Fundamental Rights in the Realm of New Zealand: Theory and Practice

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Niue Constitution

157 PACIFIC CONSTITUTIONS – OVERVIEW Ces deux articles présentent les règles constitutionnelles aujourd’hui en vigueur à Niue et à Tokelau, leurs fonctions et leurs principales conditions de mise en œuvre. The following papers give a law introduction to the constitutions of Niue and Tokelau and provide a current overview of their role and key provisions. THE NIUE CONSTITUTION A H Angelo* The Constitution of Niue is neat and technically may be the best of all the constitutions of the South Pacific countries. The Constitution's origins are in an Act of the New Zealand Parliament1 but, following constitutional convention and the traditional Common Law model,2 the country is autonomous. I INTRODUCTION A History The Constitution of Niue has evolved out of early New Zealand colonial statutes. The first was the Cook and Other Islands Government Act of 1901 and subsequently, * Professor of Law, Victoria University of Wellington, New Zealand. This paper is a chapter originally prepared as a contribution for a book on constitutional evolution in the Pacific. 1 Niue Constitution Act 1974. 2 The independence constitutions of most countries in the region were law of the United Kingdom eg Australia (the Commonwealth of Australia Constitution Act 1900), New Zealand (New Zealand Constitution Act 1854), Solomon Islands (Solomon Islands Order in Council SO&I 1978/783). 158 (2009) 15 REVUE JURIDIQUE POLYNÉSIENNE just prior to the self-determination of the Cook Islands, a Cook Islands Amendment Act was promulgated which effectively severed Niue from the territory of the Cook Islands.3 The early statutes4 provided a code of laws for Niue. -

Governance and Culture: Whether Niue Should Develop Law and Policy

139 GOVERNANCE AND CULTURE: SHOULD NIUE DEVELOP LAW AND POLICY FOR AN OMBUDSMAN SERVICE? K Sinahemana Hekau∗ This paper considers the possibility of establishing the office of Ombudsman in Niue. This is an edited version of a paper presented at the 11th Pacific Science Inter Congress held in Tahiti in March 2009. Cet article envisage les conditions de la mise en place d’un Ombudsman à Niue. Les développements qui suivent, représentent la version complétée d'une présentation faite lors du 11e Inter-congrès des Sciences du Pacifique qui s’est tenu à Tahiti en mars 2009. Thirty-five years into self-government, Niue has been invited to follow its Forum1 peers and establish an Ombudsman service. Under ∗ LLM (VUW); Barrister and Solicitor of the High Court of Niue. The assistance of the Alliance Française, the Government of Niue, and the Pacific Ombudsman Alliance for the preparation of this paper is gratefully acknowledged. 1 Pacific Islands Forum members are; Australia, Cook Islands, Federated States of Micronesia, Fiji, Kiribati, New Zealand, Niue, Palau, Papua New Guinea, Republic of the Marshall Islands, Samoa, Solomon Islands, Tonga, Tuvalu and Vanuatu. 140 GOUVERNANCE DANS LE PACIFIQUE SUD the Forum's Pacific Plan, good governance is featured as one of the key pillars for achieving the Pacific Leaders vision:2 Leaders believe the Pacific region can, should and will be a region of peace, harmony, security and economic prosperity, so that all its people can lead free and worthwhile lives. We treasure the diversity of the Pacific and seek a future in which its cultures, traditions and religious beliefs are valued, honoured and developed. -

Perhaps One Framework That Could Have Been Explored As a Possible Theme of the Book Was the Differences in Strategy Employed by Various National-Based IWW Unions

REVIEWS (BOOKS) 167 Perhaps one framework that could have been explored as a possible theme of the book was the differences in strategy employed by various national-based IWW unions. For example, a major contrast existed between the US IWW, with its ‘dual unionist’ strategy (meaning it set up a new militant industrial union in opposition to conservative, craft-based unions), and the IWW in Australasia, where, as Verity Burgmann details in her chapter about the Australian IWW, Wobblies aimed to ‘bore from within’ existing unions and union federations, such as the ‘Red Feds’ (the first Federation of Labour in Aotearoa New Zealand), and actually had some success. Further, in seeking to overcome the IWW’s marginalization by historians globally – including in this country – the book sometimes veers towards over-inflating the IWW’s influence. For example, the editors’ claim that ‘the IWW reached almost every corner of the globe’ (p.8) seems exaggerated given the IWW’s negligible presence in Africa and Asia, and its sporadic influence in Europe and South America (apart from perhaps Chile and Argentina, which are not covered in the book). Wobblies of the World is a welcome addition to studies of the IWW and syndicalism globally and in Aotearoa New Zealand. It covers a broad range of countries, uses multi-lingual sources innovatively, and attempts to overcome the academic–activist divide. Yet overall these innovations are unfortunately let down by its narrative- based chapters that overall lack in-depth critical analysis. Very good, and sometimes excellent, chapters about the French influence over the IWW, and the IWW influence in Australasia, Mexico, Sweden and South Africa (among others) sit uneasily alongside chapters which are little more than fragmentary snippets and biographical vignettes. -

A Governor-General's Perspective

THE ARCHITECTURE OF ELECTIONS IN NEW ZEALAND: A GOVERNOR-GENERAL’S PERSPECTIVE BY RT HON SIR ANAND SATYANAND, GNZM, QSO* I. INTRODUCTION I begin by greeting everyone in the languages of the realm of New Zealand, in English, Mäori, Cook Island Mäori, Niuean, Tokelauan and New Zealand Sign Language. Greetings, Kia Ora, Kia Orana, Fakalofa Lahi Atu, Taloha Ni and as it is the morning (Sign). I then specifically greet you: Rt Hon Jim Bolger, Chancellor of the University of Waikato; Professor Roy Crawford, Vice-Chancellor; Professor Bradford Morse, Dean of Te Piringa – Fac- ulty of Law; Distinguished Guests otherwise; Ladies and Gentlemen. Thank you for the invitation to give this public lecture for the Faculty of Law. Before beginning, I want to welcome you, Professor Morse, in your new role as Dean of Uni- versity of Waikato’s Faculty of Law. With your previous experience at the University of Ottawa in Canada and your considerable scholarship in indigenous law in Canada, you bring to New Zea- land a valuable perspective on our country, on particular issues relating to Mäoridom.1 I wish you well in your role. You join the University at a time when it has come of age – and is celebrating the 20th anniver- sary of the establishment of the Faculty. You will find that the University and this Faculty has a strong and rewarding connection with the Waikato-Tainui iwi. I understand the Faculty’s Mäori name, Te Piringa, was provided by the late Arikinui Dame Te Atairangikaahu, the then Mäori Queen. Translated as “the coming together of people”, it links the Faculty to the manawhenua of Waikato-Tainui. -

Perspectives on a Pacific Partnership

The United States and New Zealand: Perspectives on a Pacific Partnership Prepared by Bruce Robert Vaughn, PhD With funding from the sponsors of the Ian Axford (New Zealand) Fellowships in Public Policy August 2012 Established by the Level 8, 120 Featherston Street Telephone +64 4 472 2065 New Zealand government in 1995 PO Box 3465 Facsimile +64 4 499 5364 to facilitate public policy dialogue Wellington 6140 E-mail [email protected] between New Zealand and New Zealand www.fulbright.org.nz the United States of America © Bruce Robert Vaughn 2012 Published by Fulbright New Zealand, August 2012 The opinions and views expressed in this paper are the personal views of the author and do not represent in whole or part the opinions of Fulbright New Zealand or any New Zealand government agency. Nor do they represent the views of the Congressional Research Service or any US government agency. ISBN 978-1-877502-38-5 (print) ISBN 978-1-877502-39-2 (PDF) Ian Axford (New Zealand) Fellowships in Public Policy Established by the New Zealand Government in 1995 to reinforce links between New Zealand and the US, Ian Axford (New Zealand) Fellowships in Public Policy provide the opportunity for outstanding mid-career professionals from the United States of America to gain firsthand knowledge of public policy in New Zealand, including economic, social and political reforms and management of the government sector. The Ian Axford (New Zealand) Fellowships in Public Policy were named in honour of Sir Ian Axford, an eminent New Zealand astrophysicist and space scientist who served as patron of the fellowship programme until his death in March 2010. -

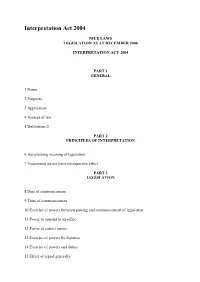

Interpretation Act 2004

Interpretation Act 2004 NIUE LAWS LEGISLATION AS AT DECEMBER 2006 INTERPRETATION ACT 2004 PART 1 GENERAL 1 Name 2 Purposes 3 Application 4 Sources of law 5 Definitions 0 PART 2 PRINCIPLES OF INTERPRETATION 6 Ascertaining meaning of legislation 7 Enactments do not have retrospective effect PART 3 LEGISLATION 8 Date of commencement 9 Time of commencement 10 Exercise of powers between passing and commencement of legislation 11 Power to appoint to an office 12 Power to correct errors 13 Exercise of powers by deputies 14 Exercise of powers and duties 15 Effect of repeal generally 16 Effect of repeal on enforcement of existing rights 17 Effect of repeal on prior offences and breaches of enactments 18 Enactments made under repealed legislation to have continuing effect 19 Powers exercised under the repealed legislation to have continuing effect 20 References to repealed enactment 21 Amending enactment part of enactment 22 Regulations 23 Power to make regulations 24. Enactments not binding on the Government PART 4 MISCELLANEOUS 25 Use of forms 26 Bodies corporate 27 Parts of speech and grammatical forms 28 Number 29 Calendar and standard time 30 Calculation of time 31 Distances 32 Thumbprint or mark in lieu of signature 33 Electronically recorded documents 34 Currency 35 Publication 36-37 [Spent] _____________________________ Relating to the interpretation, application, and effect of legislation and public documents PART 1 GENERAL 1 Name This is the Interpretation Act 2004. 2 Purposes The purposes of this Act are— (a) To state principles and rules for the interpretation of legislation and public documents; (b) To shorten legislation and public documents; and (c) To promote consistency in the language and form of legislation and public documents. -

New Impulses in the Interaction of Law and Religion: a South Pacific Perspective

BYU Law Review Volume 2003 | Issue 2 Article 6 5-1-2003 New Impulses in the Interaction of Law and Religion: A South Pacific eP rspective Don Paterson Follow this and additional works at: https://digitalcommons.law.byu.edu/lawreview Part of the Comparative and Foreign Law Commons, Human Rights Law Commons, and the Religion Law Commons Recommended Citation Don Paterson, New Impulses in the Interaction of Law and Religion: A South Pacific erP spective, 2003 BYU L. Rev. 593 (2003). Available at: https://digitalcommons.law.byu.edu/lawreview/vol2003/iss2/6 This Article is brought to you for free and open access by the Brigham Young University Law Review at BYU Law Digital Commons. It has been accepted for inclusion in BYU Law Review by an authorized editor of BYU Law Digital Commons. For more information, please contact [email protected]. PAT-FIN 5/31/2003 1:23 PM New Impulses in the Interaction of Law and Religion: A South Pacific Perspective Don Paterson∗ I. INTRODUCTION This article will look at the way in which new religions were introduced first from Britain and Europe and then later from the United States of America into all island countries of the South Pacific during the nineteenth century. The next part will examine the extent to which the laws of those countries provide freedom of religion and it will then consider certain legal and sociological limitations upon the actual practice of religion in these same countries. The article will conclude by looking to the future and trying to suggest ways to ease the tension that exists between individual freedom to practice the religion of his or her choice and community concern for preserving peace and harmony in the community. -

Passage of Change

PASSAGE OF CHANGE PASSAGE OF CHANGE LAW, SOCIETY AND GOVERNANCE IN THE PACIFIC edited by Anita Jowitt and Dr Tess Newton Cain Published by ANU E Press The Australian National University Canberra ACT 0200, Australia Email: [email protected] This title is also available online at: http://epress.anu.edu.au/passage_change _citation.html National Library of Australia Cataloguing-in-Publication Entry Title: Passage of change : law, society and governance in the Pacific / edited by Anita Jowitt and Tess Newton Cain. ISBN: 9781921666889 (pbk.) 9781921666896 (eBook) Notes: Includes bibliographical references. Subjects: Jurisprudence--Pacific Area. Customary law--Pacific Area. Pacific Area--Politics and government. Pacific Area--Social conditions. Other Authors/Contributors: Jowitt, Anita. Cain, Tess Newton. Dewey Number: 340.5295 All rights reserved. No part of this publication may be reproduced, stored in a retrieval system or transmitted in any form or by any means, electronic, mechanical, photocopying or otherwise, without the prior permission of the publisher. Cover design by Emily Brissenden Printed by Griffin Press This edition © 2010 ANU E Press First edition © 2003 Pandanus Books CONTENTS Acknowledgments vii Table of Abbreviations viii Table of Cases x Table of International Conventions xiii Table of Legislation xiv Notes on Contributors xvii INTRODUCTION Anita Jowitt and Tess Newton-Cain 1 SECTION 1: THE CONTEXT OF CHANGE 1. Modernisation and Development in the South Pacific Vijay Naidu 7 SECTION 2: CORRUPTION 2. Corruption Robert Hughes 35 3. Governance, Legitimacy and the Rule of Law in the South Pacific Graham Hassall 51 4. The Vanuatu Ombudsman Edward R. Hill 71 SECTION 3: CUSTOMARY LAW 5. -

Niue Amendment Act (No 2) 1968

20070920 Niue Amendment Act (No 2) 1968 Public Act 1968 No 132 Date of assent 17 December 1968 Contents Page Title 5 1 Short Title and commencement 5 2 Interpretation [Repealed] 5 Part 1 Land tenure [Repealed] 3 Classification of land in Niue [Repealed] 5 4 All land in Niue vested in the Crown [Repealed] 5 5 Foreshore and seabed vested in the Crown [Repealed] 5 6 Administration and tenure of land [Repealed] 6 7 Saving of existing interests in Niuean land [Repealed] 6 Part 2 Crown land [Repealed] 8 Grants of Crown land [Repealed] 6 9 Crown land may be declared Niuean land [Repealed] 6 10 Reserves of Crown land for public purposes [Repealed] 6 11 Taking of land for public purposes [Repealed] 6 12 Revocation of Warrant taking land [Repealed] 7 13 Compensation for land taken [Repealed] 7 14 Resumption of Crown land for public purposes [Repealed] 7 16 Acquisition of land for public purposes [Repealed] 7 1 Niue Amendment Act (No 2) 1968 1968 No 132 17 Public purpose for which land held may be 7 altered [Repealed] 18 Control of Crown land by Cabinet of Ministers [Repealed] 7 19 Saving of reserves under the Cook Islands Government 7 Act 1908 [Repealed] 20 Power to revoke or amend existing Orders in 8 Council [Repealed] Part 3 Niuean land [Repealed] 21 Ownership in Niuean land [Repealed] 8 22 Investigation of title to Niuean land [Repealed] 8 23 Niuean customs to be recognised [Repealed] 8 24 No alienation of Niuean land [Repealed] 8 25 For certain purposes Niuean land to be deemed Crown 8 land [Repealed] Part 4 Land for Church purposes [Repealed] -

Exploring 'The Rock': Material Culture from Niue Island in Te Papa's Pacific Cultures Collection; from Tuhinga 22, 2011

Tuhinga 22: 101–124 Copyright © Museum of New Zealand Te Papa Tongarewa (2011) Exploring ‘the Rock’: Material culture from Niue Island in Te Papa’s Pacific Cultures collection Safua Akeli* and Shane Pasene** * Museum of New Zealand Te Papa Tongarewa, PO Box 467, Wellington, New Zealand ([email protected]) ** Museum of New Zealand Te Papa Tongarewa, PO Box 467, Wellington, New Zealand ([email protected]) ABSTRACT: The Pacific Cultures collection of the Museum of New Zealand Te Papa Tongarewa (Te Papa) holds around 300 objects from the island of Niue, including textiles, costumes and accessories, weapons, canoes and items of fishing equipment. The history of the collection is described, including the increasing involvement of the Niue community since the 1980s, key items are highlighted, and collecting possibilities for the future are considered. KEYWORDS: Niue, material culture, collection history, collection development, community involvement, Te Papa. Introduction (2010). Here, we take the opportunity to document and publish some of the rich and untold stories resulting from the The Pacific Cultures collection of the Museum of New Niue collection survey, offering a new resource for researchers Zealand Te Papa Tongarewa (Te Papa) comprises objects and the wider Pacific community. from island groups extending from Hawai‘i in the north to The Niue collection comprises 291 objects. The survey Aotearoa/New Zealand in the south, and from Rapanui in has revealed an interesting history of collecting and provided the east to Papua New Guinea in the west. The geographic insight into the range of objects that make up Niue’s material coverage is immense and, since the opening of the Colonial culture. -

The New Zealand Model of Free Association: What Does It Mean for New Zealand?

607 THE NEW ZEALAND MODEL OF FREE ASSOCIATION: WHAT DOES IT MEAN FOR NEW ZEALAND? Alison Quentin-Baxter* Using Professor Angelo's work in Tokelau as a starting point, Alison Quentin-Baxter examines the model of "free association" relationship that New Zealand has with the Cook Islands and with Niue, and was also to be the basis of Tokelauan self-government. She looks at both the legal and practical obligations that such relationships place on both parties, but particularly on New Zealand. The form of the model means the basis for New Zealand's obligations to an associated state are quite different from its provision of aid to other states. I INTRODUCTION It is an honour and a pleasure to contribute to this Special Issue of the VUW Law Review celebrating Professor Tony Angelo's 40 years as a leading member of the teaching staff of the Law Faculty. For the whole of that period he and I have been colleagues and friends. Reflecting our shared interests, my topic is New Zealand's role as a partner in the relationships of free association with the self-governing States of the Cook Islands and of Niue, and potentially a self-governing State of Tokelau, if it, too, should decide to move to a similar status and relationship with New Zealand. The free association with the Cook Islands has been in place since 1965, and that with Niue since 1974. Twice in the last three years, the people of Tokelau have hesitated on the brink of a similar relationship. Now, as they pause to catch their breath, it seems a good time to look at the New Zealand model of free association from the standpoint of this country's own constitutional law, as distinct from international law or the constitutional law of the associated State. -

Volume 1.Pdf

NIUE LAWS TAU FAKATUFONO-TOHI A NIUE LEGISLATION AS AT DECEMBER 2006 VOLUME 1 TOHI 1 CONSTITUTION STATUTES A – COMPANIES GOVERNMENT OF NIUE, ALOFI 2006 Copyright 2006 All rights reserved Enquiries concerning the copyright material should be addressed to the Crown Law Office, Alofi, Niue Compiled in the Faculty of Law, Victoria University of Wellington by Professor AH Angelo with the assistance of Nicola Scott Printed by Stylex Print, Palmerston North, New Zealand Niue Laws 2006 Vol 1 iv CONTENTS Foreword ................................................................................................................ iii Editorial Note ........................................................................................................ xi VOLUME ONE PART 1 – LEGISLATION TABLES Table of Constitutional Instruments .................................................................. xv Table of Acts in Force ........................................................................................... xvii Chronological Table of Statutes .......................................................................... xxxi Table of Subsidiary Legislation in Force............................................................ xlv Chronological Table of Subsidiary Legislation................................................. lv CONSTITUTIONAL INSTRUMENTS Constitution of Niue............................................................................................. 1 Ko e Fakatufono-Tohi Fakave A Niue ...............................................................