FERMENTING STRUGGLES Pulque, Mezcal, and Tequila

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Leaf Unfolding Rates for Pulque Agaves

Leaf Unfolding Rates and Responses to Cuticle Damaging for Pulque Agaves in Mexico Item Type Article Authors García-Moya, Edmundo; Nobel, Park S. Publisher University of Arizona (Tucson, AZ) Journal Desert Plants Rights Copyright © Arizona Board of Regents. The University of Arizona. Download date 26/09/2021 00:58:02 Link to Item http://hdl.handle.net/10150/609137 García -Moya and Nobel Agave Cuticle 55 Introduction Leaf Unfolding Rates Approximately 100 species of Agave occur natively or are cultivated in Mexico (Gentry, 1982). Fiber is obtained from the leaves of Agave lechuguilla in northern Mexico and and Responses to from A. fourcroydes in the Yucatán peninsula and southern Tamaulipas. Following fermentation of the stem, distilled Cuticle Damaging beverages are produced, such as tequila from A. tequilana in Jalisco and mezcal from about ten species in various states. for Pulque Agaves The fermented beverage pulque is produced from the exudate that collects in hollowed -out stems of mature plants of A. mapisaga and A. salmiana in the Valley of Mexico. The in Mexico unfermented exudate (known as aguamiel, or "honey water ") is also consumed on a limited scale (Gentry, 1982; Nobel, 1988). Aguamiel and pulque production probably dates back at least 2500 years. Certainly pulque production was well Edmundo García -Moya established by the twelfth century (Martin del Campo, 1938; Goncalves de Lima, 1956). In the past, the cuticle (plus some de Postgraduados, Mexico Colegio Chapingo, underlying epidermis) has been removed from the leaves of pulque agaves for use as paper. Currently such cuticles are Park S. Nobel used to wrap and hence flavor meat in a liquid -tight sack University of California, Los Angeles, California containing other ingredients for steam cooking (termed "mixiote," a food especially common at Christmas; Po- loniato, 1986). -

“To Avoid This Mixture”: Rethinking Pulque in Colonial Mexico City Daniel Nemsera a University of California, Berkeley, California, USA

This article was downloaded by: [University of California, Berkeley] On: 23 February 2011 Access details: Access Details: [subscription number 929586225] Publisher Routledge Informa Ltd Registered in England and Wales Registered Number: 1072954 Registered office: Mortimer House, 37- 41 Mortimer Street, London W1T 3JH, UK Food and Foodways Publication details, including instructions for authors and subscription information: http://www.informaworld.com/smpp/title~content=t713642611 “To Avoid This Mixture”: Rethinking Pulque in Colonial Mexico City Daniel Nemsera a University of California, Berkeley, California, USA Online publication date: 23 February 2011 To cite this Article Nemser, Daniel(2011) '“To Avoid This Mixture”: Rethinking Pulque in Colonial Mexico City', Food and Foodways, 19: 1, 98 — 121 To link to this Article: DOI: 10.1080/07409710.2011.544204 URL: http://dx.doi.org/10.1080/07409710.2011.544204 PLEASE SCROLL DOWN FOR ARTICLE Full terms and conditions of use: http://www.informaworld.com/terms-and-conditions-of-access.pdf This article may be used for research, teaching and private study purposes. Any substantial or systematic reproduction, re-distribution, re-selling, loan or sub-licensing, systematic supply or distribution in any form to anyone is expressly forbidden. The publisher does not give any warranty express or implied or make any representation that the contents will be complete or accurate or up to date. The accuracy of any instructions, formulae and drug doses should be independently verified with primary sources. The publisher shall not be liable for any loss, actions, claims, proceedings, demand or costs or damages whatsoever or howsoever caused arising directly or indirectly in connection with or arising out of the use of this material. -

The Early Path, from the Sacred to the Profane in Fermented Beverages in New Galicia, New Spain (Mexico), Seventeenth to Eighteenth Century

The Early Path, from the Sacred to the Profane in Fermented Beverages in New Galicia, New Spain (Mexico), Seventeenth to Eighteenth Century María de la Paz SOLANO PÉREZ The Beginning of the Path: Introduction From an Ethno-historical perspective, the objectives of the present paper are to show changes in perceptions of fermented beverages, as they lost their sacral nature in a good part of the baroque society of New Spain’s Viceroyalty,1 turn- ing into little more than profane beverages in the eye of the law of the Spanish crown for the new American territories, specifically for the Kingdom of New Galicia during the seventeenth and eighteenth centuries, within the New Spain viceroyalty. At the time the newly profane beverages were discredited in urban places, were subject to displacement by distilled beverages, being introduced from both oceans – from the Atlantic by the way of the Metropolis, and from the Pacific through the Manilla Galleon. The new distilled beverages converged in western New Spain, where Guadalajara was the economic, political, religious, and cultural centre. To begin with, it is necessary to stress that the fermentation process has been used for many purposes since ancient times. Most notably, it has been used in medicine, in nutrition, and as part of religion and rituality for most societies around the world. 1 This area, after its independence process in the beginning of the nineteenth century, was known as Mexico. Before this date, it belonged to the Spanish Crown as New Spain, also as part of other territories situated along the American continent. -

Agave Beverage

● ALCOHOLIC BEVERAGES Agave salmiana Waiting for the sunrise ‘Tequila to wake the living; mezcal to wake the dead’ - old Mexican proverb. Before corn was ever domesticated, agaves (Agave spp.) identifi ed it with a similar plant found at home. Agaves fl ower only once (‘mono- were one of the main carbohydrate sources for humans carpic’), usually after they are between in what is today western and northern Mexico and south- 8-10 years old, and the plant will then die if allowed to set seed. This trait gives western US. Agaves (or magueyes) are perennial, short- rise to their alternative name of ‘century stemmed, monocotyledonous succulents, with a fl eshy leaf plants’. Archaeological evidence indicates base and stem. that agave stems and leaf bases (the ‘heads’, or ‘cores’) and fl owering stems By Ian Hornsey and ’ixcaloa’ (to cook). The name applies have been pit-cooked for eating in Mes- to at least 100 Mexican liquors that oamerica since at least 9,000 BC. When hey belong to the family Agavaceae, have been distilled with alembics or they arrived, the Spaniards noted that Twhich is endemic to America and Asian-type stills. Alcoholic drinks from native peoples produced ‘agave wine’ whose centre of diversity is Mexico. agaves can be divided into two groups, although their writings do not make it Nearly 200 spp. have been described, according to treatment of the plant: ’cut clear whether this referred to ‘ferment- 150 of them from Mexico, and around bud-tip drinks’ and ’baked plant core ed’ or ‘distilled’ beverages. This is partly 75 are used in that country for human drinks’. -

Bacterial Diversity and Population Dynamics During the Fermentation Of

bioRxiv preprint doi: https://doi.org/10.1101/480038; this version posted November 29, 2018. The copyright holder for this preprint (which was not certified by peer review) is the author/funder, who has granted bioRxiv a license to display the preprint in perpetuity. It is made available under aCC-BY-ND 4.0 International license. 1 Bacterial diversity and population dynamics during the 2 fermentation of palm wine from Guerrero Mexico 3 Fernando Astudillo-Melgar1,3, Adrián Ochoa-Leyva2, José Utrilla3* Gerardo Huerta- 4 Beristain1* 5 6 1.- Laboratorio de Investigación en Biotecnología, Universidad Autónoma de Guerrero, 7 Chilpancingo, México. 8 2.- Departamento de Microbiología Molecular, Instituto de Biotecnología- Universidad 9 Nacional Autónoma de México, Cuernavaca, México. 10 3.- Programa de Biología de Sistemas y Biología Sintética, Centro de Ciencias Genómicas - 11 Universidad Nacional Autónoma de México, Cuernavaca, México. 12 13 *Co-corresponding authors 14 José Utrilla 15 [email protected] 16 17 Gerardo Huerta-Beristain 18 [email protected] 19 1 bioRxiv preprint doi: https://doi.org/10.1101/480038; this version posted November 29, 2018. The copyright holder for this preprint (which was not certified by peer review) is the author/funder, who has granted bioRxiv a license to display the preprint in perpetuity. It is made available under aCC-BY-ND 4.0 International license. 20 Abstract 21 Palm wine is obtained by fermentation of palm tree sap. In the Pacific coast of Mexico, 22 palm wine is called Tuba and it is consumed as a traditional fermented beverage. Tuba has 23 empirical applications such as an auxiliary in gastrointestinal diseases and a good source of 24 nutrients. -

The Bilimek Pulque Vessel (From in His Argument for the Tentative Date of 1 Ozomatli, Seler (1902-1923:2:923) Called Atten- Nicholson and Quiñones Keber 1983:No

CHAPTER 9 The BilimekPulqueVessel:Starlore, Calendrics,andCosmologyof LatePostclassicCentralMexico The Bilimek Vessel of the Museum für Völkerkunde in Vienna is a tour de force of Aztec lapidary art (Figure 1). Carved in dark-green phyllite, the vessel is covered with complex iconographic scenes. Eduard Seler (1902, 1902-1923:2:913-952) was the first to interpret its a function and iconographic significance, noting that the imagery concerns the beverage pulque, or octli, the fermented juice of the maguey. In his pioneering analysis, Seler discussed many of the more esoteric aspects of the cult of pulque in ancient highland Mexico. In this study, I address the significance of pulque in Aztec mythology, cosmology, and calendrics and note that the Bilimek Vessel is a powerful period-ending statement pertaining to star gods of the night sky, cosmic battle, and the completion of the Aztec 52-year cycle. The Iconography of the Bilimek Vessel The most prominent element on the Bilimek Vessel is the large head projecting from the side of the vase (Figure 2a). Noting the bone jaw and fringe of malinalli grass hair, Seler (1902-1923:2:916) suggested that the head represents the day sign Malinalli, which for the b Aztec frequently appears as a skeletal head with malinalli hair (Figure 2b). However, because the head is not accompanied by the numeral coefficient required for a completetonalpohualli Figure 2. Comparison of face date, Seler rejected the Malinalli identification. Based on the appearance of the date 8 Flint on front of Bilimek Vessel with Aztec Malinalli sign: (a) face on on the vessel rim, Seler suggested that the face is the day sign Ozomatli, with an inferred Bilimek Vessel, note malinalli tonalpohualli reference to the trecena 1 Ozomatli (1902-1923:2:922-923). -

EVERYTHING ABOUT PULQUE AGAVOLOGY 'Water from the Green Plants…'

EVERYTHING ABOUT PULQUE AGAVOLOGY 'Water from the green plants…' Tequila's predecessor, pulque, or octli, was made from as many as six types of agave grown in the Mexican highlands. Pulque is one of about thirty different alcoholic beverages made from agave in Mexico - many of which are still made regionally, although seldom available commercially. The drink has remained essential to diet in the central highlands of Mexico since pre-Aztec times. Pulque is like beer - it has a low alcoTeqhol content, about 4-8%, but also contains vegetable proteins, carbohydrates and vitamins, so it also acts as a nutritional supplement in many communities. Unlike tequila or mezcal, the agave sap is not cooked prior to fermentation for pulque. Pulque, is an alcoholic spirit obtained by the fermentation of the sweetened sap of several species of 'pulqueros magueyes' (pulque agaves), also known as Maguey Agaves. It is a traditional native beverage of Mesoamerica. Though it is commonly believed to be a beer, the main carbohydrate is a complex form of fructose rather than starch. The word 'pulque' comes from the Náhuatl Indian root word poliuhqui, meaning 'disturbed'. There are about twenty species of agave and several varieties of pulque. Of these there was one that was called "metlaloctli" ie "blue pulque," for its colouration. Plant Sources of Pulque The maguey plant is not a cactus (as has sometimes been mistakenly suggested) but an Agave, believed to be the Giant Agave (Agave salmiana subspecies salmiana). The plant was one of the most sacred plants in Mexico and had a prominent place in mythology, religious rituals, and Mesoamerican industry. -

Pulque, a Traditional Mexican Alcoholic Fermented Beverage: Historical, Microbiological, and Technical Aspects

REVIEW published: 30 June 2016 doi: 10.3389/fmicb.2016.01026 Pulque, a Traditional Mexican Alcoholic Fermented Beverage: Historical, Microbiological, and Technical Aspects Adelfo Escalante 1*, David R. López Soto 1, Judith E. Velázquez Gutiérrez 2, Martha Giles-Gómez 3, Francisco Bolívar 1 and Agustín López-Munguía 1 1 Departamento de Ingeniería Celular y Biocatálisis, Instituto de Biotecnología, Universidad Nacional Autónoma de México, Cuernavaca, Mexico, 2 Departamento de Biología, Facultad de Química, Universidad Nacional Autónoma de México, Ciudad Universitaria, Ciudad de México, Mexico, 3 Vagabundo Cultural, Atitalaquia, Mexico Pulque is a traditional Mexican alcoholic beverage produced from the fermentation of the fresh sap known as aguamiel (mead) extracted from several species of Agave (maguey) plants that grow in the Central Mexico plateau. Currently, pulque is produced, sold and consumed in popular districts of Mexico City and rural areas. The fermented product is a milky white, viscous, and slightly acidic liquid beverage with an alcohol content between 4 and 7◦ GL and history of consumption that dates back to pre-Hispanic times. In this contribution, we review the traditional pulque production Edited by: process, including the microbiota involved in the biochemical changes that take place Jyoti Prakash Tamang, Sikkim University, India during aguamiel fermentation. We discuss the historical relevance and the benefits of Reviewed by: pulque consumption, its chemical and nutritional properties, including the health benefits Matthias Sipiczki, associated with diverse lactic acid bacteria with probiotic potential isolated from the University of Debrecen, Hungary Giulia Tabanelli, beverage. Finally, we describe the actual status of pulque production as well as the social, Università di Bologna, Italy scientific and technological challenges faced to preserve and improve the production of *Correspondence: this ancestral beverage and Mexican cultural heritage. -

COCTELES Maximón Margarita 16 Patrón Single Barrel Reposado, Patrón Citronge, Agave, Lime, Salt

COCTELES Maximón Margarita 16 patrón single barrel reposado, patrón citronge, agave, lime, salt The margarita (Spanish for “daisy”) is a variation on a popular American drink, the Daisy, remade with tequila instead of brandy. Tequila rose in popularity during Prohibition as people traveled over the border in search of spirits. The first mention of the drink was in 1936 in an Iowa newspaper article by James Graham, who found the drink in Tijuana. classic smokey spicy Colibri 14 wheatley vodka, passion fruit, coconut, orange, lemongrass Papel Picado 14 charanda uruapan, plantation pineapple rum, raspberry, cinnamon, lime Amor Confinado 15 cimarron reposado tequila, cachaca, tomatillo, golden berry, epazote Monchito 16 ilegal mezcal, green chartreuse, coconut, pineapple, lime Xibalba 16 bozal tobasiche mezcal, sherry, amaro, chocolate, hoja santa Gin & Tonic 16 Baltimore Spirits Company Shot Tower | USA fever tree elderflower tonic, lemon, juniper, violet Príncipe de Los Apóstoles | Argentina fever tree aromatic tonic, grapefruit, pink peppercorn, huacatay Xoriguer Mahón | Spain fever tree mediterranean tonic, lemon, thyme SPIRIT-FREE Agua Fresca 12 choice of pineapple, hibiscus, or tamarind, lime, piloncillo, soda BY THE GLASS CHAMPAGNE & SPARKLING WINE Bodega Norton, 101 Bubbles, Grüner NV 11 mendoza, argentina Ramon Canals-Canals, Cava Rosé Reserva 2016 12 penedes, spain Veuve Clicquot Brut NV 25 champagne, france WHITE WINE Scarbolo, Pinot Grigio 2018 13 friuli-venezia, italy Max Ferdinand Richter 13 Riesling Mülheimer Sonnenlay Zeppelin -

Bar Menu • Spring 2018 Cocktails Milagros Specialties Served Individually | Pitcher of 3 | Pitcher of 6 El Perro Loco | Espolon Reposado Tequila | St

bar menu • spring 2018 cocktails milagros specialties served individually | pitcher of 3 | pitcher of 6 el perro loco | espolon reposado tequila | st. germain elderflower liquer cold pressed ruby red grapefruit & lime juices | combier 14 strawberry fields | altos reposado tequila strawberry & basil house syrup | cold pressed lime juice | fever tree gingerbeer 11 no way rose | hangar one rose vodka | grapefruit & lemon juice | st. germain elderflower liquer topped with chandon sparkling rose 10 red wine sangria | apple | pineapple | lemon oranges float of spanish brandy 9 | pitcher of four 32 watermelon margarita | altos blanco tequila fresh watermelon | cold pressed citrus juices 12 |pitcher of 3 34 | pitcher of 6 66 el jefe | don julio’s 70th year anniversary anejo tequila,cold-pressed citrus juices | organic agave nectar 13 / 37 / 72 capella | espolon reposado tequila | grand marnier cold pressed lime, orange & ruby red grapefruit juices 12 / 34 / 66 mexican hipster | jalapeno infused el jimador blanco muddled cucumber | cold pressed lime juice organic agave nectar splash of soda 12 / 34 / 66 fire engine| order one for $8 everytime a fire engine rolls by! sauza “blue” 100% blue agave tequila cold-pressed citrus juices agave nectar | red wine sangria 10 / 28 / 54 watermelon mule | ketel one vodka | fresh watermelon | cold pressed lime juice | fever tree ginger beer 11 cocktails milagros specialties served individually | pitcher of 3 | pitcher of 6 milagros margarita | herradura blanco tequila cold-pressed citrus juices | organic agave -

Activity of Zymomonas Species in Palm- Sap Obtained

JASEM ISSN 1119-8362 Full-text Available Online at J. Appl. Sci. Environ. Mgt. 2005 All rights reserved http:// www.bioline.org.br/ja Vol. 9 (1) 25 - 30 Activity of Zymomonas species in palm-sap obtained from three areas in Edo State, Nigeria. OBIRE, O. Department of Applied and Environmental Biology, Rivers State University of Science and Technology, Nkpolu-Oroworukwo, P.M.B. 5080, Port Harcourt. ABSTRACT: The bacterium Zymomonas mobilis was isolated from fresh palm-sap samples from three different locations as to determine the contribution of the bacterial isolate to alcohol production in palm-wine. Carbohydrate (sugar) fermentation, alcohol tolerance, and growth of the bacterium at different pH and temperature values were determined; and a comparison of sugar fermentation by Z. mobilis and Saccharomyces cerevisiae was also determined. Z. mobilis contributes much to the fermentation of palm-wine due to its ability to ferment sucrose, glucose and fructose which are the main sugars in palm-sap. The bacterium reached its maximum density of 2.72 x 107 cells/ml between 12 and 15 hrs after tapping of the palm-sap. Z. mobilis is acid and alcohol tolerant being able to grow at pH values between 4.0 and 7.0 and in alcohol concentration of between 2.5% and 15% respectively. Z. mobilis was also found to ferment sugars at a faster rate than Saccharomyces cerevisiae. Statistical analysis of the data obtained using ANOVA showed that there is no significant difference at p = 0.05 level of significance in the growth of isolates of Z. mobilis obtained from the three locations under different pH, alcohol and temperature values. -

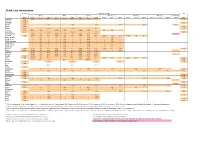

Drink Size Information Generic Beverage Specific GF Beer Wine Spirits Other A* A1 & * A2 Other B* B Other C * C Combined Grams Size (L) Vol

Drink size information Generic Beverage specific GF Beer Wine Spirits Other A* A1 & * A2 Other B* B Other C * C Combined grams size (l) vol. (%) grams size (l) vol. (%) grams size (l) vol. (%) grams size (l) vol. (%) grams size (l) vol. (%) grams size (ll) vol. (%) grams grams grams Argentina 12.0 0.350 5.0 12.6*1 0.125 12.8 13.9*1 0.04 40.0 12.7*1 12.0 Australia 10.0 Australia 2 10.0 10.0 Austria 20.0 - - 20.0 - - 20.0 - - 20.0 - - 20.0 - - 20.0 20.0 Belize 10.0 10.0 Brazil 12.0 - - 12.0 - - 12.0 - - 12.0 12.0 Canada 13.6 0.341 5.0 1 0.150 12.0 1 0.004 40.0 1 0.3 5.0 1 Costa Rica 12.0 - - 12.0 - - 12.0 - - 12.0 12.0 Czech Republic 0.500 5.0 19.8*1 0.200 12.0 19*1 0.050 40.0 15.9*1 18*8 Denmark 12.0 0.330 5.0 13.1*1 0.120 12.0 11.4*1 0.040 38.0 12.1*1 0.080 19.0 12.1*1 0.330 5.0 13.1*1 ECAS: Finland *4 5.0 *2 *4 11.5 *2 *4 38.0 *2 *4 5.0 *2 ECAS: France *4 5.0 *2 *4 12.0 *2 *4 38.0 *2 *4 5.0 *2 ECAS: Germany *4 4.9 *2 *4 11.0 *2 *4 38.0 *2 *4 5.0 *2 ECAS: Italy *4 4.6 *2 *4 11.0 *2 *4 38.0 *2 *4 - *2 ECAS: Sweden *4 5.2 *2 *4 11.5 *2 *4 38.0 *2 *4 3.3 *2 ECAS: UK *4 4.1 *2 *4 11.5 *2 *4 38.0 *2 *4 4.2 *2 Finland 10.0 0.330 4.6 12.1*1 0.100 12.3 9.7*1 0.040 36.4 11.6*1 0.330 4.7 12.4*1 10.0 France 10.9*6 0.250 5.0 9.9*1 0.150 12.0 14.3*1 0.040 42.5 13.5*1 - - 10.9*6 *2 Germany 0.265 4.8 10.1*1 0.225 11.0 19.7*1 0.020 33.0 5.3*1 Hungary 0.500 5.0 19.8*1 0.100 11.5 9.1*1 0.050 40.0 15.9*1 *2 Iceland 13.0 0.330 5.0 13.1*1 0.125 12.5 12.4*1 0.050 38.0 15.1*1 India 10.0 0.330 5.0 13.1*1 - - 10.0 *5 0.030 42.8 10.2*1 0.033 33.3 8.8*1 0.030 42.8