85Th, Miami, Florida, August 5-8, 2002)

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Reginald Howard

20080618_Howard Page 1 of 14 Dara Chesnutt, Denzel Young, Reginald Howard Dara Chesnutt: Appreciate it. Could you start by saying your full name and occupation? Reginald Howard: Reginald R. Howard. I’m a real estate broker and real estate appraiser. Dara Chesnutt: Okay. Where were you born and raised? Reginald Howard: South Bend, Indiana, raised in Indiana, also, born and raised in South Bend. Dara: Where did you grow up and did you move at all or did you stay mostly in –? Reginald Howard: No. I stayed mostly in Indiana. Dara Chesnutt: Okay. What are the names of your parents and their occupations? Reginald Howard: My mother was a housewife and she worked for my father. My father’s name was Adolph and he was a tailor and he had a dry cleaners, so we grew up sorta privileged little black kids. Even though we didn’t have money, people thought we did for some reason. Dara Chesnutt: Did you have any brothers or sisters? Reginald Howard: Sure. Dara Chesnutt: Okay, what are their names and occupations? Reginald Howard: I had a brother named Carlton, who is deceased. [00:01:01] I have a brother named Dean, who’s my youngest brother, who’s just retired from teaching in Tucson, Arizona and I have a sister named Alfreda who’s retired and lives in South Bend still. Dara Chesnutt: Okay. Could you talk a little bit about what your home life was like? Reginald Howard: I don’t know. I had a very strong father and very knowledgeable father. We were raised in a predominantly Hungarian-Polish neighborhood and he – again, he had a business and during that era, it was the area of neighborhood concept businesses and so people came to us for service, came to him for the service, and he was well thought of. -

Download The

1 February 15, 2017 Chris Cox, Director of Marketing and Communications Office: (412) 281-0912, ext. 217 Cell: (412) 427-7088 [email protected] Pittsburgh Opera presents the world premiere of The Summer King – the Josh Gibson Story What: World premiere of Daniel Sonenberg’s The Summer King – The Josh Gibson Story. Libretto by Daniel Sonenberg and Daniel Nester, with additional lyrics by Mark Campbell. Where: Benedum Center for the Performing Arts, 237 7th Street, Pittsburgh When: Sat, Apr 29, 2017 * 8:00 PM Tue, May 2, 2017 * 7:00 PM Fri, May 5, 2017 * 7:30 PM Sun, May 7, 2017 * 3:00 PM ALSO: Thursday, May 4th: Student Matinee performance at 10:30 AM Run Time: 2 hours, 12 minutes, including two intermissions Language: Sung in English with English texts projected above the stage Tickets: Tickets start at just $12. Group Discounts available. Call 412-456-6666 for more information or visit pittsburghopera.org/tickets. Media Events Please contact [email protected] for reservations Photo Call (Monday, April 10th , 12:30 PM) – location TBD Full Dress Rehearsal (Thursday, April 27th, 7:00 PM), Benedum Related Events Community Engagement events (February and April) Brown Bag Concert (April 1st) See pages 8- Opera Up Close (April 9th) 11 of this WQED Preview (April 22nd & 28th) release. “Creating an Opera” (April 23rd) Meet the Artists (May 2nd) Audio Commentary (May 2nd) 2425 Liberty Avenue Pittsburgh, PA 15222 www.pittsburghopera.org 2 The Summer King – the Josh Gibson Story World Premiere by Daniel Sonenberg Libretto by Daniel Sonenberg and Daniel Nester, with additional lyrics by Mark Campbell Based on the life of baseball Hall of Famer Josh Gibson Sung in English with English texts projected above the stage Concept Drawing of staging by Andrew Lieberman Pittsburgh, PA Pittsburgh Opera’s 2016-17 season concludes with the first world premiere in our illustrious 78-year history. -

California Golden Bears 2021 Track & Field Record Book 1

CALIFORNIA GOLDEN BEARS 2021 TRACK & FIELD RECORD BOOK 1 2021 CALIFORNIA TRACK & FIELD 2021 SCHEDULE QUICK FACTS Date Day Meet Site Name ............... University of California January Location ....................... Berkeley, Calif. 22-23 Fri.-Sat. at Air Force Invitational Colorado Springs, Colo. Founded ...................................... 1868 February Enrollment ................................ 40,173 19 Fri. at Air Force Collegiate Open Colorado Springs, Colo. Nickname ...................... Golden Bears 25-27 Thu.-Sat. at Championships at the Peak Colorado Springs, Colo. Colors ............ Blue (282) & Gold (123) Chancellor ........................ Carol Christ March Director of Athletics ... ....Jim Knowlton 6 Sat. California Outdoor Opener Berkeley, Calif. Home Facility ........... Edwards Stadium 11-13 Fri.-Sat. at NCAA Indoor Championships Fayetteville, Ark. (22,000) 20 Sat. at USC Dual Los Angeles, Calif. 2020 Men’s Finishes (indoor): 26-27 Fri.-Sat. at Aztec Invitational San Diego, Calif. MPSF/NCAA ........................N/A/N/A 2020 Men’s Finishes (outdoor): April Pac-12/NCAA ......................N/A/N/A 3 Sat. at Stanford Invitational Stanford, Calif. 2020 Women’s Finishes (indoor): 10 Sat. USC Dual Berkeley, Calif. MPSF/NCAA ........................N/A/N/A 2020 Women’s Finishes (outdoor): May Pac-12/NCAA ......................N/A/N/A 1 Sat. Big Meet Berkeley, Calif. 14-16 Fri.-Sun. at Pac-12 Outdoor Championships Los Angeles, Calif. ATHLETIC COMMUNICATIONS 27-29 Thu.-Sat. at NCAA West Preliminary Rounds College Station, -

Race Handout 02 Debate V7

Race Lesson Plan Handout #2 Handout #2: Debate In 1945, only 4% of American businesses were owned by African Americans. However, the owners of the Negro Leagues teams in the same period were almost entirely African American. Many have argued that the Negro Leagues provided a rare avenue for Black entrepreneurs to achieve financial success. For decades, the owners of Major League Baseball honored a policy referred to as the “Gentlemen’s Agreement.” The “Gentlemen’s Agreement” was an unwritten pact between all of the owners holding that none of them would sign African American ballplayers to Major League teams. For decades, when the issue of segregation was brought up, the owners would claim that if they were to scout a Black ballplayer who could compete in their league they would happily sign him. This was obviously not true. “These Negro associations give men like me a puncher’s chance. White baseball be damned.” – Andrew “Rube” Foster, Negro Leagues Executive Rube Foster Page 1 Race Lesson Plan Handout #2 “They [MLB owners], used to say, ‘If we find a good Black player, we’ll sign him.’ They was lying.” – Cool Papa Bell Cool Papa Bell “I can’t own a restaurant that white people will eat in. I can’t sell no clothes that white people will wear, but we know white people gonna show up on Sunday to see these Crawfords play.” – Gus Greenlee, Owner of the Pittsburgh Crawfords Gus Greenlee Page 2 Race Lesson Plan Handout #2 “The only change [in joining the Negro Leagues] is that baseball has turned me from a second class citizen to a second class immortal.” – Satchel Paige Satchel Paige “Baseball was in some ways a realm of freedom for Black Americans. -

The Philadelphia Stars, 1933-1953

Lehigh University Lehigh Preserve Theses and Dissertations 2002 A faded memory : The hiP ladelphia Stars, 1933-1953 Courtney Michelle Smith Lehigh University Follow this and additional works at: http://preserve.lehigh.edu/etd Recommended Citation Smith, Courtney Michelle, "A faded memory : The hiP ladelphia Stars, 1933-1953" (2002). Theses and Dissertations. Paper 743. This Thesis is brought to you for free and open access by Lehigh Preserve. It has been accepted for inclusion in Theses and Dissertations by an authorized administrator of Lehigh Preserve. For more information, please contact [email protected]. Smith, Courtney .. Michelle A Faded Memory: The Philadelphia . Stars, 1933-1953 June 2002 A Faded Memory: The Philadelphia Stars, 1933-1953 by Courtney Michelle Smith A Thesis Presentedto the Graduate and Research Committee ofLehigh University in Candidacy for the Degree of Master ofArts m the History Department Lehigh University May 2002 Table of Contents Chapter-----' Abstract, '.. 1 Introduction 3 1. Hilldale and the Early Years, 1933-1934 7 2. Decline, 1935-1941 28 3. War, 1942-1945 46 4. Twilight Time, 1946-1953 63 Conclusion 77 Bibliography ........................................... .. 82 Vita ' 84 iii Abstract In 1933, "Ed Bolden and Ed Gottlieb organized the Philadelphia Stars, a black professional baseball team that operated as part ofthe Negro National League from 1934 until 1948. For their first two seasons, the Stars amassed a loyal following through .J. regular advertisements in the Philadelphia Tribune and represented one of the Northeast's best black professional teams. Beginning in 1935, however, the Stars endured a series of losing seasons and reflected the struggles ofblack teams to compete in a depressed economic atmosphere. -

BRONZO 2016 Usain Bolt

OLIMPIADI L'Albo d'Oro delle Olimpiadi Atletica Leggera UOMINI 100 METRI ANNO ORO - ARGENTO - BRONZO 2016 Usain Bolt (JAM), Justin Gatlin (USA), Andre De Grasse (CAN) 2012 Usain Bolt (JAM), Yohan Blake (JAM), Justin Gatlin (USA) 2008 Usain Bolt (JAM), Richard Thompson (TRI), Walter Dix (USA) 2004 Justin Gatlin (USA), Francis Obikwelu (POR), Maurice Greene (USA) 2000 Maurice Greene (USA), Ato Boldon (TRI), Obadele Thompson (BAR) 1996 Donovan Bailey (CAN), Frank Fredericks (NAM), Ato Boldon (TRI) 1992 Linford Christie (GBR), Frank Fredericks (NAM), Dennis Mitchell (USA) 1988 Carl Lewis (USA), Linford Christie (GBR), Calvin Smith (USA) 1984 Carl Lewis (USA), Sam Graddy (USA), Ben Johnson (CAN) 1980 Allan Wells (GBR), Silvio Leonard (CUB), Petar Petrov (BUL) 1976 Hasely Crawford (TRI), Don Quarrie (JAM), Valery Borzov (URS) 1972 Valery Borzov (URS), Robert Taylor (USA), Lennox Miller (JAM) 1968 James Hines (USA), Lennox Miller (JAM), Charles Greene (USA) 1964 Bob Hayes (USA), Enrique Figuerola (CUB), Harry Jeromé (CAN) 1960 Armin Hary (GER), Dave Sime (USA), Peter Radford (GBR) 1956 Bobby-Joe Morrow (USA), Thane Baker (USA), Hector Hogan (AUS) 1952 Lindy Remigino (USA), Herb McKenley (JAM), Emmanuel McDonald Bailey (GBR) 1948 Harrison Dillard (USA), Norwood Ewell (USA), Lloyd LaBeach (PAN) 1936 Jesse Owens (USA), Ralph Metcalfe (USA), Martinus Osendarp (OLA) 1932 Eddie Tolan (USA), Ralph Metcalfe (USA), Arthur Jonath (GER) 1928 Percy Williams (CAN), Jack London (GBR), Georg Lammers (GER) 1924 Harold Abrahams (GBR), Jackson Scholz (USA), Arthur -

Decathlon by K Ken Nakamura the Records to Look for in Tokyo: 1) by Winning a Medal, Both Warner and Mayer Become 14 Th Decathlete with Multiple Olympic Medals

2020 Olympic Games Statistics - Men’s Decathlon by K Ken Nakamura The records to look for in Tokyo: 1) By winning a medal, both Warner and Mayer become 14 th Decathlete with multiple Olympic medals. Warner or Mayer can become first CAN/FRA, respectively to win the Olympic Gold. 2) Can Maloney become first AUS to medal at the Olympic Games? Summary Page: All time Performance List at the Olympic Games Performance Performer Points Name Nat Pos Venue Yea r 1 1 8893 Roman Sebrle CZE 1 Athinai 2004 1 1 8893 Ashton Eaton USA 1 Rio de Janeiro 2016 3 8869 Ashton Eaton 1 London 2012 4 3 8834 Kevin Mayer FRA 2 Rio de Janeiro 2016 5 4 8824 Dan O’Brien USA 1 Atlanta 1996 6 5 8847/8798 Daley Thompson GBR 1 Los Angeles 1984 7 6 8820 Bryan Clay USA 2 Athinai 2004 Lowest winning score since 1976: 8488 by Christian Schenk (GDR) in 1988 Margin of Victory Difference Points Name Nat Venue Year Max 240 8791 Bryan Clay USA Beijing 2008 Min 35 8641 Erkki Nool EST Sydney 2000 Best Marks for Places in the Olympic Games Pos Points Name Nat Venue Year 1 8893 Roman Sebrle CZE Athinai 2004 Ashton Eaton USA Rio de Janeiro 2016 2 8834 Kevin Mayer FRA Rio de Janeiro 2016 8820 Bryan Clay USA Athinai 2004 3 8725 Dmitriy Karpov KAZ Athinai 2004 4 8644 Steve Fritz USA Atlanta 1996 Last eight Olympics: Year Gold Nat Time Silver Nat Time Bronze Nat Time 2016 Ashton Eaton USA 8893 Kevin Mayer FRA 8834 Damian Warner CAN 8666 2012 Ashton Eaton USA 8869 Trey Hardee USA 8671 Leonel Suarez CUB 8523 2008 Bryan Clay USA 8791 Andrey Kravcheko BLR 8551 Leonel Suarez CUB 8527 2004 Roman -

Cal Track & Field Weekly Schedule 2019 Schedule

CAL TRACK & FIELD EVENT DATES LOCATION WATCH LIVE LIVE STATS Bryan Clay/Mt. Sac/ April 17-20 Azusa/Torrance/ FloTrack Record Timing Beach/Cardinal Long Beach/Stanford 2019 SCHEDULE WEEKLY SCHEDULE DATE EVENT LOCATION BRYAN CLAY INVITATIONAL BEACH INVITATIONAL Jan. 25-26 UW Invitational Seattle Men (Decathlon) Friday Feb. 8-9 Husky Classic - Canceled Seattle Wednesday Women Feb. 15 Last Chance College Elite Seattle 100m: Tyler Brendel, Hakim McMorris Hammer: Camryn Rogers Long Jump: Tyler Brendel, Hakim McMorris Javelin: Chrissy Glasmann Feb. 22-23 MPSF Championship Seattle Shot Put: Tyler Brendel, Hakim McMorris Men MAR. 2 CAL OUTDOOR OPENER BERKELEY High Jump: Tyler Brendel, Hakim McMorris Hammer: Silviu Bocancea Mar. 8-9 NCAA Championship College Station 400m: Tyler Brendel, Hakim McMorris Saturday Mar. 15-16 Hornet Invitational/Open Sacramento Decathlon Day 1 Total: Tyler Brendel, Hakim Women Mar. 29-30 SF State Distance Carnival Hayward McMorris Discus: Kendall Mader, Emma DeSilva Mar. 29-30 Stanford Invitational Stanford Thursday Men April 6 The Big Meet Stanford 110m Hurdles: Tyler Brendel, Hakim McMorris Shot Put: Joshua Johnson, Malik McMorris, Iffy April 17-19 Bryan Clay Invitational Azusa Discus: Tyler Brendel, Hakim McMorris Joyner April 18-20 Mt. Sac Relays Torrance Pole Vault: Tyler Brendel, Hakim McMorris Discus: Joshua Johnson, Malik McMorris, Iffy Joyner Javelin: Tyler Brendel, Hakim McMorris April 19-20 Beach Invitational Long Beach 1500m: Tyler Brendel, Hakim McMorris April 19-20 Cardnial Classic Stanford Decathlon Total: Tyler Brendel, Hakim McMorris CARDINAL CLASSIC APRIL 26-27 BRUTUS HAMILTON BERKELEY Friday May 4 Sacramento Open Sacramento Women May 4-5 Pac-12 Combined Events Tucson MT. -

August Wilson and Pittsburgh's Hill District Betina Jones

Duquesne University Duquesne Scholarship Collection Electronic Theses and Dissertations 2011 "This Is Me Right Here": August Wilson and Pittsburgh's Hill District Betina Jones Follow this and additional works at: https://dsc.duq.edu/etd Recommended Citation Jones, B. (2011). "This Is Me Right Here": August Wilson and Pittsburgh's Hill District (Doctoral dissertation, Duquesne University). Retrieved from https://dsc.duq.edu/etd/709 This Immediate Access is brought to you for free and open access by Duquesne Scholarship Collection. It has been accepted for inclusion in Electronic Theses and Dissertations by an authorized administrator of Duquesne Scholarship Collection. For more information, please contact [email protected]. “THIS IS ME RIGHT HERE”: AUGUST WILSON AND PITTSBURGH‟S HILL DISTRICT A Dissertation Submitted to the McAnulty College and Graduate School of Liberal Arts Duquesne University In partial fulfillment of the requirements for the degree of Doctor of Philosophy By Betina Jones May 2011 Copyright by Betina Jones 2011 “THIS IS ME RIGHT HERE”: AUGUST WILSON AND PITTSBURGH‟S HILL DISTRICT By Betina Jones Approved March 29, 2011 ________________________________ ________________________________ Linda Kinnahan, Ph.D. Anne Brannen, Ph.D. Professor of English Associate Professor of English Dissertation Director (Committee Member) ________________________________ Magali Michael, Ph.D. Professor of English (Committee Member) ________________________________ ________________________________ Christopher M. Duncan, Ph.D. Magali Michael, Ph.D. Dean, McAnulty College and Graduate Chair, Department of English School of Liberal Arts Professor of English iii ABSTRACT “THIS IS ME RIGHT HERE”: AUGUST WILSON AND PITTSBURGH‟S HILL DISTRICT By Betina Jones May 2011 Dissertation supervised by Linda Kinnahan, Ph.D. -

African Americans and Baseball, 1900-1947

W&M ScholarWorks Dissertations, Theses, and Masters Projects Theses, Dissertations, & Master Projects 2006 "They opened the door too late": African Americans and baseball, 1900-1947 Sarah L. Trembanis College of William & Mary - Arts & Sciences Follow this and additional works at: https://scholarworks.wm.edu/etd Part of the African History Commons, American Studies Commons, Social and Behavioral Sciences Commons, and the United States History Commons Recommended Citation Trembanis, Sarah L., ""They opened the door too late": African Americans and baseball, 1900-1947" (2006). Dissertations, Theses, and Masters Projects. Paper 1539623506. https://dx.doi.org/doi:10.21220/s2-srkh-wb23 This Dissertation is brought to you for free and open access by the Theses, Dissertations, & Master Projects at W&M ScholarWorks. It has been accepted for inclusion in Dissertations, Theses, and Masters Projects by an authorized administrator of W&M ScholarWorks. For more information, please contact [email protected]. “THEY OPENED THE DOOR TOO LATE” African Americans and Baseball, 1900-1947 A Dissertation Presented to The Faculty of the Lyon Gardiner Tyler Department of History The College of William and Mary in Virginia In Partial Fulfillment Of the Requirements for the Degree of Doctor of Philosophy by Sarah Lorraine Trembanis 2006 Reproduced with permission of the copyright owner. Further reproduction prohibited without permission. APPROVAL SHEET This dissertation is submitted in partial fulfdlment of the requirements for the degree of Doctor of Philosophy Sarah Lorraine Trembanis Approved by the Committee, August 2006 Kimberley L. PhillinsJPh.D. and Chair Frederick Comey, Ph.D. Cindy Hahamovitch, Ph.D. Charles McGovern, Ph.D eisa Meyer, Ph.D. -

2018 Track & Field Record Book

2018 TRACK & FIELD RECORD BOOK CALIFORNIA GOLDEN BEARS 2019 TRACK & FIELD RECORD BOOK 1 2019 CALIFORNIA TRACK & FIELD 2018 SCHEDULE QUICK FACTS Date Day Meet Site Name ....................University of California January Location .............................Berkeley, Calif. 25-26 Fri.-Sat. at UW Invitational Seattle, Wash. Founded ........................................... 1868 February Enrollment ..................................... 40,173 8-9 Fri.-Sat. at Husky Classic Seattle, Wash. Nickname ............................Golden Bears 22-23 Fri.-Sat. at MPSF Indoor Championships Seattle, Wash. Colors ................Blue (282) & Gold (123) Chancellor .............................. Carol Christ March Director of Athletics ... ........ Jim Knowlton 2 Sat. California Outdoor Opener Berkeley, Calif. Senior Associate 8-9 Fri.-Sat. at NCAA Indoor Championships College Station, Texas Athletic Director ....................... Foti Mellis 15-16 Fri.-Sat. at Hornet Invitational Sacramento, Calif. Home Facility ............... Edwards Stadium 29 Fri.-Sat at SFSU Distance Carnival Hayward, Calif. (22,000) 29-30 Fri.-Sat at Stanford Invitational Stanford, Calif. 2018 Men’s Finishes (indoor): April MPSF/NCAA ...........................8th/20th 6 Sat. The Big Meet Stanford, Calif. 2018 Men’s Finishes (outdoor): 17-18 Wed.-Thu. Mt. Sac Relays & California Combined Events Azusa, Calif. Pac-12/NCAA .......................... 6th/NTS 19-20 Fri.-Sat. Cardinal Team Classic Palo Alto, Calif. 2018 Women’s Finishes (indoor): 26-27 Fri.-Sat. Brutus Hamilton Challenge Berkeley, Calif. MPSF/NCAA ............................ 4th/NTS 2018 Women’s Finishes (outdoor): May Pac-12/NCAA .......................... 8th/NTS 4 Sat. at Sacramento State Open Sacramento, Calif. 4-5 Sat.-Sun. at Pac-12 Multi-Event Championships Tuscon, Ariz.. ATHLETIC COMMUNICATIONS 11-12 Sat.-Sun. at Pac-12 Outdoor Championships Tuscon, Ariz.. Assistant Director Athletic Communica- 23-25 Thu.-Sat. -

06 Track & Field Gd P27-68.Pmd

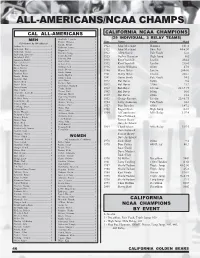

ALL-AMERICANS/NCAA CHAMPS CAL ALL-AMERICANS CALIFORNIA NCAA CHAMPIONS (29 INDIVIDUAL, 3 RELAY TEAMS) MEN Ozolinsh, Lenards ................................ 1 Phelps, Clarence ................................... 1 Year Name Event Mark (159 honors by 106 athletes) Porath, David ....................................... 1 Adkins, Lee .......................................... 1 1922 John Merchant Hammer 161-4 Robinson, James ................................... 1 Anderson, Don ..................................... 3 Rogers, Jeff ............................................ 1 1922 John Merchant Shot Put 44-6.50 Anderson, George ................................ 2 Roseme, George .................................... 1 1922 Allen Norris Pole Vault 12-6 Anderson, Lawrence ............................ 1 Scannella, Jim ....................................... 1 Archibald, Dave ................................... 3 1925 Oather Hampton High Jump 6-2 Schmidt, Don ........................................ 1 Asmerom, Bolota .................................. 1 Shafer, Mike .......................................... 1 1930 Ken Churchill Javelin 204-2 Barnes, Clarence ................................... 1 Siebert, Jerry ......................................... 1 1932 Ken Churchill Javelin 215-0 Beaty, Forrest ....................................... 5 Simpson, Len ........................................ 1 Biles, Martin ......................................... 2 1936 Archie Williams 400m 47.0 Smith, Devone ...................................... 1 Biles, Robert