result is a pretty, swirly design, like the pictures Glassner EThis wonderful toy was introduced in 1966 by Kenner in Figure 1. Products and is now manufactured and sold by Hasbro. I got to thinking about this toy recently, and wondered The basic idea is simplicity itself. The box contains what might happen if we used other shapes for the a collection of plastic gears of different sizes. Every pieces, rather than circles. I wrote a program that pro- gear has several holes drilled into it, each big enough duces Spirograph-like patterns using shapes built out of to accommodate a pen tip. The box also contains some Bezier curves. I’ll describe that later on, but let’s start by rings that have gear teeth on both their inner and looking at traditional Spirograph patterns. outer edges. To make a picture, you select a gear and set it snugly against one of the rings (either inside or Roulettes outside) so that the teeth are engaged. Put a pen into Spirograph produces planar curves that are known as one of the holes, and start going around and around. roulettes. A roulette is defined by Lawrence this way: “If a curve C1 rolls, without slipping, along another fixed curve C2, any fixed point P attached to C1 describes a roulette” (see the “Further Reading” sidebar for this and other references). The word trochoid is a synonym for roulette. From here on, I’ll refer to C1 as the wheel and C2 as 1 Several the frame, even when the shapes Spirograph- aren’t circular. -

Generalization of the Pedal Concept in Bidimensional Spaces. Application to the Limaçon of Pascal• Generalización Del Concep

Generalization of the pedal concept in bidimensional spaces. Application to the limaçon of Pascal• Irene Sánchez-Ramos a, Fernando Meseguer-Garrido a, José Juan Aliaga-Maraver a & Javier Francisco Raposo-Grau b a Escuela Técnica Superior de Ingeniería Aeronáutica y del Espacio, Universidad Politécnica de Madrid, Madrid, España. [email protected], [email protected], [email protected] b Escuela Técnica Superior de Arquitectura, Universidad Politécnica de Madrid, Madrid, España. [email protected] Received: June 22nd, 2020. Received in revised form: February 4th, 2021. Accepted: February 19th, 2021. Abstract The concept of a pedal curve is used in geometry as a generation method for a multitude of curves. The definition of a pedal curve is linked to the concept of minimal distance. However, an interesting distinction can be made for . In this space, the pedal curve of another curve C is defined as the locus of the foot of the perpendicular from the pedal point P to the tangent2 to the curve. This allows the generalization of the definition of the pedal curve for any given angle that is not 90º. ℝ In this paper, we use the generalization of the pedal curve to describe a different method to generate a limaçon of Pascal, which can be seen as a singular case of the locus generation method and is not well described in the literature. Some additional properties that can be deduced from these definitions are also described. Keywords: geometry; pedal curve; distance; angularity; limaçon of Pascal. Generalización del concepto de curva podal en espacios bidimensionales. Aplicación a la Limaçon de Pascal Resumen El concepto de curva podal está extendido en la geometría como un método generativo para multitud de curvas. -

On the Topology of Hypocycloids

ON THE TOPOLOGY OF HYPOCYCLOIDS ENRIQUE ARTAL BARTOLO AND JOSE´ IGNACIO COGOLLUDO-AGUST´IN Abstract. Algebraic geometry has many connections with physics: string theory, enumerative geometry, and mirror symmetry, among others. In par- ticular, within the topological study of algebraic varieties physicists focus on aspects involving symmetry and non-commutativity. In this paper, we study a family of classical algebraic curves, the hypocycloids, which have links to physics via the bifurcation theory. The topology of some of these curves plays an important role in string theory [3] and also appears in Zariski’s foundational work [9]. We compute the fundamental groups of some of these curves and show that they are in fact Artin groups. 1. Introduction Hypocycloid curves have been studied since the Renaissance (apparently D¨urer in 1525 described epitrochoids in general and then Roemer in 1674 and Bernoulli in 1691 focused on some particular hypocycloids, like the astroid, see [5]). Hypocy- cloids are described as the roulette traced by a point P attached to a circumference S of radius r rolling about the inside of a fixed circle C of radius R, such that r 1 0 < ρ = R < 2 (see Figure 1). If the ratio ρ is rational, an algebraic curve is ob- tained. The simplest (non-trivial) hypocycloid is called the deltoid or the Steiner curve and has a history of its own both as a real and complex curve. S r C P arXiv:1703.08308v1 [math.AG] 24 Mar 2017 R Figure 1. Hypocycloid Key words and phrases. hypocycloid curve, cuspidal points, fundamental group. -

Strophoids, a Family of Cubic Curves with Remarkable Properties

Hellmuth STACHEL STROPHOIDS, A FAMILY OF CUBIC CURVES WITH REMARKABLE PROPERTIES Abstract: Strophoids are circular cubic curves which have a node with orthogonal tangents. These rational curves are characterized by a series or properties, and they show up as locus of points at various geometric problems in the Euclidean plane: Strophoids are pedal curves of parabolas if the corresponding pole lies on the parabola’s directrix, and they are inverse to equilateral hyperbolas. Strophoids are focal curves of particular pencils of conics. Moreover, the locus of points where tangents through a given point contact the conics of a confocal family is a strophoid. In descriptive geometry, strophoids appear as perspective views of particular curves of intersection, e.g., of Viviani’s curve. Bricard’s flexible octahedra of type 3 admit two flat poses; and here, after fixing two opposite vertices, strophoids are the locus for the four remaining vertices. In plane kinematics they are the circle-point curves, i.e., the locus of points whose trajectories have instantaneously a stationary curvature. Moreover, they are projections of the spherical and hyperbolic analogues. For any given triangle ABC, the equicevian cubics are strophoids, i.e., the locus of points for which two of the three cevians have the same lengths. On each strophoid there is a symmetric relation of points, so-called ‘associated’ points, with a series of properties: The lines connecting associated points P and P’ are tangent of the negative pedal curve. Tangents at associated points intersect at a point which again lies on the cubic. For all pairs (P, P’) of associated points, the midpoints lie on a line through the node N. -

A Special Conic Associated with the Reuleaux Negative Pedal Curve

INTERNATIONAL JOURNAL OF GEOMETRY Vol. 10 (2021), No. 2, 33–49 A SPECIAL CONIC ASSOCIATED WITH THE REULEAUX NEGATIVE PEDAL CURVE LILIANA GABRIELA GHEORGHE and DAN REZNIK Abstract. The Negative Pedal Curve of the Reuleaux Triangle w.r. to a pedal point M located on its boundary consists of two elliptic arcs and a point P0. Intriguingly, the conic passing through the four arc endpoints and by P0 has one focus at M. We provide a synthetic proof for this fact using Poncelet’s porism, polar duality and inversive techniques. Additional interesting properties of the Reuleaux negative pedal w.r. to pedal point M are also included. 1. Introduction Figure 1. The sides of the Reuleaux Triangle R are three circular arcs of circles centered at each Reuleaux vertex Vi; i = 1; 2; 3. of an equilateral triangle. The Reuleaux triangle R is the convex curve formed by the arcs of three circles of equal radii r centered on the vertices V1;V2;V3 of an equilateral triangle and that mutually intercepts in these vertices; see Figure1. This triangle is mostly known due to its constant width property [4]. Keywords and phrases: conic, inversion, pole, polar, dual curve, negative pedal curve. (2020)Mathematics Subject Classification: 51M04,51M15, 51A05. Received: 19.08.2020. In revised form: 26.01.2021. Accepted: 08.10.2020 34 Liliana Gabriela Gheorghe and Dan Reznik Figure 2. The negative pedal curve N of the Reuleaux Triangle R w.r. to a point M on its boundary consist on an point P0 (the antipedal of M through V3) and two elliptic arcs A1A2 and B1B2 (green and blue). -

Generating Negative Pedal Curve Through Inverse Function – an Overview *Ramesha

© 2017 JETIR March 2017, Volume 4, Issue 3 www.jetir.org (ISSN-2349-5162) Generating Negative pedal curve through Inverse function – An Overview *Ramesha. H.G. Asst Professor of Mathematics. Govt First Grade College, Tiptur. Abstract This paper attempts to study the negative pedal of a curve with fixed point O is therefore the envelope of the lines perpendicular at the point M to the lines. In inversive geometry, an inverse curve of a given curve C is the result of applying an inverse operation to C. Specifically, with respect to a fixed circle with center O and radius k the inverse of a point Q is the point P for which P lies on the ray OQ and OP·OQ = k2. The inverse of the curve C is then the locus of P as Q runs over C. The point O in this construction is called the center of inversion, the circle the circle of inversion, and k the radius of inversion. An inversion applied twice is the identity transformation, so the inverse of an inverse curve with respect to the same circle is the original curve. Points on the circle of inversion are fixed by the inversion, so its inverse is itself. is a function that "reverses" another function: if the function f applied to an input x gives a result of y, then applying its inverse function g to y gives the result x, and vice versa, i.e., f(x) = y if and only if g(y) = x. The inverse function of f is also denoted. -

The Cycloid Scott Morrison

The cycloid Scott Morrison “The time has come”, the old man said, “to talk of many things: Of tangents, cusps and evolutes, of curves and rolling rings, and why the cycloid’s tautochrone, and pendulums on strings.” October 1997 1 Everyone is well aware of the fact that pendulums are used to keep time in old clocks, and most would be aware that this is because even as the pendu- lum loses energy, and winds down, it still keeps time fairly well. It should be clear from the outset that a pendulum is basically an object moving back and forth tracing out a circle; hence, we can ignore the string or shaft, or whatever, that supports the bob, and only consider the circular motion of the bob, driven by gravity. It’s important to notice now that the angle the tangent to the circle makes with the horizontal is the same as the angle the line from the bob to the centre makes with the vertical. The force on the bob at any moment is propor- tional to the sine of the angle at which the bob is currently moving. The net force is also directed perpendicular to the string, that is, in the instantaneous direction of motion. Because this force only changes the angle of the bob, and not the radius of the movement (a pendulum bob is always the same distance from its fixed point), we can write: θθ&& ∝sin Now, if θ is always small, which means the pendulum isn’t moving much, then sinθθ≈. This is very useful, as it lets us claim: θθ&& ∝ which tells us we have simple harmonic motion going on. -

Differential Geometry of Curves and Surfaces 1

DIFFERENTIAL GEOMETRY OF CURVES AND SURFACES 1. Curves in the Plane 1.1. Points, Vectors, and Their Coordinates. Points and vectors are fundamental objects in Geometry. The notion of point is intuitive and clear to everyone. The notion of vector is a bit more delicate. In fact, rather than saying what a vector is, we prefer to say what a vector has, namely: direction, sense, and length (or magnitude). It can be represented by an arrow, and the main idea is that two arrows represent the same vector if they have the same direction, sense, and length. An arrow representing a vector has a tail and a tip. From the (rough) definition above, we deduce that in order to represent (if you want, to draw) a given vector as an arrow, it is necessary and sufficient to prescribe its tail. a c b b a c a a b P Figure 1. We see four copies of the vector a, three of the vector b, and two of the vector c. We also see a point P . An important instrument in handling points, vectors, and (consequently) many other geometric objects is the Cartesian coordinate system in the plane. This consists of a point O, called the origin, and two perpendicular lines going through O, called coordinate axes. Each line has a positive direction, indicated by an arrow (see Figure 2). We denote by R the a P y a y x O O x Figure 2. The point P has coordinates x, y. The vector a has also coordinates x, y.