Brecon Beacons Warrens

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Residential Allocations Settlement Site Code Site Name Brecon B15

Residential Allocations Settlement Site Code Site Name Brecon B15 Cwmfalldau Fields (Under construction) CS28 Cwmfalldau fields extension CS93 Slwch House Field CS132 UDP allocation B17 opposite High School, North of Hospital (Mixed Use site of which 4.55ha is allocated for housing) DBR-BR-A Site located to the North of Camden Crescent and to the East of the Breconshire War Memorial Hospital DBR-BR-B Site located to the north of Cradoc Close and west of Maen-du Well Crickhowell DBR-CR-A Land above Televillage Hay-on-Wye DBR-HOW-A Land opposite The Meadows DBR-HOW-C Land adjacent to Fire Station DBR-HOW-K Land adjacent to Caemawr Cottages CS136 UDP allocation H6 Former Health Centre Sennybridge & Defynnog SALT 002/092 Land at Castle Farm CS138 Glannau Senni Talgarth T9 UDP allocation Land North of Doctors Surgery CS137 Hay Road (Mixed Use site of which 0.75ha is allocated for housing) Bwlch DBR-BCH-J Land adjacent to Bwlch Woods Crai CS43 Land SW of Gwalia CS42 Land at Crai Gilwern CS102 Lancaster Drive (Former UDP allocation GW2) Govilon CS39/69/70/ Land at Ty Clyd 88/89/99 Libanus DBR-LIB-E Land adjacent Pen y Fan Close Llanbedr DBR-LBD-A Land adjacent to St Peter’s Close Llanfihangel DBR-LC-D Land opposite Pen-y-Dre Farm Crucorney Llanigon DBR-LGN-D Land opposite Llanigon County Primary School Llanspyddid DBR-LPD-A Land off Heol St Cattwg Pencelli CS120 Land south of Ty Melys Pennorth DBR-PNT-D Land adjacent to Ambelside Ponsticill CS91 Land to the West of Pontsicill House, Pontsticill CS55 Land adjacent to Penygarn DBR-PSTC-C Land at end of Dan-y-Coed CS139 UDP allocation PST1 adj. -

Ystradfellte Community Council

Cyngor Cymuned Ystradfellte Community Council Clerk: Mrs Susan Harvey Powell Llwynfedwen Farm, Hepste, Penderyn, Aberdare, CF44 9QA Tel: 01685 813201 [email protected] Dear Sir/Madam You are summoned to attend the ordinary meeting of the Ystradfellte Community Council to be held at Pontneddfechan Village Hall on Monday 4th March 2019 at 7.00 p.m. to transact the following business. Dated this day 26th February 2019 1. Apologies 2. To confirm minutes of the ordinary meeting of the Community Council held on the 4th February 2019 3. Dyfed Powys Police 4. County Borough Council Matters 5. Matters Arising 6. Correspondence 7. Planning Applications 8. Accounts 9. Members Verbal Reports Yours sincerely Susan Harvey Powell Clerk To The Chairman and all members of Ystradfellte Community Council 1 Ystradfellte Community Council Minutes of the meeting of Ystradfellte Community Council held at Ystradfellte Church Hall on 4th February 2019 at 7.00 p.m. Present: Cllrs. C Woodley, H Pattrick, D Thomas, L Jones,K Bowman, L Cornish, P.C.S.O. N Watkins Apologies: G Reynolds 2019/11 Minutes The minutes were passed as a true record proposed by Cllr. Bowman and seconded by Cllr. Woodley 2019/12 Declaration of Interest None recorded 2019/13 Dyfed Powys Police P.C.S.O. Watkins reported that a suspicious vehicle was seen near Carn Crochon farm. A foreign gentleman sat in a van thee for about 2 hours on 25th January 2019. Some vehicles were damaged in Bro Dawel. Also recycling was not collected in Bro Dawel due to cars obstructing the route. -

A TIME for May/June 2016

EDITOR'S LETTER EST. 1987 A TIME FOR May/June 2016 Publisher Sketty Publications Address exploration 16 Coed Saeson Crescent Sketty Swansea SA2 9DG Phone 01792 299612 49 General Enquiries [email protected] SWANSEA FESTIVAL OF TRANSPORT Advertising John Hughes Conveniently taking place on Father’s Day, Sun 19 June, the Swansea Festival [email protected] of Transport returns for its 23rd year. There’ll be around 500 exhibits in and around Swansea City Centre with motorcycles, vintage, modified and film cars, Editor Holly Hughes buses, trucks and tractors on display! [email protected] Listings Editor & Accounts JODIE PRENGER Susan Hughes BBC’s I’d Do Anything winner, Jodie Prenger, heads to Swansea to perform the role [email protected] of Emma in Tell Me on a Sunday. Kay Smythe chats with the bubbly Jodie to find [email protected] out what the audience can expect from the show and to get some insider info into Design Jodie’s life off stage. Waters Creative www.waters-creative.co.uk SCAMPER HOLIDAYS Print Stephens & George Print Group This is THE ultimate luxury glamping experience. Sleep under the stars in boutique accommodation located on Gower with to-die-for views. JULY/AUGUST 2016 EDITION With the option to stay in everything from tiki cabins to shepherd’s huts, and Listings: Thurs 19 May timber tents to static camper vans, it’ll be an unforgettable experience. View a Digital Edition www.visitswanseabay.com/downloads SPRING BANK HOLIDAY If you’re stuck for ideas of how to spend Spring Bank Holiday, Mon 30 May, then check out our round-up of fun events taking place across the city. -

Brecknock Rare Plant Register Species of Interest That Are Not Native Or Archaeophyte S8/1

Brecknock Rare Plant Register Species of interest that are not native or archaeophyte S8/1 S8/1 Acanthus mollis 270m Status Local Welsh Red Data GB Red Data S42 National Sites Bear's-breech Troed yr arth Neophyte LR 1 Jun 2013 Acanthus mollis SO2112 Blackrock Mons: Llanelly: SSSI0733, SAC08 DB⁴ S8/2 Acer platanoides 260m Status Local Welsh Red Data GB Red Data S42 National Sites Norway Maple Masarnen Norwy 70m Neophyte NLS 18 Nov 2020 Acer platanoides SO0207 Nant Ffrwd, Merthyr Tydfil MT: Vaynor IR¹⁰ Oct 2020 Acer platanoides SO0012 Llwyn Onn (Mid) MT: Vaynor IR⁵ Apr 2020Acer platanoides SN9152 Celsau CFA11: Treflys JC¹ Mar 2020 Acer platanoides SO2314 Llanelly Mons: Llanelly JC¹ Feb 2019Acer platanoides SN9758 Cwm Crogau CFA11: Llanafanfawr DB¹ Oct 2018 Acer platanoides SO0924 Castle Farm CFA12: Talybont-On-Usk DB¹ Jan 2018 Acer platanoides SN9208 Afon Mellte CFA15: Ystradfellte: SSSI0451, DB⁴ SAC71, IPA139 Apr 2017Acer platanoides SN9665 Wernnewydd CFA09: Llanwrthwl DB¹ Jul 2016 Acer platanoides SO0627 Usk CFA12: Llanfrynach DB¹ Jun 2015Acer platanoides SN8411 Coelbren CFA15: Tawe-Uchaf DB² Sep 2014Acer platanoides SO1937 Tregoyd Villa field CFA13: Gwernyfed DB¹ Jan 2014 Acer platanoides SO2316 Cwrt y Gollen site CFA14: Grwyney… DB¹ Apr 2012 Acer platanoides SO0528 Brecon CFA12: Brecon DB¹⁷ 2008 Acer platanoides SO1223 Llansantffraed CFA12: Talybont-On-Usk DB² May 2002Acer platanoides SO1940 Below Little Ffordd-fawr CFA13: Llanigon DB² Apr 2002Acer platanoides SO2142 Hay on Wye CFA13: Llanigon DB² Jul 2000 Acer platanoides SO2821 Pont -

Hydrogeology of Wales

Hydrogeology of Wales N S Robins and J Davies Contributors D A Jones, Natural Resources Wales and G Farr, British Geological Survey This report was compiled from articles published in Earthwise on 11 February 2016 http://earthwise.bgs.ac.uk/index.php/Category:Hydrogeology_of_Wales BRITISH GEOLOGICAL SURVEY The National Grid and other Ordnance Survey data © Crown Copyright and database rights 2015. Hydrogeology of Wales Ordnance Survey Licence No. 100021290 EUL. N S Robins and J Davies Bibliographical reference Contributors ROBINS N S, DAVIES, J. 2015. D A Jones, Natural Rsources Wales and Hydrogeology of Wales. British G Farr, British Geological Survey Geological Survey Copyright in materials derived from the British Geological Survey’s work is owned by the Natural Environment Research Council (NERC) and/or the authority that commissioned the work. You may not copy or adapt this publication without first obtaining permission. Contact the BGS Intellectual Property Rights Section, British Geological Survey, Keyworth, e-mail [email protected]. You may quote extracts of a reasonable length without prior permission, provided a full acknowledgement is given of the source of the extract. Maps and diagrams in this book use topography based on Ordnance Survey mapping. Cover photo: Llandberis Slate Quarry, P802416 © NERC 2015. All rights reserved KEYWORTH, NOTTINGHAM BRITISH GEOLOGICAL SURVEY 2015 BRITISH GEOLOGICAL SURVEY The full range of our publications is available from BGS British Geological Survey offices shops at Nottingham, Edinburgh, London and Cardiff (Welsh publications only) see contact details below or BGS Central Enquiries Desk shop online at www.geologyshop.com Tel 0115 936 3143 Fax 0115 936 3276 email [email protected] The London Information Office also maintains a reference collection of BGS publications, including Environmental Science Centre, Keyworth, maps, for consultation. -

Königreichs Zur Abgrenzung Der Der Kommission in Übereinstimmung

19 . 5 . 75 Amtsblatt der Europäischen Gemeinschaften Nr . L 128/23 1 RICHTLINIE DES RATES vom 28 . April 1975 betreffend das Gemeinschaftsverzeichnis der benachteiligten landwirtschaftlichen Gebiete im Sinne der Richtlinie 75/268/EWG (Vereinigtes Königreich ) (75/276/EWG ) DER RAT DER EUROPAISCHEN 1973 nach Abzug der direkten Beihilfen, der hill GEMEINSCHAFTEN — production grants). gestützt auf den Vertrag zur Gründung der Euro Als Merkmal für die in Artikel 3 Absatz 4 Buch päischen Wirtschaftsgemeinschaft, stabe c ) der Richtlinie 75/268/EWG genannte ge ringe Bevölkerungsdichte wird eine Bevölkerungs gestützt auf die Richtlinie 75/268/EWG des Rates ziffer von höchstens 36 Einwohnern je km2 zugrunde vom 28 . April 1975 über die Landwirtschaft in Berg gelegt ( nationaler Mittelwert 228 , Mittelwert in der gebieten und in bestimmten benachteiligten Gebie Gemeinschaft 168 Einwohner je km2 ). Der Mindest ten (*), insbesondere auf Artikel 2 Absatz 2, anteil der landwirtschaftlichen Erwerbspersonen an der gesamten Erwerbsbevölkerung beträgt 19 % auf Vorschlag der Kommission, ( nationaler Mittelwert 3,08 % , Mittelwert in der Gemeinschaft 9,58 % ). nach Stellungnahme des Europäischen Parlaments , Eigenart und Niveau der vorstehend genannten nach Stellungnahme des Wirtschafts- und Sozialaus Merkmale, die von der Regierung des Vereinigten schusses (2 ), Königreichs zur Abgrenzung der der Kommission mitgeteilten Gebiete herangezogen wurden, ent sprechen den Merkmalen der in Artikel 3 Absatz 4 in Erwägung nachstehender Gründe : der Richtlinie -

NEWSLETTER Welsh Mills Society

Cymdeithas Melinau Cymru NEWSLETTER Welsh Mills Society HYDREF/OCTOBER 2019 RHIF/NO 137 Blackpool Mill, Pembrokeshire (John Crompton) Welsh Mills Society Cymdeithas Melinau Cymru NEWSLETTER 137 OCTOBER 2019 Contents: Editorial 3 News from the mills 9 Cover Story 4 Mills for Sale 10 Dates for your Diary 4 Post Mills in Wales 14 Membership News 5 A farm wheel 19 Congratulations 6 Book Review 22 Mucky Mills Group 6 Twenty-five Years Ago 18 The Welsh Mills Society was launched in 1984. The aims of the Society are to study, record, interpret and publicise the wind and water mills of Wales, to encourage general interest, and to advise on their preservation and use. Officers and Committee Officers: Chairman: Gerallt Nash [email protected] Secretary: Hilary Malaws [email protected] Treasurer: Tim Haines [email protected] Membership Secretary: Brian Malaws [email protected] Journal Editor: Mel Walters [email protected] (and at Coed Trewernau Mill, Crossgates, LLandindrod Wells, Powys, LD1 6PG) Committee: Gareth Beech [email protected] John Crompton (Mucky Mills) [email protected] Andrew Findon (Mill Owners’ Forum) 01974 251231 [email protected] Emma Hall [email protected] Anne Parry (Publicity and website) [email protected] Jane Roberts (Bring & Buy stall) 01633 780247 Helen Williams [email protected] Contact details show the preferred addresses of Committee members. For further information, please write to the Hon. Secretary: Hilary Malaws, Y Felin, Tynygraig, Ystrad Meurig, Ceredigion, Wales SY25 6AE or visit our web site at: www.welshmills.org 2 EDITORIAL Your editor approaches this page with mixed feelings, for this is the last time he will have the freedom to address the membership without restraint. -

Review of Community Boundaries in the County of Powys

LOCAL GOVERNMENT BOUNDARY COMMISSION FOR WALES REVIEW OF COMMUNITY BOUNDARIES IN THE COUNTY OF POWYS REPORT AND PROPOSALS LOCAL GOVERNMENT BOUNDARY COMMISSION FOR WALES REVIEW OF COMMUNITY BOUNDARIES IN THE COUNTY OF POWYS REPORT AND PROPOSALS 1. INTRODUCTION 2. POWYS COUNTY COUNCIL’S PROPOSALS 3. THE COMMISSION’S CONSIDERATION 4. PROCEDURE 5. PROPOSALS 6. CONSEQUENTIAL ARRANGEMENTS 7. RESPONSES TO THIS REPORT The Local Government Boundary Commission For Wales Caradog House 1-6 St Andrews Place CARDIFF CF10 3BE Tel Number: (029) 20395031 Fax Number: (029) 20395250 E-mail: [email protected] www.lgbc-wales.gov.uk Andrew Davies AM Minister for Social Justice and Public Service Delivery Welsh Assembly Government REVIEW OF COMMUNITY BOUNDARIES IN THE COUNTY OF POWYS REPORT AND PROPOSALS 1. INTRODUCTION 1.1 Powys County Council have conducted a review of the community boundaries and community electoral arrangements under Sections 55(2) and 57 (4) of the Local Government Act 1972 as amended by the Local Government (Wales) Act 1994 (the Act). In accordance with Section 55(2) of the Act Powys County Council submitted a report to the Commission detailing their proposals for changes to a number of community boundaries in their area (Appendix A). 1.2 We have considered Powys County Council’s report in accordance with Section 55(3) of the Act and submit the following report on the Council’s recommendations. 2. POWYS COUNTY COUNCIL’S PROPOSALS 2.1 Powys County Council’s proposals were submitted to the Commission on 7 November 2006 (Appendix A). The Commission have not received any representations about the proposals. -

City Centr Walking Tr

Image Credits and Copyrights National Waterfront Museum p7, Glynn Vivian Art Gallery p10: Powell Dobson Architects. The Council of the City & County of Swansea cannot guarantee the accuracy of the information in this brochure and accepts no responsibility for any error or misrepresentation, liability for loss, disappointment, negligence or other damage caused by the reliance on the information contained in this brochure unless caused by the negligent act or omission of the Council. This publication is available in alternative formats. Contact Swansea Tourist Information Centre (01792 468321. Published by the City & County of Swansea © Copyright 2014 Welcome to Swansea Bay, Mumbles and Gower City Centre Swansea, Wales’ Waterfront City, has a vibrant City Centre with over 230 shops and Wales’ largest Walking Trail indoor market. As well as a wide range of indoor attractions (including the oldest and newest museums in Wales), Swansea boasts award winning parks and gardens. Clyne Gardens is internationally famous for its superb collection of rhododendrons and Singleton Botanical Gardens is home to spectacular herbaceous borders and large glasshouses. Swansea sits on the sandy 5 mile stretch of Swansea Bay beach, which leads to the cosy but cosmopolitan corner of Mumbles. Capture its colourful charm from the promenade and pier, the bistros and boutiques, and the cafés and medieval castle. Mumbles marks the beginning of the Gower Peninsula’s coastline. Explore Gower’s 39 miles of captivating coastline and countryside. Ramble atop rugged limestone cliffs, uncover a cluster of castles or simply wander at the water’s edge - a breathtaking backdrop is a given. Your adventure starts here! This guide takes you on a walking tour of the ‘Top 10’ most asked about attractions in and near Swansea City Centre, by visitors to Swansea Tourist Information Centre. -

Clear Streams Swansea (2013/14) Project Report and Evaluation

Clear Streams Swansea (2013/14) Project Report and Evaluation Contents Executive Summary 1. Introductory Information 1.1 Purpose and Scope of this Report 4 1.2 The Clear Streams Concept 4 1.3 Dŵr Cymru WFD Project Funding 5 1.4 Project Funding Applications 5 2. Project Report 2.1 Project Aims 6 2.2 Organisation and Resources 7 2.3 Project Activities 10 2.3.1 Engaging Local Businesses 10 2.3.2 Engaging Householders and Communities 12 2.3.3 Engaging Partners 20 2.4 Publicity and Marketing 21 3. Project Evaluation 3.1 Online Survey 23 3.2 Delivery of Outcomes and Objectives 25 3.3 Project Governance 27 3.4 Lessons Learnt and Recommendations 28 This report has been prepared by PMDevelopments Executive Summary The Clear Streams Swansea project was an eighteen-month collaboration between Swansea Environmental Forum, the Wildlife Trust of South and West Wales and Natural Resources Wales. The project, funded by the Dŵr Cymru WFD Project Funding scheme, aimed to raise awareness of the water environment and improve water quality in the Swansea area. The project was part of, and built upon, a wider initiative developed by Environment Agency Wales, working in partnership with others to employ a holistic approach to managing water quality. Two new officer posts were created to deliver the project and these were supported by a steering group comprising representatives of the three partner organisations. The Dŵr Cymru WFD Project Funding scheme provided £100,000 to the project with an additional £30,000 contributed by Environment Agency Wales (replaced by Natural Resources Wales). -

Ystradfellte Community Council

1 Cyngor Cymuned Glyn Tarell Community Council Minutes of the meeting of Glyn Tarell Community Council held at Libanus Chapel on 15th February 2016 at 7.30 p.m. Present: Cllrs. P Cravos, R Tiernan, M Smith, L Fitzpatrick Apologies: Cllr. M Keylock, P Hill 2016/12 Minutes The minutes of 15the February 2016 were passed as a true record proposed by Cllr. Smith and seconded by Cllr. Tiernan 2016/13 Declaration of Interest None recorded 2016/14 County Borough Council a. Flooding in Llanspyddid – meeting with Simon Crowther and colleagues on 29th February2016 b. Llanspyddid bus shelter – no update c. Llanspyddid Church – nothing to report. d. Cllr. Fitzpatrick reported that the budget is slightly better as 1.2 million extra has been received. 2016/15 Matters Arising a. Libanus playground – this project was mainly funded by grants from Awards for All, Powys CC and BBNP 2016/16 Defibrillators Grants are not available until the new financial year. 2 2016/17 Libanus Church The Church has still not been put up for sale. There is an action plan and Cllr. Smith reported that it will be publicised to the wider community for the residents’ vision of the project. One Voice Wales will be approached regarding a Public Works loan. 2016/18 Baddegai Trust Letters have been sent to the residents involved. No update from the trustees 2016/19 Correspondence a. Talgarth Male Voice Choir - letter asking for financial assistance 2016/20 Planning a. Parc Beddw, LIbanus, side extension – noted b. Old Coach House, Glanrhyd Libanus, construction of outbuilding for agricultural purposes - noted 2016/21 Accounts Payments Website £33.60 One Voice Wales £77.00 Wages and Tax £125.00 Account Balances Treasurers Account £9740.01 Business Bank Instant £84.92 2016/22 Members Verbal Reports a. -

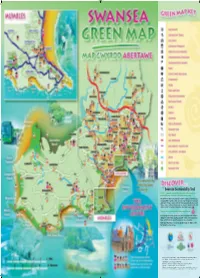

Swansea Sustainability Trail a Trail of Community Projects That Demonstrate Different Aspects of Sustainability in Practical, Interesting and Inspiring Ways

Swansea Sustainability Trail A Trail of community projects that demonstrate different aspects of sustainability in practical, interesting and inspiring ways. The On The Trail Guide contains details of all the locations on the Trail, but is also packed full of useful, realistic and easy steps to help you become more sustainable. Pick up a copy or download it from www.sustainableswansea.net There is also a curriculum based guide for schools to show how visits and activities on the Trail can be an invaluable educational resource. Trail sites are shown on the Green Map using this icon: Special group visits can be organised and supported by Sustainable Swansea staff, and for a limited time, funding is available to help cover transport costs. Please call 01792 480200 or visit the website for more information. Watch out for Trail Blazers; fun and educational activities for children, on the Trail during the school holidays. Reproduced from the Ordnance Survey Digital Map with the permission of the Controller of H.M.S.O. Crown Copyright - City & County of Swansea • Dinas a Sir Abertawe - Licence No. 100023509. 16855-07 CG Designed at Designprint 01792 544200 To receive this information in an alternative format, please contact 01792 480200 Green Map Icons © Modern World Design 1996-2005. All rights reserved. Disclaimer Swansea Environmental Forum makes makes no warranties, expressed or implied, regarding errors or omissions and assumes no legal liability or responsibility related to the use of the information on this map. Energy 21 The Pines Country Club - Treboeth 22 Tir John Civic Amenity Site - St. Thomas 1 Energy Efficiency Advice Centre -13 Craddock Street, Swansea.