Table of Contents

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Out of the Past: a Walk with Labels and Concepts, Raiders of the Lost Evidence, and a Vindication of the Role of Writing'

lnternational Journal o? English Studies Out of the Past: A Walk with Labels and Concepts, Raiders of the Lost Evidence, and a Vindication of the Role of Writing' TR~NIDADGUZMAN-GONZALEZ* University of Leon «Im sorry to diroppoint science firtion fans, but if information ir preserved there ir no possibility of uring black holes to travel to o ther universes* (Stephen Hawkihg, Juh 21,2004) ABSTRACT 'Language' and 'change' have always been inextricably united in the minds of those who have paid attention to the former, for whatever purpose, from whatever perspective and from whatever discipline. The general opinion is that language cannot be understood without change. In its turn, change cannot be explained without a proper understanding of the complex, multidimensional nature of language a task which has constantly demanded the assistance of other fields of study. Among these, sociology and recent trends in evolutionary biology have introduced new and illuminating perspectives. What 1 intend to do in this basically review article is (a) delimit a number of concepts and keywords which very ofien tend to be used interchangeably; (b) pose a number of questions which to my mind would deserve consideration (ofien, reconsideration), with particular referente to the role of writing as a crucial dimension of the history of, among many others, English, the language which concerns me as a researcher; and (c) frarne rny discussion within the current theoretical models which have developed from the incorporation of the above mentioned fields to historical linguistics. KEYWORDS: language, change, evolution, historical/diachronic sociolinguistics, sociohistorical linguistics, social network, weak ties, writing. -

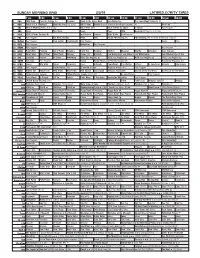

Sunday Morning Grid 2/3/19 Latimes.Com/Tv Times

SUNDAY MORNING GRID 2/3/19 LATIMES.COM/TV TIMES 7 am 7:30 8 am 8:30 9 am 9:30 10 am 10:30 11 am 11:30 12 pm 12:30 2 CBS CBS News Face the Nation (N) Pregame Road to the Super Bowl Tony Romo Sp. The Super Bowl Today (N) Å 4 NBC Today in L.A. Weekend Meet the Press (N) (TVG) NBC4 News Hockey Boston Bruins at Washington Capitals. (N) PGA Golf 5 CW KTLA 5 Morning News at 7 (N) Å KTLA News at 9 KTLA 5 News at 10am In Touch Paid Program 7 ABC News This Week News News NBA Basketball: Thunder at Celtics 9 KCAL KCAL 9 News Sunday (N) Joel Osteen Jentzen Mike Webb Paid Program 1 1 FOX Paid Program Fox News Sunday News PBC Inside PBC Boxing (N) PBA Bowling CP3 Celebrity Invitational. (Taped) 1 3 MyNet Paid Program Fred Jordan Freethought Paid Program News Paid 1 8 KSCI Paid Program Buddhism Paid Program 2 2 KWHY Paid Program Paid Program 2 4 KVCR Paint With Painting Joy of Paint Wyland’s Paint This Painting Kitchen Mexican Martha Christina Suze Orman’s 2 8 KCET Zula Patrol Zula Patrol Mixed Nutz Edisons Curios -ity Biz Kid$ Feel Better Fast and Make It Last With Daniel Joni Mitchell Live at Isle 3 0 ION Jeremiah Youseff In Touch Ankerberg NCIS: Los Angeles Å NCIS: Los Angeles Å NCIS: Los Angeles Å NCIS: Los Angeles Å 3 4 KMEX Conexión Paid Program Fútbol Fútbol Mexicano Primera División (N) República Deportiva (N) 4 0 KTBN James Win Walk Prince Carpenter Jesse In Touch PowerPoint It is Written Jeffress K. -

ESI Preservation 2010 Case Law Update Contents

ESI Preservation 2010 Case Law Update Contents TITLE PAGE & INTRODUCTION 1 THE THREE SEMINAL ESI CASES OF 2010 2 ADDITIONAL SELECTED CASES OF 2010 6 CONCLUSION 10 COMPLETE OPINIONS 11 OFFICE LocATIONS 551 1 2010 ESI Preservation Case Law Update uring the past decade the obligation to In selecting ESI-related opinions to address we have preserve electronically stored information deliberately steered away from many cases with (ESI) has continued to be shaped and defined egregious fact patterns where imposition of a severe Dby case law across the United States. 2010 sanction was never in doubt. The use of programs named was no different in this regard. For your review, we “File Shredder” and “Privacy Eraser Pro” to deliberately provide summaries of what we think were 2010’s most destroy ESI on the eve of an inspection makes for noteworthy cases in the area of ESI preservation. interesting reading.1 However, opinions pertaining to such behavior are not particularly instructive relative to You are likely already well-familiar with spoliation methods by which a litigant can comply with preservation in general and the sanctions a court can impose for obligations. Therefore, we have instead focused primarily a litigant’s failure to properly preserve evidence, on cases in which better preservation practices, policies including ESI. This letter focuses primarily on the and procedures at an organization-wide level could have obligations that arise, and the potential sanctions that prevented spoliation of ESI. can be imposed, once a reasonable anticipation of litigation (or an investigation) has triggered the duty For many potential litigants, ESI preservation issues are to preserve. -

IN the SUPREME COURT of the STATE of NEVADA the STATE of NEVADA, Appellant, V. PAUL LEWIS BROWNING, Respondent. Supreme Court No

IN THE SUPREME COURT OF THE STATE OF NEVADA THE STATE OF NEVADA, Supreme Court No. 78476 Appellant, District Court No. 85C72536 v. Capital Case PAUL LEWIS BROWNING, Respondent. RESPONDENT'S ANSWERING BRIEF Appeal from Grant of Motion to Dismiss Eighth Judicial District Court, Clark County Hon. Douglas Herndon STEVEN B. WOLFSON DANIEL J. ALBREGTS Clark County District Attorney Nevada Bar #004435 Nevada Bar #001565 601 S. 10th Street, Suite 202 Regional Justice Center Las Vegas, Nevada 89101 200 Lewis Avenue (702) 474-4004 Post Office Box 552212 Las Vegas, Nevada 89155-2212 IVETTE A. MANINGO (702) 671-2500 Nevada Bar #007076. 400 S. 4th Street, #500 AARON D. FORD Las Vegas, Nevada 89101 Nevada Attorney General (702) 793-4046 Nevada Bar No. 007704 100 North Carson Street TIMOTHY K. FORD Carson City, Nevada 89701-4717 Washington Bar #5986 (775) 684-1265 Pro hac vice pending MacDonald Hoague & Bayless Counsel for Appellant 705 2nd Avenue, #1500 State of Nevada Seattle, Washington 98104 (206) 622-1604 Counsel for Respondent Paul Lewis Browning NRAP 26.1 DISCLOSURE STATEMENT The undersigned counsel of record certifies that the following are persons and entities as described in NRAP 26.1(a), and must be disclosed. These representations are made in order that the judges of this Court may evaluate possible disqualification or recusal. Pretrial/Trial Proceedings Robert Amundson, Clark County Public Defender’s Office Randall H. Pike Christensen & Pike, Las Vegas Direct Appeal Brian Breedlove, Las Vegas John G. Watkins, Las Vegas Donald D. Beury Beury & Schubel, Las Vegas State Post Conviction Lee Elizabeth McMahon, Las Vegas William H. -

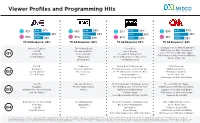

Viewer Profiles and Programming Hits

Viewer Profiles and Programming Hits 42% 18-34 27% 55% 18-34 28% 33% 18-34 28% 59% 18-34 34% 35-54 41% 35-54 39% 35-54 43% 35-54 38% 58% 45% 55-65+ 32% 55-65+ 33% 67% 55-65+ 28% 41% 55-65+ 28% TV Ad Response1 63% TV Ad Response1 60% TV Ad Response1 63% TV Ad Response1 64% America’s Top Dog The Walking Dead Below Deck The Situation Room With Wolf Blitzer Live PD Two and a Half Men Project Runway CNN Newsroom With Ana Cabrera State of the Union With Jake Tapper Alaska PD Better Call Saul Below Deck Sailing Yacht Q1 CNN Newsroom With Fredricka Whitfield Live PD: Wanted Talking Dead The Real Housewives of New Jersey Cuomo Prime Time Breaking Bad Vanderpump Rules Live PD Tombstone Below Deck Mediterranean CNN Newsroom Biography Two and a Half Men The Real Housewives of New York City CNN Newsroom Live Q2 Live PD: Wanted Better Call Saul The Real Housewives of Beverly Hills Erin Burnett OutFront Live PD: Rewind Movies Vanderpump Rules Cuomo Prime Time Below Deck Sailing Yacht CNN Newsroom With Ana Cabrera Live PD Two and a Half Men The Real Housewives Of Orange County The Lead With Jake Tapper Biography Fear the Walking Dead The Real Housewives of Beverly Hills CNN Newsroom With Brooke Baldwin Q3 Garth Brooks: The Road I’m On Movies Below Deck Mediterranean Situation Room With Wolf Blitzer Live PD: Wanted Southern Charm CNN Newsroom With Ana Cabrera The Real Housewives Of New York City Anderson Cooper 360 Garth Brooks: The Road I’m On The Walking Dead The Real Housewives of Orange County CNN Tonight With Don Lemon Court Cam Talking Dead Below Deck Mediterranean Cuomo Prime Time Q4 Live PD Movies Below Deck Anderson Cooper 360 Live PD: Wanted Project Runway Situation Room With Wolf Blitzer Watch What Happens Live With Andy Cohen CNN Newsroom With Brooke Baldwin 1 Percentage of network viewers that have seen/heard a TV ad in the last 12 months that has led them to take action as defined as clicking on a banner ad, doing an internet search, going to the advertisers website, buying the product advertised or calling/visiting the advertiser. -

Danger, Danger

FINAL-1 Sat, Apr 27, 2019 6:22:37 PM tvupdateYour Weekly Guide to TV Entertainment For the week of May 5 - 11, 2019 Emily Watson stars in “Chernobyl” INSIDE Danger, •Sports highlights Page 2 •TV Word Search Page 2 •Family Favorites Page 4 Hollywood Q&A Page14 danger • On Monday, May 6, join Soviet scientist Valery Legasov (Jared Harris, “The Terror”), nuclear physicist Ulana Khomyuk (Emily Watson, “Genius”) and head of the Bureau for Fuel and Energy of the Soviet Union Boris Shcherbina (Stellan Skarsgård, “River”), as they seek to uncover the truth behind one of the world’s worst man-made catastrophes in the premiere of “Chernobyl,” on HBO. WANTED WANTED MOTORCYCLES, SNOWMOBILES, OR ATVS To advertise here GOLD/DIAMONDS BUY SELL please call ✦ 40 years in business; A+ rating with the BBB. TRADE ✦ For the record, there is only one authentic CASH FOR GOLD, PARTS & ACCESSORIESBay 4 (978) 946-2375 Group Page Shell We Need: SALES & SERVICE Motorsports 5 x 3” Gold • Silver • Coins • Diamonds MASS. MOTORCYCLE1 x 3” We are the ORIGINAL and only AUTHENTIC INSPECTIONS CASH FOR GOLD on the Methuen line, above Enterprise Rent-A-Car 1615 SHAWSHEEN ST., TEWKSBURY, MA at 527 So. Broadway, Rte. 28, Salem, NH • 603-898-2580 978-851-3777 Open 7 Days A Week ~ www.cashforgoldinc.com WWW.BAY4MS.COM FINAL-1 Sat, Apr 27, 2019 6:22:38 PM COMCAST ADELPHIA 2 CHANNEL Kingston Sports Highlights Atkinson Londonderry 10:30 p.m. NESN Red Sox Final Live ESPN Softball NCAA ACC Tournament NESN Baseball MLB Seattle Mariners Salem Sunday Sandown Windham (60) TNT Basketball NBA Playoffs Live Women’s Championship Live at Boston Red Sox Live GUIDE Pelham, 10:55 a.m. -

Above and Beyond the Call of Duty Analyse Van De Voorstelling Van De

Universiteit Gent Academiejaar 2011 – 2012 Above and Beyond the Call of Duty Analyse van de voorstelling van de Tweede Wereldoorlog in first person shooter-games d.m.v. een ‘publiekshistorisch’ model Masterproef voorgelegd aan de Faculteit Letteren en Wijsbegeerte voor het behalen van de graad van ‘Master of Arts in de Geschiedenis’ op 10 augustus 2012 Door: Pieter Van den Heede (studentennummer: 00805755) Promotor: Prof. dr. G. Deneckere Commissarissen: A. Froeyman en F. Danniau Universiteit Gent Examencommissie Geschiedenis Academiejaar 2011-2012 Verklaring in verband met de toegankelijkheid van de scriptie Ondergetekende, ………………………………………………………………………………... afgestudeerd als master in de Geschiedenis aan Universiteit Gent in het academiejaar 2011- 2012 en auteur van de scriptie met als titel: ………………………………………………………………………………………………… ………………………………………………………………………………………………… ………………………………………………………………………………………………… ………………………………………………………………………………………………… ………………………………………………………………………………………………… verklaart hierbij dat zij/hij geopteerd heeft voor de hierna aangestipte mogelijkheid in verband met de consultatie van haar/zijn scriptie: o de scriptie mag steeds ter beschikking worden gesteld van elke aanvrager; o de scriptie mag enkel ter beschikking worden gesteld met uitdrukkelijke, schriftelijke goedkeuring van de auteur (maximumduur van deze beperking: 10 jaar); o de scriptie mag ter beschikking worden gesteld van een aanvrager na een wachttijd van … . jaar (maximum 10 jaar); o de scriptie mag nooit ter beschikking worden gesteld van een aanvrager (maximum- duur van het verbod: 10 jaar). Elke gebruiker is te allen tijde verplicht om, wanneer van deze scriptie gebruik wordt gemaakt in het kader van wetenschappelijke en andere publicaties, een correcte en volledige bronver- wijzing in de tekst op te nemen. Gent, ………………………………………(datum) ………………………………………(handtekening) VOORWOORD Graag wil ik de mensen bedanken die op één of andere manier hebben bijgedragen tot de realisatie van deze masterproef. -

Programming Highlights: July 29 – August 11 **

** PROGRAMMING HIGHLIGHTS: JULY 29 – AUGUST 11 ** NEW SERIES ‘STRANGE WORLD’ FOLLOWS AWARD-WINNING FILMMAKER CHRISTOPHER GERATANO AS HE INVESTIGATES AMERICA’S DEEPEST AND DARKEST CONSPIRACY THEORIES Wilderness Experts Chris and Casey Keefer Travel Through Uncharted Territory to Solve the World’s Greatest Mysteries in New Series ‘Code of the Wild’ *For photos and assets, please visit Travel Channel’s Press Website NEW SERIES PARANORMAL EMERGENCY Police officers, paramedics and other first responders reveal their true encounters with the paranormal while on duty. Not only do these cases defy explanation, they terrify even the most seasoned of men and women who have devoted their lives to serve and protect the living. SERIES PREMIERE: “It Wasn’t Human” – Premieres Monday, August 5 at 9 p.m. ET/PT An officer discovers a demon lurking around an abandoned factory, a paramedic is trapped inside a speeding ambulance with a poltergeist and a mysterious entity protects an officer during a shootout. CODE OF THE WILD Some of history’s greatest secrets are hidden in the world’s most treacherous corners, unforgiving locations that are inaccessible to all but a few. In Travel Channel’s all-new series, “Code of the Wild,” brothers Chris and Casey Keefer – extreme adventurers turned wilderness private eyes – tackle rugged territory that most wouldn’t dare, determined to track down the truth behind baffling mysteries. The brothers deploy their unique set of wilderness know-how, survival and tracking techniques, picking up where the trail for most would end, in search of answers that will finally put long- lost legends to rest. -

P32 Layout 1

32 Friday TV Listings Friday, November 1, 2019 03:45 Live PD: Police Patrol 21:35 Breaking Magic 20:15 Wheeler Dealers 11:30 UFO Hunters 04:10 Live PD: Police Patrol 22:00 Tricks On The Streets 21:00 Salvage Hunters: Classic 12:15 Battles BC 04:30 The First 48 22:25 Tricks On The Streets Cars 13:00 Modern Marvels 05:15 Homicide Hunter 22:50 Keeping Up With The Kruger 00:00 Sofia The First 21:50 Aaron Needs A Job 13:45 Serial Killer Earth 00:05 Crank 06:00 Homicide: Hours To Kill 23:40 Tanked 00:25 Disney Junior Music Nursery 22:40 Dirty Mudder Truckers 14:30 Clash Of The Gods 01:40 Leatherface 07:00 Live PD: Police Patrol Rhymes 23:30 Deadliest Catch 15:15 Ancient Aliens 03:15 Painted Skin: The Resurrec- 07:20 The First 48 00:30 Gigantosaurus 16:00 Deep Sea Salvage tion 08:05 The First 48 01:00 PJ Masks 16:45 UFO Hunters 05:35 Kung Fu Yoga 08:50 Homicide Hunter 01:25 PJ Masks 17:30 Battles BC 07:35 The Monkey King 09:35 Homicide Hunter 01:50 Paprika 18:15 America’s Book Of Secrets 09:40 The Taking Of Pelham 123 10:30 Homicide: Hours To Kill 00:00 True Nightmares 02:00 Zou 19:00 Search For The Lost Giants 11:40 Stargate 11:25 What The Killer Did Next 01:00 The Real Story With Maria 02:15 Zou 00:10 Randy Cunningham: 9th 19:45 Serial Killer Earth 13:45 Tai Chi 2: The Hero Rises 12:20 Crimes That Shook Britain Elena Salinas 02:30 Henry Hugglemonster Grade Ninja 20:30 Clash Of The Gods 15:40 American Ninja III 13:15 Live PD: Police Patrol 02:00 Deadline: Crime With Tam- 02:55 Henry Hugglemonster 01:00 Boyster 21:15 Ancient Aliens 17:25 Transformers: -

Highs and Lows

August 3 - 9, 2019 Highs and lows Zendaya stars in “Euphoria” AUTO HOME FLOOD LIFE WORK 101 E. Clinton St., Roseboro, N.C. 910-525-5222 [email protected] We ought to weigh well, what we can only once decide. SEE WHAT YOUR NEIGHBORS Complete Funeral Service including: Traditional Funerals, Cremation Pre-Need-Pre-Planning Independently Owned & Operated ARE TALKING ABOUT! Since 1920’s FURNITURE - APPLIANCES - FLOOR COVERING ELECTRONICS - OUTDOOR POWER EQUIPMENT 910-592-7077 Butler Funeral Home 401 W. Roseboro Street 2 locations to Hwy. 24 Windwood Dr. Roseboro, NC better serve you Stedman, NC www.clintonappliance.com 910-525-5138 910-223-7400 910-525-4337 (fax) 910-307-0353(fax) Page 2 — Saturday, August 3, 2019 — Sampson Independent On the Cover Generation Z(endaya): Freshman season of ‘Euphoria’ wraps up on HBO By Breanna Henry TV Media ue Bennett is a drug addict. RDespite having been recently released from a rehab center, she is not recovering, and does not in- tend to remain clean. She routine- ly meets strangers online for “hook-ups,” browses sketchy websites, and lies about her age. Rue is only 17-years-old, and luckily for her parents, she is a fic- tional character from the premium cable show “Euphoria,” played by Disney Channel graduate Zendaya (“Spider-Man: Far From Home,” 2019). If you haven’t been keep- ing up with “Euphoria” so far, you can stream previous episodes on HBO Go, and the Season 1 finale (titled “And Salt the Earth Behind You”) airs Sunday, Aug. 4, on HBO. The fantastic cast of fresh young actors “Euphoria” revolves around includes Jacob Elordi (“The Kissing Booth,” 2018) as angry, confused jock Nate; Algee Smith (“The Hate U Give,” 2018) as struggling college athlete Chris; Barbie Ferreira (“Divorce”) as insecure, sexually curious Kat; Sydney Sweeney (“Sharp Ob- jects”) as Cassie, who can’t seem to escape her past; and the show’s breakout star, trans runway model Hunter Schafer in her first role as Jules, a transgender teen girl look- ing to find the place she belongs. -

Star Channels Guide, Oct. 29-Nov. 4

OCTOBER 29 - NOVEMBER 4, 2017 staradvertiser.com HOLEY HUMOR Arthur (Judd Hirsch) and Franco (Jermaine Fowler) prepare to take on gentrifi cation, corporations and trendy food trucks in the humorously delicious sophomore season of Superior Donuts. Premieres Monday, Oct. 30, on CBS. Join host, Lyla Berg as she sits down with guests Meet the NEW SHOW WEDNESDAY! who share their work on moving our community forward. people SPECIAL GUESTS INCLUDE: and places Nate Gyotoku, Director of Sustainability Initiatives, KUPU that make Jerri Chong, President, Ronald McDonald House Charities of Hawaii 1st & 3rd Wednesday Desoto Brown, Historian, Bishop Museum Hawai‘i olelo.org of the Month, 6:30 pm Shari Chang, CEO of Girl Scouts of Hawaii Channel 53 special. Representative Jarrett Keohokalole ON THE COVER | SUPERIOR DONUTS Tasty yet topical Deliciously real laughs in alongside the shop as it continues to draw new customers with healthier breakfast alterna- faces in, while never losing sight of its regulars. tives, keeping in mind social and ethical prin- season 2 of ‘Superior Donuts’ The quick wit and bold approach to dis- ciples. The discussions surrounding millennials cussing modern issues make it unsurprising aren’t new for “Superior Donuts,” but the ad- By Kat Mulligan that the series is back for a second season. dition of Sofia provides yet another outlet for TV Media “Superior Donuts” never shies away from Arthur’s reluctance to change, as her healthy confronting topics such as gentrification, the alternatives food truck threatens to take away ong before the trends of grandes, mac- corporation creep into small neighborhoods some of the fresh clientele Franco and Arthur chiatos and pumpkin spice lattes, neigh- and the death of the small business owner. -

Adverse Possession and Takings Seldom Compensate for Chance

ADVERSE POSSESSION AND TAKINGS SELDOM COMPENSATION FOR CHANCE HAPPENINGS Martin J. Foncello∗ INTRODUCTION The law of adverse possession is relatively settled.1 Generally, a trespasser’s possession of another’s property will result in a transfer of title if the possession was adverse, exclusive, open and notorious, and uninterrupted for the statutory period.2 By failing to assert the right to exclude within the statutory period, the true owner loses title to the property3 and is without claim for compensation or damages.4 Federal takings law, on the other hand, is relatively unsettled.5 While the Fifth Amendment’s requirement that the government must pay just compensation for any land taken for public purpose is straightforward, it has proven difficult in application.6 The Takings ∗ J.D. Candidate, 2005, Seton Hall University School of Law; B.A., 2000, Boston College. The author would like to thank Professors Marc Poirier and Jeremy Blumenthal for their criticism, encouragement, and friendship. 1 Thomas W. Merrill, Property Rules, Liability Rules, and Adverse Possession, 79 NW. U. L. REV. 1122, 1122 (1984) (“The law of adverse possession tends to be regarded as a quiet backwater.”). 2 Classic legal scholarship on adverse possession is in agreement on the elements necessary to make out a claim. See Henry W. Ballantine, Title by Adverse Possession, 32 HARV. L. REV. 135 (1918); Henry W. Ballantine, Claim of Title in Adverse Possession, 28 YALE L.J. 219 (1918); Percy Bordwell, Mistake and Adverse Possession, 7 IOWA L. BULL. 129 (1922); William Edwin Taylor, Actual Possession in Adverse Possession of Land, 25 IOWA L.